The six preparatory practices

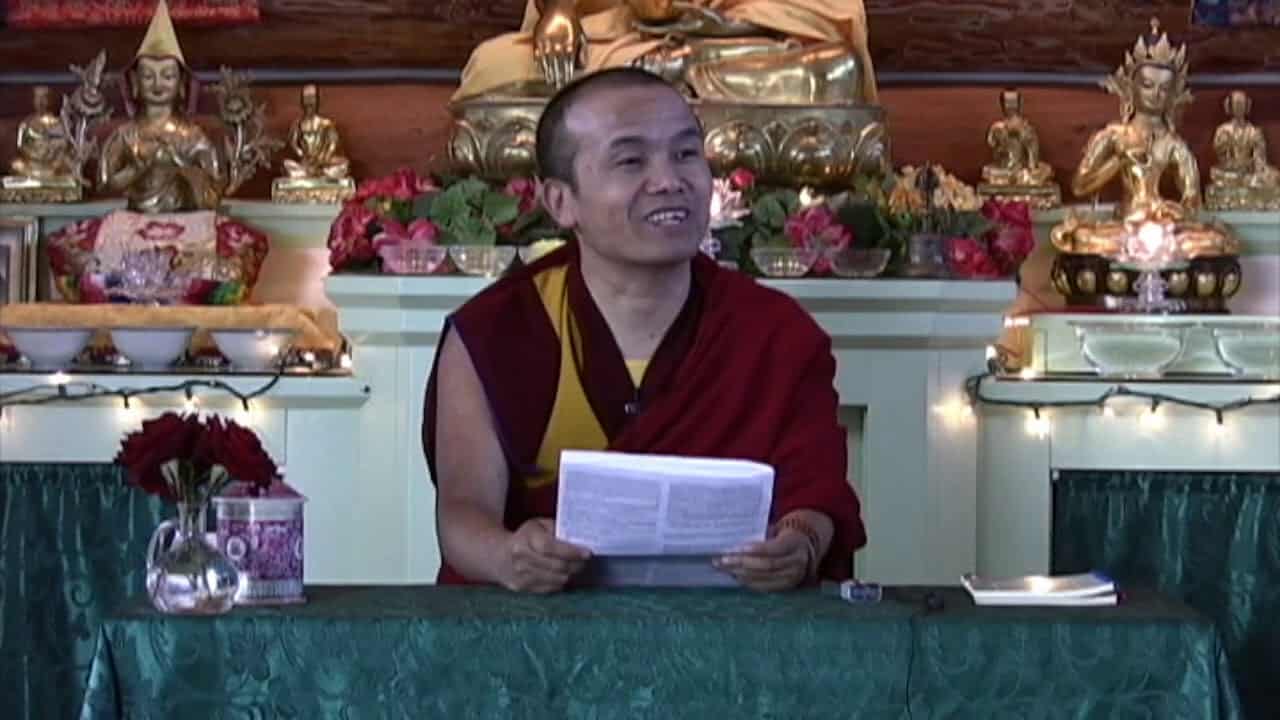

A series of commentaries on Mind Training Like Rays of the Sun by Nam-kha Pel, a disciple of Lama Tsongkhapa, given between September 2008 and July 2010. This talk is from September 25, 2008.

- Cleaning the room and setting up the shrine

- Obtaining offerings

- The eight-point posture and establishing a good motivation

- Visualize the field of positive potential

- The seven-limb prayer and mandala

- Requesting inspiration

MTRS 04: The six preparatory practices (download)

Motivation

Let’s take a moment and cultivate our motivation. Since last week when we heard the teachings, we’ve had the great fortune to live another week. Our life could have so easily been interrupted, but it wasn’t. So let’s rejoice that we have this opportunity again to listen to the teachings. But let’s also be aware that death could come at any time and, therefore, we don’t have any time to waste because our life is very meaningful and has a lot of purpose because we can use it to create the causes to die well and have a good rebirth, to create the causes for liberation and full enlightenment. So let’s really make a strong determination to do just that and to apply ourselves to learning, reflecting upon, and meditating on the Buddha’s teachings for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Training in the preliminaries

We’ve been contemplating Mind Training Like Rays of the Sun and we’re on page 19. If you don’t have the book, don’t worry about it because I’m reading it, so you can listen to it while I’m reading. We’re starting the actual teachings which begin with the first phrase that says:

First, train in the preliminaries.

It doesn’t say, “First, go to the highest, most complicated, exotic practice with the longest name and the best advertisement.” That’s not what it says. It says, “First, train in the preliminaries.” The first paragraph here says:

This involves contemplating the significance and rarity of life as a free and fortunate human being, [that’s the first preliminary, and]1 contemplating impermanence and death, which leads to the realization that our life can end at any time2 [that’s the second preliminary], and thinking about the causes and results of actions [that is the third preliminary] and the vicious nature of cyclic existence.

And that is the fourth preliminary. So the four are: precious human life, impermanence and death, karma and its effects and the disadvantages of cyclic existence. Those are sometimes called the four things that turn the mind to the Dharma.

From these basic practices up to the training in the ultimate awakening mind [that means the wisdom realizing emptiness], the practice can be divided into two: the actual meditation session and the period between sessions. [Practice includes everything: our formal meditation and the break times.] The actual session is divided into three—preparation, meditation and dedication.3

Firstly, as the life-story of guru Dharmamati of Sumatra shows [guru Dharmamati is Serlingpa, so it’s not Dharmarakshita who was the author of “Wheel of Sharp Weapons.” They’re two different people. According to his life story], we should decorate the place, arrange representations of the Three Jewels (the Buddha, the Fully Awakened Being, his Doctrine and the Spiritual Community), offer a mandala (representing the world system) and complete the six kinds of conduct up to the request that the three great purposes (of self, others and both) shall be fulfilled.

This talks about the six preparatory practices, so I will explain this right now.

The six preparatory practices

First preparatory practice

First, we sweep and clean the room. I know some of you don’t like that so much. You’ve got to put all your dirty tea cups in the sink and clean them. You’ve got to make your bed and things like this, but actually, it has a very good effect on your mind if you keep your room very tidy and clean, because how you keep your environment reflects how you keep your mind. So you clean the environment also thinking, according to the thought training practice, that you’re sweeping or vacuuming up the defilements of sentient beings. So that’s the first of the six preliminaries.

The other part of the first preliminary is to set up the altar. By the way, altar is spelled a-l-t-a-r. So many people write to me and say, “How do I set up an a-l-t-e-r?” Alter as in alter ego, but it’s a-l-t-a-r, okay? Altar is a shrine, okay? So how do you set one up? Usually, in the highest place we put a picture of our spiritual mentor because the spiritual mentor is the one who connects us to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Just below that we have an image of the Buddha that represents the Buddha’s form—the Buddha’s body. On the Buddha’s right, or on our left as we look at it, there is a text and that represents the Buddha’s speech, so it’s good to have one of the prajnaparamita texts, if you can. On the Buddha’s left, or our right as we look at the altar, is a representation of the Buddha’s mind, and that could be a bell or it could be a stupa. A stupa is one of those monuments that are made—you often see the big ones that people circumambulate here. You just put a small one on your altar. You can also have pictures of Chenrezig and Manjushri and any other deities that you incorporate into your practice, all around the altar. It’s very neat and tidy and I always have my altar higher. If it’s in my bedroom, I put it higher than where my bed is because I don’t want to be looking down at the Buddha when I sleep. The Buddha should be higher than me. Similarly, if you’re seated on the floor, the Buddha’s higher up. If you’re seated on a chair, then you raise the Buddha higher still. So that’s setting up the altar.

Second preparatory practice

Then the second preparatory practice is to make offerings. We can offer anything that we consider beautiful. The purpose of offering is to create joy and delight in being generous and in giving, to free ourselves from miserliness and to create a lot of merit because the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha are very powerful objects because of their spiritual realizations, so we create very strong karma with them. If we make offerings to them, it’s quite potent karma, so there’s a practice of offering seven water bowls. If we do that, then we have seven bowls that are clean and we wipe out each one with a cloth and put it upside down. We never leave empty bowls right-side up on the altar, so you wipe it and put it upside down. The cloth is the wisdom realizing emptiness and any dust on the inside of the bowl represents the defilements of sentient beings. So you’re cleansing sentient beings’ minds with the wisdom realizing emptiness. You should wipe each bowl and put one on top of the other, upside down. Then you put them in your hand and you put some water in the top bowl. It doesn’t need to be totally full; just some water. Then you pick up the top bowl and you pour all the water except for a little bit into the second bowl. You put that one down on the Buddha’s right, or on your left as you’re facing the altar. Then you pick up the next one and you pour everything out except a little bit and you put that one second, leaving them about a rice grain’s distance apart. I never understood whether it was long-grained rice or short-grained rice, so please excuse me. Then you take the third one and you pour all the water but a little bit and put that one down, and you go on like this until the end of the row. It’s very important to place the offering bowls in a straight line with just that short distance between them. You don’t want them to be too close because that’s like being too close and getting burnt. You don’t want them to be too distant either, like being separated from your teachers. So place them just the right distance apart. When each bowl has a little bit of water then you’re saying, “Om Ah Hum” as you’re putting it down because those three syllables consecrate it. Then go back to the first bowl and fill it up, again within a rice grain’s distance from the top. You don’t make it completely full so that the water is slightly above and it’s about ready to spill, because you want your offerings to be neat. This is very much a practice in taking care and being respectful so you don’t want to fill your bowl so full that there’s water all over the place, and yet you don’t want to leave them so empty as if you’re being miserly and not offering very much. So you offer each one in turn, filling it up almost to the top, but not quite. And again say, “Om Ah Hum” to consecrate it. Imagine as you’re filling it that you’re offering the Buddha wisdom nectar. The water is like wisdom nectar. Or you can imagine while you’re pouring it that you’re filling sentient beings up with this very blissful wisdom nectar.

You can also offer candles, or maybe better yet are electric lights because then there’s no danger of fire. And really, don’t take this lightly because one Dharma center I lived in, in France, had a whole wing burn down because somebody left a candle on their altar burning when they left the room. This is why at the Abbey we don’t allow burning candles and lit incense in people’s rooms; it’s just too dangerous. So you can offer candles and incense and you can put some food up there and flowers. Flowers represent offering virtue and they also represent offering impermanence because the flowers are so beautiful and then they fade and you have to throw them out. So it’s like our body; you’re young you’re beautiful and then the body just gets decrepit. You can offer light—that represents wisdom and it creates the karma to receive wisdom. Offering incense represents ethical conduct because they say that people who keep very pure ethical conduct have a very fragrant smell around them. If you offer food that represents samadhi because people who have very deep samadhi are nourished by their meditative concentration; they don’t need to eat as much. You can offer music. At some of our pujas we ring bells and we play drums and that represents, again, impermanence or emptiness. So you make all these offerings and you say, “Om Ah Hum” with each one to consecrate it as you’re offering to the Buddha. You do this in the morning and it’s a very nice practice to do when you first get up. Even if you’re half asleep, it’s a very good habit to get yourself into because you’re making offerings and you’re thinking of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

And then at the end of the day, you can take the offerings down. So with the water you start at the Buddha’s left, on your right, and you take that one and empty it into a pitcher. And then if they’re the kind of bowls that dry without spotting then you don’t need to wipe them. You can wipe it if you want to, but it’s not necessary. So you pour the water out and then you turn the bowl upside down. Then you take the next one, pour it into the pitcher and turn it upside down. You can stack the bowls, or leave one leaning on the next if you want to. When you’re taking the water down, you can recite the Vajrasattva mantra and think that you are purifying sentient beings by pouring away their afflictions and negative karma while reciting Vajrasattva. You do this with all of the bowls and then, put the leftover water in some flowers or some plants, or throw it outside where nobody walks. Don’t flush it down the toilet or throw it down the drain so it mixes in with all the other dirty things. Try to put it in some clean place. The food—it doesn’t say this in the scriptures, but I think it’s very helpful to request the Buddha’s permission to take the food. Otherwise, I’ve noticed so many people who offer food to the Buddha just happen to take it off the altar when it’s their lunch time or dessert time. Then I wonder if they really offered it. They said, “Om Ah Hum,” but did they really offer it, or were they just putting it on the altar until they wanted it? So that’s why I think it’s good to ask the Buddha’s permission, as a caretaker of the Buddha’s possessions, to take the food. Then we can either eat it ourselves or give it to friends. Flowers should be thrown outside some place where they can decompose. Then you put your altar to sleep in that way at the end of the day.

It’s a very nice way to frame your day. Offerings can really be quite nice. When you’re making each offering, don’t just think, “Oh, I’m offering a small bowl of water to the Buddha,” but think that it’s transforming into so much blissful wisdom nectar and that there’s these beautiful offerings just filling the sky. You’re not just offering one flower but a whole sky full of beautiful flowers. And you’re not just offering one apple, but the whole sky is full of apples—organic ones, because you don’t want the Buddha to have to eat pesticides. So you can imagine that things are very pure and that the apples don’t have cores and things like that. You imagine very nice things to offer and when you’re making the actual offerings, it’s good to offer the best quality that we have. Don’t go to the grocery store, buy a whole bunch of fruit, and put the ones that got bruised on the altar and keep the good ones for yourself. It shouldn’t be like that. We put the nice ones on the altar and then we eat the ones that are going bad. The mind feels so happy when we can make very beautiful offerings. There’s something so wonderful about visualizing beauty, and especially things that you think are just gorgeous. Visualize the whole sky full of them and offer them. It’s very nice and it really makes the mind quite happy.

If you’re attached to something when you’re making offerings, imagine millions of those. I don’t know how many zillions of computers the Buddha gets from all the people who like all the widgets, the technological widgets, and they’re always looking through the magazines thinking, “Oh what’s the latest thing that’s come out?” And then, “Okay I’ve got to restrain my attachment, I really don’t need this.” So as a practice to cut off your attachment to it, you offer beautiful iPods and stupendous computers and fantastic color printers that actually work, and all sorts of beautiful things filling the sky, to the Buddha. You imagine that the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas accept them with much pleasure. So that’s the meaning of actual offerings. There are offerings that you put on the altar and then there are the mentally transformed ones, or the ones that you imagined.

Third preparatory practice

The third of the six preparatory practices is to sit in a comfortable position and examine your mind. So you stop and you think, “Okay, is my mind peaceful or is my mind in a hurry and flurry? Or is my mind falling asleep? What’s going on?” If your mind is kind of distracted and you’re still thinking of the day’s activities, then do some breathing meditation. Do just 21 breaths or some short meditation like that and let your mind calm down. Some people like to do longer breathing meditation. I was suggesting 21 if you’re going on to do some of the lamrim analytic meditations. But if you need more time to do more breathing meditation to stabilize your mind, please take the time and do that because you want your mind to be calm and peaceful before you start the analytic meditations.

Also, as part of the third step, you generate a good motivation and you really reflect on, “Why am I meditating?” Sometimes when you sit there and think, “Why am I meditating?” It’s just like, “well, this is what I do at 5:30 every morning.” That’s the only motivation you have: “Everybody else in the community is doing it, I just got up with them.” So you should stop and see what your real motivation is and then cultivate the aspiration for full enlightenment for the benefit of all beings.

Now when it says, “sit in a comfortable position,” as part of the third one, this refers to the seven-fold position of Vairochana. It’s eight-fold if you include the breathing meditation, but I already covered that. The recommended position is to sit in the full vajra position, which means that your right foot is on your left thigh and your left foot is on your right thigh. Some people call that the lotus but it’s actually called the vajra position. If you can sit like that, great. If you can’t, then try the half vajra, with one leg down and the other one up. If that doesn’t work so well, then sit like Tara sits with your left leg tucked in and your right leg in front and both of your legs flat on the floor. If that doesn’t work, sit cross-legged. If that doesn’t work, then try a meditation bench—you know, those small benches with the back tilted. You tuck your legs under the bench and then you sit on the little bench. If that doesn’t work then sit in a chair. When you sit in a chair, sit in a straight-backed chair with your feet flat on the floor. Don’t sit in a nice comfortable lounge chair because you know what happens if you do that. So however you’re seated, keep your back straight because that helps the circulation of the subtle airs, or the winds, in your body.

[Venerable Thubten Chodron demonstrates various postures and positioning of limbs in the following sections.]

Then your hands are the right on the left palms up, like this, with your thumbs touching to form a triangle. So your thumbs aren’t slouching; they’re up like this and that’s right in your lap. Your hands are in your lap touching your body right at the level of your abdomen—your stomach’s up here, your abdomen is lower. And then your hands just rest naturally, and when they do, then there’s a little space between your body and your arms. So when your hands are in your lap, don’t make yourself so tight that your arms become like chicken wings, like they’re stuck out, and don’t make them so flat like you’re sitting here like this, but just in a normal way.

And then your shoulders are level. What I found can be very helpful if you have pain in your back, is to lift your shoulders real high like this, tuck your neck in and then drop your shoulders really hard and then just kind of wiggle your neck a little bit. I find that very helpful if there’s tension in the shoulders. So, high … touching it … lift it really high, I mean as high as you can get them. And then, let them go. And then, just kind of tuck your neck in. I find that very helpful if you have tension back here.

Then, your face is level, or if anything, the chin is just slightly tucked in. If your chin gets too low, that’s what happens, or, if you raise your chin higher, like some people who have bifocals, I’ve noticed that when you look at them, they’re always looking at you like this. And it took me a long time to realize, they’re not looking down on me, they’re just trying to focus. But you don’t want your head to be like this because then your neck’s going to get sore so, you just want it level, like this.

And then your mouth is closed and you breathe through your nose, unless you have allergies or a cold, and then breathe any way you can. I say this being someone who frequently gets colds and has allergies. I remember so many retreats teaching breathing meditation and I can’t breathe. So if you can’t breathe through your nose, just breathe through your mouth. Just breathe, okay. So presuming you can do it through your nose, then keep your mouth shut. They say to put your tongue on your palate; I’m not sure where else your tongue would go. When I close my mouth my tongue’s on my palate. Do you have any place else your tongue can go? Do you have a space between your tongue and the palate?

Audience: I think people have funny habits sometimes….

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Oh, okay, so maybe people have funny habits….

So just try and keep your mouth closed and your tongue inside in there. Then, your eyes are lowered but they’re not really looking at anything. They say to rest them on the tip of your nose. I have a big nose so that’s fairly easy, but it doesn’t always feel comfortable so I think just down in front of you is quite fine. That lets some light in. That way you don’t get sleepy or tired. If you really have problems getting sleepy or tired, take a little bowl of water—not a big cup—a little bowl, and you balance it on your head when you meditate. It usually only takes falling asleep once when you’re in a room full of people and the bowl falls—usually after that you don’t fall asleep so much. There are certain positive attributes to being embarrassed.

If you’re a monastic and you have a dingwa, a seating cloth, it’s very helpful when we sit down to think—because our dingwa has four corners and it’s right over our seat,—my attention is not going beyond the scope of this dingwa. In other words, it’s not going to the computer. It’s not going to fixing breakfast. It’s not going to what I did 20 years ago or what I have to do tomorrow. It’s staying right here within these four corners of my seating cloth. I found that very helpful. So you’re sitting there and you’re not looking at what your neighbor’s doing. If you’re in a room full of people, you’re not thinking about, “Gee, that person is moving or making too much noise with their mala.” Or, “Gee, why are they breathing so loud?” Or, “How come they’re taking off their velcro jacket in the middle of a silent meditation?” You just have your attention right there on yourself and on what’s happening with you. So that’s the third preparatory.

The fourth one says visualize the merit field with the gurus, Buddhas and bodhisattvas and then we take refuge. Oh, I’m sorry, taking refuge came in the third step. Let’s go back to the third step. Rewind. So for the third step, sit quietly and comfortably, do the breathing meditation, set your motivation and then take refuge and generate bodhicitta. When we take refuge we usually have the refuge visualization, so, it’s quite detailed. There’s one big throne with five smaller thrones on it. And the Buddha sits on the front throne. Your actual teachers sit on the throne in front of the Buddha. The one on the Buddha’s right is where Maitreya and the other lamas from the extensive lineage sit. The throne on the Buddha’s left is where Manjushri and the other lineage lamas from the profound lineage sit. In the back you have other spiritual mentors; Shantideva and those of the ear-whispered lineage, and so on. And then around, still on the big throne but around the five smaller thrones, you have the meditational deities, the Buddhas, the bodhisattvas, the solitary realizers, the hearers, the dakas, dakinis and the Dharma protectors. These are the arya Dharma protectors, not the mundane Dharma protectors.

So they are all on this one throne and this is the refuge visualization, not to be confused with the field of merit. You have the same figures but in the merit field, which is in step four, they’re seated on the top of a tree that’s in an ocean with a lotus on top and then they’re all seated on the petals of the lotus. Some of the lamas are seated in the space and Je Tsongkhapa is the center figure there. That’s the one we have in our meditation hall, the field of merit. But here, this is the refuge visualization.

By the way, don’t expect yourself to see every single Buddha. When you go into a room, you don’t notice every single person. You get the general feeling that there’s a lot of people in there. Just have the feeling that you’re in the presence of all of these. You can focus in on different ones from time to time. It’s good to make your visualization as clear as you can but don’t get discouraged if you can’t, or if everybody’s not appearing completely clearly all at once. If that’s too complicated then just visualize the Buddha. He has a throne, and then a lotus, and then a moon and sun disc. And the Buddha’s seated on top of that. And then think of the Buddha as the embodiment of all the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. That can be easier. And again, at the beginning your eyes are lowered and you’re generating a mental image of the Buddha. Don’t expect to see the Buddha with your eyes or something like that when you’re visualizing.

I remember one time in Mexico, I went to a Montessori school with these little kids to give them a little Dharma talk and introduce them to Buddhist things. So, we were going to sit down to meditate and the kids are saying how to meditate. And one little girl raises up her hand and says, “Well I do.” Then she sits and she goes (Ven. Chodron imitates child here). And I watched and sometimes adults do that too. You sit to meditate and (Ven. Chodron demonstrates) and you’re not very relaxed. Or maybe your mouth isn’t closed, but somehow you’re narrowing your focus so your brows knit somehow. Check if you have the habit of doing that. I won’t mention who does here. Then just really try and be aware of relaxing your facial muscles so you’re not squeezing to see the Buddha. You’re just letting the image of the Buddha appear to you.

If you have a hard time visualizing the Buddha then spend more time during the day looking at your altar and looking at the Buddha, because it’s the same mechanism. If I say, think of your best friend, an image comes to your mind very easily. If say, think of your mother, the image comes to your mind very easily. Even if you haven’t seen your mother in a long time, or even if she’s passed away. But that all happens because of familiarity. It’s the same thing if we start looking at the Buddha images around us or around our home and we sit down to meditate, we can visualize the Buddha easily. So visualize the Buddha in front so you can do the more elaborate visualization, and then you think that your mother’s on your left, your father’s on the right. It doesn’t matter whether they’re living or not. All the people that you don’t like are right there in front of you, between you and the refuge field and they’re looking at the refuge field so they’re not looking towards you giving you a dirty look; they’re looking towards the Buddha. But you’ve got to look at them to see the Buddha; you can’t escape. And then all around you are all the other sentient beings.

Then we think that we are leading all of the sentient beings in taking refuge and in generating bodhicitta. So at that point we can stop and do a little meditation on refuge and on bodhicitta and then say the prayer, “I take refuge until I am enlightened.” That prayer that we always do. So you either do it like that or you immediately call up that feeling of refuge and think of the good qualities of the Buddha and say the prayer. And you imagine that everybody else is saying it and taking refuge and generating bodhicitta together with you. And then you also do the four immeasurables at that point. You can do the long version of the four immeasurables or the short version. It’s nice some days to just do everything very quickly. Some days you stop and just contemplate each of the four in a very strong way.

There’s something I find quite nice about the way we do our practices in the Tibetan tradition; that there’s no fixed speed to how fast or slow or what melody you use when you do the different recitations. You can say them very fast, which sometimes is good because it makes your mind concentrate, or you can say them very slow which gives you more time to think about them while you’re saying them. You can say them and then pause and really meditate on each thing. You can change it from day to day as you do your practice. Don’t think that every day has to be the same, okay. Be a little bit creative here. Maybe we’re done with the third step. Actually, after you do that then the refuge visualization, all the figures in the refuge field dissolve into the Buddha. And the Buddha comes on top of your head and dissolves into you and goes into your heart.

Fourth preparatory practice

Step four is to visualize the merit field with the gurus, Buddhas and bodhisattvas. That’s the thangka with the tree that I described. Do we have a photograph of the thangka on our website? Or on thubtenchodron.org? Yes, with photographs. I think they must be somewhere on one of the websites, but you have the ocean and then the trees coming out of it. At the top of the tree there’s a lotus where the layers of the petals go down over the side of the tree. And then you have Je Tsongkhapa in the center and then Manjushri on his left in the sky in the lineage. The profound Maitreya on his right with the lineage of the extended, and so on. All the different figures around like that. Again, if that’s too complicated, then you just think of the Buddha in the space in front, if you want. And think of the Buddha as the embodiment of all the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

If you want, you can make it a Guru Yoga practice when you visualize the Buddha, or in this case you would visualize Lama Tsongkhapa and the Buddha at his heart, and Vajradhara at the Buddha’s heart. Then you can think that your spiritual mentor and the Buddha are the same nature. And actually all of your spiritual mentors and the Buddha are the same nature. So you can think of it as your spiritual mentor appearing in the form of the Buddha or in the form of Je Rinpoche. It’s important when you do this—when you try to make this a Guru Yoga practice—that you’re not thinking of the personality of your teacher. I think this is the big mistake we often make because we like the personality of our teacher. But when our teacher dies, then we feel lost because that personality isn’t there anymore. Actually, we should be trying to look beyond the superficial personality of our teacher and really think, “What is their mind?” And since this is a practice where we are seeing them as the same nature as the Buddha, then it becomes a practice of reflecting on, “what is the Buddha’s mind like,” and then seeing those two as separate. The purpose of doing that is then when we listen to teachings, we listen to the teachings better. Because if we listen to teachings and then we think, “Oh, here is my spiritual mentor who is the same nature as the Buddha teaching me,” then we think, “Oh, they’re telling me the same thing the Buddha would tell me.” So then we listen closely if we think, “Oh yes, here’s somebody who’s like the Buddha, who’s telling me.” Whereas if we think of our spiritual mentor as just kind of Joe Blow who doesn’t know much and picks their nose, burps, makes mistakes, contradicts themselves and whatever, you know. They tell you to put milk in their tea and then they tell you, don’t put milk in their tea, or they change their mind a lot and they change the schedule a lot. Or, they talk when it’s silent time. So, if you get really into picking at the faults of your teacher, then you’ll never find any end to the faults because the mind is very creative and will think of many many faults. But that isn’t very beneficial for us. We’re trying to look beyond that because if we look at our teachers, here’s this person who’s just like “Nah,” you know. Then when they teach, we’re going to think, “Can I really trust what they’re saying? And do they really mean this? And do they really care about me? And do they know what they’re talking about?” And all this doubt comes into our mind. And that kind of doubt is not very helpful, so it’s not that we want to listen to our teacher and just go, “Hallelujah, I believe.” No, that’s not it either. We should have a critical mind and be intelligent and think about the teachings and examine them, and contemplate them, but, if we’re seeing our teacher as the representative of the Buddha, the illumination of the Buddha, or something like that, then we listen more closely and then we think, “Oh, these teachings are for me.” If you go to His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s teachings, there’s what, 5,000 people, sometimes half a million people there. In India, there are just huge numbers of people there and then you think, “Oh, well he’s just teaching this, it’s not for me.” So His Holiness talks about being patient and kind and you think, “Oh yes, he’s talking about those other people in the audience but he’s not talking to me.” We shouldn’t think like this. When we’re in teachings, whether we’re the only person or there’s five million and three people, we should think of the teachings as being directed towards us personally, because they are. There’s something for us to practice.

Seeing the teacher and the Buddha as one nature helps us to do that; to really take things seriously and to feel like we have a personal connection there when we’re doing the meditation and also when we’re listening to teachings. Because sometimes it’s always best, especially at the beginning of our practice, to live close to our teacher and to see our teacher regularly. After some time that may not be possible. I mean, I don’t see my teachers very often so this practice of Guru Yoga becomes quite important because then every morning when I’m visualizing the various deities of the Buddha, or whatever, I think here are my teachers appearing in this form and it’s all my teachers. It’s not like it’s one conglomerate personality, so I’m not thinking of their personalities; I’m thinking of their qualities, their wisdom and compassion, and so forth. And they’re all here and I can communicate with them in that way. So that way you don’t feel so separate and far away from your teachers, especially if your teacher has passed away. That physical body’s not there but, that same nature that is the nature of the Buddha is still present, so we still think of our spiritual mentor in that way and we still feel close to them even if they’ve passed away. I find that kind of meditation very helpful because otherwise if I’m far away from my teachers everything’s crazy around me. Then if I think I’m all alone in this boat of samsara, this ocean of samsara, help. Then it’s quite desperate. But if I think okay, close your eyes and visualize the Buddha and Je Rinpoche, and they have the same nature as my teacher. Then you feel like you have some support and understanding and you think of their qualities and a very close feeling comes. So it’s really quite helpful. I strongly recommend doing that.

Also when you have a problem, it can be really helpful because then this comes after you’ve heard a lot of teachings, after a period of years. Then you just close your eyes, visualize the Buddha or whichever deity it is and you think of them as the nature of your teacher and then you kind of voice your problem. And then you’ve heard enough teachings at that time and the answer comes. You just know which of the teachings you’ve heard from your teacher that are applicable to this problem that you have right now. So that’s a very good way to get help when you need it. You’re doing your own internal 911 to the Buddha and then you don’t need to get so frustrated when you’re constantly trying to call your teacher and you can’t get through, or you get their attendant and the attendant doesn’t put you through and things like this. So you have your own direct lines and you don’t have to go through any attendants.

Okay, I got off on a tangent there. Okay, so here you are, visualizing the merit field or the single Buddha or Je Rinpoche with the Buddha at his heart and Vajradhara at his heart.

Fifth Preparatory Practice

Then step five of the preparatory practices is to do the seven-limb prayer. So, what I’m describing actually is, for those of you who have the Pearl of Wisdom, the blue book, these are the prayers that are all listed in there. And I can’t remember, can you remember what page?

Audience: Page 37, the abbreviated…

VTC: The abbreviated recitations, page 37, yes. So this is what it is. You offer the seven-limb prayer. We’ve covered a lot of things, the four preliminaries and we’re doing the six preparatory practices.

Now the four immeasurables and the seven-limb prayer. If you like lists, be a Buddhist. So in the seven-limb prayer, the first one is prostration. This is to generate respect and humility, purify arrogance and create merit. So we either physically bow or we put our hands together like this. And again, we imagine all the sentient beings bowing together with us.

Then the next one is offering. And here we imagine, again, the sky full of beautiful clouds of offering and offer that.

The third of the seven-limb prayer is confession. And here we recall all of our negative actions without trying to justify, or deny, or conceal, or rationalize any of them. We just put them out there with a sense of regret and a determination not to do them again.

The fourth of the seven limbs is to rejoice. So we not only confess but we also rejoice at our own and others’ virtue and merit.

The fifth and sixth ones, sometimes they come in one order, sometimes they come in the other order. Sometimes it’s first requesting your teachers to give teachings and then requesting the Buddhas to remain until samsara ends. Once in a while it’s in the opposite order, and you’re requesting the Buddhas and your teachers to stay until samsara ends and then next request them for teachings. Those are the fifth and sixth.

And the seventh one is dedication. You’re dedicating all the merits for the benefit, the enlightenment, of yourself and others, so you offer the seven-limb prayer. Actually, if you do the King of Prayers, the prayers of the extraordinary aspirations of the Bodhisattva, Samantabhadra, King of Prayers, that’s in the red book page …

Audience: Page 55.

VTC: Page 55? Okay. If you look at the first two pages there is an extended version of the seven-limb prayer. There are several verses of prostration and homage, several verses of offering and then one verse either from confession, rejoicing, requesting them to turn the Dharma wheel, requesting them to remain in samsara and dedication. So that’s the longer version of the seven-limb prayer. Then you offer the mandala. So here, mandala means our universe and everything that’s beautiful in our universe. According to the ancient Indian vision of the universe, it’s flat with a center mountain and four subcontinents—I mean, four continents and eight sub-continents—and then the sun and the moon and all these beautiful things. And so if you do the long mandala it lists out sometimes 25 things and sometimes 37 things, I think. Whether you recite the long mandala or not, you have the idea of all these different objects and you offer that. The idea is to really think of everything beautiful in the universe and instead of thinking, “I want,” which is our usual reaction to anything beautiful, it becomes, “I give, I offer.”

And it’s very nice if you can do the inner mandala offering. I find this one very helpful because here you imagine taking your body and making it into the mandala. Your skin becomes the flat base; the fluids in your body, your blood especially, become the oceans; your torso is Mount Meru; in the center, the four continents are your hands and legs and your two feet; the eight sub- continents are the upper and lower portions of each limb, and then the eyes are the sun and moon and your ears are the parasol and victory banner. Your torso is Mount Meru, so there’s lots of space for a huge stomach in there. Your head is the palace, Indra’s palace, on the top of Mount Meru, and then all of your internal organs are all the beautiful offerings all around. I really like that meditation because I find that it helps me deconstruct my body and practice giving away my body so that I’m not so attached to it. That’s very helpful because attachment to our body makes us so miserable, especially at the time of death. Clinging on to this bag of filth, what’s the sense of that? So it’s much nicer to take it and transform it into this beautiful thing and give it and offer it. So that’s the fifth of the six preparatory practices.

Sixth preparatory practice

And the sixth one is to make requests to the lineage gurus for inspiration by reciting the requesting prayers. He was saying, “complete the six kinds of conduct up to the request that the three great purposes (of self, others and both) shall be fulfilled.” So the request of the three great purposes can be one of the verses that you recite when you’re making requests to the lineage gurus at the time of the sixth preparatory practice. Sometimes in the blue prayer book, that’s when we say, “Precious and …” whenever I recite this.

Audience: This is my root guru?

VTC: “Precious and holy root gurus to the crown of my head.” And then, “the eyes through whom the vast scriptures …,” Do you know that verse? You can recite those as requesting prayers or actually there’s also a whole huge long prayer to the lamrim teachers. You can also do this one, which is found in the Great Treatise on the Stages of the Path by Je Rinpoche, under the section where he’s describing the preparatory sections under the part about requesting to the lineage. So let me read this prayer; it’s quite nice:

Please inspire all my mothers, sentient beings and myself so that we may quickly abandon all flawed states of mind, beginning with not respecting the spiritual mentor and ending with grasping signs of true existence of the two kinds of self. Please inspire us, so that we may easily generate all flawless states of mind, beginning with respecting the spiritual mentor and ending with knowing the reality of selflessness. Please bless us to quell all inner and outer obstacles.

It’s a very nice one. What you’re doing there is requesting that all of our misconceptions about all the lamrim teachings—beginning with meditating on the spiritual mentor and going through the realization of emptiness—that all the obscurations to realizing those be cleared, that all the realizations and knowledge about these come and that all outer and inner obstacles are eliminated. So outer obstacles could be people bugging you and not letting you meditate. Inner obstacles are getting sick or having your mind be in a bad mood.

So those are the six preparatory practices and what we do. Let’s bring it back here to the text. So sweeping the room and setting up the altar, making offerings, sitting in the proper position, taking refuge, breathing meditation, taking refuge and generating your motivation. Then, visualizing the merit field is the fourth one. The fifth one is offering the seven-limb prayer and the mandala offering. The sixth one is making a request to the lineage, including your own spiritual mentor. So that is what is included when we’re talking about the actual session and the preparation part of the actual session. That’s also what he’s talking about in that paragraph there, when he says we should decorate the place, place representations of the three jewels, offer mandala and complete the six kinds of conduct up to the request that the three great purposes shall be fulfilled.

So, we did two paragraphs. We have time for a couple of questions.

Audience: In regard to morning practices, when we’re doing specific deity practices, how do the six preliminaries, as far as some of the sadhanas, have the four immeasurables, the seven-limb prayer and the mandala offering. Some of them don’t. And where is the refuge field in relationship to the deity that you’re visualizing, usually in a sadhana. Do you do all of that before?

VTC: If you’re doing a sadhana practice, you’ll find that most of the sadhanas have this built right in. There’s refuge and bodhicitta, the seven limbs, the mandala offering and there’s some kind of request like the Chenrezig sadhana has it like that: boom, boom, boom, and boom. Vajrasattva doesn’t have it. You have refuge and bodhicitta at the beginning and if you’re doing a deity sadhana you can, when you’re taking refuge, either visualize the Buddha as a central figure, or you can visualize that particular deity as the central figure. Even if the deity practice doesn’t have the seven limbs and you want to add it, there’s no fault. Varasattva’s not going to say, “Hey, what are you doing that for? You shouldn’t be creating all this merit and doing all this purification.”I don’t think Vajrasattva is going to object, so you can add things in if you want to.

Audience: Is there any significance to putting Vajradhara behind the Buddha in that visualization of refuge?

VTC: Sometimes they say that when you do the refuge visualization, that Vajradhara is on the throne that’s behind the Buddha. In that case, that’s where all the tantric lineages would be because Vajradhara is seen as the manifestation that the Buddha appeared in when giving the tantric teachings.

Audience: Would you have had to have had higher class tantra to do that?

VTC: No. You could have, I think, the other classes of tantra as well.

[Dedication ends the teaching.]

More teachings on this topic can be found in the category The Six Preparatory Practices.

Venerable Chodron’s commentary appears in square brackets [ ] within the root text ↩

Original text reads, “… that our lives can end at any time.” ↩

Original text reads, “The actual session is also divided into three—preparation, meditation and behavior.” ↩

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.