Prostrations to the 35 Buddhas

The Bodhisattva’s Confession of Ethical Downfalls

Transcribed and lightly edited teaching given at Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle, Washington, in January 2000.

The Prayer of the Three Heaps

The prayer that follows the Buddhas’ names is called the Prayer of the Three Heaps because it has three parts. The first part is confession, the second is rejoicing, and the third is dedication. It’s also good to memorize this prayer because then you can prostrate while reciting it.

Psychologically, I’ve found it very effective to say all these things that I’ve done wrong while I’m bowing and my nose is on the ground. Somehow, it really hits home that way, whereas when we stop and read the prayer because we haven’t memorized it, the ego isn’t hit quite as hard. So, I would really encourage you to memorize the names and the prayer so that when you do it in a group, you don’t have to stop and read it. Nor do you have to depend on another person or the tape recorder to read it for you. After all, it’s us that acted destructively, not the tape recorder, so we should own up to it by saying it ourselves.

When we do this practice in a group and somebody else is reading, we shouldn’t think that we don’t need to recite the names and the prayer. That’s like thinking the person reading the prayer will purify for us. Or, the tape will purify our negativities for us. But then, does the tape get the good karma? Of course the tape can’t get the good karma because the tape isn’t a sentient being! In the meantime, we miss out on acting constructively if we let the tape say the names and the prayer.

For that reason, the masters recommend that with any of these practices, such as making offerings, bowing, meditating, or reciting, we should do it ourselves. If we do prostrations, we should do it ourselves. If the names of the Buddhas are being said, we should say them ourselves. If we don’t, it’s like someone saying, “Julie, will you eat for me?” and then expecting to be full after she eats. It doesn’t work that way. We have to eat ourselves. It’s the same way with purification. We’ve got to do it ourselves. We can’t hire somebody else to do it for us.

1. Confession

Each of the Buddha’s names starts out with “To the One Thus Gone.” That’s “de zhin sheg pa” in Tibetan or “tathagata” in Sanskrit. “The One Thus Gone” means the one who has crossed over from samsara to enlightenment. It can also mean “The One Gone to Thusness,” “thusness” meaning emptiness. Here we bow to one who has realized emptiness. In the original sutra, the Buddhas’ names didn’t have the preface “The One Thus Gone.” When Lama Tsongkhapa did the practice, he initially had a vision of all the Buddhas but he couldn’t see their faces clearly. As he continued to do the practice, he added “The One Thus Gone” before each Buddha’s name as a way of showing his respect to them, and after that he had a very clear and vivid vision of all 35 Buddhas with their faces. That’s why that phrase is added, though it wasn’t in front of the names initially.

When I was in Tibet in 1987, I was able to visit Okka, the place where Lama Tsongkhapa did his prostrations. Although it was virtually destroyed by the Communist Chinese, you can still see the imprint of his body on the stone where he did prostrations. He did 100,000 prostrations to each of the 35 Buddhas—that’s three and a half million prostrations! It’s high altitude there, with cold weather and only tsampa (ground barley flour) to eat. If Je Rinpoche could do so many prostrations under those conditions, then we can easily do it here with our thick carpeting, a mat under our body, a pad under our knees, and a towel under our head. We can adjust the room temperature to make it warmer or cooler. There is water and even hot chocolate nearby! We can manage it!

This practice of bowing to the 35 Buddhas is from a Mahayana sutra and is also found in the Chinese Buddhist tradition. The Chinese tradition speaks of 88 Buddhas, of which 35 are the ones mentioned here. The prayer of the three heaps is the same too. One time when I was staying at City of 10,000 Buddhas in California, some of the chanting we were doing sounded so familiar. Then I realized that it was this practice. They followed it by reciting The King of Prayers, which is from the Mahayana sutra, the Avatamsaka sutra, which both of our traditions share.

The prayer of the three heaps starts with

All you 35 Buddhas, and all the others.

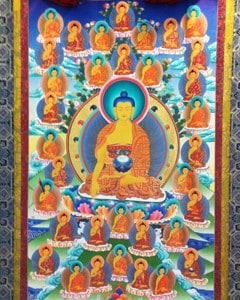

When reciting the prayer, imagine the 35 Buddhas in front of you. Around you imagine all of your previous lives in human form. They are all bowing with you. In addition, remember that you’re surrounded by all sentient beings, who are also bowing to the 35 Buddhas with you.

To make it more elaborate, imagine this whole scene upon every single atom, throughout space. So there are infinite numbers of 35 Buddhas, and our infinite beginningless lives and infinite sentient beings prostrate to the Buddhas. Thinking like this has a powerful effect on the mind. We create much more powerful positive potential and the purification is stronger as well. It really stretches the mind and completely gets us out of our narrow way of thinking and opens us up so we remember all sentient beings.

To all you 35 Buddhas and all the others, those thus gone.

The tathagatas are those who have realized emptiness.

foe destroyers,

or arhats, are those who have destroyed the foe of the afflictions and are liberated from cyclic existence.

fully enlightened ones and transcendent destroyers

are other epithets for the Buddha.

who are existing, sustaining, and living throughout the ten directions of sentient beings’ worlds

“Existing” refers to them having attained the dharmakaya, the mind of the Buddha, and “sustaining” and “living” refers to having attained the rupakaya, the form body of the Buddha. The rupakaya includes the sambhogakaya, the enjoyment body, as well as the nirmanakaya, the emanation body. The ten directions include the four cardinal directions, the four intermediate directions, and up and down. It means everywhere.

all you Buddhas, please give me your attention.

We start out by asking the Buddhas to give us their attention, but what we’re really doing is saying to ourselves, “May I pay attention to you.” The Buddhas are always paying attention to us. We’re just not usually tuned into them. Asking them to pay attention to us is really a psychological tool to remind us to pay attention to them. When we tune into the fact that they’re paying attention to us, that they’re doing their best, day and night, to guide us to enlightenment, that they care about us, then we will automatically pay attention to them.

In this life, and throughout beginningless lives

Think about that for a while. Beginningless lives! That’s a long time.

in all the realms of samsara,

That means that we’ve been born everywhere in cyclic existence, and we’ve done everything in samsara. So there’s never any reason to feel that we’re special or better than anyone because every single action that sentient beings do, we’ve done before in our multiple, beginningless lives. When we seek to purify our negativities, there’s no reason to feel that we’re morally superior to others because we haven’t done all the awful things they have. When we consider infinite beginningless lives, it’s easy to imagine that we have been born in every sort of existence and done every type of action, positive and negative. The only thing we haven’t done in our previous lives is complete the path to liberation or to enlightenment. That means that sometime during our beginningless lifetimes, we’ve all acted like Hitler, Stalin, Mao Tse Tung, and Osama bin Laden. We’ve done everything, so there’s nothing for us to be arrogant about.

Remembering this is helpful because arrogance is a huge obstacle on the path. Thinking that we’re special or better than others creates a big block and impedes our spiritual growth, because if we think we’re already so great, we won’t think to improve ourselves. Then we remain smug and complacent while our precious human life slips by. However, having a spacious mind and being aware of our shortcomings automatically deflates that arrogance. It makes us humble. Then we are receptive to learning. Willing to listen to the advice of the wise, we’ll put it into practice and will reap the benefits.

We’ve been born in the hell realms, as hungry ghosts, and as animals. We have been born as desire realm gods with sense pleasure deluxe. We’ve been born in the realms of the form and formless gods, with great single-pointed concentration. In fact, we’ve been form and formless realm gods, abiding in samadhi for eons, so don’t think you have no ability to concentrate! You’ve been born there with all those abilities before. The point is that we never realized emptiness directly, so when we fell from that state, we kept revolving in samsara.

Now we start confessing, revealing our mistaken actions.

I have created, caused others to create, [negative karmas]

I’ve done it myself. We have asked other people to do negative actions for us; we’ve encouraged their harmful actions. How often do we ask our friends or family to lie on our behalf? How often do we involve others in gossip about people behind their backs or criticizing them? How often have we encouraged others to cheat on this or that? We must reflect on not only the negativities that we have done but those we’ve asked, encouraged, or influenced other people to do.

Sometimes we don’t want to do a certain action because we are concerned that we might get caught, get hurt, or suffer ill effects. So we ask somebody else to do it for us, thinking that then it’ll be their problem to deal with. But, karmically, that doesn’t work. If we ask somebody else to commit a negative action, we get the same karma as if we did it ourselves because the motivation came from us. So here, we’re confessing all the negative influence we’ve had on others.

Sometimes the people we have a harmful influence on are the people we love the most. The people we’re closest to are the people that get involved in our gossip and divisive speech, in our schemes and shady business deals. They’re the ones that we ask to steal for us, to lie and cover up for us when we’ve done something wrong. It’s the people we love that we incite to speak harshly in order to stick up for us when we’re in a quarrel. It’s the people we love that we provoke to anger and harsh words by our obnoxious actions.

We need to think about this seriously. From a karmic viewpoint, are we helping or harming our dear ones? If we care about them and think about their future lives and enlightenment, would we still act towards them the way we do?

I have created, caused others to create, and rejoiced at the creation of negative karmas

Not only have we done or asked other people to do destructive actions, but when we’ve seen other people do them, we’ve said, “Great!” “The US forces bombed Baghdad? Fantastic!” “They killed some suicide bombers? Super!” “My colleague lied to the boss and we all got more time off? Wonderful!” “This murderer was just sentenced to death. Great!” It’s very easy for us to think like that, isn’t it?

In other cases, we rejoice at others’ misfortune. “They caught that dishonest person and threw him in the can. I’m glad. I hope he gets beaten up in prison.” “The reputation of a person I’m competing with just got trashed. Hooray!” “This politician whom I don’t like is getting indicted? Finally!”

It’s extremely easy to rejoice at harmful actions others do or rejoice at others’ misfortune. Especially when we watch movies or the news or when we read the newspaper, if a part of our mind thinks, “Oh, good,” about the effect of another’s harmful action, we create negative karma. So we have to be very careful and watch our mind when we’re in contact with the media because it’s easy to be judgmental and rejoice in others’ negative karmas, especially if we get some worldly benefit from it. Here, we confess all of this.

Next, some of the heavy negative karmas we’ve created are delineated. These include misusing offerings to holy objects. For example, we take things offered on an altar for our own personal use. It just happens to be lunchtime and we’re hungry and there is food on the altar so we’ll eat it. A friend stops over unexpectedly and we don’t have any cookies or fruit, so we take some from our altar to give him. Or if we go to a holy place and take things on that altar because we want a souvenir. People do this, let me tell you. When I first heard teachings on this, I wondered, “Who in the world would do these things?” Well, since then, I’ve seen and heard of people doing these actions. People go to Bodh Gaya and want a souvenir from the altar in the main shrine to put on their altar. They take it without asking anyone. It happens.

This also includes the case of someone giving us something to offer to the Three Jewels and we don’t offer it. For example, somebody gives us some money to offer at the temple at Bodh Gaya, and we spend it on ourselves. Or someone gives us a gift to give to her teacher, and we forget. Later when we remember, we think, “It was so long ago. I’ll just keep it for myself.” Or, someone gives us some cookies to offer to the sangha at a monastery, and we get hungry, eat them, and think that we’ll buy some other ones. No! When somebody has given something specific to offer, we have to offer exactly that thing and not think that we’ll use this one and replace it with something else. Once something has been mentally offered, it belongs to the Three Jewels; it doesn’t belong to us. All these actions and others are included in misusing offerings to holy objects.

Misusing offerings to the Sangha is misusing things that have been offered to the Sangha as a community or to arya Sangha as individuals. If we’re managing the Sangha’s money or an individual Sangha member’s money and misuse it, the karma is very heavy.Borrowing the possessions of a sangha community and not returning them, taking their things without asking permission, misusing Sangha property are included in misusing offerings to the Sangha.

Stealing the possessions of the Sangha of the 10 directions. The Sangha of the 10 directions refers to the entire Sangha community. The negativity created with the Sangha community is much heavier than other negativities because the object is a community. For example, if someone takes something from a monastery without asking, they have stolen from however many people there are in the community. If he wants to go to the Sangha and confess, he has to confess in front of the entire community. However, it’s not always the case that the same people who were in the community when he stole are still there when he returns the item and confesses. That makes it difficult to purify the transgression.

We have to be very careful around the Sangha community and its property. Those who are monastics can’t offer things belonging to the Sangha community to their relatives. They can’t give away the Sangha’s property without checking either with the manager of the community or with each member. Monastics can’t take Sangha property for themselves, especially money offered to the Sangha community. We have to be extremely careful with that.

It specifically mentions the Sangha here instead of just sentient beings of the 10 directions because the negative karma is especially heavy stealing from those who have dedicated their lives to attaining liberation or enlightenment. The power of the object is greater. Sangha are people who have dedicated their lives to practicing the path. Having taken precepts, they are fully intent on gaining liberation and enlightenment. Therefore, depriving them of the means of their livelihood is much more serious than stealing from someone who is not intent on liberation, or someone who works for a living or has an income.

Actions, either positive or negative, done in relation to our spiritual mentors, the Buddha, Dharma or Sangha become very powerful. Why? As the object in relation to whom we act, they are very virtuous. Our mind has become very cloudy if we think virtuous beings are just like everyone else and treat them inappropriately. That doesn’t mean we idolize them. Rather, we respect their virtue because we want to be like them.

We create a lot of good karma or a lot of negative karma in relation to virtuous objects. One of the reasons why it’s possible in tantra to attain enlightenment in one lifetime is because when we see our guru as an emanation of the Buddha and make offerings, we create incredible amounts of good karma. It’s very, very powerful good karma. On the other hand, if we get angry, we create very, very negative karma because it’s like getting angry with all the Buddhas. So we have to be very careful around the beings who are virtuous objects.

The prayer speaks about misusing offerings to the Sangha community. To broaden that a little, we have to be careful about the actions we do in relationship to a Dharma center. Although it is not as strong an object for the creation of karma, it is stronger than many other things in our life. For example, we may borrow books or tapes from the center’s library and not return them. This is stealing from the Dharma center. Someone managing the center’s finances may be careless, or worse yet, deliberately take money from the center. The person in charge of doing a certain job may keep extra supplies for themselves. We must be attentive and conscientious here. Conversely, offering service to a Dharma center or monastery, making offerings to them, as our monthly supporters do, assisting in organizing activities are actions that create a lot of positive potential. Why? Because the object is virtuous and because we’re helping sentient beings to meet the Dharma, which is the true source of benefit and aid that will cure their suffering.

“I have caused others to create these negative actions and rejoiced in their creation.” We admit that we have engaged in, encouraged others to do, or rejoiced in many negative actions, specifically those in relation to holy objects. Instead of pretending we haven’t done these in this or previous lives, we release the immense energy involved in denial and acknowledge our mistaken deeds. Honesty brings a tremendous sense of relief.

I’ve created the five heinous actions, caused others to create them and rejoiced at their creation.

These five are killing our father, killing our mother, killing an arhat, causing a schism in the Sangha community, and causing blood to flow from the body of a Buddha. Actually, some of these can only be done at the time of the nirmanakaya Buddha, but still we can do things that resemble such actions. We have to be especially mindful of not causing schism and disharmony in the Sangha community. This refers to dividing people into different groups through political means, gossip, or any other way. Why is this harmful? Because the Sangha members don’t function harmoniously together as ones intent on virtue but instead quarrel with each other, fighting over this and that. They waste their time, and people in society then lose faith in the Sangha. So, it’s extremely important not to cause schisms in the Sangha. We can extrapolate that to people in a Dharma center; we should not provoke them to engage in gossip, rivalry, or politics. Who can practice Dharma in a center where everyone is busy creating negative karma in a big power struggle?

There are various controversies in the Tibetan community nowadays. I recommend that we don’t get involved in any of them. Just be aware controversies exist and keep a distance. We come to the Dharma center for the Dharma, not for politics, and so we listen to the Dharma and practice it. If other people want to get involved in controversies, so be it, but we stay away and avoid creating a lot of negative karma.

We might think, “I would never do any of the five heinous actions.” Well, check up. What if one of our parents says, “I don’t want to live any longer. Please help me kill myself. I’m in too much pain.” Of course, that’s not the same as killing a parent out of anger, but still if we assist them it’s contributing to our parent’s death. In our monastic vows, even encouraging death is a root downfall. We have to think carefully about that. We may think, “Who in the world would kill their mother?” I went to high school with a guy who went home one day and shot his mother and himself. I grew up in a “nice middle-class community,” where things like that aren’t supposed to happen. In addition, since we’ve been under the influence of ignorance, anger, and attachment since beginningless time, there’s the possibility that in a previous life we did these five heinous actions.

I have committed the ten non-virtuous actions, involved others in them, and rejoiced in their involvement.

We might think that we don’t do the ten destructive actions very much. But we have to check up! Really check up, and check up closely. Are we really free from killing even little tiny beings like mosquitoes? We might think, “Oh, I didn’t actually see it!” when actually, we did. We need to see the ways we justify or rationalize our harmful actions.

We may think, “I don’t steal.” Check up to see if we repay and return exactly what we borrowed. Do you pay all your taxes and fees that you’re required to pay? Do you use office supplies for your own personal use? Do you make personal long distance calls that are charged to your workplace? All those things fall under stealing.

What about unwise sexual behavior? Look to see if you use your sexuality wisely and kindly, or if you’ve used it to manipulate others. Has anyone been hurt physically or emotionally because of the way you’ve used your sexuality? Many people nowadays easily get involved in unwise sexual behavior but don’t realize it until afterwards. This is something to be attentive about so that we don’t create problems for ourselves or suffering for others.

Check up to see if you lie. It’s incredible. We might think that our speech is exact, but when we look closely, we find that we exaggerate. We emphasize one part of our story and not the other part so that the listener gets a skewed view. That’s deception, isn’t it?

How about divisive speech? We’re upset with somebody and talk with our friend about it. And of course, my friend sides with me and gets mad at that same person.

It’s easy to talk behind someone’s back, use harsh words, or say very rude and insulting things to other people. We do it often. Sometimes we accuse others of doing, saying, or thinking things that they haven’t. We don’t bother to check with them what their actual intention was, but instead jump to conclusions and accuse them of doing this, that and the other thing. Or, we tease them or make fun of them, especially little children, in a way that hurts their feelings. Or sometimes we’re rude, judgmental, and unappreciative of other people. How much are we aware of what we do, say, and think? How honest are we with ourselves? We should avoid being smug, thinking, “Oh, ten negative actions. No problem,” or “These are small things. They’re not so bad.” These ten cover all aspects of our life. If we truly want to attain enlightenment, we must begin by abandoning gross harmful actions. We can’t do high practices when our daily life behavior is a mess!

Let’s examine if we engage in idle talk. How much time do we spend over things that aren’t really important? Do we waste a lot of time hanging out, talking about frivolous things just to be amused or to pass time?

Then there’s coveting. How much time do we spend planning how to get the things we want? “Oh, this is on sale. I really want to get it. This sweater is so nice. This sports equipment is such a bargain.” Meanwhile our closets are stuffed with things we seldom use.

There’s malicious thought. How much time do we spend writing nasty emails or nasty letters in our minds to other people. Do we frequently think about how to hurt somebody by telling them about their faults or rubbing in their mistakes? We spend a lot of time thinking about how to get our revenge for a hurt someone has done to us.

Wrong views are negating something that exists such as karma and its effects, the Three Jewels, past and future lives. Wrong views can also involve asserting something that doesn’t exist, such as a creator god. Many times we aren’t even aware of our own wrong views—this is a dangerous situation, for not only do those views cause us to do other unethical actions, but also we may teach them to others. Some people think they teach the Buddhadharma, but in fact, they teach their own opinions.

We’ve involved others in these 10 negative actions. How? We gossip with our friends and talk behind other peoples’ back with our friends. We spend hours coveting things with our friends, and rejoiced in their involvement. We also rejoice when others do the 10 destructive actions. These 10 are not at all difficult to do!

Being obscured by all this karma, I have created the cause for myself and other sentient beings to be reborn in the hells, as animals, as hungry ghosts, in irreligious places, amongst barbarians, as long-lived gods, with imperfect senses, holding wrong views, and being displeased with the presence of a Buddha.

These nine correspond to the eight unfree states in samsara. To have a precious human life with full opportunity to learn, practice, and realize the Dharma, we must be free from these states. Our negative actions cause us to take birth in these states. This is one of their disadvantages.

All this karma obscures our mind so that we can’t gain the realizations of the path. It obscures our mind so that we continue acting in foolish ways, harming ourselves and others. This karma obscures our mind to the point that we don’t even realize our mind is obscured.

We can’t go back in time and undo the past. We harmed others, but we’ve harmed ourselves just as much or even more because we’ve obscured our own mind with these negative karmic imprints. That’s why we have so many obstacles and difficulties in our own Dharma practice. That’s why we can’t meet qualified Dharma teachers, why we can’t receive the teachings we want, why we can’t stay awake during teachings, why we don’t understand the Dharma, why we don’t have the conditions to do long retreat. All of these happen because our mind is full of obscurations.

All the unpleasant things we experience in our life and all the obstacles in our Dharma practice come because we’ve created negative karma to experience them. Not only are we obscured by all this karma, which causes us not to be able to think or see things clearly, but also we’ve dragged other sentient beings into our harmful activities so that their minds are obscured by their negative karma.

If we’ve created any of the ten non-virtues with all three parts—preparation, action, and completion—we have a 100% perfect negative karma ready to send us to a lower rebirth. We’ve created negative karma to be reborn as animals. Imagine what it would be like to be reborn as an animal, or as a hell being, or as a hungry ghost. We’ve created the cause to be reborn in all these places, and then once we’re born there, what will we do?

Spend some time thinking about what that would be like, how you would feel living like that. Imagine being born in an irreligious place, a place where it’s very difficult to meet Dharma teachers or hear teachings. If we live amongst barbarians, we live in a place where Dharma isn’t available. Fifty years ago the USA was a barbaric country. What would we do if we were born somewhere with no access to the Dharma? Imagine having intense spiritual yearning and aspiration, but there was no one to teach you, no books to read, no access to the Dharma. Then what would you do? Then you’d really be stuck. There would be little happiness in that life and because of not meeting the Dharma, it would be difficult to learn about karma and thus difficult to create the cause for happiness in future lives or for liberation.

Think of people living in Communist countries or places where there is no respect for religion at all, where it’s very difficult for the people to meet the Dharma or have any kind of spiritual instruction that would uplift their minds. Think of the Buddha’s teachings on emptiness and how precious they are. What would you do if you were born in a country where there was a religion that taught ethical discipline and kindness, but nothing about emptiness? Not hearing teachings on the nature of reality, you wouldn’t know how to meditate on it, so you had no chance at all of realizing it directly. Thus liberation was out of the question. Your whole life would be spent doing this and that, going here and there, but it would be totally meaningless because there was no possibility of liberation or even working towards liberation.

Think of people born in a central land where the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha exist but their minds have no interest in the Dharma. In Bodh Gaya, India, there are many street vendors trying to sell religious objects, but they don’t have faith in them as religious objects. They sell them to make money, but actually making one’s livelihood selling religious objects with the same attitude you’d have selling used cars—to make as much money as possible—creates a lot of negative karma.

We’ve created the cause to be born as long-lived gods. Some gods have super-duper deluxe sense pleasure. Others are spaced out in perceptionless samadhi. But no matter how much pleasure we have in samsara, it ends. Even if we have three eons of pleasure, it’s going to end, and what do we do when it ends? This situation is not satisfactory. As they say, samsara sucks.

We’ve created karma to be reborn with imperfect senses, to be reborn with sensory impairments. People with sense defects are not inferior, but they face greater obstacles to learning the Dharma. People with sight impairments can listen to teachings but their selection of Dharma books in Braille is limited. People with hearing impairments can read a lot of Dharma books, but it’s hard to receive teachings. As an aside, I must say it always makes me happy when someone is signing at a talk I give.

Many years ago I was invited to teach in Denmark. The woman who arranged the teaching worked in a hospital for handicapped children, and I asked her if I could visit them. The Danes have really nice social institutions. I went into a beautiful room with so many brightly colored toys and pictures. It was an extravagant children’s place, but I didn’t see any children because I was distracted by all the colors and stuff. Then, I became aware of groans and moans and really strange sounds. I looked around and amidst these gorgeous toys were severely disabled kids. Some were lying in cribs while others were draped over things like skateboards that they paddled around on. That’s the only way they could move. They were so severely disabled that they were just lying around, unable to move. Here they had this beautiful place to live in and so much wealth. They had the best that money could buy, but they were so limited mentally and physically. It was very sad.

Very easily, we could be reborn like that. Think about the karma we’ve created! How many times have we said, “What are you, stupid or something?” That creates the karma to be born stupid. Or we say to people, “Are you blind?” when they can’t find something. Or “Are you deaf?” when they don’t hear what we said. Calling people names creates the karma to have those disabilities ourselves. We have to be very careful about what we say!

We have also created the causes to be reborn as someone who holds wrong views. If we look at the wrong views we’ve held this life, we see we may have created the cause to be born in the future as someone who believes in a permanent soul or an inherently existent creator, or somebody who has wrong ethical standards and thinks killing is good. Would we like to be born as someone who is attracted to strange religious cults or to illogical views?

Regarding being displeased with the presence of a Buddha, we could be reborn as someone who has the opportunity to practice and study the Dharma but is extremely critical of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, someone who is hostile to Buddhadharma or to the Buddha himself. What would happen to us then? Being born in any of the above situations would make learning and practicing the Dharma very difficult.

We have to think about this in depth. “I have all these karmic imprints on my mind. What happens if I die soon and these imprints ripen? How will that impact me?” Thinking about this, we may find that we’re concerned and worried. We want to purify these karmic imprints, but don’t know how long we have left to live. We have no idea when we’ll die.

We may think, “That’s okay, when I die, I’ll meditate and will therefore have a good rebirth. “Think about it: Can we control our mind well enough so that when we die we will surely take refuge, generate bodhicitta, and meditate on emptiness? Let alone be able control our mind when we’re dying, do we even remember to offer our food before we eat each day? If we can’t remember to offer all our food when we’re healthy and calm, how are we going to remember to take refuge when we’re dying and our whole world is discombobulated? So, we shouldn’t be smug or arrogant and think that we’ll be able to do taking and giving (tonglen) when we die and be born in a pure land, no problem. Just look at how we respond when someone says something we don’t like. Do we respond with kindness and bodhicitta or do we respond with anger? It’s very clear, isn’t it?

The point is that if we die and these negative karmas are still on our mind, there’s a very good chance that some of them will ripen. That creates this sense of urgency, doesn’t it? It may generate some fear. There are two kinds of fear: one is useful and one is useless. If there’s an actual danger, being afraid of the danger is useful, isn’t it? If there’s danger of the ozone layer being completely depleted and life degenerating on this planet, it’s good to be concerned about that happening because then we’ll do something to prevent it. If there’s a chance of an accident when we’re merging on the freeway, we’ll look where we’re going to avoid an accident. That kind of fear, that awareness of danger, is very positive. It is not neurotic fear. The word fear doesn’t have to mean being in a panic, neurotic, uptight, trembling, and having a completely frazzled mind. Fear can just mean an awareness of danger, and that kind of fear is useful because then we’ll work to prevent the danger. For example, if the flu is going around and we don’t want to get it, we take extra care, don’t we? We drink orange juice and take vitamins. An awareness of danger can be a positive thing.

The kind of fear that is useless is the panicked, emotional fear that makes it impossible for us to act because we’re totally immobilized. If we’re so afraid of getting sick that we stay in a stuffy house all day, we defeat ourselves. Similarly, the kind of fear or concern stimulated by thinking about the karmic consequences of our actions shouldn’t be the panicked, neurotic kind of fear. If it is, then we have to realize that we’re not thinking correctly, that we’re not getting the point that the Buddha intended when he told us about the eight unfree states. The Buddha intended for us to be aware of the danger of our unskillful actions so that we can prevent them; his goal wasn’t for us to become frazzled and immobilized.

Sometimes hearing unpleasant things is useful because it activates us. If we know that there are certain medical problems in our family and a tendency for us to get a certain disease, we take special care in those areas, don’t we? It’s the same idea here. We need to take special care of our actions and by doing so, we prevent unwanted consequences.

Audience: Can’t we become overly pious, trying to be good Buddhist boys and girls, acting as if there were some guy with a clipboard somewhere writing it all down? But, that’s not how it works. Through our thinking and our acting, we sow seeds, and the seeds that we plant grow.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): This is a good point. I’ve noticed that those of us who grew up in Judeo/Christian cultures often have a childish mentality about causality and karma which we learned in Sunday school when we were young children and still believe at some level. It’s especially important for us to be aware of the attitudes we grew up with that we unconsciously internalized. We probably aren’t even aware of some of these attitudes until we find ourselves thinking like you mentioned, and drawing the conclusion that Buddhism feels too confining, just like some of the beliefs we grew up with and later rejected. We might think that our attitudes are consistent with the Dharma. This is a stage that many of us go through, and if it isn’t this, another aspect of the Dharma will remind us of the children’s Sunday school version of religion that we learned and rejected. It’s important to be aware of this and to notice what we’re thinking and when we’re projecting the attitudes that we grew up with onto the Dharma.

As you said, the point of talking about actions and their effects is not to make us into nice, pious, super sweet little Buddhist boys and girls. Instead we’re trying to become normal, healthy human beings who see things realistically. But we have preconceptions that we’re not always aware that we have. We don’t realize we have this kind of conditioning until we find ourselves fighting with some aspect of the Dharma. Be aware of this and keep an eye out for it.

Audience: Perhaps part of our difficulty is that we want a very simple explanation of what karma is, and we don’t appreciate its complexity.

VTC: Yes, that’s a good point. We want a simple explanation of karma and we don’t appreciate its complexity, but when we get the simple version of karma, we say that it sounds too much like kindergarten Sunday school. Some Dharma texts on karma say that one will be reborn in a hell realm for any misdeed done physically and will be reborn as a hungry ghost for any misdeed done verbally. This is very simplistic. Some people think, “I killed a gopher and now I will be reborn a gopher.” We can have a simplistic outlook that overlooks the fact that one action can bring many results and that other times many actions must be created to bring one result. We aren’t aware of the complexity and subtlety in terms of the motivation of our action, the object we do the action with, the frequency we do the action, the regret or lack thereof after we did the action, and so on. Many factors condition the heaviness of a karmic action, and many other factors condition when, where, and how it ripens. Sometimes we want simple teachings about karma, and then have a very rudimentary understanding about it. But then, that simplistic understanding makes us angry because it sounds too black and white, or kindergarten-ish, or too much like being in prison. In that case, rather than blame the Buddha or the Dharma, let’s learn and reflect more to deepen our understanding and make it more sophisticated.

Meditating on karma, especially the various factors that make a karma heavy, is effective. It gives us an inkling of the complexity of conditions affecting an event. Then think about your own life and how you make your positive or negative action heavy. Let’s contemplate how to strengthen our positive actions and how to diminish the strength of negative ones?

Let’s contemplate the various results brought about by an action done with all the branches complete. When we meditate on the results of karma, we realize there’s a lot of flexibility in terms of the specific ways a karmic action ripens. Although a negative karma will always ripen as unhappiness and a positive one as happiness, exactly how it ripens, for how long, to what extent, and so on are not written in stone. These are flexible because they are conditioned by many factors. So don’t mistake karma with predetermination or fate. It’s not.

Now before these Buddhas, transcendent destroyers who have become transcendental wisdom, who have become the compassionate eye, who have become witnesses, who have become valid and see with their omniscient minds, I am confessing and accepting all these actions as negative. I will not conceal or hide them, and from now on I will refrain from committing these negative actions.

This is the last paragraph of the confession part of the prayer. Here we sincerely call out to the Buddhas to witness our confession. We earnestly reveal to them, without neurotic shame or self-hatred.

“Transcendent destroyers” is the translation for “bhagavan” in Sanskrit or “chom den de” in Tibetan. “Chom” means to destroy the defilements, “den” means to be endowed with or to possess all good qualities and “de” means to go beyond or transcend cyclic existence. These transcendent destroyers have become transcendental wisdom; that is, they directly know all phenomena in general, and in particular see all our constructive and destructive actions, their causes, and their results. They’ve “become the compassionate eye” because they view our actions with compassion, not with judgment. This certainly is different than us, isn’t it? We aren’t able to see the causes and effects of actions, yet we judge them and the people who do them. Wouldn’t it be nice to be a Buddha and be free from our judgmental, critical mind?

Think deeply about the Buddhas’ compassion when making confession. Don’t feel like a guilty little kid who got caught doing something wrong or who broke somebody else’s rules. Let go of the fear that somebody will judge us. Don’t get into that habitual frame of mind, but remember that the Buddhas see us and our actions without any judgment, just with compassion. That example gives us a model of how we can look at other people—having compassion for others who make mistakes, not judging them. It also gives us a model of how to look at our own mistakes—to have some compassion for ourselves and not get down on ourselves. This point is very important!

They “have become witnesses.” Buddhas are able to witness our excellent as well as our faulty actions. They also witness our confession. We’re not revealing our faults in thin air, but in front of the Buddhas who witness it with compassion. They “have become valid” in that they correctly and infallibly understand karma and its results. They are also valid in their perception of emptiness, recognizing that all of our karma is empty of inherent existence.

They “see with their omniscient minds.” They know all objects clearly and directly. They say a Buddha can see everything, including the link between specific actions and their particular results, as clearly as we see the palm of our hand.

“I am confessing and accepting all these actions as negative.” When we say, “I confess them,” it means that I regret them. Of the four opponent powers, this is the power of regret.

“Accepting all these actions as negative” means we admit that we did them. We’re being honest with ourselves and with the Buddhas. Psychologically, this is quite healthy. We’re not saying, “Well, I did it but it was actually somebody else’s fault,” or “I didn’t really do it,” or “I didn’t mean that,” or any of the other rationalizations that we usually use.

In my correspondence with prisoners, I find very touching the degree to which they can accept and regret what they’ve done, at least. This isn’t saying all inmates are like this, but the ones who write to people like Venerable Robina and me are; they are reaching out for help and are so grateful for anything we do. They’re using their time in prison to take a good look at themselves. I suspect other inmates are angry and still blame others, but these particular men who are doing spiritual work while in prison have a level of honesty about their actions that is really admirable. It’s the same type of honesty that we want to develop here when we’re saying this prayer. We just say, “I accept it. I did it,” without being ashamed or defensive. We just regret what we’ve done. Implied in that is a wish not to do it again.

“I will not conceal or hide them.” Not concealing it means that from the moment they have been committed, we have tried to keep them secret. In the Pratimoksha vows, if monastics conceal something when they commit a transgression, it becomes a heavier breach than if done without any thought to conceal it. It would help us a lot to look at our habit of concealing our negative actions. When we make a mistake, how often is our knee-jerk reaction to conceal it? “Nobody else knows. I’m not going to tell anybody. I’m not going to admit I did it. I can make up some excuses.” Here, we’re saying that we’re not going to do that.

Not hiding it means that we’re not going to say we didn’t act destructively when we did. We’re not going to lie about it. Concealing is not telling anyone, and hiding it is adding some dishonesty by pretending the exact opposite. We’re not going to do either of these.

“And from now on, I will refrain from committing these negative actions.” This is the power of determining not to do those harmful actions again. This determination keeps the karma from increasing. One of the four general qualities of karma is that it expands. In other words, a small action can gestate in our mind and produce a big result. If we don’t purify the karmic imprints of destructive actions, they can increase in potentiality and bring big results. Confessing prevents that. Positive imprints also expand to bring big results unless we generate anger or wrong views which destroy them.

We will be able to say very clearly that we won’t do some actions again. With other actions, we may need to be more realistic and set a specific time, making our pledge not to do it again for however long we think we can avoid repeating the action.

Four doors through which downfalls occur

In addition to determining not to do those negative actions again, we should do our best to close the four doors that lead us to break precepts. These can apply to other harmful actions, too, not just those directly specified in precepts.

Ignorance

The first door through which we create negativities or break precepts is ignorance. We don’t know that an action is negative. Or, we may have a precept but don’t know what it means. If we don’t study our precepts, learn about karma, or remember what we’ve learned, it becomes very easy to create a lot of negativities.

The antidote to this is to learn about our precepts and about karma. We should request our spiritual mentor or preceptor for these teachings and study this material in reliable books.

Lack of respect

The second one is lack of respect. We may lack respect for our precepts or for ethical behavior in general. We might not be ignorant of what constitutes constructive and destructive actions and we may know we’re doing something negative but we don’t care. We might think, “All this talk about karma doesn’t really matter. They say this action is destructive, but I really don’t care.” Or, “I’m going to do what I like. As long as I don’t get caught, it’s okay.” We can easily break our precepts or commit negativities that way.

The antidote to that is to cultivate faith and deep conviction in the workings of karma. In addition, we should think of the value of ethical discipline and of holding precepts.

Lack of conscientiousness

Then the third door is lack of conscientiousness. Here we are reckless and don’t care what we do. “I feel like doing this so I’m going to do it.” We are rather flippant about the whole thing, and just following whatever impulse comes into our mind.

To counteract this, we cultivate mindfulness, introspective alertness, and conscientiousness. Conscientiousness is a mental factor that has respect and regard for what is wholesome. Mindfulness is a mental factor that focuses on a constructive object in such a way that we don’t get distracted by other things. In the case of ethical discipline, it’s awareness of our precepts and of positive actions. During our daily life we remember what we aspire to practice and what we aspire to abandon. We don’t get distracted by appealing objects or activities that would take us away from what we value. Introspective alertness is a mental factor that checks up and sees what’s going on in our mind. It is aware of what we are doing, saying, thinking, and feeling. It checks up if we’re doing what we set out to do.

Some Buddhists often say, “Be mindful.” This actually refers more to introspective alertness. The various Buddhist schools might have slightly different definitions for these mental factors. In the Tibetan traditions, introspective alertness is the one that’s aware of what we’re doing and what we’re thinking about. If it notices that we’ve forgotten the thing we wanted to keep in mind and we’re getting distracted from it, then it invokes other mental factors which are antidotes to distraction or dullness and they bring us back to being mindful of whatever we wanted to focus on.

Having disturbing attitudes and negative emotions in abundance

The fourth door through which we create negative actions is having disturbing attitudes and negative emotions in abundance. Our cup runneth over with garbage mind. Sometimes we’re not ignorant of the precepts or what’s positive and negative. We know. And, we are conscientious. We recognize what we’re doing, we know its disadvantages, but we go ahead and do it anyway. That happens when our afflictions are very strong. For example, have you ever been in the middle of saying something and thought, “Why don’t I just be quiet? Saying this isn’t going to go anywhere good,” but we keep on saying it anyway? This happens because at that moment one or another disturbing emotion has manifested strongly in our mind.

The way to counteract this is to apply the antidotes to the afflictions. We become more familiar with the meditations on patience to quell anger, on impermanence to counteract attachment, on rejoicing to counter jealousy, and so on.

By being aware of these four doors and closing them, we will be able to abide by our determination not to do harmful actions again. So it’s good to remember these four and to try to practice them.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.