Being a Dharma community

I was the resident teacher at Dharma Friendship Foundation (DFF) in Seattle for 10 years. One of my aims, in addition to giving people a good general understanding of the path to enlightenment and getting them going in meditation practice, was to create a sense of community. Most people in the West long for community, but aren’t sure how to create it. They also have very full lives. Furthermore, some people have a certain hesitancy about being part of a community.

One day a DFFer commented me, “When I know that you’re not going to be in class on Monday night, I don’t want to drive all the way to the center to meditate. Especially after a long day at work, I figure I can just do the practice at home.”

I asked her, “Do you meditate at home then?”

She looked a little abashed and mumbled, “Not always. Sometimes I get distracted by something else, or I tell myself I’ll rest a while and then meditate, but I usually don’t get around to it.”

“When you do meditate at home then, are you as concentrated?”

Again the response was an embarrassed, “No.”

Our Dharma friends—the people who attend the same meditation group or Dharma center that we do—are precious. They know and respect something about us—our spiritual longings and aspirations—that not everyone else in our lives do. When we are with them, our practice becomes firmer. They encourage us and give us the support we need to continue on the path.

Similarly, we reinforce and rejoice at that special and precious part of them. The ripple effects from this spread beyond the people who are there, for each of us takes what we receive from the Dharma community with us to everyone else we encounter.

Don’t think that you go to a center or a group just for what you can get out of it. Dharma is about giving. The path to enlightenment is about caring about others. Thus, we share our energy with others when we join the group for practice or discussion. We have something to contribute to others. This needs not be great insights, but simply our presence, our efforts to develop a kind heart and to work with our mind. Don’t underestimate what you have to offer.

One of my teachers said, “You learn 25 percent from teachings and 75 percent from discussing and practicing together with your Dharma friends.” In Tibetan monasteries, the education program is set up to maximize the benefit of sharing the Dharma with fellow practitioners. Students have classes with their teachers for an hour a day and spend several hours after that that discussing and debating the teachings together. This is in addition to their group prayer and meditation sessions. Throughout the centuries, there has been an emphasis on practicing and sharing the Dharma together as a group.

An analogy may be helpful. If we sweep the floor with one strand of grass, it takes a long time. If we sweep it with a broom, it is cleaned quickly. When a group comes together for a virtuous purpose, each individual rejoices and shares in the good karma created by his friends. This becomes a powerful way to create a lot of positive potential in our lives.

Reflect on all the groups you have belonged to or participated in during your life. Attending a football game creates collective energy or karma with the others there. So does being in the army, taking classes at a school, joining family activities, working in an office or factory. How many of these groups have developing a kind heart as their raison d’etre? What emotions and attitudes arise in you when you participate in these groups? Looking at it this way, we see the specialness of those who come together to learn and practice the Dharma. These people, like us, want to purify their minds, develop their qualities, and contribute to the wellbeing of the world. Being with them is an honor and a blessing.

When we practice together with others we give and receive energy to practice and this makes it easier to concentrate. A friend and I began a Dharma Youth Group at DFF for teenagers. We meditated together twice during the two-hour meeting, and they loved it!! (Have you ever seen a teenager blissed out after visualizing the Buddha? The teens told us that it was easier for them to meditate together as a group than alone at home because they gave each other energy, discipline, and confidence.

When I visited a Dharma center in Mexico, two women told me that they met together three or four times a week to practice. Sometimes one or the other of them would be busy or tired, but she would thought, “My friend is counting on me to practice with her, so I’ll go for her benefit.” After they practiced, they always felt glad that they had come together, even if it sometimes required some effort just to get there to do it. By having an attitude that wanted to help each other, both received benefit.

Two friends in Portland for years have meditated together by telephone two or three times a week. They make scheduled appointments. One calls the other; they greet each other and check in and then set their motivation. Having done that, they set the phone down so no one else can call during that time. A bell rings at the end of the allotted time, they pick up the phone and dedicate the positive potential together. Whenever I see them, they express their appreciation and gratitude for their Dharma companion. In addition, the progress each of them has made in his or her practice is evident.

Discussing the Dharma together clarifies our understanding. Sometimes we think we comprehend a particular concept in the Dharma, but when someone asks us a question, we realize that our understanding isn’t that clear. This is valuable, for we learn where to strengthen our practice.

On the other hand, sometimes we think we don’t understand a practice very well, but when we discuss it with others we surprise ourselves and are able to share our experience and understanding clearly. Other times we learn that our Dharma friends have similar doubts or difficulties and that we’re not the only one. When we have a problem in our practice and don’t discuss it, our mind often spins in circles and we get more confused. Then we think, “I’m more confused than others. There’s no way for me to progress,” and lose the self-confidence necessary for a successful practice. Simply sharing our difficulties out loud with Dharma friends often relieves tension inside us. Our friends listen nonjudgmentally, for they too face the same challenges. Then we discuss and share possible solutions together and all of us leave with renewed enthusiasm.

The great majority of Dharma centers in the West do not have resident teachers. People practicing together on a regular basis and the visits of guest teachers sustain them. I have been a guest teacher in many centers in the West and find a great difference teaching in those places where a group meets consistently versus places where people only come together for visits from guest teachers. The people in groups that practice care deeply about the Dharma. I know that they will put into practice some of what they learn when I’m there. There is a definite community feeling, and as a teacher, I know my meager effort to help won’t disappear into empty space after I leave. Because people practice together in the interim, I and other teachers make it a point to visit these groups each year.

Receiving teachings is a result of our actions. When a group practices together, their collective energy and karma have the power to bring teachers there. A teacher is willing to travel all the way across the country to teach in a Dharma center. If that center didn’t exist or if there weren’t a group practicing together, no one would have made the invitation. Even if someone had, it’s unlikely that one individual has enough positive karma to invoke Dharma teachers to that place. Teachers are more likely to undergo the difficulties of traveling to a place when they know a group of earnest practitioners eagerly wants to learn and will practice what is taught. The group energy and collective karma draw teachers to this place.

In some of the Dharma centers I’ve visited, people say, “We come here, hear teachings or meditate, dedicate, and then leave. There’s not much exchange among people. It’s cold and unfriendly.” I feel sad when I visit those places, and so do the people there. Especially in our modern society where people are so cut off and alienated from each other, all of us seek a sense of community. We want and need many people—not just one person—to share our lives with. We need to put our energy into creating mutual Dharma give-and-take with others. It’s erroneous to think, “When I don’t come, no one in the group will miss me.” Actually, each person is important; a group is only a collection of individuals. We come together to give, not only to receive, from each other, and when we are absent, others miss our presence.

At the beginning of retreats, I often ask people to speak about why they came to the retreat, what they would like to receive from it, and what they would like to give. The last phrase often startles people. Seldom have they thought that they have something to give. Seldom have they considered that others can and do benefit from their presence. They don’t know that others miss their presence that contributes to the well-being of the group. It’s important to realize that we are mutually interdependent: our good energy helps others and theirs helps us.

Of course, this in no way diminishes the value of our individual practice. Having a stable daily meditation practice is worthwhile. Or, we may choose to set aside some time set each day when we sit quietly, get in touch with what is going on inside, or read a Dharma book in a relaxed and contemplative way. In addition to this, by being an interactive part of our Dharma community, we help build the full set of causes and conditions necessary for our personal practice to flourish, both now and in the future. We know that we are linked to others who understand and support us. We give our care and receive theirs.

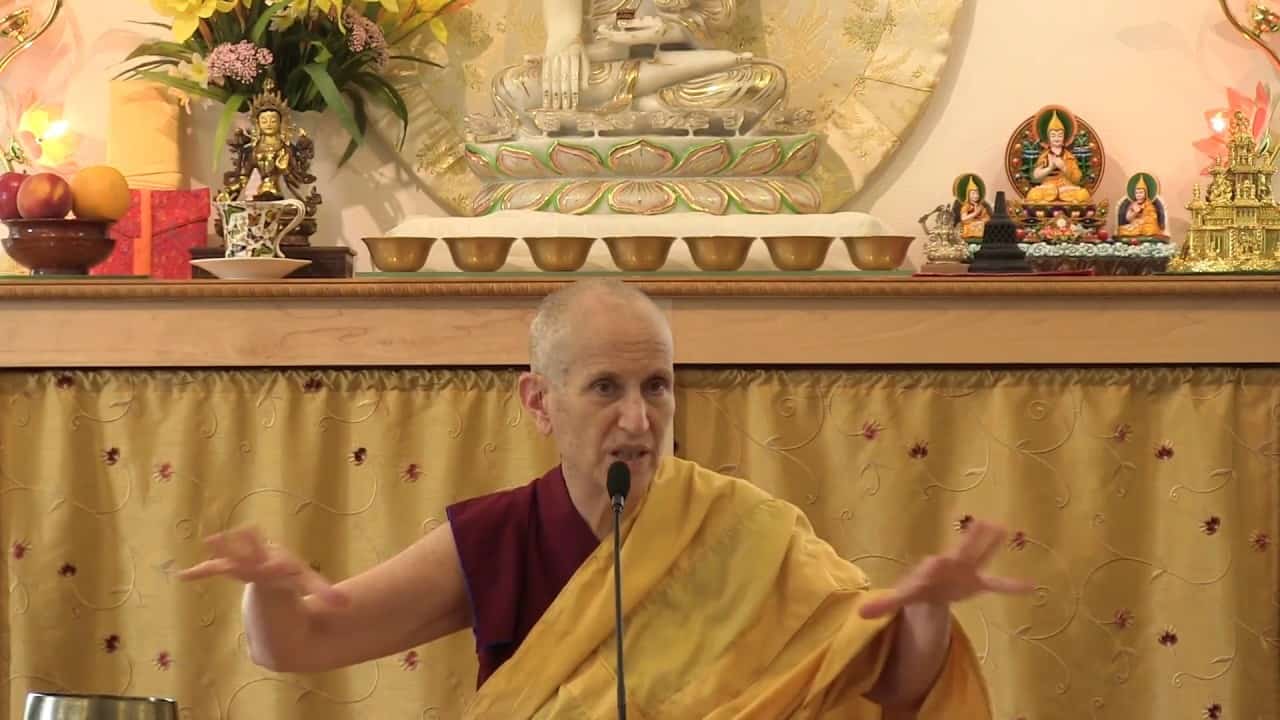

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.