Our precious human life

Part of a series of short talks on the 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas given during the winter retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- The first verse of the 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas

- The value of our human life for practicing the Dharma

Last week, when Venerable Chodron asked me if I would give the BBC three times a week during the retreat, I was kind of startled because I thought, “Wow, what will I think of to say so many times?” And then the thought arose, a sort of idea came up in my mind — maybe through the blessings of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas — to go through the text The 37 practices of bodhisattvas. So I could use that as a sort of framework. I did a quick calculation in my mind “Three times a week, four times a month” anyway, thirty-six times and it’s thirty-seven verses so it kind of works out really well. One verse extra will fit in somewhere along the way.

So what I plan to do is each time I give a BBC to do one verse. And realistically you know, to do justice to this text you need hours for each verse. We don’t have hours; I’m not gonna make you sit there for hours waiting for your lunch. Still, I thought it would be nice to spend just, you know, eight to ten minutes looking at each verse and I’ll share some thoughts, ideas that I have about it, and how to put it into practice and try to make it meaningful, especially in the context of retreat.

This first verse — I know many of you have memorized it, I haven’t gotten to that process I still have to read it — the first verse says:

Having gained this rare ship of freedom and fortune,

Hear, think and meditate unwaveringly night and day

In order to free yourself and others

From the ocean of cyclic existence –

This is the practice of bodhisattvas.

This verse is about the topic of the Precious Human Life which basically is about how fortunate we are to have a human life, not just a human life, but a human life with certain qualities — outer conditions as well as inner conditions — that make it the most ideal situation for engaging in the practice of Dharma. Then if we use our life in that way to practice the Dharma, we’re doing the most meaningful and beneficial thing we could do, both for ourselves and for others, and both for this life and our future life. That’s the basic idea of the Precious Human Life.

I’m sure all of you have heard teachings on it, and read about it, thought about it, meditated on it and probably some of you are so familiar with it that you know it backwards and forwards, and inside out, and upside down in every possible way. But then the question is:

“How much have we really deeply integrated the meaning of this topic in our lives?”

And sometimes it’s hard to know that. When things are going well, things are going smoothly in our life, we’re not facing too many difficulties, it can seem like, “Oh yeah, I’m doing really well, my practice is going really well”. But then, when we encounter a bump, some unwanted or unexpected experience which could be our health, some kind of health problem or it could be something inner, some emotional crisis happening or a crisis with a loved one, a family member, someone we are close to or with a job or whatever… So, when these bad things happen in our life: that’s an opportunity. We have to see how much we’ve really integrated this idea that we have a Precious Human Rebirth and the most meaningful thing we can do with it is to engage in practice of Dharma.

I’ve heard his Holiness the Dalai Lama say sometimes that there is a saying in Tibetan: “It’s easy to look like a good practitioner when your stomach is full and you’re sitting in the sun but when hard times come, that’s when you show your true colours.”

I’m paraphrasing it, I don’t remember the exact words but the basic idea is, “Oh things are going well” you know, you can look like you’re a good practitioner but then when the crunch comes, when difficulties come, that’s when you know, you can see well how true is that.

I’d like to share with you a story that for me was a great teaching on this topic of the Precious Human Rebirth. So back in 1987 a group of us went to Tibet for a pilgrimage — Venerable Chodron was along in that group — we were about twenty-five monastics (monks and nuns) and 15 lay peoples, and we were with my teacher Lama Zopa Rinpoche and another wonderful Lama Geshe Lama Konchog and various other Tibetans here and there. It was quite an extraordinary time. We traveled around in buses and visited different holy places, temples, monasteries and so on and did prayers and meditations and offerings and it was a real interesting experience. One day we were in Sera monastery — one of the big Gelugpa monasteries in Tibet — and these monasteries are a bit like towns you know, villages, they have many buildings and many houses. In the past they were filled with tens of thousands of monks. Now it’s different…

So we were there, we were visiting the various holy places and making offerings and so forth and we met a couple of monks who were residents of Sera monastery and they invited us for tea. I remember sitting in this room, this nice room… I think there were thangkas on the walls and carpets on the floor, so it’s sort of comfortable and cozy and we were drinking tea. And then Rinpoche asked these monks to talk about some of the experiences that they had, because these were monks who hadn’t escaped in 1959 along with the Dalai Lama and many other people. They had stayed all through the Holocaust — the Tibetan Holocaust — and experienced a lot of really horrible events and atrocities that were inflicted on the Tibetan people by the Chinese soldiers. So it was kind of strange to sit in this very comfortable cozy room and hear about these horrible stories.

One monk was sitting on a stool rather than on the floor and he explained that he couldn’t sit cross-legged because his kneecaps had been broken by Chinese soldiers hitting them with their rifle butts, and apparently that was something they did quite often to stop people from meditating.

Another monk was quite talkative. He told a number of stories. He said one of the things that the Chinese soldiers forced the monks to do was to go into town with buckets and collect human excrement. They had to knock on people’s doors and ask for excrement that they would then take back and put on the fields. So it seems this was a method designed to get the people to lose respect for the monks, to turn them into poo collectors rather than venerable members of the Sangha, and teachers and so on and so forth. And the same monk also said that at one point in time he’d been locked in a cell for eleven months, with his hands and feet shackled together. At the end, he said there were times when he thought he wouldn’t survive and he was so happy that he did survive and that he still had his precious human rebirth. That statement was just so powerful, it really made a big impact on me because I was kind of imagining how I would manage in that kind of situation, if I had to go through those experiences. I thought, “I don’t think I’d want to carry on living you know. I might become suicidal and just want to die”. So to go through those experiences and feel how fortunate I am to be still alive and have this human life, this precious human life, because it gives us the opportunity to engage in Dharma practice.

Also, I was really struck by the faces of these monks. Even though they’d been through these awful experiences, they didn’t show any signs of anger, or bitterness, or depression or despair. They actually looked kind of happy, smiling, and their eyes were sparkling. You could really see the value of engaging in Dharma practice. So for me, what that monk said symbolize the real meaning of the realization of the Precious Human Life. Even if we are going through difficulties in our lives — and I mean there are difficulties who are kind of unimaginable — so even in such difficult situations, difficult experiences, to still see that having a human life is valuable and not fall prey to despair, to depression, to hopelessness and so on but instead see, “Okay, I still have this human life, I still have this human body and mind, and I can use this life for things that are meaningful and beneficial.”

Even in such situations, even in prison, one can still creates virtue — once you know how of course, you have to know how to do that — but you can create virtue, you can generate compassion, loving kindness, wisdom, understanding the true nature of things. You can understand that soldiers and prison guards can lock you up physically but they can’t lock up your mind. Your mind is still yours and you have the control over your mind. You have the freedom to do what you want with your mind and there are lots of things that you can do with your mind if you know how to. You can do things with your mind to make sure that it goes in a positive direction rather than a negative one.

I think it could be helpful to keep this story in mind for the coming retreat, whether you’re here just for the weekend, for one month or the full three months. Because doing retreat, sometimes it can be blissful but sometimes it can be hard. It can be physically hard. You may have pain in your body — especially sitting so many hours — so there can be physical discomfort and suffering. Sometimes there can be mental suffering when our mind can be flooded with painful memories from the past, things that we have done or things others have done to us or whatever. Also just getting frustrated with this constant barrage of unwanted thoughts and emotions that just keep coming in our mind uncontrollably. Those are some of the things that people can experience during retreat. It’s not always wonderful and blissful but it’s important to remember that in spite of whatever difficulties we may experience, we’re still extremely fortunate to have this Precious Human Life, meaning that we have the opportunity to engage in meaningful and beneficial activities that benefit ourselves and others now and in the future. In fact, whatever difficulties we face — whether it’s in our practice or in our life — these are actually prime moments to engage in certain types of practice such as patience, such as thought transformation (Lojong), Tonglen and also purification. The Tibetans say that whenever we face difficulties, especially in the course of Dharma practice, this is a sign of purification. We are working out our bad karma. We’re decreasing the load or the “debts” of bad karma that we have. These are thoughts and practices that can help us deal with difficulties rather than become depressed about them.

It’s also helpful to remember impermanence; a very simple idea but just the fact that these problems we are going through are not permanent, they’re not going to last forever, they will pass. Also to remember that many other people have problems too and we are not the only one. Other people have the same kind of difficulty we’re having or similar ones. Some people have even worse problems, for example: even now there are people imprisoned in Tibet and going through horrific experiences like those we’ve heard about. And there are people in prisons in many other countries as well: China, Burma, Russia and of course right here in America. Thinking about others who have difficulties as well as ourselves helps us to focus less on “my problem” and open our heart with compassion and kindness for others. This is one of the best ways of generating compassion and it can also be a way to give ourselves a renewed burst of energy to work on ourselves so that we can be of greater benefit to other people. That’s what this verse is all about in the last couple of lines:

“In order to free yourself and others

From the ocean of cyclic existence –

This is the practice of Bodhisattvas.”

A Bodhisattva is actually someone who has uncontrived bodhichitta and that’s a pretty high realization. I’m not there, maybe some of you are but I’m an aspiring Bodhisattva. I aspire to be like the Bodhisattvas. You know, whatever we do with that idea, with that wish, to emulate the activities of a bodhisattva is so beneficial; it’s like a little child who aspires to be a doctor. He can’t immediately start practicing medicine but even in first grade, learning arithmetic, and reading and so forth it’s working gradually towards that day when he or she will be able to engage in actual medical practice. So it’s similar, that’s how I see myself: I’m an aspiring Bodhisattva, I’m like a little kid, a little baby hoping one day to be like the Bodhisattvas. Any effort we make in that direction, and we can each day of our life do things that will help us eventually become Bodhisattvas and then Buddha’s for the benefit of all beings

Thank you.

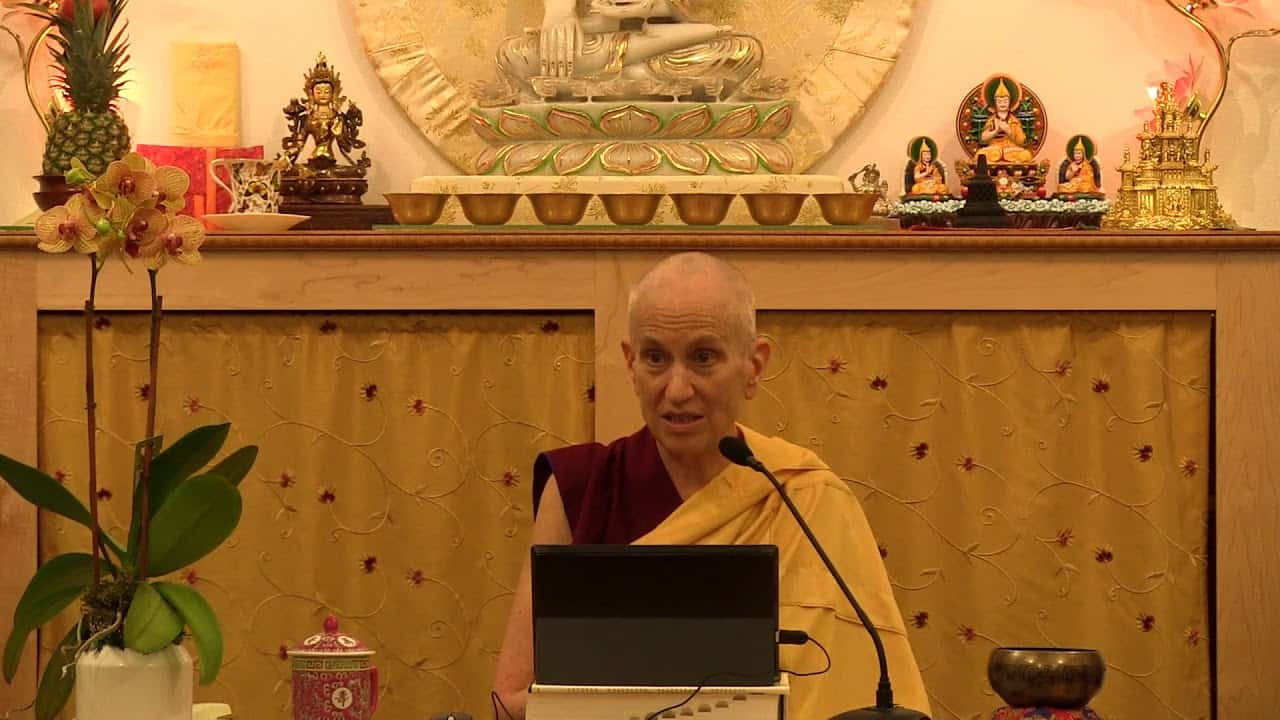

Venerable Sangye Khadro

California-born, Venerable Sangye Khadro ordained as a Buddhist nun at Kopan Monastery in 1974 and is a longtime friend and colleague of Abbey founder Venerable Thubten Chodron. She took bhikshuni (full) ordination in 1988. While studying at Nalanda Monastery in France in the 1980s, she helped to start the Dorje Pamo Nunnery, along with Venerable Chodron. Venerable Sangye Khadro has studied with many Buddhist masters including Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey, and Khensur Jampa Tegchok. At her teachers’ request, she began teaching in 1980 and has since taught in countries around the world, occasionally taking time off for personal retreats. She served as resident teacher in Buddha House, Australia, Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Singapore, and the FPMT centre in Denmark. From 2008-2015, she followed the Masters Program at the Lama Tsong Khapa Institute in Italy. Venerable has authored a number books found here, including the best-selling How to Meditate. She has taught at Sravasti Abbey since 2017 and is now a full-time resident.