Attachment, anger and confusion

Part of a series of short talks on the 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas given during the winter retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

- The second verse of the 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas

- How attachment, anger and confusion stirs us in all directions.

Some of you may not have been here last Friday. I gave the BBC talk Friday and explained that Venerable Chodron had asked me to give the BBC talks three times a week for the duration of this retreat. So I decided to use the text The 37 practices of Bodhisattvas and do one verse each week or each talk, each BBC. So last week I did the first verse about Precious Human Rebirth and the importance of using our precious life to learn and practice the Dharma to the best of our ability and to do this for the purpose of freeing ourselves and others from the ocean of cyclic existence.

Attached to your loved ones you’re stirred up like water.

Hating your enemies you burn like fire.

In the darkness of confusion you forget what to adopt and discard.

Give up your homeland –

This is the practice of bodhisattvas.

The second verse goes on to talk about the three poisons. To be free of cyclic existence, this is the main thing we have to do, it is to free ourselves from these three poisonous states of mind which are: attachment, ignorance and aversion or hatred or anger. I was thinking yesterday, venerable Chonyi spoke about The Three Principal Aspects of the Path and there’s kind of a rough correlation between those two groups of three. The first principle of renunciation (or the determination to be free) there counteracts attachment. The second one, bodhichitta, counteracts anger, hatred, aversion. The third one, correct view, counteracts ignorance…(Roughly).

In the first line he says, “Attached to your loved ones your stirred up like water” and I was intrigued by that image and what came to my mind was hurricanes. Sometimes water is calm and quiet and gentle but then, because of strong wind or earthquakes like happened recently in Indonesia then the water can get stirred up and have tremendous power, even to cause death and destruction. It’s kind of similar with attachment. Sometimes in our relationships with the people that we have attachment to, things can be kind of smooth and calm and gentle and sweet but then problems can arise. For example if this person doesn’t do what we want them to do or they do something we don’t want them to do; we don’t get our way, then the second poison comes out: the fire of anger. I think attachment often — if not always — leads to anger. If we look at situations where we’re angry, we might be able to see behind that or underneath that is attachment. So the more attachment we have the more chances there are of anger and quarrels in relationships. Even if that doesn’t happen, I mean they’re maybe couples or people in relationships who don’t get into fights so much. I once met a couple in Australia who were in their 80s or 90s and they said they’d never had a fight in their life (for 60 years). I find it hard to believe but it may be true, it’s possible that people don’t fight too much, but even in that kind of relationship there’s eventually the problem of loss one of the two people will pass away and leave the other one behind. That always happens with relationships: they always come to an end and when that happens then there’s another kind of storm, floods of tears and heart-wrenching pain. This is probably one of the most painful experiences that human beings have: losing a loved one, especially someone you’ve been together with for decades.

So it seems that attachment inevitably leads to suffering. Attachment in relationship; there’s always going to be some suffering that will come. So the solution isn’t to cut ourselves off from everybody and live alone like a hermit, although some people do that, but it’s not for everybody. Instead what we can do is work on decreasing our attachment and increasing loving-kindness, unconditional love and kindness, compassion. In that way, the relationship will be healthier and there will be fewer problems. I think one of the best antidotes to attachment is reflecting on impermanence and death. It’s not a very pleasant subject but it’s really really helpful really really powerful. The more we can get used to the idea that our loved ones are not going to be there forever then when that does happen, when we do separate from them, it’ll be less traumatic, less painful. Then increasing the love and the compassion will make the relationship much more healthy and satisfying for everybody and we’ll have fewer problems. So there’s lots of methods in the Dharma for how we can decrease attachment.

And then the second line deals with anger and I don’t think that needs too much explanation; I think we all know how painful it is to have anger and hatred and it is like fire: it’s really really really painful. There’s lots of methods, Dharma methods, there’s whole books full of methods for working with anger, such as Venerable’s book called Working with anger and there’s one by His Holiness called Healing anger. So lots of methods, so when you notice anger arising in your mind, don’t get angry at yourself and beat yourself up for being angry; it’s just a normal human experience, it’s part of samsara. Be kind to yourself but then work on it, find some remedy and again: loving-kindness and compassion are great remedies because you can’t have both at the same time, at the same moment towards the person you can’t have both anger and love. So the more we can have love, kindness, compassion, patience, those positive qualities, the less space there is in the mind for anger to arise.

And then the third line deals with confusion. The word confusion is often used interchangeably with ignorance. Ignorance and confusion are pretty much the same thing and when we hear about ignorance or confusion, we probably first think of ignorance about the true nature of things, ignorance about emptiness. Here he seems to be talking about another kind of ignorance. There are different kinds of ignorance and one of these is ignorance of karma: what is positive, what is negative, what is virtuous, what is non virtuous. So he’s saying here that, when our mind gets lost in the confusion of ignorance or the darkness of ignorance, then we forget what to adopt and discard. This phrase “adopt and discard” comes a lot in the teachings and it’s basically talking about: there are certain things we need to do, to practice, to engage in; other things we need to give up. One of the first things we need to do on the path is with regard to virtue and non virtue, to refrain from (or discard) what is non virtuous (like the ten non-virtuous actions: killing, stealing and so on) and to adopt (or practice) what is virtuous (such as refraining from killing, refraining from stealing and also on).

On top of that we can also do the opposite kind of actions like saving lives, protecting lives, giving, being generous. There’s lots of ways we can create virtue. Even if we know this intellectually, intellectually we know what we should do and shouldn’t do but sometimes our mind gets confused and we forget and we slip back into our old habits. One reason this can happen is when we’re in the company of other people (some of our family members, some of our friends) who are not interested in doing this, who aren’t interested in working on their minds and practicing virtue and giving up non-virtue. We are so easily influenced by other people, the people we live with, the people we spend time with, like that saying: “monkey-see monkey-do”.

And there’s also the factor of wanting to be accepted, to be liked, wanting to be seen as cool and not as weird. These are some of the factors that make it hard for us to continue practicing what we wish to practice in certain company. That’s why the fourth line says: “Give up your homeland”.

Homeland doesn’t necessarily mean the whole country, but it could mean your family, your community, your usual circle of friends. Again, if those people (or some of those people) are not concerned about working on their minds, about doing what’s virtuous and refraining from what’s non-virtuous, then we may find it difficult to practice when we’re in their company. That’s why some people decide to move to a place like the abbey or other monasteries or retreat centers or communities where it’s more conducive for practice. You’re living amongst people who are really dedicated to trying to practice the Dharma, to live a wholesome life, so it’s much easier in this kind of situation (as I’m sure you all know). Not everybody can completely move, leave home and move to a place like this but at least you can come here from time to time, (which I don’t think I need to tell you that, that’s why you’re here!) come for retreats and spend some time in such a situation and get a boost. This gives you a kind of boost to your practice so that when you do go home, you’ll be able to practice better, you have more strength in your practice. You might even be able to have a positive influence on the people at home, your family and friends. Not preaching to them (I certainly don’t advocate that, that’s not at all a Buddhist thing to do) but just by being an example.

Another saying I always like is: “actions speak louder than words”. I really feel that’s true. As Gandhi says (I love this one): “Be the change that you want to see in the world”. So, if you yourself are trying to be more kind and compassionate, less angry, less caught up in the three poisons and try to be more virtuous and less non-virtuous; you might be able to influence the people around you, just a little bit more.

It’s possible that some people might misinterpret this advice about giving up your homeland and think that that’s the problem: “it’s my home, it’s my family, those horrible people you know, and I need to get away from them and then everything will be okay I won’t have any more problems”. Not true unfortunately… We know that, even if we come to a place like the Abbey or even if you go to a hut in a remote area and you’re staying all by yourself, these poisons will still be coming up in your mind. The problem is in here [Ven. Khadro points her fingers towards her heart]. We take the mental poisons with us wherever we go so the only way to really be free from these poisonous states of mind is by confronting them and working on them. Again, there’s lots of tools for that but we also need a lot of patience; it does take time and persistence. Just keep working at it and slowly, slowly, slowly, you’ll see them decrease. Do this with a lot of kindness and compassion with yourself, not beating yourself up. I’m sure you’ve heard that before but it doesn’t hurt to hear it again.

Then we could take this advice to mean not completely cutting yourself off from your family and never seeing them again but take breaks. Come to places like the abbey, come to retreats and get a strong dose of practice and then go back and try to keep practicing in that situation. Be really careful not to blame your family and other people for your problems and have feelings of aversion and resentment. You probably know that, but it’s possible that some people might use this kind of advice to justify such feelings and cut themselves off from their family, but this would be for the wrong reasons.

One of my early teachers, Lama Yeshe, once said that if we have any unresolved problems with our parents we will not be able to make progress in our spiritual practice. That really affected me because most of my life I had problems with my parents. I thought, “oh, I need to get away from these people, they are so difficult”. That motivated me to really work hard on my mind, my attitudes, my relationship with my parents and I think the same applies with any other important people in our life: siblings, aunts, uncles, grandparents, friends and so forth. We really need to work on clearing up any unresolved problems in our relationships because otherwise, if they pass away or we pass away before those problems have been cleared up, then it would be quite sad, we’d feel a lot of regret. I’m really grateful to that advice from Lama Yeshe because I was able to clear up the problems with my parents before they passed away and really feel love and appreciation for them. So please don’t misunderstand this verse, it doesn’t mean leaving home with aversion and resentment and so on, but it’s to help yourself in your practice so you can overcome these poisonous states of mind and then be able to have healthier relationships with them and help them to likewise overcome these states of mind.

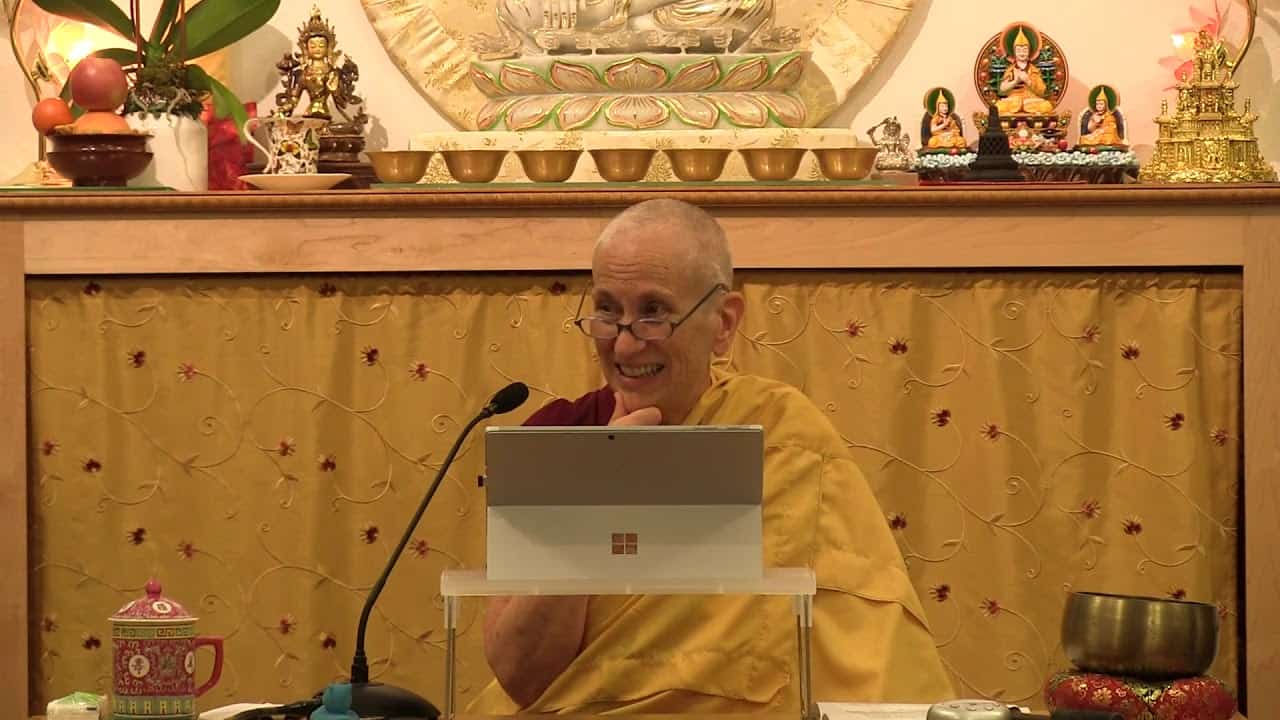

Venerable Sangye Khadro

California-born, Venerable Sangye Khadro ordained as a Buddhist nun at Kopan Monastery in 1974 and is a longtime friend and colleague of Abbey founder Venerable Thubten Chodron. She took bhikshuni (full) ordination in 1988. While studying at Nalanda Monastery in France in the 1980s, she helped to start the Dorje Pamo Nunnery, along with Venerable Chodron. Venerable Sangye Khadro has studied with many Buddhist masters including Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey, and Khensur Jampa Tegchok. At her teachers’ request, she began teaching in 1980 and has since taught in countries around the world, occasionally taking time off for personal retreats. She served as resident teacher in Buddha House, Australia, Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Singapore, and the FPMT centre in Denmark. From 2008-2015, she followed the Masters Program at the Lama Tsong Khapa Institute in Italy. Venerable has authored a number books found here, including the best-selling How to Meditate. She has taught at Sravasti Abbey since 2017 and is now a full-time resident.