Being an example of compassion

Part of a series of short talks on the pithy verses from the end of Lama Yeshe's book When the Chocolate Runs Out.

- Having a genuinely compassionate motivation

- Practicing with those imemediately surrounding us

- What suffering is: three kinds of suffering

We’re still talking about Lama Yeshe’s pithy instructions here.

Live in harmony with one another

and be an example of

peace, love, compassion, and wisdom.

We talked about the first part. We’re going to talk about being an example of compassion.

Like I said before, if we have the thought, “I’m going to be the example of compassion,” then we’re kind of creating an image and getting attached to it, and “I want everybody to see me as a compassionate person, whether I really am or not.” So it’s best not to try to be an example of compassion, but simply to be an example of compassion. In other words, to have a genuinely compassionate motivation, and to act with that.

As we always stress, we have to practice love, compassion, all these things, with the people immediately surrounding us, and then to extend it, because it’s so easy having compassion for people on the other side of the planet, whom we don’t have to interact with. Who don’t bug us. But having compassion for the people who don’t share our same political opinions, who have different values, who don’t have the same kind of manners as we have, or (don’t) come from the same culture so they think differently, or they have different habits, or whatever. On the basis of all these kinds of simple differences then we can get quite irritated with other people, and start considering them “other.” This is, unfortunately, what’s happening in the country, and why I think it’s so important to keep coming back to “but we all want happiness and none of us want suffering,” and simply on that basis alone to to wish others to be free of suffering and its causes, which is the definition of what compassion is.

Now, wishing others to be free of suffering and its causes also raises the issue of exactly what is suffering and what are the causes of suffering, and we often don’t think deeply about this. We simply go to the level of suffering that all beings don’t like, which is the very gross kind of physical or mental suffering. That suffering hurts, and we all don’t like it, and our foundation is to wish others and ourselves to be free of that level of suffering. But that isn’t quite sufficient because there are a lot of other different kinds of suffering. If we only focus on the “ouch” kind of suffering then we only have compassion for certain living beings, and we tend to then blame other living beings who we see as the ones who perpetrate the suffering of the ones we have compassion for. So we’re still left with a mind of “us and them”, and “good guys and bad guys”, and “victims and perpetrators”. And that kind of mind doesn’t work so well if you really want to practice the bodhisattva path.

We often talk about three levels of suffering, or of dukkha. The “ouch” kind of suffering is one. The second is the suffering of change, meaning the whatever pleasure we have, whatever happiness we have in cyclic existence doesn’t last, and whatever we do that brings that pleasure, if we do it long enough it turns into gross kind of suffering. If we really contemplate that level of dukkha and see how we suffer from it as well, then that opens our mind to have compassion also for people who are famous, who are rich, who see to have every samsaris happiness that is available. And to see that those people, too, have a life that is unsatisfactory.

This is very important, because otherwise our compassion really becomes quite lopsided. Compassion for people living the ghetto, but hatred for the people living in Beverly Hills. Or the South Hill, here in Spokane, would be South Hill. But that covers over the fact that even the people who seem to have everything are not completely satisfied in their lives, and that nobody, including them, escapes from aging, sickness, and death.

Which leads us to the third level of dukkha, which is being under the control of afflictions and karma. All of us, whether we are experiencing happiness or misery at this particular moment, we still experience that level of dukkha, under the control of afflictions and karma. It’s very important to realize that. Just getting wealth, just being popular, just having power, or getting everybody to do what you want them to do (which isn’t possible anyway), but even if we could, even that is not really what true happiness and fulfillment are. And so to see that the people who experience the dukkha of change also have suffering, and we’re all stuck in the same boat of samsara, which experiences the third kind of dukkha of pervasive suffering.

To go back to the dukkha of change, and I think this is what is very important if we can see in our country right now, because there seems to be so much blaming of other people. “I suffer because of what you do”. But to recognize that even the rich and the famous and the wealthy have a lot of problems is very important. And they may have a totally different kind of problem than the people who are in poverty, but it’s still problems.

For example, the rich (and famous and so on) are often so busy working that they have very little time to spend with their families and their kids, and as a result the kids sometimes start acting out because they feel quite neglected, and the only support they get from their parents is this pushing to score well in your school, and score well in your university entry exams, and to be a success according to what the parents want you to be. Then those kids often have a great deal of mental suffering. They rebel. Or—there was an article in the paper some time ago—some of them commit suicide because of the pressure their family puts on them. Then the parents feel incredible grief over abusing their children. That’s a whole other kind of suffering. Or the suffering of what happens when you are a big basketball or football player, and then you get old and you can’t do your sport anymore, and your whole body is falling apart. Then you have not only the suffering of the body that everybody experiences, but the suffering of trying to change your self-image from being somebody who is healthy and strong and athletic, to somebody who now depends on other people. And that’s a lot of mental suffering.

The suffering of people who are wealthy when they lose their money because the economy goes down. Or there’s a revolution in their country, or an uprising in their country and they have to flee for their lives because either the government has turned against them or the population has turned against them.

They always say be careful who you’re jealous of because you might someday be like them and then you experience the kind of suffering they experience.

Then, of course, compassion for those who have what we all share, which is that we are not free, and we are subject to birth, aging, sickness, and death. And it really doesn’t matter if you die in a really gorgeous hospital with starched white sheets folded with hospital corners and all the latest medical equipment, or you die in the streets, because when we die we die alone. It doesn’t matter how many people are surrounding you, death is a solitary experience. And material wealth doesn’t help at that time. And the people surrounding you saying how much they love you, that doesn’t help at that time either. Just see that this is an experience that we all go through. Nobody’s immune from it. Then to open our hearts in compassion for all sentient beings, who experience birth, aging, sickness, and death. Then who experience rebirth, aging, sickness, and death, and again rebirth, aging, sickness, and death, ad infinitum, with no cessation in view, unless they happen to encounter the Dharma in their samsaric wandering.

Then, of course, it’s the compassion, when you see people who have encountered the Dharma, and then who get distracted from it. Or who encounter the Dharma, and then say oh, it’s irrelevant.

I worked at the office in Kopan, and people would come up the hill looking for a spiritual path, and then as soon as one of the teachers started talking about the eight worldly concerns, it was like, “I’m out of here, this is irrelevant, I want to go have a good time.”

People encountering the Dharma. Then also, because of whatever, getting angry at the Dharma, getting jealous of the Dharma, getting angry at their spiritual mentors, for who know what kind of reason, and then just walking out on everything, and saying, this is.bunch of hooey.

Or people who have faith, and like I said, get distracted from practice. They could be practicing, but hey, I want to take care of this, and that, and the other thing. That’s something to really have compassion for those people, because they’re so close and they’re so far away.

Anyway, to be an example of compassion means first changing our own mind to have compassion, then extending that to the people around us and to all sentient beings.

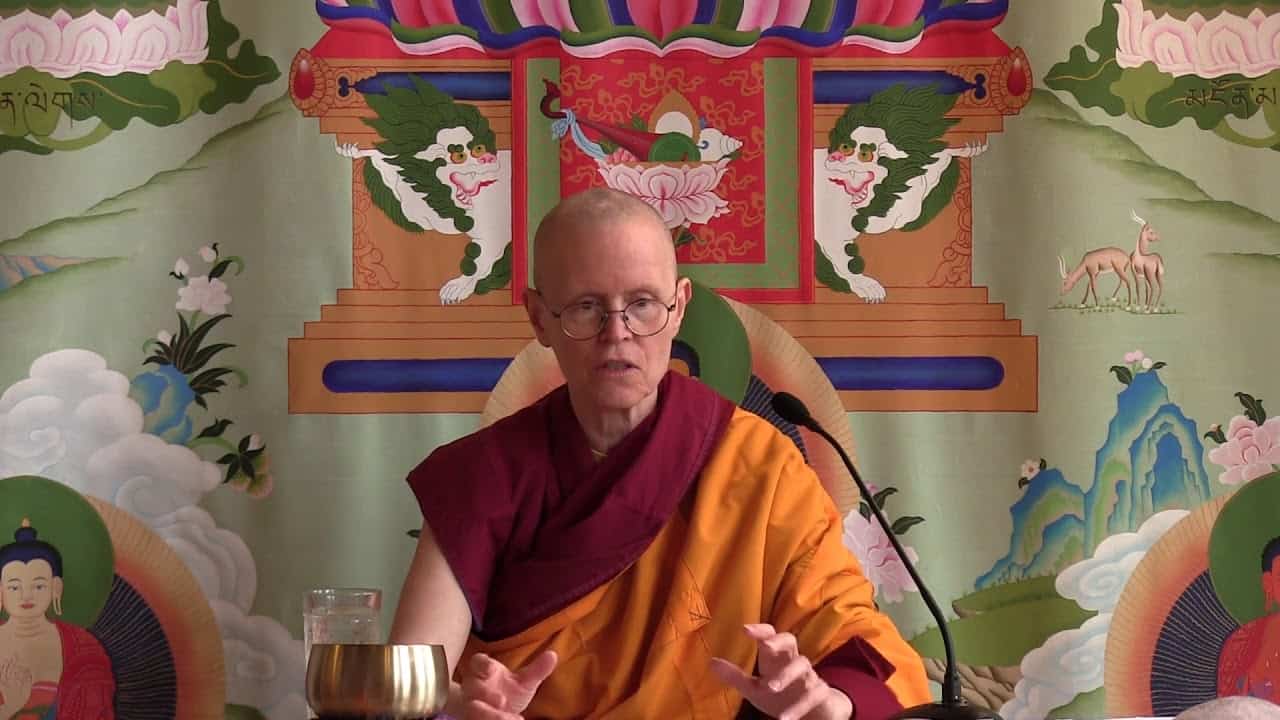

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.