Introduction to breathing meditation

Part of a series of teachings given during the Developing Meditative Concentration Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2016.

- Guided breath meditation

- Responding to disturbances

- Overview of the retreat

- How to do the walking meditation session

- Refuge and precepts

- Concentration meditation in context

- The wisdoms of hearing, thinking, and meditating

- The foundation of ethical conduct

- Purification

- Meditation posture

Sit with your back straight and your hands with the back of your right hand on the palm of the left, the thumbs touching. Have your hands in your lap. And then to begin the body relaxation, just focus on feeling your body sitting here on the cushion or on the chair. In other words, bring your mind, your attention, to where your body is and what you’re about to do now.

Then become aware of sensations in your legs and your feet. If there is any tension there then let that go. Be aware of the sensations in your belly and your lower abdomen. If you’re someone who stores their attention in their belly, so your belly is tight, then try and let that relax. Be aware of the various sensations in your back, shoulders, chest and arms. If your shoulders are tight, especially from working on the computer, try lifting them up to your ears as high as you can, tucking your chin in, holding your shoulders up like that for a moment and then quickly dropping and moving them. That can be very good for releasing tension in the shoulders.

Then become aware of sensations in your neck, head, face and jaw. If your jaw is clenched then let that relax. If your forehead is furrowed and you have creases between your eyebrows because you think that will help you concentrate better, try and let that go as well. Then come back to feeling your whole body, but this time be aware that it’s very firm. The position of the body is firm, but it’s also at ease. The tension is gone. Just as your body can be firm and yet at ease, your mind can also be firm and attentive but at ease and relaxed.

Now we will move into the breathing meditation itself, so place your attention either at the belly and watch the rise and fall of the belly, or at the nostrils and upper lip and watch the sensations of the breath as it flows in and out. Don’t go back and forth between those places; pick one place and keep your attention there. If you get distracted by a thought or a sound or a physical sensation, simply note that and then return to the breath. Don’t make a story about your distraction. Just note it and come back to the breath. We’ll have some time of silence to do that.

Setting our motivation

Then before the talk, we’ll cultivate our motivation. So again, let’s have a very big mind, a very large motivation encompassing all living beings and wanting to benefit them. Let’s not leave anybody out. And let’s remember that we want to benefit sentient beings not only in this life with things that may bring them happiness in this life, but to benefit them especially by being able to share with them the happiness that comes from Dharma practice, from freeing the mind from ignorance, anger and attachment, from freeing the mind from self-centeredness. And so with that long term motivation, we’ll participate in the retreat this weekend.

The format of the retreat

I first wanted to go over the format a little bit. You’ll notice that we have a session in the morning and the afternoon. These are teaching sessions that also include meditation. Then we have another meditation session before lunch, and there will be some chanting during that meditation session. The Abbey does some Chinese chanting that is very beautiful. First we bow to the Buddha and then we do a refuge chant taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. Those help to prepare the mind for meditation. We’ll do that first and then sit down for seated meditation the rest of the period.

And then after eating isn’t always the best time for meditation, so we’ll have a session after lunch that combines walking and seated meditation. We’ll do it outdoors; hopefully the weather will hold. What we do is we alternate fifteen minutes of walking with fifteen minutes of seated meditation, and there will be three different groups walking at three different speeds. When the bell is rung, you sit down where you are. Hopefully, it will be dry; if not, you can head for a chair somewhere.

At the time of the Buddha, people meditated outdoors. The Sangha would have their meal, and they would go into a park and meditate in the afternoon. There were sounds from animals and different things, and you were out in nature and felt the wind and the sun, but that was all part of one’s meditation practice. You accepted what was around you. Nowadays, sometimes we think, “I’m meditating, so everybody needs to be totally quiet—no cars, don’t move. I’ve got to go somewhere it’s just absolutely silent.”

But when you do that, you find out that your mind is actually very noisy and that the distraction is not so much from the outside as it is from inside. We have to learn to deal with these different distractions. It’s very quiet up here. People say they don’t sleep so well up here because it’s so quiet. They aren’t used to that quiet. But you’ll hear a car or the turkeys. You might hear a person or different things. Instead of having the mind react with, “Why don’t you shut up and stop disturbing my samadhi,” train your mind to say, “Oh, there are some living beings who are doing what living beings do, and I wish them well.”

If it’s somebody going somewhere: “May they be safe.” If it’s somebody talking: “May they communicate kindness to each other.” Instead of seeing the environment as something that is disturbing your “precious meditation practice,” have a mind that welcomes sentient beings. But you don’t start thinking about them. You don’t think, “Where are they going?” You don’t think, “What kind of motorcycle are they driving?” Just wish them well and then come back to your meditation.

Different meditation traditions

I wanted to talk a little bit about the walking meditation that we will do. There will be three groups and each one of them will be led by different Sangha members who will tell you, at the end of the next session, where to meet their particular group. We do it this way because in Buddhist traditions there are different ways to do walking meditation. It’s really quite interesting. There are different ways of doing eating meditation, too.

There’s one tradition mostly followed in China and Korea where the walking meditation is done very briskly, very quickly. You walk at a very quick pace to energize the body. So, typically, you’re walking around some holy objects so that you accumulate merit at the same time that you are invigorating your physical energy, which is especially good if you have trouble with drowsiness.

Here at the Abbey, you’ll be walking at a brisk pace, and it will be around the garden, around Gotami house, up along the road and then down here around Chenrezig and back into the garden. It’s follow the leader so you don’t get lost, and you keep the pace of the person who is leading. You hold your hands right on the left, just like when you’re meditating, at your waist. You walk like that, or if you’re walking briskly, you may also swing your arms; that’s okay. Then there will be a group that walks at a more medium tempo, and that group will just go probably just around Ananda and the garden. Again, you’re holding your hands with right over left at your waist. And then there will be a slow group that will walk just around the Buddha at the center of the garden. That group walks very slowly.

The slow group will start out at a regular pace and then slow down. With the very slow group, at first you’re watching right and left, right and left, and then as you slow down, you become more aware of different passages with your foot: lifting, pushing, placing, lifting, pushing, placing. I think it’s also quite interesting to be aware of the dependent nature of your feet—and this goes for all three groups. Be aware of how your feet depend on each other and how your weight shifts from one foot to the next: one foot alone cannot walk. You can only hop on one foot. If you have one foot you have a crutch or a cane because you need to balance, and the legs are having to cooperate with each other.

I often see that as a metaphor for people cooperating with each other because you can’t have one leg that tells the other to be quiet and do it my way. They work together, and each has its own role. They depend on each other. So, that’s what to focus on for the slow group.

For the middle tempo group, it’s helpful to imagine either a small Buddha made of light at your heart—your heart chakra, not where your physical heart is. You imagine the Buddha at your chest center. So, you can do that or you can imagine a small Buddha made of light on the top of your head and imagine the Buddha radiating light to the surroundings, purifying and pacifying everything and all the minds of all the beings in the environment. Imagine this as you walk, and you can even recite the mantra while walking: Teyata om muni muni mahamuni svaha.

You can do that, or again, you can be aware of the dependent nature of your feet as you’re walking and also of the impermanent nature of walking. If you really get into it, it depends on how fast you’re going and how much attention you have to pay to where your feet are going, but you can also contemplate, “What is walking?” So, what is walking: see if you can come up with what is walking. And a second question is, “Who is walking?” We say, “I’m walking,” but who is the “I” that is walking? What is the agent that is doing the walking? It’s the body. The body is walking, but I say, “I’m walking.” Why do I say, “I’m walking,” when the body is walking? What’s the relationship between the “I” and the body?

This is also an interesting one to contemplate during your walking meditation. Those are just some suggestions for you to reflect on so that you can bring the contemplation of impermanence, dependent nature, and selflessness into your walking meditation.

Why we take refuge

Then we’ll come back here for the afternoon session, and the rest of the day gets completed with evening meditation. We’ll do that today and tomorrow. Then Monday morning there will be an initial talk and then some people have requested to take refuge and precepts, so that will also be done Monday morning. I won’t talk so much about that right now, but at the Q & A sessions this afternoon and tomorrow, you can bring it up.

I’ll just give a little sketch of it. Refuge is when you are deciding that the spiritual path you want to follow is the one taught by the Buddha. So, you’re clear about the path you want to follow; you’ve researched it; you have confidence in it. You’ve been practicing, so you’re really ready to say in the presence of the visualized buddhas and bodhisattvas and the preceptor, that you are choosing to follow this path. It’s like, “I’m done switching practices: Monday night crystals, Tuesday night Hare Krishna, Wednesday night Rosicrucians, Thursday night Kabbalah, Friday night Sufi dancing, Saturday night something else, and Sunday morning church.” [laughter]

You’ve decided that you’re tired of switching practices; you’ve done that, and you’re ready to settle on something. So, it’s making a commitment to follow the Buddhist path, and as part of that, we’re opening ourselves up to following the advice of the Buddha. And the first advice the Buddha gives us, to put it in colloquial language, is to “stop being a jerk.” As we discussed last night, what are the jerk-like actions that we find in society that cause the most trouble, that wind up on the front page? It’s killing, stealing, unwise and unkind sexual behavior, lying and intoxicants. So, you have the choice when you take refuge to take some or all of those precepts. The people in the afternoon will go more into detail about the precepts, but taking them is a very good way to get clear in your own mind what your own ethical standards are and what you will do and won’t do.

And then when you meet situations in which you’re feeling tempted to do something or people are pressuring you to do something, then instead of getting confused, you step back in your mind and say, “Well, I’ve already thought about that and decided I don’t want to do those kinds of behaviors. So, there’s no reason to get confused. I just explain to the people that “Sorry, I’m not going to do that, and that’s it.” Things become much clearer for you. Taking refuge and precepts is entirely optional; there’s absolutely no pressure with this. If you’re not sure, it’s better to wait. But that ceremony will also be done on Monday morning. So, that’s an overview of what we’ll be doing.

Also, a friend of ours wrote in calligraphy the homage to Candrakirti’s text The Supplement to the Middle Way, which is a commentary to Nagarjuna’s text The Treatise on the Middle Way, which is a commentary on the Buddhist teachings on emptiness. Candrakirti’s Homage to Great Compassion is a very famous verse full of meaning. We could have a whole retreat just about that verse. So, this person very kindly did it in calligraphy and framed it, and then John kindly drove it up here, and so it will be hung in the foyer where Kuan Yin is when you enter Chenrezig Hall. At some point after it’s hung, for those interested, I think it would be nice if we all gather there and recite the Homage to Great Compassion three times.

It’s an homage to compassion, which is quite powerful, but it needs a lot of unpacking. It’s one of those things where each word has a lot of meaning. But I think that would be a very good way to welcome this to the Abbey. I was thinking that it’s quite strange that Tibetans have this thing where when you have a new statue, you do a consecration of the statue to invoke the buddhas into the statue. But when you have a new text they don’t do a consecration ceremony. I was thinking it would seem that you should in the same way because you’re still invoking the wisdom of the buddhas into the object, but for some reason they don’t. But we’ll read The Homage to Great Compassion together three times.

Concentration in context

So, that’s the layout of the weekend. I also wanted to go over the details for the meditation. We’ll be doing different kinds of meditation this weekend—not too many different ones, but enough so that you can get some kind of hint of how to develop concentration. But I want to place developing concentration and meditating in general in context. In the West now, you read about meditation in Time Magazine, and mindfulness is the latest buzz word, and a lot of this has been taken out of context to secularize it. That has its benefits, but I think it’s good if you do secularized meditation or secularized mindfulness to realize what it is and that it’s different from Buddhist meditation and Buddhist mindfulness.

I think it’s quite important to differentiate them because it’s quite interesting to watch how Buddhism comes to America. If you have the opportunity to go to Asia and live with an Asian Buddhist community, you see that the Dharma is just fully integrated into their lives. And the people are Buddhists and they have refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. They don’t just meditate. They do lots of different things because Buddhist practice consists of lots of different things. It’s not just meditation.

Some of the first people who brought meditation to the states were the people from the Insight Meditation Society, and what they did is that they brought one type of vipassana meditation. There are many types of vipassana meditation, but they brought one type of meditation back to America, and they didn’t bring the whole context back in which you do vipassana meditation. In Asia, Vipassana meditation is done in the context of having an awareness that we are beings who are trapped by our own ignorance, anger and attachment, that we are born in cyclic existence again and again under the influence of these disturbing attitudes and wrong views and disturbing emotions, and also the karma, the actions, that we do. So, that whole Buddhist worldview is like the water surrounding the fish of meditation.

I find it interesting when meditation is taken out of its environment like that and just taught as more of a psychological technique. The result of your meditation is going to be different because the result of your meditation depends on your philosophical beliefs, your philosophical training, your worldview. I read about one man who was doing Zen meditation, and it was taken out of the context of how it is done in Asia, and at the end of the retreat he decided he believed in God. So, you can see that if you don’t do the meditation within the context of the Buddhist worldview, you’re going to get a totally different result. [laughter]

We’re doing it within the context of the Buddhist worldview, and when you are a practicing Buddhist, you don’t just meditate. The Buddha didn’t teach just meditation. When he spoke of wisdom, he taught three kinds of wisdom: the wisdom of learning, the wisdom of contemplating, and the wisdom of meditating. So, first you have to learn the worldview; you have to learn what meditation is, what the objects of different kinds of meditation are—you have to learn all these kinds of things. Because if you don’t learn, then what are going to meditate on?

If you don’t learn then you’re going to wind up being like me at the first meditation course I went to. This was back in 1975. I had hair down to my waist, big earrings, a peasant skirt and blouse, and I walked into my first meditation course that was a three week course offered in the Summer. I was a teacher, so I wasn’t working in the summer and could go. I went and sat down, and in the front of the room there was a western woman with a shaved head and a western man wearing a skirt. [laughter] It was being taught by two Tibetan lamas, and they said, “The Lamas are a little bit late, so we’re going to meditate while we wait.” Not having studied or learned anything, I had no idea what to do. But I remembered seeing a picture in a magazine of somebody sitting in a certain posture with their eyes back in their head and their mouth kind of hanging open, so I tried sitting like that because I didn’t have any idea what I was doing, but I didn’t want to look like I didn’t know what I was doing.

I still looked like I didn’t know what I was doing. [laughter] Thank goodness, the lamas came very quickly because I think I would have gotten a severe headache with my eyes rolled back in their sockets. [laughter] And I had no idea what to do with my mind. I had an idea of what to do with the body but no idea what to do with my mind when you meditate. So, we have to learn. We have to learn not just about meditation but about ourselves: what is this world we live in, particularly our inner world? What is this body really? What is our mind? What are our feelings? What are our emotions? What are our views?

We have to learn about who we are so that we can get an idea of who we aren’t. And I say that because we all want to discover who we really are, and Buddhism teaches us who we really aren’t. But we have to learn, so we need to listen to the teachings and study the teachings. That’s wisdom from study or listening or reading or whatever, and here I must make a comment, too: if you confine your study simply to reading then you are losing out on having a personal connection with a teacher. While the internet is very good for allowing people to hear teachings from a distance, I think you also have to complement that with coming to a retreat and going to live teachings. Because it’s a totally different experience when you hear teachings orally and you’re sitting there with a group of people rather than in your comfy chair with your coffee cup and your feet up watching something on the internet.

I think that’s something that is quite important on the path actually. So, you learn and then you contemplate or think about, reflect on, the teachings—all those refer to the same activity of really thinking about what you’ve learned. Here the Buddha really stressed the importance of investigating the teachings and contemplating them: do they make sense? Do they work logically? If I practice them, what happens? It’s not just a thing of, “Sign me up; I believe,” it’s more like, “What does this really mean? How does that work? How does that fit together with the previous teachings I’ve heard?” That’s the second wisdom.

Ethical conduct and meditation

The third wisdom is from meditating, from really integrating the teachings within our body and mind. In a full Buddhist practice, we want to do all three: hearing, thinking and meditating. We don’t want to do just one and leave out the other two because they really fit together. They help each other. Also, it’s important to develop our meditation and concentration on the basis of ethical conduct. Last night I mentioned briefly the three higher trainings in ethical conduct, concentration and wisdom. Ethical conduct is the basis for this, and there are certain mental factors that we cultivate in ethical conduct that set the stage for further developing those mental factors when we develop concentration.

Also, by keeping good ethical conduct, it prevents a lot of hindrances because when you start to meditate you start to notice your various distractions, and you’ll begin to see habits and patterns in your distractions. Some of you who have been meditating for a while may have begun to notice this. “Oh, my mind always goes towards food, or sex, or thinking about how it’s not fair how my boss is treating me, or how I’m angry at this person.” You begin to see the areas where you are stuck, and a lot of the distraction can come from non virtuous actions that we’ve done.

We’ll sit down to meditate and we replay a conversation we had with somebody. Have you done that? We replay two kinds of conversations: the ones in which somebody is telling us how wonderful we are and how much they love us, and the one where we quarreled with somebody. And a third one we’ll replay is the one we just had, even if it was inconsequential, but with the thought of, “Oh, maybe I should have said this or that, or what does that person think of me? We were talking about x, y, or z, and I said that, but I didn’t say it clearly; I distorted it. I wonder if they noticed. Or maybe I should have embellished the story a little more, so they would have been attracted to me. What’s wrong with embellishing the story anyway?”

We’ll find that we’re replaying conversations, and a lot of those do have to do with our ethical conduct: “Did I speak truthfully? Oh, I said that. That was not such a nice thing to say to somebody; I feel some regret.” Or maybe we sit down and we’re still angry: “They said that to me; I should have really given it to them.” Then we replay that conversation in a new way: “I’m going to stick up for myself and let them know what I really think here.”

All these distractions come into the mind, and they have to do with our ethical conduct. The deeper you get into meditation, the more stuff comes up in your mind, the more stuff you replay from the past. It’s kind of like sometimes vomiting your garbage, but it’s part of the purification. Don’t get upset or alarmed with it; it’s just a natural process. We begin to see the errors that we’ve made in our lives and realize that we have some regret and we need to do some purification. So, that also comes up.

Another practice that’s done in a Buddhist culture, with people who really live the Dharma day-to-day, is purification practice. It’s done on a daily basis here at the Abbey. During the next session when we do the bowing to the Buddha, there’s purification happening there, and then in the morning with the practice of the 35 Buddhas, that’s a strong purification practice. All that helps us release different negativities so that when we meditate those things don’t arise as distractions or as doubts.

It’s a whole process of purification, creating merit, listening to teachings, thinking and discussing teachings and meditating. And then in the break time, we act in constructive and beneficial ways towards other people. This is really practicing the teachings in the break time—trying to live with a kind heart towards the people around us. All of this is related to developing concentration and meditation in general in a Buddhist practice. It’s not just sitting down quietly and focusing your mind on something. It’s really a whole embodied experience that exercises our body and mind in many different ways.

The physical meditation posture

Then, let’s just go over your physical posture when you’re meditating. Sit cross legged. If you can sit in the vajra position, that’s very good. Most people can’t, but if you can, that’s very good. In this position you put your left leg on your right thigh and your right foot on your left thigh. That’s called the vajra position. If you can’t do that then it’s good to sit cross legged, like we did in Kindergarten. And then also there’s the position like Tara. Tara is the female Buddha. In the Thangkas and statues, she has her right leg positioned like she’s stepping out, but in meditation what you do is put your left foot flat on the floor and then you have your right foot also flat on the floor in front of it. If none of the floor seating positions work then you can try a bench. Other than that, sit in a chair. If you’re sitting in a chair then have your feet flat on the floor and make sure when you’re meditating that you’re sitting up straight, not leaning back on the chair.

You want your body to be as comfortable as possible, but it is one hundred percent impossible to make your body completely comfortable. So, I’m just telling you now that you will never find the ideal position or the ideal cushion. And your body will never been one hundred percent comfortable. Why? Because we have a body that is under the influence of afflictions and karma. We have a body, the nature of which is to get uncomfortable and to get old and to get sick and to finally die. That’s the nature of this body. If you don’t like having this kind of body then the person you complain to is yourself: Why do I have this body? Because I didn’t practice the Dharma in a previous life, so I didn’t attain liberation. I don’t have a body made of light because I didn’t create the causes for it.

You can’t really complain to the Buddha. You can’t really complain to the manufacturers of the cushions. [laughter] They are kind people doing their best. We will try and find some way to complain: “The carpet is too rough. Why don’t they have softer carpet?” You should have been in here before we had carpet. We can tell you what that was like. [laughter] So, try and find a cushion. Don’t sit flat on the floor, have your tush raised. Some people like hard cushions or soft or flat or puffy—you can experiment with them all. That’s fine, but pick one and just recognize that you’ll never be totally comfortable. You can put another cushion under yourself if you want or a cushion under one leg. You can get a meditation band. You can do the whole nine yards; that’s fine. Do whatever you want. [laughter] but just remember at the end that you have a body that is in the nature of being uncomfortable. We have to make friends with our body in one way or another.

We might think, “Okay, the body is not so comfortable, so I’ll do some yoga or tai chi or take a walk.” I really highly recommend getting some exercise and especially looking long distances. That’s quite important, but don’t expect yourself to sit down and be comfortable and there you go into some deep meditative state for the rest of the period—unless you’re somebody who has a lot of meditative training from previous lives and were lying on the beach with me and eating ice cream and drinking tea with me in previous lives. [laughter] Then we’re all going to have the same difficulties.

So, your physical posture is to sit up straight, legs crossed, back of your right hand on the palm of your left hand, thumbs touching. And this is in your lap but next to your body. It’s not out way in front of you. When you’re sitting like that, very naturally there’s a space between your body and your arms. So, don’t put your arms in unnaturally or stick them out like chicken wings, just sit comfortably with some space there, and the air circulates there. Then keep your head level. You might tuck your chin in just a tiny bit, every so slightly, not very much. Don’t tuck it in too much because it keeps going down when you do. Keep your mouth closed unless you have very bad allergies in which case breathe any way you want to or can. They say to keep your tongue on the palate of your mouth. In my mouth I’m not sure where else my tongue would go. [laughter] But I’ve been told I have a big mouth; maybe your mouth is bigger and there are other places your tongue can go. [laughter] But that’s where mine winds up.

Relaxing the body

So, you’re sitting up straight, and it’s good to do the body relaxation. Learn to lead yourself though that and deliberately check out where your tension is and learn to relax the different parts of your body. You learn a lot about yourself that way, by seeing where you store your tension. And then do the body relaxation, bringing your attention to where we are right now and then starting with your feet and legs and checking the sensations, then going to your belly and abdomen. And then really check if you’re somebody who stores a lot of your tension and nervousness and everything else in your belly. If you are, just let your belly relax because when we breathe, our belly should be going out. Often in modern society we’re so tense that when we breathe, we breathe from the top part of our lungs, and our belly stays the same and just the top part of our chest moves. You really want to make sure your diaphragm is moving when you’re breathing.

Then check your shoulders, your back, your chest and everything. I know for me the tension goes in the shoulders. Some of us have computer posture: hunched over like at a keyboard. I won’t say who, but I know people in the community quite well. [laughter] Meditation posture is straight, and you have to take your head back in, you’re not looking at a screen and you’re sitting up straight. And check your head, too, because sometimes the tension goes into our neck or our clenched jaws. Feel your face, too. Sometimes the facial muscles are scrunched. It’s a little bit of tension just in your face. Or there are some people who when they’re meditating, their brows scrunch up just a little bit. You don’t want your brows like that; you want your brows relaxed.

One time I was asked to go to a Montessori school and teach the kids some meditation. I remember one little girl who was sitting there with her legs crossed and had her eyes and face just completely scrunched up because she really wanted to concentrate. And that’s how you concentrate. [laughter] No, that’s not how we concentrate. We should be relaxed. But relaxed doesn’t mean sloppy, and it doesn’t mean sleepy. It just means free of tension.

Breathing meditation

And then for the breathing meditation. You can choose one of two points. If you’re focusing on the belly then you really have to make sure that your belly is extending as you inhale and that it’s collapsing or falling as you exhale. This does not mean deep breathing. Please do not deep breathe, especially in a group meditation. Because every once in a while, the room is quiet and we get someone who is just breathing so deeply that it becomes distracting. Please don’t do that. [laughter] Just let your breathing be the way it naturally is. You will learn something from watching your breathing patterns because your breathing pattern will be different at different times in your life. It’s really related to what’s going on in your mind.

When your mind is tranquil, your breath tends to be slower, and it tends to go down deep into your belly. When we’re nervous or stressed, our breath is shorter and stays at the top of our lungs. It’s very interesting. Try this: put one hand on your chest and one hand on your belly and then breathe so that you can see your belly is extending when you inhale. And then breathe where your belly is not moving but you’re breathing at the top of your chest. Do you feel the difference?

How do you normally breathe? It’s interesting to sit down and watch how we normally breathe. Are we normally slightly tense, rushed and breathing at the top of our chest? Or are we normally more relaxed? The breath will be different at different times, and you can learn a lot about what is going on in your mind, about your mental state, by watching how your breath happens to be at a certain time. You can observe how your breath correlates to your mental state, and you can learn a lot.

You can put your attention at your belly or at your upper lip and the nostrils, and here you’re watching the physical sensations of the air as it passes. This is much more subtle than watching the sensation of your belly rising and falling. When you sit down, don’t try and manipulate your breath. Just let it be what it is. As you meditate, it may change. So, you just let it change, and like I said, it’s because your mind also is changing.

Dealing with distractions

Distractions will come up; that’s very natural. The key is how to handle the distractions. If you’re anything like me, you have a very active mind and an opinion about everything. There’s a sound in the room, and you think, “Who is making that sound? Oh, that person. They are always making noise. They always come in late. I sit next to them during lunch, and they’re always chewing so loud. They remind me of this kid I went to third grade with who always chewed really loudly. He had red hair. I’ve met a lot of people with red hair in my life. I wonder if there’s any correlation between red hair and personality. There might be. That would be an interesting psychological study. Where can I get funding to do that?”

Do you see? The mind just takes one small thing, and we are off and running, writing a story about it, full of our opinions. Just notice the sound, that’s all. You don’t need to look and see who made it. Just notice the sound and come back. See your breath as home, and keep coming home to your breath, no matter how many times you get distracted. It’s kind of like having a little kid, and you know how they have leashes now for children? That’s probably not the proper word. There must be a nicer word.

Audience: Child restraint.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): That sounds like it would traumatize you. [laughter] What’s the correct term, those of you with children?

Audience: A tether.

VTC: A child tether. [laughter] That doesn’t sound so nice either; it sounds like a cow you tether. [laughter]

So, it’s like having a child on a leash. Your kid runs off, but you bring them back. They run off again, and you bring them back. They run off, and you bring them back. Okay? Each time your child runs off, you don’t scream at them. That’s not going to work. Similarly, each time you get distracted, you don’t scream at yourself. It’s just: “Okay, there’s a distraction. Here’s the leash; we’re coming home now to the breath.” And you bring your attention back to the breath however many times that needs to happen.

And, like I said, you’ll begin to notice patterns of distraction. That’s okay. It will tell you what you need to work on in other kinds of meditation that you do, that work more as the antidotes to different kinds of distractions. One thing that we lose on is the mind is wandering around touring the universe, mostly with attachment but it could also be with anger—either that or we’re slowly falling asleep. [laughter] You can see I’m quite good at this; it happens especially when you sit in the front row where everybody is looking at you. [laughter]

If you’re getting drowsy in your meditation, it’s usually not because you’re short on sleep. This is usually a karmic obstruction; it’s another way our self-centered mind distracts us from doing what we need to be doing. Some tips on that are to get some exercise during the break time and invigorate your body. And look into long distances, especially going to the top of the hill there and looking at the sky and the forest. It’s very good. Or do some yoga or tai chi or whatever you prefer. That’s also quite good. Splash cold water on your face or head before you come and sit down. Do prostrations; those are also good.

And then this actually brings me back to one part of the meditation posture that I forgot to mention, which is what to do with our eyes. Don’t roll them back in your head. They say it’s good if you can have your eyes just a little bit open but not looking at anything. They’re just a little bit open so that some light comes in, and if they’re looking at anything, it’s down here by your legs, by the cushion, the carpet or whatever is beneath you. By letting some light in, it prevents drowsiness. It’s a good antidote to drowsiness.

I think I’ve given enough instructions for that. The next session you’ll have the chanting and then the seated meditation. We’ll start out with the breath. The breath is the object of meditation, but it doesn’t work well for everybody. So, in the next session I will explain a meditation on the Buddha that you can do using the visualized image of the Buddha as our object of meditation. But for now, have it very clear what your object of meditation is; it’s the breath. Put your mental factor of mindfulness or remembrance on the breath when you sit down. It’s not going to go there automatically. You have to sit there and go, “Now I’m going to put my mindfulness on my object of meditation. My object is the breath, so I’m putting my attention and my mindfulness there.”

That mental factor of mindfulness helps you remember your object of meditation and keep your attention on it. There’s another mental factor that works in tandem with mindfulness called introspective awareness, and this is a mental factor that checks up every once in awhile: “Am I still on the breath [or whatever our object of meditation is], or am I getting drowsy, or am I in la-la land dreaming about something, or am I getting angry, or am I giving a discourse to somebody in my meditation?”

Introspective awareness is used to survey the land of your mind every once in a while: “What’s going on in my mind? Am I on the breath or am I drowsy or am I wandering?” If we’re wandering, come back. If we’re drowsy, we check our posture and sit up straight, make sure our eyes are a little bit open. These two mental factors, mindfulness and introspective awareness, are very important, and we develop them by keeping ethical conduct, but I’ll talk about that later.

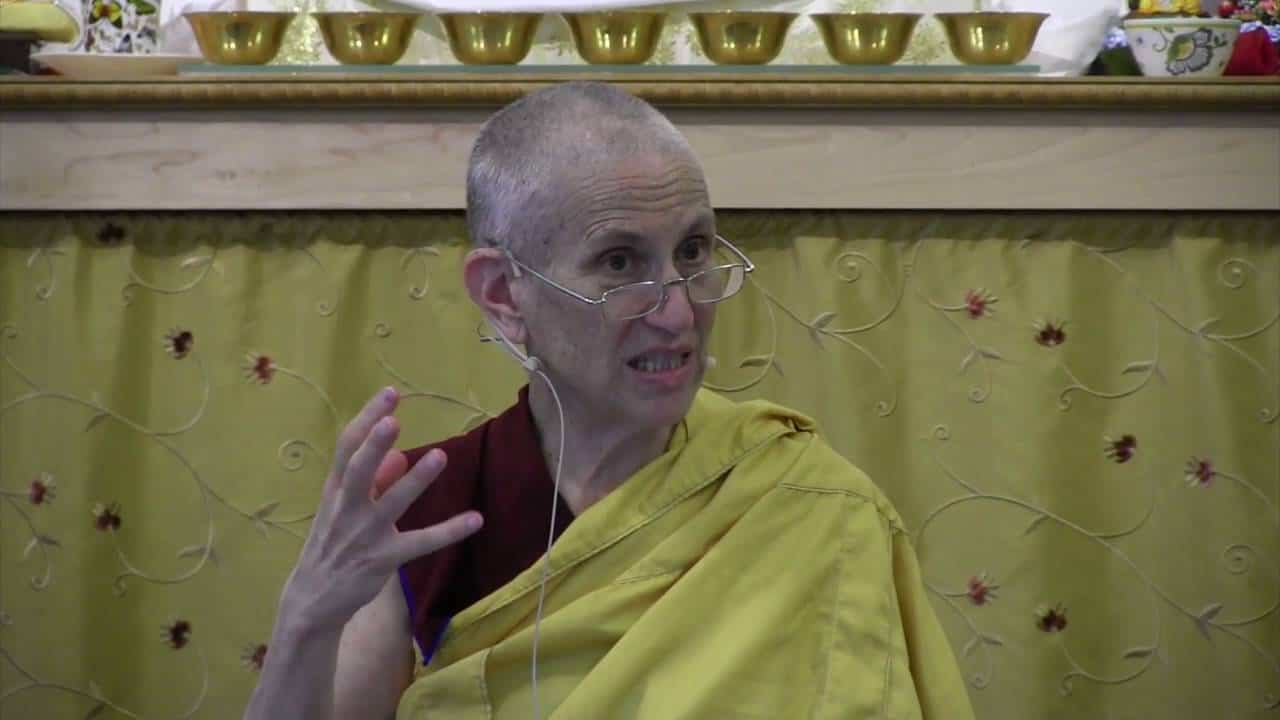

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.