Concentration meditation on the Buddha

Part of a series of teachings given during the Developing Meditative Concentration Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2016.

- Mindfulness and introspective awareness

- How they apply to ethical conduct and our daily life

- 35 Buddhas oral transmission

- Using an image of the Buddha as our meditation object

- Overcoming pitfalls

- Relating to the Buddha

- Meditation on the Buddha

As I was saying in the morning, two of the mental factors that are very important for developing concentration or serenity are two that are very important for ethical conduct as well. Since ethical conduct is easier to do because it involves body and speech, which are grosser activities, those are easier than developing concentration, which involves just our mind. So it’s good to train in ethical conduct first to develop those two mental factors and also to clean up our behavior so we don’t have so many distractions coming in our meditation in the form of regret for our nonvirtuous behavior, confusion over what we did in our past—was it ok, was it not ok? The more we are able to improve our ethical living, the easier meditation becomes. Fewer distractions and fewer internal conflicts.

In ethical conduct, mindfulness is aware of our precepts. It’s aware of our values and principles, and we keep these in mind whenever we are doing something. Whether we are standing, sitting, walking, lying down, we keep our ethical principles in mind. This is a big protection, and it’s a good thing to focus on, to keep the mind focused as much as possible on these things, especially when we’re at work when we’re talking to other people so that we can monitor what we’re saying. When we’re writing emails, for example, because if we aren’t very mindful when we are writing emails, we say all sorts of negative stuff, don’t we? Also, when you are texting because the person is not there in front of you, so it’s easier to say nasty things and press send and not have to deal with seeing the effect that our words have on somebody else. And yet, we create a lot of negativity and get ourselves into plenty of jams that way also.

The other mental factor for introspective awareness is checking up and saying, What am I doing? Am I living according to the things I am being mindful of or am I out to lunch? It has all sorts of implications for our daily lives. For example, just being aware and being careful of how we move through space. How much do we slow down and pay attention to that? Or, when we’re walking somewhere, is our mind already at the destination? And we’re not being careful where we’re putting our feet—are there any bugs under our feet? We’re not aware of how we close and open doors. If we could be making a lot of noise that is disturbing others. We’re not aware of our footsteps, whether we’re clomping down the hall, waking someone up or whether we are walking smoothly and gently. Just even basic things like this. How we move through space—to become more attentive to that.

Similarly, to become more mindful and have more introspective awareness about what we’re saying and how we’re saying it. Instead of just the impulse coming to mind and the words coming out, but to really think and be careful. “What is the tone of my voice?” Because we all know, from listening to other people, that the tone of their voice often tells you more than the words that they’re saying. Doesn’t it? You can say the same words with two different tones of voice, and they have two different meanings. So what is our tone of voice? What is the volume of our voice? If we’re speaking really loud—why is it? If we are not speaking loud enough—why is that? If we’re mumbling our words—what’s going on? Using that to monitor our behavior and see how we are communicating with other people.

Also being aware of our body language when we are communicating, because again, we know that body language expresses a lot, sometimes more than the words. You could be saying many loving caring things to somebody, but if you are standing there saying them like this (arms folded) what message is it giving? I really care so much about you, you are really important in my life, and you are holding your arms like this. Is that matching? It’s not, is it? How are we standing, especially when we talk to somebody who we consider in a position of authority or someone that we consider is in a lower position than us. How do we stand? Do we stand with our legs apart and our chest put out when we talk to people? What’s that saying? Do you go to your boss and stand like that? I don’t think so. Do you stand like that to people you want to dominate? Probably. What is that saying to them? Are you saying, “Be afraid of me,” because you think, you are confusing somebody respecting you with somebody fearing you?

Be aware of our body language, our voice and so on, and a lot of this has to do with gender as well. To be aware of how we impute motivations corresponding to our expectations of how women speak and hold their bodies and how men speak and hold their bodies. It has been pointed out so much if a woman is speaking directly and straightforwardly, then often both men and women think, “Oh, what a … She is bossing everybody around and trying to be dominant.” Whereas if men speak the same way, hold their body the same way, it is perfectly normal. So to be aware of our judgments and opinions about that kind of thing and see if they are fair. When we impute gender roles on people, is that really something fair based on their voice? We all hear that Hillary’s shrill. Trump is not shrill? No, it is fine for a man to speak like that. When Hillary is straightforward, not so good. We judge. Be aware of our judgments against people.

All of this has to do with ethical conduct and becoming more aware. And that thing of becoming more aware, more mindful, having more introspective awareness is very important in our meditation as well so that we can sit and put our focus, our attention, on the object of meditation. If we don’t have very good mindfulness, we sit down, sitting in perfect position and immediately let our mind wander. Have you ever done that? Especially if you are used to having a daily practice. Sit down, start your mantra, and let the mind wander. [laughter]. “What should I wander to today while I am reciting mantra?” We do this, don’t we? Then not much introspective awareness, bringing our mind back once or maybe twice, but, “Gee, that distraction is so interesting.” Using our morning meditation to make our list for the day.

So trying to become aware of what’s going on in our mind and keeping our attention where we want it to be, and when it goes off, then returning it to where it wants to be. Sometimes we’re getting drowsy, and we don’t even notice it. Sometimes even we’ll call up a little bit of introspective awareness and say, “Oh I’m clear” but if you observe your mind just a moment longer you’ll realize you’re saying, “Oh, I’m on the object” just out of habit, but actually you are beginning to fade. There is some laxity coming into the mind. We have to work on our ethical conduct so that we can bring it into our practice of concentration.

Along that line, someone has asked me to give the transmission for the practice of the 35 Buddhas, which I thought I would do very quickly. It’s a purification practice, and when you are practicing the Dharma, it’s good to do regular purification because it helps you clear up things from the past and purify them. Do a little life review—see what we feel good about and see what we don’t feel good about. Generate regret for things we don’t feel good about, think of how else we could feel and think and behave if similar situations come in the future. Making a determination not to do the action again. All of these are what we call the four opponent powers of purification are very helpful for calming the mind and clarifying it and stopping these kinds of impediments to concentration.

Especially, for example, sleepiness and drowsiness. Like I was saying, I think very often that’s something karmic that’s coming up. Either karmic or it’s just our self-centered attitude’s way of saying, “I’m going to do what I want. I don’t feel like trying to concentrate, so I’ll just fall asleep instead.” Often it does come as a result of disrespecting holy objects. For example, putting our Dharma materials on the floor, stepping over them, throwing them in the trash, things like this. It can create an obscuration on the mind. Or being disrespectful to the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, also creates obscuration so that either we have trouble meeting the Dharma or if we meet it, we have trouble staying awake and focusing on teachings, staying awake during our meditation. Purification practice is very good for counteracting that.

With the oral transmission, all you have to do is listen. But you have to listen. It is in English. If it were in Tibetan, and I wasn’t reading it in English, you don’t have to focus so much on the Tibetan. But it is in English, so I think it is good for you to focus.

So, let me find it. Page 59. I will just read it because giving you oral transmission—the Tibetan word is lung—through doing it and hearing it. Having the teachings and the explanation is something else.

Om Namo Manjushriye Namo Sushriye Namo Uttama Shriye Soha

https://thubtenchodron.org/2011/06/visualization-thirty-five-buddhas/

I, (say your name) throughout all times, take refuge in the Gurus; I take refuge in the Buddhas; I take refuge in the Dharma; I take refuge in the Sangha.

To the Founder, the Transcendent Destroyer, the One Thus Gone. the Foe Destroyer, the Fully Awakened One, the Glorious Conqueror from the Sakyas I bow down.

To the One Thus Gone, the Great Destroyer, Destroying with Vajra Essence, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Jewel Radiating Light, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the King with Power over the Nagas, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Leader of the Warriors, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious Blissful One, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Jewel Fire, I bow down.

To the One Thus Gone, the Jewel Moonlight I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, Whose Pure Vision Brings Accomplishments I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Jewel Moon, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Stainless One, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious Giver, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Pure One, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Bestower of Purity, I bow down.

To the One Thus Gone, the Celestial Waters, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Deity of the Celestial Waters, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious Good, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious Sandalwood, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the One of Unlimited Splendour, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious Light, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious One without Sorrow, I bow down.

To the One Thus Gone, the Son of the Desireless One, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious Flower, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, Who Understands Reality Enjoying the Radiant Light of Purity, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, Who Understands Reality Enjoying the Radiant Light of the Lotus, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious Gem, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious One who is Mindful, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious One whose Name is Extremely Renowned, I bow down.

To the One Thus Gone, the King Holding the Banner of Victory over the Senses, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious One who Subdues Everything Completely, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Victorious One in All Battles, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious One Gone to Perfect Self-control, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Glorious One who Enhances and Illuminates Completely, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Jewel Lotus who Subdues All, I bow down.To the One Thus Gone, the Foe Destroyer, the Fully Awakened One, the King with Power over Mount Meru, always remaining in the Jewel and the Lotus, I bow down.

In this life, and throughout beginningless lives in all the realms of samsara, I have created, caused others to create, and rejoiced at the creation of destructive actions such as misusing offerings to holy objects, misusing offerings to the Sangha, stealing the possessions of the Sangha of the ten directions; I have caused others to create these destructive actions and rejoiced at their creation.

I have created the five heinous actions, caused others to create them and rejoiced at their creation. I have committed the ten non-virtuous actions, involved others in them, and rejoiced in their involvement.

Being obscured by all this karma, I have created the cause for myself and other sentient beings to be reborn in the hells, as animals, as hungry ghosts, in irreligious places, amongst barbarians, as long-lived gods, with imperfect senses, holding wrong views, and being displeased with the presence of a Buddha.

Now before these Buddhas, transcendent destroyers who have become transcendental wisdom, who have become the compassionate eye, who have become witnesses, who have become valid and see with their omniscient minds, I am confessing and accepting all these actions as destructive. I will not conceal or hide them, and from now on, I will refrain from committing these destructive actions.

Buddhas and transcendent destroyers, please give me your attention: in this life and throughout beginningless lives in all the realms of samsara, whatever root of virtue I have created through even the smallest acts of charity such as giving one mouthful of food to a being born as an animal, whatever root of virtue I have created by keeping pure ethical conduct, whatever root of virtue I have created by abiding in pure conduct, whatever root of virtue I have created by fully ripening sentient beings’ minds, whatever root of virtue I have created by generating bodhicitta, whatever root of virtue I have created of the highest transcendental wisdom.

Bringing together all these merits of both myself and others, I now dedicate them to the highest of which there is no higher, to that even above the highest, to the highest of the high, to the higher of the high. Thus, I dedicate them completely to the highest, fully accomplished awakening.

Just as the Buddhas and transcendent destroyers of the past have dedicated, just as the Buddhas and transcendent destroyers of the future will dedicate, and just as the Buddhas and transcendent destroyers of the present are dedicating, in the same way I make this dedication.

I confess all my destructive actions separately and rejoice in all merits. I implore all the Buddhas to grant my request that I may realize the ultimate, sublime, highest transcendental wisdom.

To the sublime kings of the human beings living now to those of the past, and to those who have yet to appear, to all those whose knowledge is as vast as an infinite ocean, with my hands folded in respect, I go for refuge.

Then there is the general confession afterwards. U hu lag that is what they say in Tibetan, instead of ‘woe is me’, U hu lag.

Woe is me!

O spiritual mentors, great vajra holders, and all the Buddhas and bodhisattvas who abide in the ten directions, as well as all the venerable Sangha, please pay attention to me.

I, who am named _, circling in cyclic existence since beginningless time until the present, overpowered by afflictions such as attachment, hostility, and ignorance, have created the ten destructive actions by means of body, speech, and mind. I have engaged in the five heinous actions and the five parallel heinous actions. I have transgressed the precepts of individual liberation, contradicted the trainings of a bodhisattva, broken the tantric commitments. I have been disrespectful to my kind parents, spiritual mentors, spiritual friends, and those following the pure paths. I have committed actions harmful to the Three Jewels, avoided the holy Dharma, criticized the Arya Sangha, and harmed living beings. These and many other destructive actions I have done, have caused others to do, and have rejoiced in others’ doing. In short, I have created many obstacles to my own higher rebirth and liberation and have planted countless seeds for further wanderings in cyclic existence and miserable states of being.

Now in the presence of the spiritual mentors, the great vajra holders, all the Buddhas and bodhisattvas who abide in the ten directions, and the venerable Sangha, I confess all of these destructive actions, I will not conceal them, and I accept them as destructive. I promise to refrain from doing these actions again in the future. By confessing and acknowledging them, I will attain and abide in happiness, while by not confessing and acknowledging them, true happiness will not come.

The point of having the oral transmission is you’re taking something that the Buddha said, that his disciples heard that he said, and their disciples heard. It is like passing on that transmission of the words from the Buddha to us. That’s why we have the oral transmissions.

Then also, as I mentioned this morning, breathing meditation is not necessarily the thing that works best for people when developing serenity or concentration. I use the term serenity, other people use calm abiding, but it’s the same thing. There are different objects of meditation. The Buddha talked about a whole bunch of them, both in the Pali scriptures and the Sanskrit scriptures. Some of them are rather neutral objects like the breath or in the Pali tradition you might focus on a color, a certain color or on a clay image of a certain color or of a certain material. You may focus on the four immeasurables of love, compassion, joy and equanimity. There are so many different ones. We don’t have time to go through all of them now.

One that is quite popular in the Sanskrit tradition is focusing on the image, the visualized image of the Buddha, and this has certain advantages to it over using the breath. Because when we visualize the Buddha, we’re creating a connection with the Buddha. Just the physical image of the Buddha, his body language, the way his eyes are looking, his expression, all of this is a manifestation of internal qualities, and when we visualize it, then we’re making a connection with those virtuous qualities, which of course are qualities that we ourselves want to generate inside of ourselves. Also when we visualize the Buddha and make this kind of connection, it helps us remember our refuge throughout the day and remember the Buddha throughout the day and that can be very helpful. When you’re somewhere and you’re starting to get flustered or stressed out, because you have the familiarity with the Buddha from using that image, when you’re training in serenity, it’s easier for the image of the Buddha to come into your mind during the day. When you’re getting flustered, stressed out and you are starting to get angry, you think of the Buddha, and immediately that has an effect on your mind. I mean look at the expression on the Buddha’s face. Is that an angry tense belligerent expression? No. When you visualize that, that’s going to have an internal effect on you.

What we put our attention on, I guess if you want to understand it psychologically, it’s like when they did those tests in the movie theatre if you flash something on the screen like Pepsi, then everybody wants to go and get Pepsi and things like that. In a similar kind of way, if we have this habituation with a figure like the Buddha, even if it just flashes in our mind, it influences us. I think that’s also why it’s very advantageous to have a shrine or an altar in your house because you have it in a place where you walk by and you’re beginning to get really ticked off and then you walk by the image of the Buddha and it’s like, “Okay, I have got to chill out. Buddha’s completely calm—why am I so irascible? I can calm down right now—this isn’t such a big thing.” It helps us. Images speak to us. That’s why artists express themselves through images because it’s a form of language and communication. When we visualize the Buddha in that way, it communicates the qualities to us.

And when it comes time to die, if we can remember the Buddha, then it’s really good because, if we visualize the Buddha, remember the Buddha, then we have strong refuge in our mind. And if we have refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha at the time we’re dying, then since that is a virtuous mind, it’s going to make the seed of a virtuous karma ripen and that will propel us into a good rebirth. Whereas if we die and we’re angry and we’re just imagining the person that you know we dislike, then that’s going to make the seed of a negative action ripen and throw us into an unfortunate rebirth. So developing this familiarity with the Buddha is really beneficial throughout our life and especially at the time of death.

When we visualize the Buddha, we aren’t trying to see the Buddha with our eyes, we’re imagining the Buddha with our mind’s eye, so to speak. Some people say to me, “I can’t visualize,” but if I say, “Think of pizza.” Do you have an image of pizza in your mind when I say, “Think of pizza?” Yes you have an image very clearly in your mind, don’t you. That’s visualization. If I say, “Think of your mother,” do you have an image in your mind? Even when your eyes are wide open, even when your mother is no longer here, there’s an image, isn’t there of what your mother looks like. If I say think of your bedroom, you have an image of the room you live in. All of that—this is the same kind of thing that we’re talking about.

Now why is it easier to visualize your partner than to visualize the Buddha. It’s a matter of familiarity. It’s just a matter of familiarity. What we’re used to seeing and visualizing, it’s easier for that image to come into mind. As we practice imagining the Buddha, then it becomes easier and easier for the image of the Buddha to come into our mind. It’s just a matter of habituation.

So when we visualize the Buddha, we’re visualizing the Buddha maybe about four feet in front of us. This is all just approximate because different people are going to have different ways, and they say maybe about this big. But again your Buddha maybe a little bit bigger, your Buddha may be smaller.

We want to visualize the Buddha made of light. So you’re not imagining a statue made of brass or something or of a two-dimensional painting. You want to think of the Buddha with it, with a body made of golden light. Now we can visualize golden light, can’t we? Yes? I mean what else is golden light? Can you visualize a waterfall with different color lights? You know how they have light behind waterfalls in different places or lights just like in a theatre, different color lights. So we can visualize light. We know what light looks like. You can visualize the Buddha with a body made of golden light like that, and it can be helpful beforehand if you look at a statue or you look at a painting, and you really take it in.

At the beginning you can practice looking at the statue or a painting and then closing your eyes and imagining it and then looking again and closing your eyes and imagining. Don’t get stressed out. This is the thing. Don’t get stressed out if your image is not as crystal clear as you would like it. Because remember you’re not trying to see it with your eyes. You’re seeing it with your mind’s eye. And there may be one part of the Buddha’s body that really zaps you, and it’s easier to focus on that. Then you can focus on that, but the whole body is still there. It’s kind of like when you’re talking to somebody, you may look at their face, you may focus on their eyes or focus on some other part but you’re aware that the whole person is there. When you’re imagining the Buddha, like if it’s the Buddha’s eyes, which I think are so beautiful, and you’re focusing on them. It’s not like they’re disembodied eyes out there. I mean there’s a whole person there even though the entire image may not be super crystal clear to you.

I think it’s also important when you’re imagining Buddha, the expression on the Buddha’s face is one of complete acceptance and complete compassion. We’re visualizing the Buddha, and the Buddha is looking at us with acceptance and with compassion. For some of us, this might be a little bit uncomfortable in the beginning because immediately when we think of somebody like the Buddha, our mind goes, “Authority figure.” And then we go, “Authority figure, they’re going to judge me.” Some of us have this kind of mental habit, “Oh I’m visualizing the Buddha. Uh oh, the Buddha’s going to judge me. The Buddha has a scowl on his face or even if he’s looking peaceful, I dare not visualize him because how can I imagine the Buddha looking at me with acceptance and compassion because he’s judging me, and why is he judging me because I’m such a defective person. Nobody looks at me with kindness and compassion. Everybody looks at me with animosity and jealousy and competitiveness.” It’s very interesting, you may discover that you actually have trouble imagining someone looking at you with acceptance and kindness and compassion. And you may discover from that that in your life, you have difficulty letting in other people’s affection and care. That as soon as someone shows affection and care, you’re suspicious and you block it out. Very interesting, yes? It’s really important here—the Buddha’s looking at you with 100% acceptance. There’s no judgment. And it’s possible for somebody to look at you that way, so don’t get freaked out by it. Let the Buddha’s compassion come into you.

When we visualize the Buddha, we start by looking at the different attributes. What does his face look like and the eyes, nose and mouth and the long ear lobes which are from wearing jewelry as a prince which stretched out his earlobes. The way he’s sitting completely, his position is completely balanced completely grounded, his right hand is what is called the earth touching position, and that comes because when he attained awakening, I think it was Mara or somebody said, “How do we know you’re completely enlightened?” And he said the earth goddess will testify and confirm it and he touched the ground and the earth goddess appeared, so the story goes.

His left hand is in his lap in a meditative position, and he is holding an alms bowl. This is not a begging bowl. Monastics do not beg. They go on alms. When begging, you ask for something. Alms, you stand there and somebody’s free to give or not to give. The monastics at the time of the Buddha went into town with their arms bowl. People, if they wanted to, put food in the arms bowl. The Buddha’s alms bowl we imagine it is filled with nectar—very purifying and healing nectar. Then his arm is in the earth-touching position.

He is wearing the robes of a fully ordained monastic. The three robes are lower robe is called the shamthap, this is a chogeu and the namjar we don’t have on him. The namjar is another golden colour robe that has even more patches than the shamthap and the chogeu. We don’t have one on the Buddha here. We could certainly make one. It takes a while to make them because there are so many patches. He’s wearing the monastic robes, and visualizing the Buddha as a monastic also gives you a certain vibe so to speak, because the Buddha is keeping good ethical conduct. He has no intention to manipulate you or pull one over on you or, and he’s not coming on to you, and he doesn’t want anything from you. He’s just expressing affection and compassion. Again, imagine somebody relating to us in that way and us relating to them in that way.

At the beginning, we go through, we look at all the details of the Buddha’s body and then we focus on the general image that we get, whatever image it is. Sometimes it’s real clear, sometimes it is just some kind of general golden-colored blob in the shape of a person, that’s good enough. We have to be satisfied with that. As we develop more familiarity, it gets brighter in the same way as the more you eat pizza and the more familiar with that you are, the more detailed your visualization of pizza becomes. You know exactly what toppings are on that pizza, don’t you? You know how big and the way the mushrooms are sliced. You get more details as you become more familiar. Then you focus on the general image. If the general image starts to fade, then you go back again over the details and again focus on the image and hold it as long as you can. If it fades again, again you go over the details and hold the image. Should we try that a little bit?

It’s good at the very beginning just to do the breathing meditation, maybe one or two minutes to settle the mind and then we’ll do some, using the image of the Buddha. You should come back to your breath.

A short distance in front of you, maybe about four feet, imagine the Buddha. He’s seated on an open lotus flower with a moon disk and a sun disk on top of it so they’re like cushions that he is seated upon. The Buddha’s body is made of golden light. His face is very peaceful and calm. His eyes long and narrow, looking at you with acceptance and compassion. His hair is short and blue. He has a crown protuberance on top indicating all the merit he accumulated to become fully awakened. His ear lobes are long. The whole expression on his face is just completely peaceful and at ease. He’s seated in the vajra position. His right hand is on his right knee and touching the earth. His left hand is in his lap and meditative position, holding an alms bowl filled with nectar. His pure morality is symbolized by wearing the monastic robes.

Whatever image you get of the Buddha, focus on that. Use mindfulness to remember that image and to keep your focus on it, and then employ introspective awareness from time to time to see how, if you’re still on that image or if it’s faded you’ve become distracted or what. If you lose the image or it fades too much, again go over the details, and then focus on the whole image, although if there’s one part of the body that really grabs your attention like the eyes, then you can put more focus on them, so we’ll have some silence now to do that.

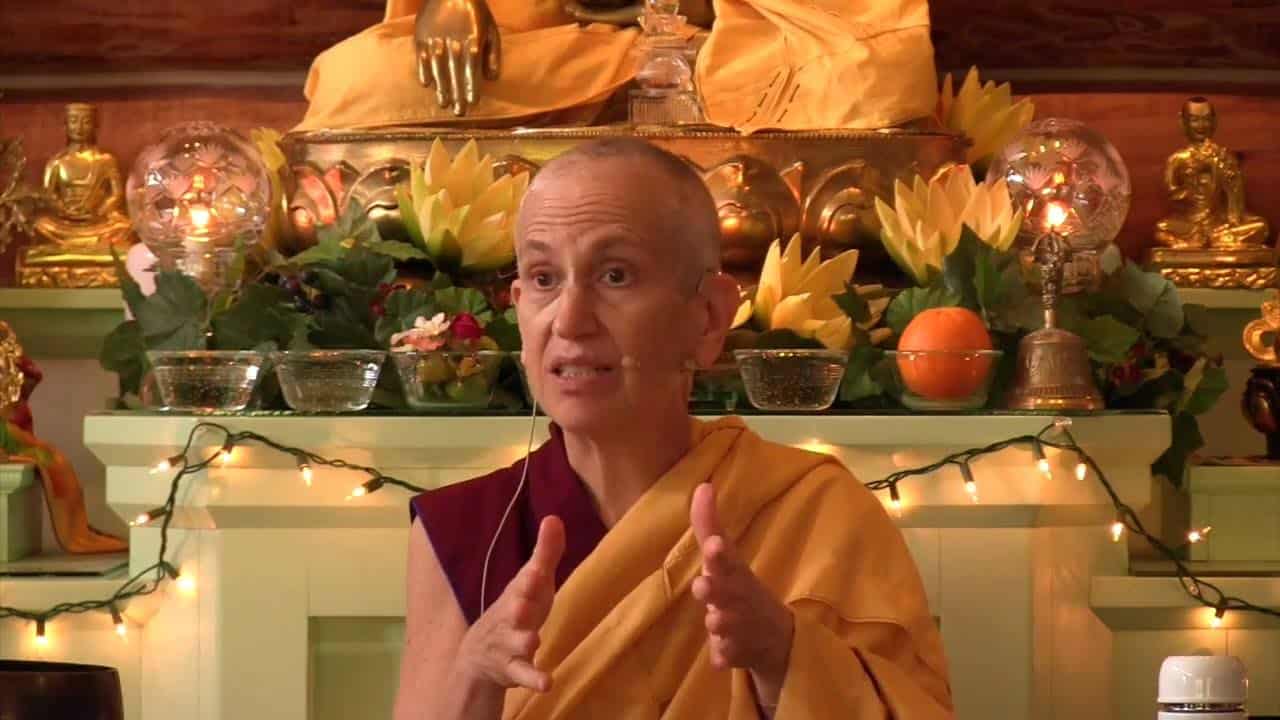

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.