Heart advice for practitioners

A response to a request for advice from Tan Nisabho, a young monastic who ordained in the Thai Forest Tradition after attending the Exploring Monastic Life program in 2012. Tan Nisabho visited Sravasti Abbey again for a few days in May 2015.

- Listening to and learning from others, but thinking for ourselves

- Being transparent, and not defensive when hearing feedback

- Rejoicing in others’ good qualities

- Importance of study and having a long-term view and good motivation

- Being aware of the kindness of others

Heart advice for practitioners (download)

One thing that we had started on the other day was learning to think for yourself, which I think is quite important when you’re in the Dharma.

Learning from others, thinking for ourselves

You really learn from and listen to your teachers, but you think for yourself. Because, especially if it’s a Dharma point, you have to really think “is this true?” or “Is this not true?” Like in the teachings last night, if I’m talking about emptiness don’t just say “oh well, somebody said everything’s empty of inherent existence, so it must be,” but really think about that and understand it, and then in that way it becomes your own and you get it on a really deep internal level.

And then in terms also of other things that go on, not only specific Dharma points, learning from others but thinking for yourself. Also the way the community does things, or the way social issues are regarded, things like that. Then learn and listen from your teachers and others but think for yourself.

I remember one of my teachers, who is wonderful—I mean I just had so much amazing respect for him and learned so much from him—but he thought George Bush was a great President. So I don’t just listen and “my teacher said so, so I believe it.” It’s like, that one…. No, I wasn’t going to…. [laughter] I wasn’t going to buy that one.

And also, we go to our teachers to learn the Dharma, not to learn politics, not to learn social economics, or any of these kinds of topics. So to really take Dharma principles and apply them to things, but do that in our own creative way. Because I think … becoming a monastic does not mean that we’re all coming out of the same cookie cutter. That doesn’t work because we all come into this world with different talents, different dispositions, different interests, and so I think we have to recognize that and work with what we have and use what we have for the benefit of all beings instead of trying to make all fit into the same square hole—especially if you’re round, or star-shaped, or triangular-shaped, or whatever. Use the beauty of your own shape to benefit sentient beings instead of like squeezing yourself trying to be something you’re not.

I learned that trying to be a Tibetan nun, and there was no way I could fit into how they were supposed to act.

Transparency

And also be transparent, and don’t be defensive, because everybody knows our faults anyway, so when somebody gives you some feedback listen. If what they say is right, say thank you very much, I’m working on it. There’s no need to try and paint a pretty picture of how, “Well, I really didn’t mean this, and this got … blah blah blah….” Instead of just saying, “You’re right, I didn’t tell the complete truth.” Just say what is and don’t feel ashamed about it, rather than trying to justify and get defensive, when everybody knows what happened anyway.

I mean if people have gross misunderstanding, of course, correct that and give them the proper information. But transparency, I think, works very well for us psychologically. Rather than covering things up, just … if we broke a precept, there it is. And then we stop all this self-recrimination and guilt and shame and junk like that that really gets in the way of practice.

So the importance of confession and just saying it, here it is, instead of, “Well, you know, I did that but it’s really that person’s fault….” You know? Own our own responsibility in things. But don’t own what isn’t our responsibility.

Rejoicing

Then also very important is rejoicing at other people’s good qualities, and not comparing yourself to others. Because comparing ourselves to others just gets us…. It digs us into a ditch, especially when you’re trying to do Dharma practice. “Oh that person sits better than I do…. That person looks better than I do…. That person has more faith than I do…. That person’s smarter…. That person’s heard more teachings…. That person’s done more retreat….” You know, comparing ourselves to others and competing with others, it’s useless in Dharma practice. Just do your practice. And when you see good qualities in others be happy about it, because it’s nice that other people have good qualities and are better than we are. And when you’re better than they are, so what, don’t make a big deal about it. Again, just get out of this whole thing of comparing. Because we’re not having a race to see who gets enlightened faster. That’s not our motive. Our motivation is to benefit sentient beings. So everybody does that in their own way. We don’t need to compete.

A long-term view

Have a long-term view. Be content to create the causes in your practice by following the teachings, and stop waiting for grandiose flashes of insight to occur, and instances of samadhi that then you can go tell everybody you’ve had. But just be content to do your practice.

Study

Study. Because study is important. If we don’t study we don’t know how to meditate. If we don’t study we don’t know what the Dharma is and we wind up making up our own path. And that’s dangerous. So it’s really important to study from not only the sutras but from the great commentators and the learned masters.

Motivation

Have a good motivation for our practice. Really make cultivating motivation a really chief focus. Because if we have a good motivation of wanting to attain liberation, wanting to work for sentient beings, and thus wanting to attain full awakening, then that long-term motivation will sustain us through the ups and downs of practice. If our motivation in the back of our mind is to have some kind of peak experience, or to become a Dharma teacher, or something like that, that motivation will not sustain our practice, and it also contaminates our practice with worldly gain and wanting to be somebody. “I’m practicing so I can be a Dharma teacher. Then I have a career.” Yes? Dharma’s not a career. Dharma is our life.

The kindness of others

Remember the kindness of others all the time and really make that a chief meditation. I find, personally, that that helps the mind so much, is reflecting on the kindness of others, because it just makes relationships with other people easier, it reduces anger, it reduces competition, it reduces jealousy. It just, for me anyway, thinking of the kindness of others just brings much more contentment to the mind. So not only the kindness of parents and teachers and friends, but the kindness of strangers, and the kindness of people who harm us as well.

And then when you ask others for guidance really listen to the guidance they give you, but like I said, think for yourself. And when others ask you for help in the Dharma really listen to them before saying something. Try to hear when people ask you questions what their real question is, what their real concern is, and address that.

Dharma and institutions

I mentioned this before, differentiate between what is Dharma and what is “religious institutions.” Because they’re completely different. The Dharma is our refuge, with the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, direct access. A religious institution is something formed by human beings and, of course, not all Buddhists are buddhas, so religious institutions are going to have difficulties, and so on. So I see our job as going deep in our refuge and deep in our practice, and to have as much of a religious institution as is necessary to encourage practice, but not one bit more. In other words, our purpose is not to create and reinforce and be a “team member” of a religious institution, our aim is inner transformation. So not to confuse the two things.

Because institutions have problems. And if your refuge is in the institution, when the institution has a problem then your refuge gets shaky. But if your refuge is in the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, then you know that even when institutions have problems you can bring compassion and wisdom to those problems without letting those problems make you discouraged or cause you to lose faith in anything.

So that’s what I thought of so far. Anybody have questions or comments?

A balancing act

[In response to audience] Right, it’s a balancing act between learning from others and thinking for ourselves. And especially at the beginning you really want to learn and listen. But again, even as you’re learning and listening you have to think about the teachings yourself. If somebody says you have a precious human life, do you just go, “Yeah, I do, because you said so?” That’s not going to bring stability in your practice. Whereas if you really think for yourself about what the qualities of a precious human life are then it really comes home in your heart what you have.

So in saying this I’m not saying don’t accept any guidance, definitely accept guidance, but try and understand the reason for the guidance, and then see if the guidance is in the Dharma or if the guidance has to do with cultural choices, or politics, or something like that. Because we and our teachers can have different political views, like I said. We can have different views on social issues. We have to think for ourselves about all those things.

[In response to audience] Yes, it’s a balance thing. You don’t want to be so opinionated that you can’t learn from anybody, because that’s useless. Then you become very unhappy as a monastic because you think that you’re very close to enlightenment and nobody’s listening to your wonderful opinions that you’ve had all your life about what everybody should do. So those things have to be given up (in order) to be a happy monastic. Actually, just to be a happy person, period. If we have too many opinions, and we grasp onto our own ideas and opinions too strongly, we’re going to be quite miserable.

Even my sister, who’s not a Buddhist, she said that in a recent email. She has two teenaged kids and her kids are really good, they’re not the rebellious type, but she said, “I’m really learning not to have too many opinions because they just get you into trouble.”

[In response to audience] So you’re saying that when your mind’s very confused then it’s better to err towards the side of listening to somebody who has more wisdom and compassion than you do, who can give you solid advice and guidance. Yes, for sure. For sure. But then you definitely have to work it out with your own mind so that you understand that guidance that you’ve received and then can apply it to your own mind in the future. So you internalize that advice.

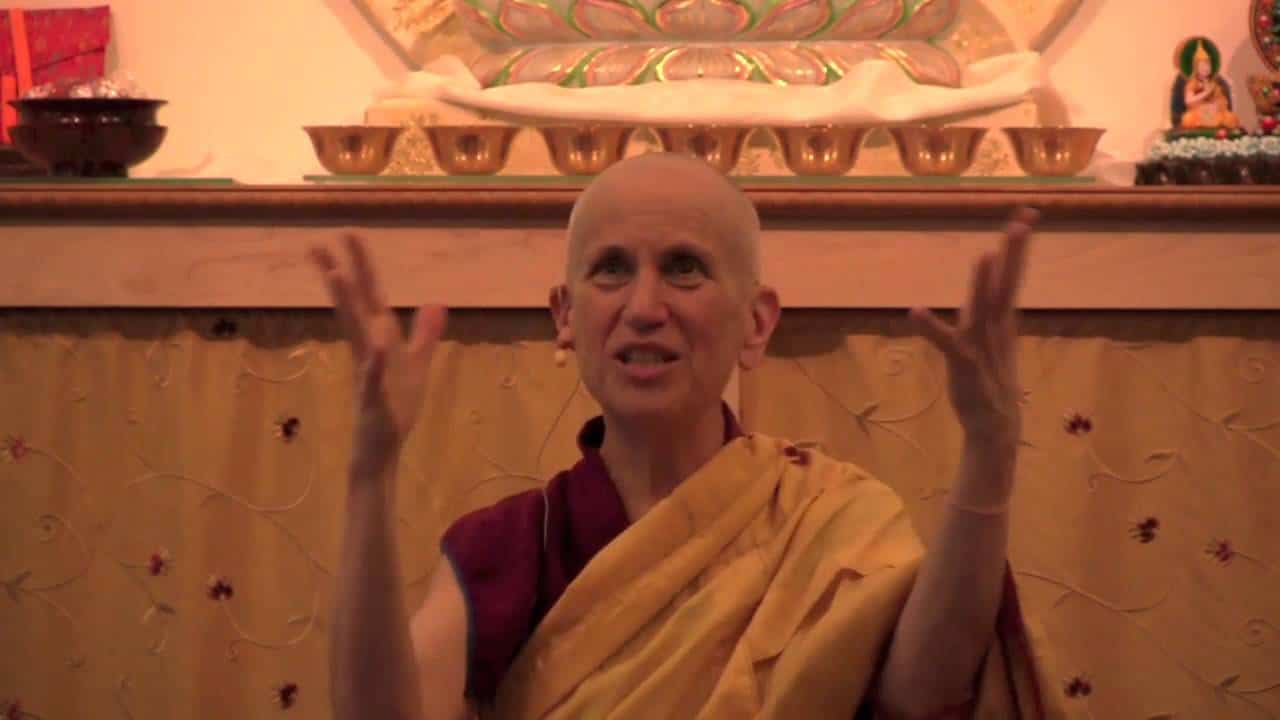

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.