Transforming anger

The third and final installment in a series of three talks given by Venerable Thubten Chodron at Vihara Ekayana Buddhist Centre in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Changing our reaction to anger

We are here for our third installment of hearing about how to work with anger. I’m hoping and I’m wondering if you’ve been thinking about what we’ve talked about the last few evenings. Try to become more mindful of anger when it is arising in yourself. See the faults of anger, and then start to counteract the anger.

It’s very important to understand that I’m not saying we shouldn’t get angry. Whether we get angry or not, it’s not a question of “should.” If the anger is there, it’s there. The question is, what do we want to do if anger is there? Do you understand the difference? I’m not saying you shouldn’t get angry or that you’re a bad person if you get angry. I’m not saying that.

Anger comes, but then what are we going to do about it? Are we going to open our arms and say, “Anger, you’re my best friend; come on in.” Or are we going to say, “Anger, you’re my enemy because you make all sorts of problems in my life.” That’s the point I’m making: it’s our choice; it’s our decision how we respond to the anger. As we train our minds to see situations in different ways, our perspective on life changes, and that will affect whether anger arises quickly or slowly, often or infrequently.

Last night we talked about blaming and fault. We said that rather than finding somebody to blame, it’s better that everybody in a situation accepts responsibility for their own part and corrects that part. It doesn’t do much good to point the finger at somebody else and tell them they should change, because we can’t control other people. The only thing we can even attempt to manage is ourselves. So, instead pointing at other people, we ask, “How can I look at the situation differently so that I don’t get so angry?”

Ask yourself: “How can I look at the situation differently so that I don’t get so angry?” We aren’t talking about exploding with anger, and we’re not talking about repressing anger. We’re talking about learning to look at it in a different way so that eventually the anger doesn’t arise at all. When we become buddhas, and even before that, it’s possible to get to a point where anger doesn’t arise in our mind. Wouldn’t that be nice? Think about it for a minute. How would it be if no matter what somebody said to you, no matter what they said about you, no matter what they did to you, your mind just didn’t have anger? Wouldn’t that be nice? I think that would be so nice.

People could call me names, they can discriminate, they can do who knows what, but in my mind, I’m peaceful. And then with that kind of peace internally we can think about how to act externally to improve the situation. Doing something with the anger doesn’t mean we just accept the situation and let somebody else do something harmful. We can still stand up and correct the situation, but we do it without anger.

Last night we also talked about some antidotes to criticism. Remember the nose and the horns? If people say it’s true, we don’t need to get angry. If what they say is not true we also don’t need to get angry.

Revenge doesn’t help us

Today I’ll talk a little bit about grudges and resentment. Resentment is a kind of anger that we hold over a long period of time. We really resent somebody. We don’t like something. We’re upset about something and it festers inside of us. We hold the resentment for quite a long time.

Grudges are similar to resentment in that when we hold a grudge we are holding onto anger and often want revenge. Somebody hurt us or somebody did something we didn’t like, so we want to get them back. And we think if we cause them suffering that will do away with our own suffering for what they did to us. Does it? We’ve all taken revenge on people. Does it alleviate your own suffering when you take revenge?

When you cause somebody else pain, do you feel good afterwards? Well, maybe for a few minutes: “Oh, I got them good!” But when you go to bed at night, how do you feel about yourself? Are you the kind of person who rejoices in causing other people pain? Is that going to build your self-esteem? Is that going to make you feel good about yourself? I don’t think so! None of us wants to be the kind of person that rejoices in somebody else’s pain. Seeing somebody else in pain doesn’t really alleviate our own pain at all.

I’ll give you an example. I told you before that I do work with prison inmates. Last year or the year before, I was working with one man who was on Death Row. Does Indonesia have the Death Penalty? Yes? Many States in the United States do, too—I don’t think it does any good at all in stopping crime. But in any case, this one man was on Death Row. His lawyer had a lot of doubt about whether he had really committed the crime. He said he didn’t, but when she looked at the situation there were a lot of things that just didn’t add up. And she explained those to me because I was his spiritual advisor.

She tried to get clemency for him. They turned it down, and then they executed him. HIs lawyer was quite incredible; she really had a has a heart of gold. She came to the execution to offer support to the man who she had been defending. She told me it was her 12th or maybe her 13th execution that she had attended, and so often the jury gives a death sentence thinking it will help the family. They think that if somebody was murdered then the family will feel justice has been done and the family will be able to heal and let go of their anger and their resentment about their relative being killed if the person who did it is executed. But this lawyer told me that she’s been to 12 or 13 executions, and not once has she seen the family feel better after the execution—not once.

This is a good example of how we hurt somebody to get even, thinking that we will feel better, and your experience is that you don’t feel better. I think we can see this if we look at our own lives, too. For the first minute or two we might say, “Oh good! I got even.” But after a while, how can we respect ourselves if we are a person who likes to cause others pain and rejoices at their suffering? Grudges don’t really work.

Sometimes we think, “If I hurt them, then they will know how I feel!” Have you ever heard yourself say that? “I want to hurt them, so then they will know how I feel!” How is that going to help you? How is hurting them going to help you? If you cause somebody pain and they are hurting, are they going to say, “Now I understand how so-and-so feels?” Or are they going to say, “That stupid person just hurt me!” Think about it. Are they going to come around to your side after you inflict pain on them, or are they going to be angrier and more upset and more distant?

It’s like the policy of the U.S. Government. Our national policy is that we’ll bomb you until you decide to do it our way and decide you love us. I can talk about my own country that way. That national policy doesn’t work at all. We’ve bombed Afghanistan. They don’t like us. We bombed Iraq. They don’t like us. It’s not that after you harm somebody they come around and say you’re wonderful. Getting revenge doesn’t really help the situation.

Holding onto anger

What about holding onto a grudge? Holding onto a grudge means we are angry inside. Somebody may have done something a few years ago, or maybe even 20, 30, 40, 50 years ago, and you’re still angry about it. I come from a family that holds a lot of grudges—at least one part of my family. It’s very difficult when there is a family gathering and all the extended family comes because this one doesn’t speak to that one, and that one doesn’t speak to this one, and this one doesn’t talk to that one. So, for example, you’re trying to make a seating arrangement at a wedding, but it’s so difficult because so many people don’t talk to each other.

I remember as a little kid being told not to talk to certain relatives even though they lived nearby, I wasn’t supposed to talk to them, and I was a kid wondering, “Well, why not?” Finally, they explained that it was because two generations ago—in my grandmother’s generation—some of the brothers and sisters had quarreled about something. I don’t know why. But because of that, I wasn’t supposed to talk to these people. I remember as a kid thinking, “Adults are so stupid! [laughter] Why do they hold on to things like this for so long? It’s so stupid!”

It’s interesting that you see this happen on a family level, on a group level, on a national level. Remember when Yugoslavia disintegrated and became several little republics, and they started killing each other? The Serbs and the Macedonians and so on. Why were they harming each other? It was because of things that had happened 300 years ago. None of the people who were fighting were alive, but because of things that happened between their ancestors hundreds of years ago, they grew up thinking that they have to hate certain other groups. That’s pretty stupid, isn’t it? I think it’s just foolishness. Why hate somebody because of what one ancestor did to another ancestor when you and the other person in front of you weren’t even alive? I tell you, sometimes adults are just foolish. It doesn’t make any sense to do that.

But we see that with country after another country. Groups within a country or between two countries will hold grudges, and parents teach their children to hate. Think about it: whether it’s within your family or whatever kind of group, do you want to teach your children to hate? Is that the legacy you want to pass on? I don’t think so. Who wants to teach their kids to hate? Whether it’s hating a relative or hating somebody from a different ethnic, racial or religious group, why teach your kids to hate? It doesn’t make any sense.

When we hold onto a grudge, who is the person that’s in pain? Let’s say something happened between you and your brother or your sister 20 years ago. So, you took a vow after that happened: “I am never going to speak to my brother again.” When we take the five precepts to the Buddha, we renegotiate those. [laughter] You take marriage vows, and you renegotiate those. But when we vow, “I am never going to speak to that person again,” we keep that vow impeccably. We never break it.

In my family it happened. In my parent’s generation, some of those brothers and sisters quarreled over I don’t even know what, and they hadn’t spoken to each other for I don’t know how many years. One of them was dying and so their kids called my generation and said, “If your parents want to talk to their brother, they should call now because he’s dying.” And you would think when somebody is on their deathbed, you would at least call and forgive them. No. I think that is so sad. It’s so sad. Who wants to die hating somebody? And who wants to watch somebody you once loved die with you hating them? For what purpose?

When we hold onto anger for a long time, the person who is primarily hurt by it is us, isn’t it? If I hate and resent somebody, they may be off on a vacation and enjoying themselves with movies and dancing, but I’m sitting there thinking, “They did this to me. They did that to me. How can they do this? I’m so mad!” Maybe they did something to us one time, but every time we remember it, every time we imagine the situation in our mind, we do it to ourselves again and again.

All this anger and pain is often our own creation. The other person did it once and forgot about it, and we are stuck in the past. It’s so painful to be stuck in the past because the past is over. Why hold on to something in the past when we have the choice to create a good relationship with somebody now? Because I think what we really want in the bottom of our hearts is to connect with other people, and to give love and to be loved.

Forgiveness doesn’t mean forgetting

I often tell people if you want to cause yourself pain, holding a grudge is the best way to do it. But who wants to cause ourselves pain? None of us do. Releasing the grudge means releasing the anger, releasing the bad feelings. That is my definition of forgiving. Forgiving means I’ve decided that I’m tired of being angry and hateful. I’m tired of holding on to pain that happened in the past. When I forgive somebody, it does not mean I’m saying what they did was okay. Somebody may have done something that was not at all okay, but that doesn’t mean I have to be angry at them forever, and it doesn’t mean I have to say what they did was okay.

An example is the Holocaust that happened in Europe during World War II. They can forgive the Nazis, but we are not going to say what they did was okay. It was not okay. It was abominable. While some people say, “Forgive and forget,” there are some things we should not forget. We don’t want to forget the Holocaust because if we forget it, in our stupidity we may do something similar again. So, it’s not, “Forgive and forget.” It’s, “Forgive and get smarter.” Stop holding on to the anger, but also re-adjust your expectations of the other person.

For example, if somebody did something very nasty to you, you may decide that you are tired of being angry. But you are also going to realize: “Maybe I’m not going to trust this other person as much as before because they aren’t so trustworthy. Maybe I got hurt because I gave them more trust than they could bear.” That doesn’t mean it’s our fault. The other person still may have done something that is completely unacceptable. We have to adjust how much we trust them over different issues. In some areas we may trust somebody a lot, but in other areas we may not trust them because we see they are weak in those areas.

We can stop being angry, but we learn something from the situation and avoid getting into that kind of situation again with that same person. For example, let’s take a case of domestic violence with a man beating a woman; does the woman just say, “Oh, I forgive you, dear. I have so much compassion. You can stay at home. You beat me last night, but I forgive you. You can beat me again tonight.” [laughter] That’s not forgiveness; that’s stupidity. [laughter] If he’s beating you, you get out of there. And you don’t go back. Because you see that he is not trustworthy in that area. But you don’t have to hate him forever.

It’s these kinds of things that are a way of learning from situations. Sometimes when I talk about forgiveness, because I think people really do want to forgive, sometimes they’ll say, “I really want to forgive, but it’s really hard because the other person hasn’t accepted any of the responsibility for what they’ve done to me. They hurt me so much, and they are completely in denial about how much they hurt me.” When we’re feeling like that, it may be true and they may be in denial, but we’re sitting there holding on to our hurt saying, “I can’t forgive them until they apologize to me. First they apologize, then I’ll forgive.”

In our mind we have constructed the scene of the apology. [laughter] There’s the other person down there groveling on the floor on his hands and knees saying, “I’m so sorry I caused you so much pain. You were in such torment. Please forgive me for what I did. I feel so terrible.” Then we imagine we’ll sit there and say, “Well, I’ll think about it.” [laughter] We imagine this kind of scene where they apologize, don’t we? Then finally we say, “Well, it’s about time you realized what you did, you scum of the earth.” [laughter] We have the whole scene imagined. Does that ever happen? No, that doesn’t happen.

The gift of forgiveness

If we make our forgiving conditional on the other person’s apologizing, we are giving up our own power. We’re making it depend on them apologizing, and we can’t control them. We just have to forget about their apologizing because their apologizing is actually their business. Our forgiving is our business. If we can forgive them and release our anger, then our own heart is peaceful whether they’ve apologized or not. And would you want to have a peaceful heart if you could? We would, wouldn’t we? And who knows if the other person will ever apologize?

I’ve had situations that happened years ago, and I’ve tried to make overtures to reestablish at least a friendly relationship, but from the other person there was no response. What to do? What to do is just leave them alone. I’ve also had other situations where people have been very angry at me and I’ve released any bad feeling I had about them and had forgotten about the situation, and then years later they write me a letter saying, “I’m really sorry about what happened between us.” And to me, it’s funny that they’re apologizing because I forgot about it a long time ago. But I rejoice that they are able to apologize, because when they apologize they feel better. It’s the same way when we apologize to other people—we feel better.

But our apologies need to be sincere. Sometimes we just say “sorry” to manipulate the other person and get what we want, but we’re not really sorry. Don’t make those kinds of apologies because pretty soon that other person is not going to trust you. If you keep saying you’re sorry but then you keep doing it again, after a while that person is going to think, “This person’s not very reliable.” It’s better to make a sincere apology and follow through with it. Apologies just with the mouth don’t mean much, and other people can tell when our apology is sincere or when we are just saying it to manipulate.

Forgiving somebody is actually a gift we give to ourselves. Our forgiveness doesn’t matter to the other person. It isn’t so important for the other person because each of us has to make peace with the situation in our own minds. So, just as I’m not going to wait for somebody else to apologize to forgive them, they don’t have to wait for me to forgive them to apologize. Apologizing is something we do for ourselves when apologizing to somebody that we harmed. Forgiving is something we do for ourselves when apologizing to somebody who has harmed us. Our forgiving and our apology often helps the other person.

Betrayal of trust

I want to talk a little bit about when trust is betrayed. When we’ve trusted somebody in a certain area and then that person has acted in the exact opposite way, then our trust is destroyed. And sometimes it’s very painful when our trust is destroyed. But let’s flip it. Have any of you ever done something that has destroyed other people’s trust in you? “Who me? Oh I don’t do that! [laughter] I don’t hurt anybody else’s feelings, but they betray my trust. And nobody has ever felt the kind of pain I experienced because I trusted this person with my own life and they just did the opposite.” Right? We’re sweet. We never hurt other people’s feelings or betray their trust, but we feel like they do a lot of it. It’s quite interesting. There are all these people who have had their trust betrayed, but I don’t meet many people who have done the betraying of trust. How does this happen? It’s like many people catch a ball but nobody throws it.

I have a friend who teaches conflict mediation, and often when teaching he’ll ask, “How many of you are ready to reconcile?” Everybody in the class raises their hand: “I want to reconcile and I didn’t intend for this situation to happen at all.” Then he says, “Why isn’t there reconciliation?” And all these people say, “Well, because the other person is doing this, and this, and this, and this…” Then he comments, “It’s so interesting. All of the people who come to my conflict mediation courses are the people who are so agreeable and kind, who want to reconcile. But all the mean, nasty people who are unreliable never come to my course.” Are you getting what I’m saying?

It’s very helpful for us to look inside and to think of times when we betrayed other people’s trust, and then to apologize if we need to or when we are ready to. It will help us, and it will help the other person. Similarly, when our trust has been betrayed, instead of waiting for the other person to apologize, let’s try and forgive. And, then let’s adjust how much trust we can give to the other person since we have learned something about them from the present situation.

That really makes us step back and think: “How do we create trust in relationships?” Because trust is really important. Trust is the foundation of a family. Trust is the foundation of people living together in society. Trust is the foundation of national cohesion. It makes us think: “How can I become a more trustworthy person?” Have you ever asked yourself that question? Have you ever actively thought about that? How can I be a more trustworthy person? How can I let other people know that I am trustworthy? How can I bear the trust that they have given me and not betray it?

When others betray our trust, that’s karma coming around. We give certain energy out in the universe, and then it boomerangs towards us. When we are untrustworthy our feelings get hurt because other people betray our trust. The question then becomes: “How can we be more trustworthy ourselves?” The question is not “How can I control other people better and make them do what I want them to do?” That’s not the question. Because we can’t control other people and make them do what we want them to do. The question is “How can I be more trustworthy, so that I don’t create the karma to have my trust betrayed and to experience the pain of that? How can I, out of care and compassion for others, be more trustworthy so that others don’t experience pain because of my bad actions and my selfishness?”

So often when we betray other people’s trust, we are basically doing something when there has been a spoken or unspoken agreement between us not to do something. We’ve done it without any care about the effect of our actions on other people. That is self-centeredness, isn’t it? It’s mostly a selfish action. It’s important to own that and to figure out how to improve so that we don’t do that again.

These topics that we’re talking about now may be stirring up a lot in you and making you think of things that happened in the past. But this is good because hopefully if you think about these things with clarity and kindness and compassion, you will be able to reach some internal resolution about them. You won’t carry these things around for years and decades and so on. If something gets stirred up, that doesn’t mean it’s bad. See it as an opportunity to really work out some things so that you can have a more peaceful heart and live with other people in a more peaceful way.

We all do confession and repentance ceremonies, don’t we? These are where people do a lot of bowing and reflection to purify negative karma. Thinking about these kinds of issues that we’re talking about is very helpful to do before those repentance ceremonies because that makes our repentance much more sincere. You don’t have to wait until just before a repentance ceremony to clean up these things. It’s better to clean up these messy emotional things in your heart right now and then do your own confession and repentance in your meditation. That helps to clear these things out. It’s very effective. In Tibetan Buddhism we do purification and confession practices every day. We create negative karma every day, so we do these practices on a daily basis in order to keep on top of what has happened recently and in order to clean up things that had happened in the past.

Jealousy won’t lead to happiness

Another topic is envy and jealousy. [laughter] Oh, I see I pushed some buttons already! [laughter] There can be a lot of anger when we envy other people, when we’re jealous of other people. We always say, “May all sentient beings have happiness and its causes. May all sentient beings be free of suffering and its causes.” But…[laughter] not this person I’m jealous of! “May this person have suffering and its causes and may they never have happiness and its causes.”

Here we are back at revenge again. It isn’t helpful at all, is it? Jealousy is so painful. I think it’s one of the most painful things, don’t you? When you’re jealous of someone—ugh, it’s just awful. Because our mind is never at peace. The other person’s happy and we hate them for being happy, and that’s so contradictory to the kind of good heart that we are trying to develop in our spiritual practice. Depriving somebody else of their happiness because we’re jealous of them also doesn’t make us happy.

Well, you might be happy for a few minutes, but in the long run you won’t. People say to me, “But somebody else is with my husband or my wife now. I’m jealous and mad at them.” Or they’ll say, “I’m mad at them, and I’m jealous of the other person they’re with. I want them both to have suffering.” That’s a pretty painful state of mind. What that state of mind is saying is: “My spouse is only allowed to have happiness when I’m the cause of it. Otherwise, they aren’t allowed to be happy.” In other words: “I love you, which means I want you to be happy, but only if I’m the cause of it. Otherwise, I don’t love you anymore.” [laughter]

Jealousy can also happen in Dharma centers. Sometimes we are jealous of the people who are closer to the teacher. “The teacher rode around in my car. [laughter] Did he ride in your car? Oh, that’s too bad.” [laughter] So, we’re trying to make the other person really jealous of us. Or we’re really jealous because the teacher rode in their car instead of our car. It’s so silly, isn’t it? At the time it’s happening it seems like it is so big and so important. But when you look back on it later it seems so trivial. It’s so silly. What does it matter whose car somebody rode in? Does that make us a good person because somebody rode in our car? Does it make us a bad person because they didn’t ride in our car? Who cares?

Jealousy is very painful. It’s based on anger, and we want to release it if we are going to be happy. The antidote to jealousy is to rejoice in the other person’s happiness. You’re going to say, “That is impossible. [laughter] How can I rejoice in the happiness of my spouse when they are with another person? How is that possible? I can’t rejoice.” But think about it—maybe you can.

If your husband goes off with somebody else then she gets to wash his dirty socks. [laughter] You’re not really losing anything. There’s no need to be jealous. It doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. Let’s wish other people well and heal ourselves and go on with our own life, because if we hold on to this jealousy and this resentment for years then we are the ones who suffer. We are the ones that are in pain. In the context of a marriage, it’s also very bad for the children if one parent holds a lot of resentment against the other parent.

Of course, if you were the parent who was unreliable, you’ve got to think about your actions and not only how they affect your spouse but how they affect your kids. Kids are sensitive to this kind of thing. I’ve met a number of people who have told me, “When I was growing up my dad was having one affair after another.” And of course, Dad thought the kids had no idea that he was cheating on Mom. The kids knew it. What does that do to the respect your children have for you if they know you are cheating? How is that going to affect your children’s relationship with you? It’s not just a matter of hurting your spouse by cheating. That’s a matter, really, of hurting the children.

I think most parents love their kids and don’t want to hurt their kids. It’s something to really think about, and a reason not be so impulsive, not to run after instant pleasure that comes from having a new partner. Because in the longterm, so often it doesn’t work. Then you are left with one spouse who is hurt, your boyfriend or girlfriend who is hurt, and your kids who are hurt. It was all because of seeking one’s own selfish gratification. So, it’s important to think beforehand, and to really consider the effects of our actions on other people.

When we are jealous, release it and move on in your life. Don’t stay hooked to the jealousy because it’s very painful. We have a life to live. We have a lot of inner goodness, so there is no sense staying stuck in the past about something that happened.

Negative self-talk

I want to talk about anger at ourselves. Many of us get very angry at ourselves. Who gets angry at themselves? Oh okay, there are only ten of us. The rest of you never get mad at yourself? Sometimes? In Dharma practice one of the things that impedes people’s meditation and impedes their Dharma practice the most is self-loathing and self-criticism. Many people suffer from self-criticism, self-denigration, shame, and feeling bad about themselves. Often it comes from things that happened in childhood—maybe things adults said to us when we were little kids when we didn’t have the ability to discern whether what they said was true or false, so we just believed it. As a result, we have a lot of self esteem issues now, or we feel we are somehow incompetent, or we’re defective, or we do everything wrong.

When you get really focused in your meditation when you do retreat, you begin to notice how much inner dialogue we have that is self-critical. Have any of you noticed that at all? You notice that every time you do something that doesn’t meet with your own standards, instead of forgiving yourself, you think, “Oh, I’m so stupid for doing that,” or “Leave it to me—I’m such a jerk; I can’t do anything right.” There’s a lot of this kind of self-talk that goes on. We don’t say it out loud in words, but we think it: “I’m insufficient. I’m not as good as everybody else. I can’t do anything right. Nobody loves me.”

We have a lot of those kinds of thoughts going on in our mind. I think it’s very important to recognize them and then ask, “Are they true?” When we get in this state of mind that says, “Nobody loves me,” let’s ask ourselves: “Is it true that nobody loves me?” I don’t think that is true about anybody. I think every single person has many people who love them. Often, we can’t see other people’s love. We don’t let their love in. Often, we want them to express their love one way, but they express it in another way, but that doesn’t mean nobody loves us. And it doesn’t mean we are unlovable.

When we really stop and look, there are many people who care about us. I think it’s important to acknowledge that and let go of that incorrect thought that says, ‘Nobody cares about me,” because it’s just not true. Similarly, when we make a mistake we might beat up on ourselves: “I’m so terrible. How could I have done that? I always mess up every situation. It’s always me who makes a mistake. I can’t do anything right.” When you hear yourself thinking like that, ask yourself, “Is that true?”

“I can’t do anything right”—really? You can’t do anything right? I’m sure you can boil water. [laughter] I’m sure you can brush your teeth. I’m sure you can do some things well at your job. Everybody has some skills. Everybody has some talents. Saying, “I can’t do anything right,” is totally unrealistic, and it’s not at all true. When we see that we’re having a lot of self-blame and self-hatred, it’s really important to notice that and really stop and ask is that true? When we really look and examine, we see it’s not true at all.

We all have talents. We all have abilities. We all have people who love us. We can all do some things very well. And so, let’s accept our good qualities, and let’s notice what is going well in our life and let’s give ourselves credit for that. Because, when we do that then we have a lot more confidence, and when we have confidence then our actions tend to be much kinder, more compassionate and more tolerant.

Developing love and compassion

The last thing I want to talk about is love and compassion—what they mean and how to develop them. Love simply means wishing somebody to have happiness and its causes. The optimum kind of love is when there are no conditions attached. We want somebody to be happy simply because they exist. Very often our love has conditions: “I love you as long as you’re nice to me, as long as you praise me, as long as you agree with my ideas, as long as you stand with me when somebody else criticizes me, as long as you give me gifts, as long as you tell me I’m smart and intelligent and good looking. When you do all those things, I love you so much.”

That’s not really love. That’s attachment because as soon as the person doesn’t do those things, we stop loving them. We really want to discern the difference between “love” on one hand and “attachment” on the other hand. As much as we can, we need to release the attachment because attachment is based on exaggerating someone’s good qualities. The attachment comes along with all sorts of unrealistic expectations of other people, and when those expectations aren’t fulfilled, we feel disappointed and betrayed.

When we train our mind to love somebody, we want them to be happy because they exist. Then we become much more accepting, and we are not so sensitive to how they treat us. In your meditation, it’s helpful to start with a person that you respect, not a person you are attached to and close to. Start with a person you respect, and think, “May that person be well and happy. May their virtuous aspirations be fulfilled. May they have good health. May their projects be successful. May they develop all of their talents and abilities.”

You start with somebody who you respect and you think those kinds of thoughts and imagine that person being happy in that way, and it feels really nice. Then go to a stranger, somebody that you don’t know, and think how wonderful it would be if they were happy, if all their virtuous aspirations were fulfilled, if they had good health and happiness and good relationships. You can add to this—other things that you wish. They don’t have to be just things for this life:“May that person attain liberation. May they have a good rebirth. May they quickly become a fully enlightened Buddha.”

So, really let your heart develop that kind of love for strangers. Then you do this for people you are attached to—people you are close to, maybe family members or very close friends—and you wish them well in that same way but not with attachment. Pull back the mind of attachment and wish that person well no matter what they do in life or who they are with or whatever.

After you’ve done the person you respect, a stranger, and somebody that you’re attached to, then you go to a person that you don’t like or you feel threatened by—a person who’s hurt you, whom you don’t trust—and wish that person well. Extend some loving kindness to that person. At first, the mind says, “But they’re so awful!” But think about it: that person isn’t inherently awful. They’re not an inherently bad person; they’ve just done certain actions that you don’t like. Somebody doing actions that you don’t like doesn’t mean they are a bad person. We have to differentiate the action and the person.

That person who you don’t like, the person you don’t trust who hurt you—why did they do that? It’s not because they are happy; it’s because they’re miserable. Why did that person mistreat you? It wasn’t that they woke up in the morning and said “Oh, what a beautiful day out. There is fresh air and I feel so happy. I feel so fulfilled in my life. I’m going to hurt somebody’s feelings.” [laughter] Nobody hurts somebody else’s feelings when they’re happy. Why do we do things that hurt others? It’s because we’re suffering. We’re miserable, and we mistakenly think that doing whatever it is that we did that hurt the other person will make us happy.

In the same way, when other people have hurt us, it’s not that they intentionally do it. It’s because they are unhappy and miserable. If we wish them to have happiness, it’s the same as wishing them to be free of the causes that made them do what harmed us. Because if they were happy they would be a completely different person, and they wouldn’t be doing the kind of things that we find distressing. Actually, we need to wish our enemies well.

So, you meditate in that way. Start with the person you respect, then a stranger, then one you’re attached to, then an enemy, and then also extend some love to yourself. Not self-indulgence but love: “May I too be well and happy. May my virtuous aspirations be successful. May I have a good rebirth, attain liberation and full awakening.” You extend some loving kindness to yourself. We are all valuable people. We deserve to be happy. We need to be able to extend some loving kindness to ourselves. From there, we spread it out to all living beings—first human beings, then we could add animals, then insects and all sorts of other living beings.

It’s a very powerful meditation, and if you make it a habit to do this meditation on a regular basis—every day even if it’s just for a short time—your mind will definitely change. It will definitely change, and you will be much more peaceful, much happier. Of course, your relationships with other people will also be better. You will create much more good karma and much less negative karma, which means you’ll have more happiness in future lives, and your spiritual growth will be successful. It’s very valuable to do this meditation on loving kindness often.

Questions & Answers

Audience: Every day we experience stressful work situations with co-workers and our bosses; every day we deal with people who don’t like us. How can we be peaceful in our daily work? I’ve experienced a lot of problems in my mind. I cannot solve any problem if my mind gets stressed or mad. [laughter]

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): The question is: “How do we get everybody to do what we want them to do?” [laughter] Are you sure that’s not the question? [laughter] Are you sure? [laughter] “Why do we meet so many obnoxious people? Who created the cause to meet obnoxious people?” This is what I’ve talked about the last few nights. This is our own karmic creation. So, the solution is we need to change and start creating different karma. People harming us is not only due to our own karma. It’s also due to how we interpret other people’s actions.

When we are in a bad mood, we meet so many rude, obnoxious people, don’t we? When we’re in a good mood, somehow they all evaporate. Even if they give us some feedback about a mistake we made, we don’t see it as criticism. But when we’re in a bad mood and when we’re suspicious, even when somebody says, “Good morning,” we take offense. “Oh, they say good morning to me; they want to manipulate me!” [laughter] This is all coming back to our own mental state. Who creates the karma? Who is picking out the sense data and interpreting it in certain ways? This is all coming back to our own mind.

Audience: (A question is asked in Indonesian about someone who is responding to kindness by being difficult. The audience member wants to know how to make them respond differently.)

VTC: This is the same question. How do we make someone do what we want them to do? Just be kind. If that person throws out spiteful, hateful words, it’s like a fisherman casting a line—you don’t have to bite the hook.

Translator: She has been very kind. She is practicing loving kindness, but…

VTC: She still wants that person to change and he isn’t changing. This is the same question, you see? [laughter]

Audience: How can I make that person stop hating me?

VTC: You can’t. [laughter]

Audience: But the condition in the office is getting worse.

VTC: You cannot make that person stop hating you. If the condition in the office is something you find really distasteful, then you go to your manager, your boss, and explain the situation. Ask your boss to help you. If your boss can’t help you and the situation is still driving you crazy, then look for another job. And if you don’t want to look for another job then just bear the difficulty of being there.

Translator: Actually, she went to the boss and told him the situation. But her boss…

VTC: Doesn’t want to help? Then how am I supposed to solve your problem? [laughter] I can’t solve your problem. Either you bear the situation or you change it. That’s it.

Translator: She wanted to quit but her boss disagreed.

VTC: That doesn’t matter. If you want to quit, quit. [laughter] You don’t need your boss’s permission to quit, and you don’t need my permission to quit. You can just do it!

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: That depends on you and what you want to do. If you don’t feel comfortable being around the person, keep some distance.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: This is her question. [laughter] This is his question! [laughter] It’s the same question! Isn’t it? It’s the same question: “How can we make other people different?” No one is asking me, “How can I change my own mind?” That’s the question you need to ask: “How can I change my own mind?” [laughter]

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: I’m not being direct and frank like this in order to be mean. I just know from working with my own mind, how sneaky our self-centered thoughts are. The real questions are always: “How do I work with my own mind?” and “How do I make peace in my own mind?” That’s always what it comes down to. That is what is empowering to us. Because we can change our own mind. Other people’s behavior we can influence, but we can’t change.

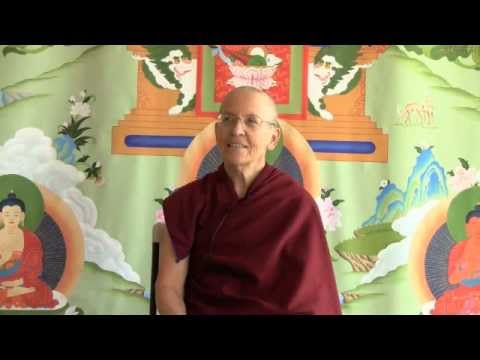

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.