Helping angry people

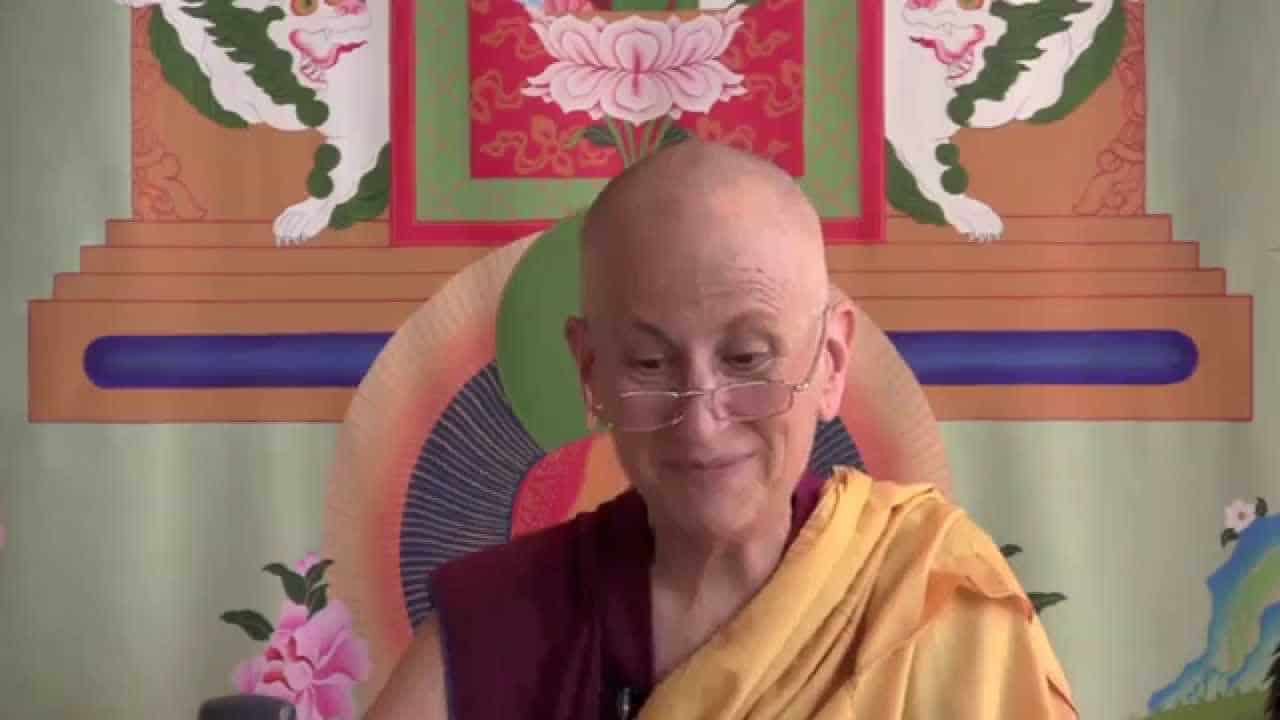

Venerable Chodron discusses changing our perspective when dealing with angry people for the Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner.

I just got back from a two-week trip. I was in Chicago, in Cleveland, and then in Mexico in Cozumel, Mexico City, Puebla, and Jalapa—all in two weeks. I thought I’d just share something that came up in the course of the teachings in Mexico. I was asked to speak on Shantideva’s Chapter Six from Engaging in the Bodhisattvas Deeds. It’s the chapter on working with anger and developing fortitude.

This question comes up a lot in that kind of context, because many people see anger as a problem and they raise their hand and they say, “My husband, my wife, mother, father, brother, sister, employer, employee, pet frog, pet pig, my friend—somebody I know has this horrible problem with anger. How can I help them?”

So, from the side of these people, they really want to help their friends. They see their question as a compassionate question of how they can help somebody with a problem they have. It’s not a question that is easy to answer because we cannot control other people. The one thing that’s so problematic for people when they ask “How can I help somebody” is that they think I will give them the one perfect method to make the person who has a problem with anger change. And of course, I can’t say that or give the one perfect method that will change somebody else’s mind. And even if I did, because Shantideva’s methods are all perfect things, somebody else being receptive is a totally different ballgame.

Many times people are just not receptive to the advice that we have to give them. In fact, they don’t want our advice. And they will let us know in very clear terms that they don’t want our advice. But what happens then is that it’s very frustrating for us because we see somebody’s hurting. We see that they’re confused. We want to help, and we can’t because they’re not receptive at that particular moment. The big understanding we come up with in this situation is that we cannot control other people, yet we think somehow, because these other people are so close to us, we should be able to control them. Of course, we may not use the word “control.” We may have the idea that we should be able to make the right argument, and they will see it makes sense and then do what we say. But that boils down to controlling. Of course, we can’t control anybody else.

It’s very frustrating for us. And this is one way in which we really need to practice Dharma—to realize that the only person we can possibly control is ourselves. We can’t control anybody else. As my mother would say, “Don’t knock your head against the wall.” We can influence other people. We can encourage other people. But we cannot make anybody else change. And then getting frustrated about our inability to make somebody else change only makes us more miserable and makes us angry at them because they’re so dumb that they don’t take our wonderful, fantastic, sage advice that would definitely solve their problem. Right? We live so often with this kind of frustration.

We feel like we’re compassionate people, but I think somehow we’re out of sync here. What we have to come back to is first understanding our own mind, how our own mind works. In this case, what are our own blocks to developing fortitude? Why is it that we hang on so much to our anger and hatred even though it makes us miserable? And we get to know ourselves by understanding our own mind, too.

This would involve us also understanding why we haven’t listened to other people’s wise advice about how we should change. And so, developing this kind of understanding of ourselves makes it much easier to understand and accept where other people are. And then we can accept that people are at where they’re at. That doesn’t make them wrong. It doesn’t make them bad. It doesn’t mean our advice is wrong or bad or ill-suited. It simply means that they’re not receptive at this moment, and what they need is something else. And very often in this situation, what they need is space. A lot of people need to learn by making the mistakes themselves and then figuring out that they need help.

I know for me this has been the case many times in my life that if somebody just says “do this,” and I don’t understand why, or if I feel like they’re criticizing me when they give the advice, then immediately I shut down and stop listening. And it’s only when I fall down that I realize that I could have used some tips while walking about how to keep walking without falling down. But it’s only after you fall down that you realize you needed help. While you’re still managing—even though not very well—you often think you don’t need help.

My point here is that first of all, we need to focus on ourselves, on helping ourselves and understanding how our own mind works. Second, we need to accept where other people are at and that they may not be where we would like them to be. And we should try not to put any judgment of good, bad, or otherwise on it. They just are who they are. They’re at where they’re at. And our job is to keep the door open.

Third, we need to avoid getting frustrated because we can’t control the world. Because here what we’re bumping up against, again and again, is our own self-grasping ignorance. It’s this idea that there is a big me who’s in control, and it’s our self-centered thought which thinks that what I have to say is obviously the best thing for the other person, and that they should take it to heart immediately, and they should thank me profusely for the help I’ve given them. We need to recognize that our compassion and our wisdom—what we think of and what we’re saying to this person—has actually been contaminated by self-grasping ignorance and the self-centered mind.

We need to come back to accepting what is without getting discouraged—being able to keep the door open for when the person later on decides that they need help or when they later on understand what we said. Because if we get frustrated and angry that just destroys our virtue, and it ruins the relationship with the person who we’re trying to help. Does this make some sense? I learned this through knocking my head on the wall a lot.

We think the argument or advice is inherently right for everybody. And here’s where you see the Buddha’s skill as a teacher. He may see that argument is really true and valid, but it’s not necessarily the right advice for this individual at this particular time. This is why the Buddha is such a fantastic teacher—because he doesn’t give everybody the same advice at the same time. He really knows that people have different ways of thinking and different dispositions, and they need to be dealt with in different ways.

Audience: So, you’re saying that your advice is working with the other people? Or your arguments are working with them or what?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Okay, so for the mind that says, “I’m right and why don’t they listen,” I think first it’s a thing of slowing down and really listening to what the other person’s saying. When you really listen with your heart without first thinking about how you’re going to respond, but really listening just to hear where they’re at, then you can sense a little bit where they’re at, what they already believe in, what it is that could be the next step for them, if they’re asking for advice or not, if they’re open to receiving something or not.

And you can also get a sense that, “Gee, they want to continue talking on this topic.” Other times you can sense, “No, I’ve heard enough. Thank you very much. That was interesting. Let’s talk about the baseball scores now.” So sometimes you go on to talk about the baseball scores, and let them do that if that’s what they want. And you do something else. But other times, you might get a sense they’re interested, but when would be a good time to say more or what would be good to say?

Often with people who aren’t Buddhist and very often even with people who are Buddhist, it’s much more skillful to talk in terms of ourselves and tell them what we do. Because most people don’t like being told what they should do, even if our arguments are right, and we know best. Right? It’s much more effective to just say, “Gee, I have this difficulty with anger. And I was reading about this,” or “My teacher said this,” or “I tried this and it kind of helped me. It took a while, but gradually I began to understand this deeper and deeper.” If you talk about yourself, people don’t feel threatened. If you say “you” then many people automatically—before you can say more than “you”—have already shut-down.

I think that listening is a big part of it because sometimes we’re a little bit too eager to help because sometimes our help is more like showing what we know or showing that we’re right. There’s a little bit of that underneath the motivation that kind of corrupts it whereas really listening gives us a lot more information. However, if I keep replaying the thought “Well, I really want to say to them, blah blah blah blah blah,” then obviously that’s not going to be skillful at this moment.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.