The person and the aggregates

Part of a series of short talks given on Nagarjuna's Precious Garland of Advice for a King during the Manjushri Winter Retreat.

- Seeing that the person doesn’t exist within or totally separate from the aggregates

- Understanding the the person cannot be the collection of the aggregates

- Examining how we think we exist

- Fear and anxiety about death

We were talking about this verse from Precious Garland where Nagarjuna said:

A person is not earth, not water,

not fire, not wind, not space,

not consciousness, not all of them.

What person could there be other than these?

The first three lines we’re checking to see: if the person is inherently existent then the person should be findable in the aggregates. But it’s not any of the five elements, and the person is not the consciousness. So we’ve eliminated the person being one with the aggregates. We can’t find the person in the aggregates.

The other option is that the person’s something totally separate from the body and mind. That’s what the last line says: “What other person could there be than these?” If you take all the aggregates, and the person isn’t there, then is there a person somewhere else apart from the aggregates?

Sometimes we have the feeling that, “Yes! I am me, and I am separate from my body and mind. I am this universal emperor who controls the body and mind. And I don’t depend on it at all.” We have this notion like, “Oh, when I die I’ll just be there. The body will decay. The mind will do whatever it does. But I will remain there, steady, peaceful, serene, un-freaked-out.”

Do you ever have that kind of idea of yourself? “There I’ll be, separate from the aggregates, and the aggregates, yes, death, this kind of stuff, but that’s not going to really affect me.”

But then when you look closer at that feeling of an “I,” the way that “I” appears, and then you say, “Well can the person actually exist separate from the aggregates?” Do you know any person that does exist separate from the aggregates, whereby the body and mind are here and the person is over there? Except in Hollywood where anything is possible, do you know of anywhere where the person is separate from the aggregates? Do you really think that there’s a you that at the time of death just kind of floats out of your body and mind—an inherently existent you that is always the same, it’s always you, that you’re in control of because you are you? Is there such a thing like that? That would be a little bit hard to come by, wouldn’t it?

So then we’ve kind of exhausted the two alternatives. We can’t find the person either in the aggregates or we can’t find the person separate from the aggregates. The one thing that we didn’t go into is the last phrase of the third line, when Nagarjuna says, “Not all of them.” Meaning not the combination or the collection of the aggregates.

So let’s go back to that one. Because okay, I’m not my body, individually I’m not the earth element, you know, these kinds of things…. But what about if we got the body and mind together? All the different elements plus the consciousness constituent, we put them all together…. Isn’t that me? Aren’t I the collection?

What is a collection? A collection is just a number of parts put together. None of the parts are the person. If you put a bunch of non-persons together are you going to come up with a person?

[In response to audience] Yes, but something being “mine” and something being “me” are different. Yes? The glasses are mine, but the glasses are not me.

So the collection of the aggregates, are they me? Each of the six constituents: none of them individually are me. How can the collection be me? It’s like having six oranges, putting them together and getting a banana. That’s not going to work.

Then you say, “But, are you sure?” Because part of your mind says, “Well maybe if we arrange all the parts in a specific way that will be me.” Like it couldn’t just be earth element sitting in a pile here, and water element in a bowl over there, and fire element blazing over there, consciousness sitting over here. We’ve got to put them together in a certain way.

But still, if they’re put together in a certain way they’re still a bunch of things that are not people. So in the context of inherent existence it means you have to be able to find some thing that is the person. And even the collection isn’t suitable to be called the person. So then you’re left with … the question he asked then: “What person could there be other than these?” There’s nothing in the aggregates. Also, there’s nothing separate from the aggregates. Those are the only two possibilities, neither of them panned out, so your only conclusion is that the person doesn’t exist inherently, or there’s no inherently existent person. It’s the only conclusion you can possibly draw from that.

That has a really powerful impact on you when you really get in touch…. You know yesterday night I talked about the four-point analysis. If you really get in touch in the first point at really noticing how you think you exist, how the “I” appears, and when you get really aware of that and there’s this feeling of, yes, there’s just me here. And kind of like, “If there isn’t me then what does exist?” So when you have some kind of clear perception of what the object of negation is and how strongly you feel it exists, and that that’s who you are, then when you realize that the person doesn’t exist in any of those ways, then there’s the feeling of, “Oh my goodness, everything I thought…. Everything I’ve based my whole life on isn’t there.” Because if we look all day in and all day out we’re basing our lives on this assumption that there’s a real me. Aren’t we?

Because if there’s a real me then there are things that make me happy so I have a right to pursue them. There are things and people who interfere with my happiness so I have a right to clobber them. There are people who are better than I am so I’m jealous of them. There are people who are worse than I am so I’m arrogant over them. I don’t feel like doing something so I just don’t. The rationale for all the afflictions all center around this idea of there being a findable person there who definitely has to be protected and who is entitled to every happiness in the universe without compromising anything. Right?

When you realize that the conventional person doesn’t exist the way you’ve been apprehending it to exist, then it’s really kind of surprising. But it’s a good kind of surprise because if there’s no inherently existent person there then there’s nobody you have to defend. Which means when somebody criticizes you there’s nobody whom you have to stick up for. Yes? We don’t need to go: [Gasp] “Wait a minute, how can they say that about me? How can they say that to me?” Because we’ll realize that that person that feels so threatened is being misapprehended—we’re holding it as truly existent and it’s not. When we stop holding it as truly existent then we don’t have to defend it. Because when there’s no truly existent person—when you can’t find anything there that’s this solid, concrete thing—then whose reputation are we worried about?

And when we then go on to think about the selflessness of phenomena, what is a reputation anyway? Dissect a reputation. It’s just other people’s opinions. Yes? Of what value? Why am I getting so wonked out about other people’s opinions? Can you even find their opinions? How long does one of their opinions last? Is it permanent? Does it ever change? And then we realize, “What am I getting so upset about?”

And then when you think about death—because what usually freaks you out about it, like, “I’m dying! I’m leaving everything, my whole identity is collapsing around me!” When you realize that the self doesn’t exist inherently like it appears, then again there’s no solid, concrete person that’s going to die. The self only exists by mere designation. There’s nothing findable there, so there’s nobody there that has to freak out at the time of death. Because the self exists as a mere label.

So in this way we begin to see how understanding emptiness can really relieve us of the pain of the afflictions.

None of you look too happy about this. [Laughter] This is because we lack merit. If we really understood how ignorance is the root of samsara then when we hear this we’d be so happy. But we don’t really understand that.

[In response to audience] So when you think about death and you have anxiety because you don’t know what’s going to happen, that anxiety about death—that “freak out” anxiety…. I’m not talking about a wisdom consciousness that can look and say, “Okay I’ve created this kind of karma and that kind of karma and what kind of rebirth am I likely to have and what do I need to do.” I’m not talking about that wisdom mind that looks at it. But when we have those [panicked], “Oh my gosh I’m gonna die and oh what am I going to become?” If we realize that feeling is all based on grasping at a truly existent person, and if that truly existent person doesn’t exist then there’s nothing there to grasp at and there’s no truly existent person who’s going to die. It’s just the aggregates changing.

[In response to audience] Oh, it’ll definitely influence our next rebirth in a very good way, because if we can die with an understanding of emptiness, wow, we might get born in the pure land or get enlightened in the bardo, or who knows what.

[In response to audience] So you’re saying what makes your mind joyful in this is to think that—I’m going to put it in different words—that it’s the afflictions that impede your mind from having compassion, and the afflictions that impede your mind from being open and relaxed. And so when you have this kind of understanding of awareness then the afflictions have nothing to stand on. So then there’s more space in the mind to look at things in a whole variety of ways. And so one of those ways could be a mind with compassion.

And it’s true, you know, when we look…. I mean we all value compassion, we all want to be compassionate. But one of the big obstacles we have to being compassionate is that our afflictions get in the way. You know? “I want to be generous,” but then miserliness comes in the mind. “I want to be kind … but I’m angry!” So we really see how the afflictions that are rooted in this self-grasping really impede compassion as well.

[In response to audience] When you see an affliction arise and say, “This isn’t what I want, this isn’t the kind of person I want to be….” And just being able to catch it…. And see that because you can catch it then it becomes much easier to let go. And that’s definitely a virtuous mental state, isn’t it?

[In response to audience] So sometimes you see an affliction in the mind, one part of your mind feels sad, like, “I don’t want to be that kind of person.” But then when you think of giving it up then you also become sad because, “Who am I going to be without it?” [Laughter]

The mind that says, “I’m sad because I have an affliction in my mind, I don’t want to be like that,” that’s a virtuous mental state. Okay? The mind that’s grabbing on to, “But if I give that up then people will walk all over me,” or you know, whatever our fear is, that’s something else.

[In response to audience] So that isn’t you. Because when you identify with that affliction and think, “That’s me,” then you come back to this meditation and you say, “Is that me?” Because if that affliction is me then that’s who I am 24/7. And if my anger is me then when I say, “I’m walking,” it’s the same as saying, “Anger is walking.” And when I say, “I feel benevolent,” it’s the same as saying, “Anger feels benevolent.” Which is crazy. So you begin to look and say, “If I’m my anger then that’s who I am 24/7.” Is that going to work? Does that even fit the description of who I am? Can’t be.

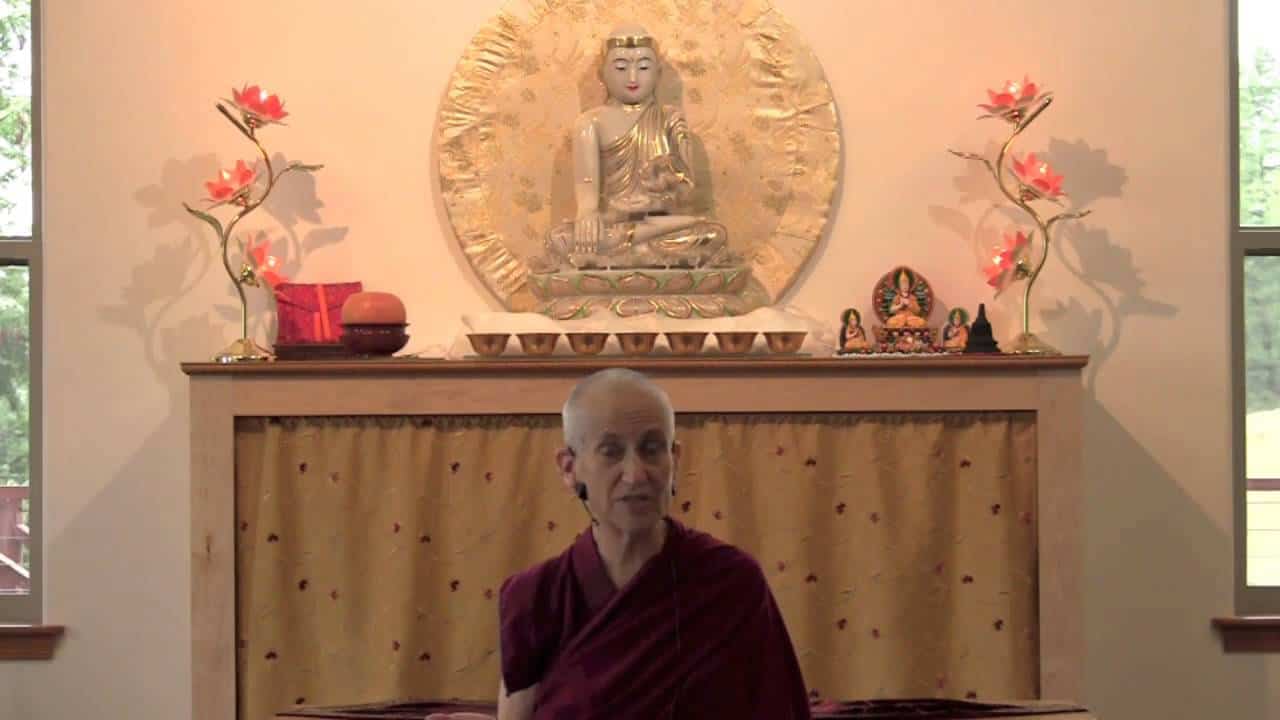

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.