Visit to Airway Heights Correctional Center

On June 2, those imprisoned at Airway Heights Correctional Center celebrated Buddha Day and invited Sravasti Abbey monastics to participate. I volunteered to go, along with two Abbey nuns. I had never been to a correctional facility before and was both excited and nervous to go. During the drive there, we talked about prison etiquette, rules, and security measures to keep in mind.

We arrived early and were greeted at the entrance desk by a security guard who was friendly and welcoming. This was a pleasant surprise, as I expected a stern and cold reception. While waiting for admittance, the chaplain and two other volunteers joined us.

We were politely escorted through security measures and a long corridor. We walked slowly, making sure our visitor badges were visible to the guards. As I entered the prison’s yard, I noticed the tall concrete walls capped with barbed wire. I also noticed an unexpected and well-manicured rose garden, adding a touch of beauty, grace and color to the stark background of bland-colored buildings and fences. Incarcerated people are responsible for the garden’s maintenance and they take great pride in its upkeep, we were told.

While walking to the meeting hall, I focused on my breathing to reduce the anxiety running through my body and mind. I was thinking about how it would feel to be incarcerated, and how it would feel to know there was no getting out.

It occurred to me that, while people in prison are very aware of their confinement, all of us are in a prison we can neither see nor touch: the prison of our ignorance, afflictions and karma. We are all confined by the walls of ignorant conceptions which are even more oppressive than the concrete walls I was looking at. Thinking about these things helped me connect with the experience of incarcerated people.

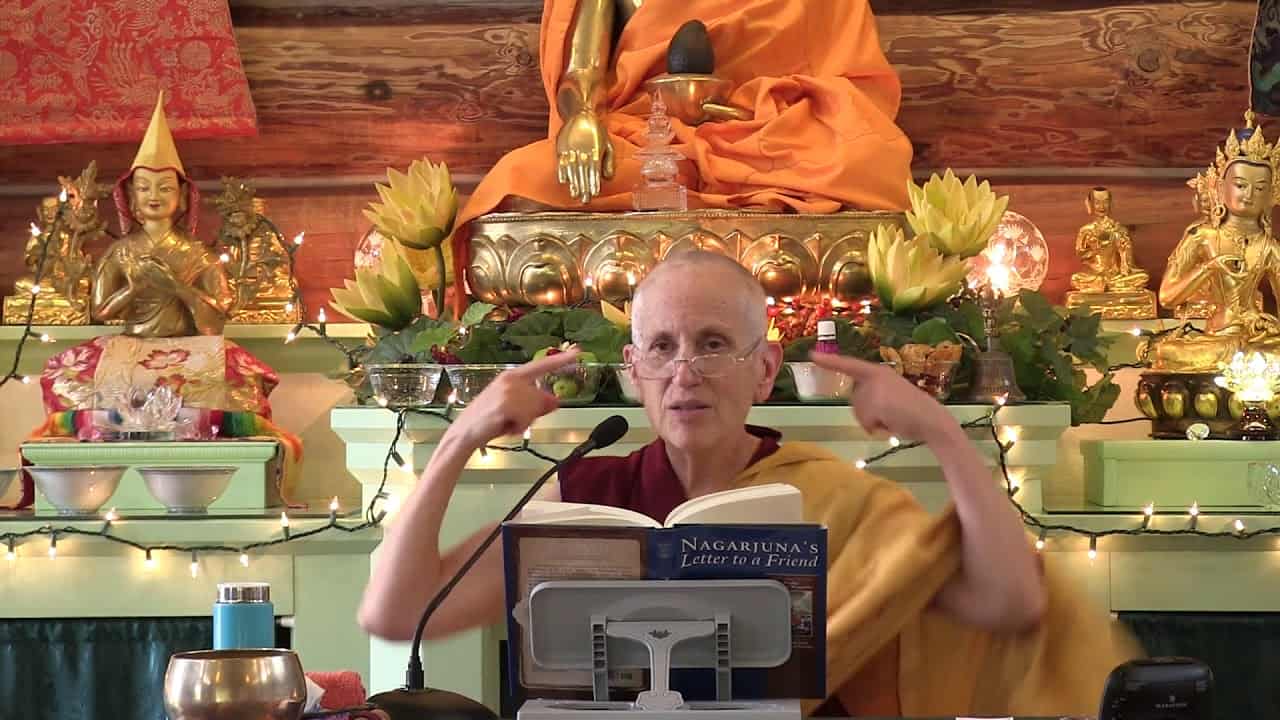

At the hall, about 30 people had gathered. I was impressed by the care and love evident in the rooms’ arrangement. The altar was simple and beautiful, decorated with colorful drawings of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Red Tara, and other holy beings. The drawings were very accurate and seemed to have been made by the incarcerated people. A circle of chairs, each covered with a white cloth, added to the sense of sacredness that permeated the space. In one corner, several people were finishing a mandala made with colored grains of rice.

We bowed to the holy beings and were invited to sit beside the altar. I reminded myself to be present and attentive as a way to honor our hosts’ efforts and their Dharma practice.

The proceedings were lovely and included prayer, chanting mantra, and tsog offering. The incarcerated person acting as master of ceremonies spoke eloquently and his knowledge of the Dharma was inspiring.

We monastics were invited to speak and took turns at addressing the congregation. I was not aware we would give a talk and was unprepared. Just before the microphone was handed to me, I made a silent prayer requesting inspiration, and then spoke about my experience working with anger and the Dharma tools I found most helpful to deal with it. As I spoke, I felt a sense of closeness and friendship toward those in the audience, remembering their kindness and our interdependence.

At the end of the event, many came to shake hands with a smile and words of gratitude and appreciation. I felt privileged to have been there and to have gotten a glimpse of these men’s quest for inner transformation.

Looking back at this experience, I can see that my view of the incarcerated was one-dimensional, tainted by fear, judgment, and labeling. I expected to find hardened criminals, but instead I found human beings who, just like me, want happiness and not suffering. I learned that, when we dehumanize others, we ourselves are diminished; and when we recognize the value and humanity in others, we are restored.

Venerable Thubten Nyima

Ven. Thubten Nyima became interested in Buddhism in 2001 after meeting a tour of monks from the Ganden Shartse Monastery. In 2009 she took refuge with Ven. Chodron and became a regular participant in the Exploring Monastic Life retreat. Ven. Nyima moved to the Abbey from California, in April of 2016, and took Anagarika precepts shortly thereafter. She received sramanerika and shiksamana ordination in March 2017 and full ordination in August 2023. Ven. Nyima has a B.S. degree in Business Administration/Marketing from California State University, Sacramento and a Masters degree in Health Administration from the University of Southern California. Ven. Nyima currently resides in Colombia.