Nine-point death meditation

Verse 4 (continued)

Part of a series of talks on Lama Tsongkhapa’s Three Principal Aspects of the Path given in various locations around the United States from 2002-2007. This talk was given in Missouri.

- Review of the three principals of the path

- The eight worldly concerns

- Reasons to contemplate on death

- How to meditate on death

Three Principal Aspects 06: Verse 4: Nine-point death meditation (download)

In the text on the three principals of the path we were talking about:

- renunciation or the determination to be free from cyclic existence

- the loving compassion and thought of bodhicitta, the altruistic intention

- and the wisdom realizing emptiness

Giving up clinging to the happiness of this life is the first step in generating the determination to be free.

Then in talking about the first one, the determination to be free, we got as far as verse one, two, three, four. In verse four the first sentence, “By contemplating the leisure and endowments,” which I also translate as freedoms and fortunes, “so difficult to find and the fleeting nature of your life, reverse the clinging to this life.” That’s talking about how to develop the determination to be free—the first step being giving up clinging to simply the happiness of this life. When we’re just totally buzzing around our present life’s happiness that’s a huge obstacle towards getting anywhere spiritually. The second sentence, “By repeatedly contemplating the infallible effects of karma and the miseries of cyclic existence, reverse the clinging to future lives.” That’s talking about how to stop craving for good rebirths in cyclic existence and generate the wish to be free altogether.

We’re still on the first sentence—talking about how to give up the obsession with the attractions and pleasures of this life. That becomes a huge obstacle for spiritual practice because it consumes so much time. We’re chasing and running around looking for pleasure wherever we can get it. In the course of looking for pleasure we create a lot of negative actions. These leave negative karmic imprints on our mind which bring about suffering results. So as we chase around, running, looking for own pleasure we actually create a lot of causes for suffering for ourselves.

In seeking just the happiness of this life—that’s what motivates people to kill, to steal, to have unwise sexual behavior, to lie, to use their speech in disharmonious ways, to gossip, to use harsh words, the whole thing. The motivation behind it is my happiness now. That’s the basic motivation with which we live our life at present—my happiness now. And if it can be right now, this very moment, okay! Well at least five minutes from now, and the longest I’ll wait is my old age. So we’ll make preparation for old age even though we’re not sure we’re even going to live that long. We’re just totally involved with the happiness of this life. We don’t think beyond this life, like what happens after we die? Where do we get reborn? We don’t think about a higher purpose to life because we just run around chasing all of our own little ego thrills basically. We cloud it in all sorts of other stuff. But that’s what it boils down to—at least when I look at my own mind. Maybe you people are better off than I am but that’s a description of me.

The eight worldly concerns

We were talking about the eight worldly concerns as being the epitome of happiness for this life. These eight being in four pairs: first attachment to money and possessions, and displeasure at not getting them or losing them. The second is being delighted and happy when we’re praised and approved of, and being miserable when people criticize us or blame us or disapprove of us. The third is wanting a good reputation and a good image in front of other people, and not wanting a negative one. The fourth is wanting sense pleasure: to see good things, hear nice sounds, smell, taste, touch, all these things, and not wanting bad sensual experiences. And so just looking for those—seeking to get the four of those pairs and avoid the other four—is what seeking the happiness of just this life boils down to. That’s how most of us live our life. We create a lot of negative actions in the process of it and make a lot of misery for ourselves and others.

As antidotes to that, as ways to oppose that, and generate the determination to be free, first we thought about our leisure and endowments, or translated as freedoms and fortunes, of a precious human life. (I’m just reviewing now what we’ve talked about the last couple of weeks.) In particular, with our precious human life learning to recognize its qualities; then seeing its purpose and meaning; and then seeing how rare and difficult it is to attain. Then the second part of that, as the first sentence in the fourth verse says: the first part was contemplating the leisures and endowments of our precious human life, and the second part is contemplating the fleeting nature of our life. In the lamrim that’s the meditation on impermanence and death.

That’s what I want to talk about in this talk: impermanence and death, and how we use that to bolster our spiritual practice. This is a very important topic. They say if you don’t remember impermanence and death in the morning, you waste the morning. If you don’t remember it at noontime, you waste the afternoon. If you don’t remember it in the evening, then you waste the evening. So it’s a very important topic.

This topic is the first thing the Buddha taught after his enlightenment. When he taught the Four Noble Truths, impermanence and death is the first topic under that. It’s the last topic he taught too. He illustrated that by his parinirvana—by he also passing away and giving up this body. Now death and impermanence is something that general people in society do not like to think about and do not like to talk about. We have this view that if we think about death it might happen; and if we don’t think and talk about it, it might not happen, right? So we go through life not thinking and talking about it, not making any preparation for it, but it’s the one thing that’s certain to happen.

I remember as a little kid on the highway near where we lived was Forest Lawn Memorial Park. They couldn’t call it a cemetery because that speaks of death too much—so it’s a memorial park. I remember as a little kid driving past that and asking my mom and dad, “Well, what happens there?” “Well, that’s where dead people are.” “Well, what’s death?” “Um, people go to sleep for a long time.” I got the distinct feeling I was not supposed to ask any more questions. We don’t talk about death because it’s too scary and it’s too mysterious. It’s too unknown so we’ll just pretend it doesn’t exist. Yet our life is framed by our own mortality, isn’t it?

We have a calendar full of activities, “Thursday I have to do this and Friday I do that and Saturday I do this, I have so many things in my life and I’m so stressed out. So many things to do.” But if you look at it we don’t have to do any of those things on our calendar. None of them are things we have to do. The only thing we have to do is to die. That’s the only thing that’s definite about our life is that one day it ends. Everything else that we say we have to do, that’s not correct. We don’t have to do it; we choose to do it.

This is really important because in our lives so often, “Oh, I’m so sorry. I can’t practice the Dharma. I have to go to my child’s recital.” “Oh, I’m sorry. I can’t go to this retreat. I have to work overtime.” We don’t have to do any of those things. I think we should be honest and say, “I’m choosing to go to my child’s recital.” “I’m choosing to work overtime.” “I’m choosing to spend my money on this and not on that.” That’s much more honest than saying I have to, which is not really true.

Six disadvantages of not contemplating death

The meditation on impermanence and death has many advantages if we do it; and it has many disadvantages if we don’t do it. Let me talk a little bit about those because it’s important to understand why we do this meditation.

There are six disadvantages if we don’t remember impermanence and death. First one is that we don’t remember to practice the Dharma or to be mindful of it. We just space out, get totally involved in our lives.

Second is, if we do remember the Dharma, we won’t practice and we’ll procrastinate. That’s what I call the mañana mentality: “I’ll do my spiritual practice mañana , today I’m too busy.” So it gets mañana’d all the way until we die and no practice gets done.

The third disadvantage is that even if we do practice, we won’t do so purely. We might attempt to practice but because we don’t remember impermanence and death, our mind still has a motivation for the pleasures of this life: “I’ll go to Dharma class if it’s fun, if it’s interesting, if I can be close to the teacher and get some emotional strokes, if I can get some prestige by going, if I could be famous by learning the Dharma.” Our practice becomes impure if we don’t really purify our motivation through remembering impermanence and death.

The fourth disadvantage is that we won’t practice earnestly at all times. In other words, our practice will lack intensity. We might practice with a good motivation but then we kind of lose it after a while and our practice isn’t intense. We see this all the time. This is the story of our practice, isn’t it? We get really into it, and then after a while it becomes old hat and boring. We do it as a routine but it isn’t vital in our minds anymore.

The fifth disadvantage is that we create a lot of negative karma which will prevent us from gaining liberation. Like I was saying, when we’re just seeking the happiness of this life, because we don’t think about mortality and karma and what comes after that, then we don’t take care with our actions. We do all sorts of unethical actions to get the pleasures of this life, or to retaliate when somebody harms us in this life. And so we create a lot of negative karma which brings suffering.

The sixth disadvantage is that we will die with regret. Why do we die with regret? This is because we’ve wasted our life. We haven’t used it to transform our mind, and instead we’ve just accumulated a lot of negative karmic imprint. So when the time of death comes we die with regret—which I think must be the most awful way to die. Ever since I was a kid I’ve always had the feeling, “I don’t want to die with regret.” Because dying with physical pain is one thing. But dying and looking back at our life and thinking, “I wasted my time.” Or, “I used my energy in harmful ways. I harmed other people and I didn’t repair that.” I think that would be so painful; worse than physical pain is to die with that kind of regret. This all comes from not thinking about mortality. By not thinking about mortality we just get involved in all our selfish worldly concerns.

Six advantages of contemplating death

The advantages: there are six benefits of remembering death and impermanence. First one is that we’ll act meaningfully and will want to practice the Dharma. When we remember death it makes us think, “What are my priorities in life?”That gets us to make our life meaningful and to practice.

Second is, our positive actions will be powerful and effective because they won’t be contaminated by ulterior motivations for this life. We’ll create powerful positive actions of real benefit to ourselves and others.

Third is, remembering impermanence and death is important at the beginning of our practice. In other words it propels us on the path. When we think about our mortality it makes us do reflection on our whole life. We consider, “I’ve lived up until now and when I die, what am I going to have to take with me? What’s been the meaning of my life?” That reflection impels us to make our life meaningful. It gets us going on the path.

Fourth is, it’s important in the middle of the practice. This is because remembering impermanence and death helps us persevere as we’re practicing. Sometimes we go through different difficulties and hardships on the path, everything’s not always pleasant. We practice the Dharma and still people criticize us, and blame us, and talk behind our back, and betray our trust—all sorts of things. In those times we might want to give up our spiritual pursuits because we’re in misery. But if we remember impermanence of death and the purpose of our life, then we don’t give up in the middle of the practice. We realize that these hardships are actually things that we can endure, that they’re not going to overcome us.

Fifth is, remembering impermanence and death is important at the end of the practice because it keeps us focused the beneficial goals. Towards the end of the practice we really have wisdom and compassion and skill. By remembering the changeable nature of things and our own mortality, then we feel really energized to make use of the skills that we have to benefit all beings.

The sixth benefit is that we die with a happy mind. For this reason they say if we remember impermanence and death while we’re alive, and then we practice well, when we die we don’t die with regret. We even die with happiness. They say especially for the great practitioners, when they die, that death for them is so much fun it’s like going on a picnic. This seems unbelievable to us but I’ve seen people have quite amazing deaths.

One story about a monk’s death

I’ll just tell you one story. I have a lot of stories about death but this is one that really made a very strong imprint on me. When I lived in India, the Tushita Retreat Center where I lived was up on a hill. Just underneath the retreat center there was a row of mud and brick houses. About six rooms actually, just single rooms of mud and brick where there were some Tibetan monks who lived. There was one very old monk who hobbled around with a cane. One day it seems he fell over right outside of his hut. The other monks who lived in the other rooms were away doing a puja, a religious service somewhere else. They didn’t see him and one Western woman who was walking up the hill to the Western center, Tushita, saw him there. She ran up to us and she said, “Hey, there’s this monk and he’s fallen down and he can’t get up and does anybody have medical skills?” There were a few us there; there was one woman from Australia who was a nurse. And so she and I and one Tibetan nun went down there. This poor monk was lying sprawled out. We put him on the bed in his room and he started hemorrhaging.

Meanwhile, his Tibetan friends had come back, the monks had come back. They just were very calm about the whole thing. They put a plastic sheet underneath him because he was hemorrhaging so much. They just said, “Okay, we’ll go do our spiritual practice—it looks like he’s dying. We’ll start doing the prayers and things for him.” But the Westerners up at the retreat center, one man heard about this and said, “Oh, I mean we can’t let him die. Death is important.” So he got in the jeep. He took the jeep all the way down the hill because the hospital was quite a ways away. He got the doctor at the hospital; took the jeep all the way up the hill and this is a narrow, one-lane road with a cliff on one side. He got all the way up the hill. The doctor got out and looked at the monk who was hemorrhaging and said, “He’s dying. I can’t do anything.”

It was real interesting for me because the monks just knew it, they accepted it right away. The Westerners, even though they were Dharma practitioners, couldn’t accept it and had to do all this stuff. Anyways, so as he was hemorrhaging and this incredible stuff was coming out of him; they would pull the plastic sheet out and bring it to me. My job was to take it and put it over the side of the mountain. Great job, huh? And then they alternated two plastic sheets to keep underneath him. Then the monks finally said, “Okay, our preparations for the pujas are ready.” This monk had a particular meditation deity that he had practiced most of his life; and so the other monks were going to do the puja, the religious service, of that particular buddha figure. They called me and then maybe one or two other people there into the room and we started doing that practice. The nurse and the Tibetan nun stayed to help this monk who was dying.

They told us afterwards that once everybody left, he said to them, “Please, sit me up in meditation position. I want to die in meditation position.” Since he couldn’t move, they moved his body and got him upright. But he was so weak from all the hemorrhaging that he couldn’t sit upright. So then he said, “Well, just lie me down and put me in the physical position, the posture of my meditation deity.” They did that but his body was too weak to sustain that. (This guy was hemorrhaging and he’s giving them directions on what to do!) Then he said, “Okay, just put me on my right side in the lion position.” This is the position the Buddha lay in when he was passing away: your right hand under your right cheek, and your legs extended, and your left hand on your thigh. They put him like that and he said, “Okay, just let me die now.” He was completely calm, he wasn’t freaked out at all, totally calm. The nurse from Australia wasn’t a Buddhist, she had just been visiting the center. She came out afterwards and said, “I’ve never seen anything like this!” He was completely calm.

Meanwhile the rest of us were doing this puja and we were one or two rooms down. It took us several hours, maybe three or four hours to do it. When we were done we came out. One of the monks who was at the puja was a friend of this monk who was dying. So again, their friend is dying: they’re completely calm, no big crisis, no big problem. This monk’s name is Geshe Jampa Wangdu. I remember him quite well. He went into the room where this other monk had died. There are certain signs in the body that indicate whether somebody is going to have a good rebirth or not a good rebirth, whether the consciousness has left properly or not. Geshe-la came out and he had this big smile on his face. I mean his friend just died! He comes out smiling and he’s chattering in Tibetan saying, “Oh, he died so well. He was in the right position. You could tell he was meditating and he let his consciousness go to the pure land.” He came out, he was so happy.

This made such an impression on me of a practitioner, because this was just an ordinary monk—one of these old monks around Dharamsala who nobody notices. He was just an ordinary practitioner who did really serious practice, and then died so well. His death was so inspiring for those of us who were there. It was so amazing. It made me think, “This is the benefit of meditating on impermanence and death—is that, it makes you practice and when you practice, then you die very, very peacefully.”

How to remember death and why we do so

The question then is, “Well, how do we remember impermanence and death?” Here there are two ways to do it. One way is called the nine-point death meditation and the second meditation is imagining our own death. These are two different meditations. I’ll talk about both of them because this is really valuable for us in our practice. Now I need to preface this by saying that the purpose of thinking about death is not to get morbid and depressed, okay? We can do that all by our self. We don’t need to come to Dharma class to learn how to get morbid and depressed. That’s not the purpose. And the purpose isn’t to get a kind of fear that’s panicky like, “I’m going to die, aahhhh !” We can do that all by ourselves too.

The purpose of thinking about impermanence and death is so that we can prepare for it. We do this so that at the time of death it isn’t frightening. We do it so that at the time of death we’re ready to die and we’re very peaceful. We prepare for death by practicing the Dharma: by transforming our mind; by giving up our ignorance, anger, selfishness, clinging attachment, pride, jealousy; purifying our negative actions; creating positive actions. This is how we prepare for death. This is what this meditation is designed to inspire in us, and it does a really good job. If we meditate well on impermanence and death, I know for myself, my mind gets very calm, very calm, and very peaceful. Can you imagine that meditating on death makes your mind so calm and peaceful?

Again, I remember when I was living in India, one of my teachers was giving us some private teachings in his room. He was going through one text by Aryadeva, Aryadeva’s Four Hundred. That text has a whole chapter about impermanence and death. For like a week or two, every afternoon he’s teaching us impermanence and death. Then every evening I’d go home and I’d meditate on what he’d taught us. Those two weeks, when I was really practicing this meditation intensely, my mind was so peaceful.

My neighbor used to play her radio loud. It used to disturb me. It didn’t disturb me during that time. I wasn’t upset with her for playing her radio loud. I didn’t care because her playing her radio loud was inconsequential in the big scope of things. Somebody said something that was hurtful to me and I didn’t care. This was because in the big scope of things, when you think about life and death and what’s important when you die, somebody criticizing me or offending me? Who cares? It’s no big deal. Or, things not happening the way I want them to happen? Considering I’m going to die this is no big thing. Just thinking about this really helped me put things in perspective. It helped me let go of a lot of things that normally my mind would make a big fuss about. That’s why I say that this meditation can make your mind very calm and peaceful, really focused and centered.

The nine-point death meditation

Let’s look at the nine-point death meditation and how to do it. The nine points are divided into three subgroups. Each subgroup has a heading and under it three points and then a conclusion at the end of that—that’s the format for each of these three subgroups.

- The first subgroup is death is definite.

- The second subgroup is the time of death is indefinite.

- And the third subgroup is at the time of death only Dharma is important.

Let’s go back and look at those three subgroups and look at the three points under each one and the conclusion of each one.

Death is definite

Everybody dies and nothing can prevent death

The first point under that is that everybody dies. This is something that I think we all know already, don’t we? Everybody dies. But we know it up here in our head and we haven’t really actualized that. It’s very helpful just in this first point—that everybody dies and nothing can prevent our death—here what I do at this point is I start thinking about people I know and remembering that they die.

If you want you can start with historical figures. Look, even the great religious leaders all died. The Buddha died, Jesus died, Moses died, Muhammad died. Even great religious leaders die. Nothing prevents death. Also the people we know, our grandparents, our parents maybe have died. If those people haven’t died yet, they will die. It’s very helpful to think about the people that we are very attached to and remember that they’re going to die. Or even visualize them as a corpse—because it’s reality, they are going to die. To remember this helps us to prepare for their deaths.

Along that line let’s remember also that we’re going to die. One day we’re going to be a corpse lying out and people will come and look at us. If we had a regular death, not in an accident, they’ll come and look at us and go, “Too bad”. If they embalm us, “Oh, she looks so peaceful.” Or maybe people will be crying or who knows what they’ll be doing. But one day we’ll be laid out, unless we’re in too bad of an accident and they don’t want to show the body to anybody. Just to think everybody’s going to die whether we know them or don’t know them. Go person by person. Think about that and really let that sink in. That’s very powerful for our mind.

Our lifespan can’t be extended when it’s time to die

The second point after nothing can prevent death and everybody dies is that “Our lifespan can’t be extended when it’s time to die.” Our lifespan is getting shorter moment by moment. When it runs out, there’s nothing you can do. Now it’s true that sometimes people are sick and we may do certain spiritual practices to remove karmic obstacles that may bring on an untimely death. So that can remove an obstacle to somebody living out their whole lifespan. But our bodies aren’t immortal and most of us are not going to live past a hundred—definitely. How old is the oldest known human being? I don’t even know.

Audience: Just a little over a 100, a 110 or something.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Figure 120. Definitely most of us here are over twenty-five, so figure in another 100 years for sure we’ll all be dead. Everybody sitting here in this room won’t be here any longer. This room may still be here but none of us are going to be alive on this planet and other people are going to be using this room. There’s nothing we can do to extend the lifespan past a certain point because the body by its very nature dies: it decays and dies. From the time it’s born, it’s in the process of decaying and dying and there’s nothing we can do that can prevent its demise. There are even stories at the time of the Buddha. Was it Maudgalyayana who was the one who was very skilled in magical powers? I think it was him. Anyway, he could do all these fancy magical powers and go to another universe and things like that, but even if you do that you still can’t avoid death. So even if you have clairvoyant powers, even if you can fly in the sky, even all sorts of special things people can do—it doesn’t prevent death. Every moment that’s passing, we’re getting closer to death. That’s really something to think about.

Every day when we wake up in the morning to think, “I’m a day closer to death than I was yesterday.” The next day, “I’m a day closer to death than I was yesterday.” Geshe Ngawang Dhargye, one of my teachers, used to say that he couldn’t figure out why we Westerners celebrated birthdays. He said, “You’re only celebrating that you’re one year closer to death. What’s the point?” It’s true when we think about it. The lifespan is running out. If we think of our lifespan like an hourglass and the sand’s going down there, there’s only so much sand in the upper part of the hourglass. One day it’s going to run out. There’s no way you can stop it from going down. That’s just the nature of things, so there’s no way to extend our life span.

Death is definite even if we haven’t had the time to practice the Dharma

Then the third point under death is definite is that it’s definite to happen even if we haven’t had the time to practice the Dharma. Sometimes in our mind we think, “Well, I won’t die until after I’ve practiced the Dharma. Since I’m too busy today, I’ll do it later. So, I’ll die later.” But that’s not true. They tell the story in the scriptures of a person lived to be about sixty. On his deathbed he looked back and he said, “The first twenty years of my life I was too busy playing and getting an education to practice; so those twenty years were wasted. The second twenty years of my life I was too busy having a career and a family; so no Dharma practice got done then. That was wasted. The third twenty years of my life, my faculties were declining and my body was in pain and I couldn’t remember things so well. So that time got wasted. And now I’m dying.”

It’s true. We die whether we’ve practiced or not. Again it’s helpful to think of our own life specifically. We’re going to die and what are we going to have to take with us when we die? Have we practiced? Are we ready to die?

The time of death is indefinite

This actually leads into the second subheading which is the time of death is indefinite. We might get to the point where we say, Okay, I’m going to die, I accept that death is definite, but we think, I’m not going to die today. I’m going to die later. Even one time I was giving a teaching like this and I came to this point about the time of death is indefinite. One man raised his hand and said, “Well, the insurance company says that the average length of women for life is da, da, da, and for men is da, da, da, so we have another few years left.” And I said, “Oh?” So we always have this feeling: death isn’t going to happen today. Even the people who die today, what is it? May 23, 2002. Even the people who die today, when they woke up this morning did not have that thought, “Today I could die.” Let’s say people in the hospital—people who woke up in the hospital this morning, some of them are going to be dead by the end of the day. Aren’t they? They have terminal illnesses in the hospital or in old-age homes. I don’t know if any of them thought, “Today could be the day I die.” They probably think, “I’m sick. It’s terminal but I’m not going to die today. I’ll die later. Even though it’s terminal, I still have some time. I’m not going to die today.”

How many people die in accidents? Those people who are terminally ill, they don’t think, “I’m going to die today.” How many people are healthy and then die in accidents? They also didn’t think, “I’m going to die today.” Here I’m sure we all have stories to tell of experiences about people we know who have died very suddenly without any warning at all. When I was first learning this one of my friends told me the story about her sister. Her sister was in her mid-twenties and she loved belly dancing. This was several years ago before they had CDs so her sister would practice belly dancing to a record.

One evening her sister and her husband were at home. Her husband was in one room reading and her sister was practicing her belly dancing with a record. Then the husband, all of a sudden, heard the record just get to the end and keep scratching—you know how the record just keeps scratching at the end? He didn’t understand what the matter was because his wife always would play it again and keep practicing. He went in there and she was dead on the floor—a woman in her mid-twenties. I don’t know what it was, if it was a heart attack, or an aneurysm, a brain aneurysm, or what it was. I don’t remember now. But just like that, someone who was totally healthy.

People dying in car accidents: they get up in the morning, “Oh, I have so many things to do today. I have to go so many places.” Get in the car and don’t even make it a mile from their own house and they’re dead. Look at 9/11, isn’t 9/11 the perfect example of the time of death is indefinite? And the interviews they did with people after that, people telling about their lives, and all their hopes for their families, and what they were going to do. It was a normal regular workday but they didn’t make it past ten o’clock. They were all dead by then.

So for us to have this feeling that we’re going to live forever or even the feeling that we’re not going to die today, it’s totally unrealistic. It’s totally beyond the bounds of realistic thinking, isn’t it? Now we can say, “Well, look how many days of life I’ve had so far and I haven’t died yet, so isn’t it correct to assume that today also I won’t die?” But the time of death is indefinite. Death is definite. Definitely one day is going to come when we’re not going to get past that day. We need to really be mindful of that: every day this day could be the day we die. Ask ourselves, “Am I ready to transition into my next life today? If death all of a sudden happens today, am I ready to let go? Do I have things that are left undone, things left unsaid, that need to really be taken care of before I die?” And if we do, to be on top of our lives and do those things in case today is the day that we die.

There’s no certainty of lifespan in our world

The first point under this one, that the time of death is uncertain, is that, in general, there’s no certainty of lifespan in our world and that people die in the middle of doing all sorts of different things. So there is no certainty of lifespan. Some people might live to be 100, some people until 70, some to 43, some to 37, some to 25. People die in their teens. People die as children. People die even before they get out of the womb. There’s absolutely no guarantee about how long our lifespan is going to be because we die at all sorts of different times.

We’re always in the middle of doing something when we die

Also we’re always in the middle of doing something when we die. We might have this kind of notion that, “Okay, death is definite but I’ll organize my life and take care of everything I have to take care of and when everything is taken care of, then I’ll die.” We always like to organize everything and plan it out. But there’s no fixed lifespan and we’re always going to be in the middle of doing something.

When have we ever finished all of our worldly work? Even the rare days when you clear off all your email, your inbox, five minutes later there’s more email. There’s no end to it. No matter what work we’re doing, there’s always more worldly work to do. If you work in a business, there’s always another day of manufacturing things, or another day of serving your clients, or another day of fixing things. We never get all of these things done. If we have the mind that says, “I will practice Dharma later when all my worldly work is accomplished,” we’re never going to get to that point where we have time to practice the Dharma. There’s always going to be more stuff to do.

This is one of the crux, the key points, that people don’t see—why they don’t have time for Dharma practice. It’s because they keep thinking, “I’ll finish all these worldly things first, then I’ll practice the Dharma because then I’ll have more time.” You never get to that point where it’s all taken care of. There’s always something more. People are always in the middle of something. People go out to dinner, they have a heart attack in the middle of eating dinner and they die. I’ve certainly heard stories about that happening to people.

I heard a story in China that there were some people who got married. In China you always put off the firecrackers as celebration. This young couple, they were crossing under a doorway, they put off the firecrackers. The firecrackers fell down on them and killed them as they were going off. On your wedding day you get killed. In the wedding celebration you get killed. It’s amazing, isn’t it? We’re always in the middle of doing something, going somewhere, finishing a project, in the middle of a conversation. Even you’re lying in the hospital bed, you’re in the middle of one breath and you die. You’re in the middle of a sentence, you’re in the middle of a visit with a relative and you die. Accidents, you’re in the middle of a conversation. So the time of death is indefinite. It happens at all different sorts of times.

There are more chances of dying and less of remaining alive

The second point under that is that there are more opportunities of dying and less of remaining alive. In other words, our body is very fragile and it’s very easy to die. If you think about it, it’s true. We think, “Oh, my body’s so strong.” This kind of macho feeling, “I have such a strong body.” Then you get one tiny virus that you can’t even see with the eyes and it kills you, one tiny virus. One tiny little piece of metal goes in the wrong place in our body, like that we’re dead. One teeny, teeny blood clot gets lodged in the brain or gets lodged in an artery of the heart, we’re gone. We think that our body’s so strong; but our skin gets cut so easily, just a little piece of paper cuts our skin. Our bones break very easily. All of our organs are very fragile, they are easily damaged. It’s very easy to die. Our body is not that strong.

Our body is very fragile

That leads into the third point which is: our body is extremely fragile. So second one is there are more chances of dying and less of remaining alive; and third is that our body is very fragile. It’s true, it is.

If we look, why does it say that there are more chances of dying and less of remaining alive? Well, we have to exert so much effort to stay alive; to die takes absolutely no effort. To die, all we have to do is lie down, not drink, not eat, we’ll die. Not take care of our body, we’ll die. It requires absolutely no effort for our body to die. To stay alive, we have to grow food, we have to cook food, we have to eat food, we have to get clothes to protect our body. We have to get medicine to keep the body healthy. We have to build houses to take care of the body. We spend so much time and energy in our life taking care of this body. Why? It’s because if we didn’t the body by itself automatically would die. Think about it a little bit—how much time and energy we have to put into taking care of our body and keeping it alive. So it is very easy to die and our body is fragile.

Let’s review here. Under the first point that death is definite we said that nothing can prevent us from dying, that everybody dies. Second is that our life span won’t be extended at the time of death and that it is ending moment by moment. And third is that we can die without practicing Dharma. The conclusion from those first three points under death is definite, the conclusion we draw from contemplating that is that: I must practice the Dharma.

Audience: What is Dharma?

VTC: Dharma means the Buddha’s teachings, the path to enlightenment. Practice Dharma means transform our mind: let go of the selfishness, the anger, the ignorance, these kinds of things; develop our inner qualities.

Then the second main heading, that the time of death is indefinite. The three points under that are first, that we’re always going to be in the middle of doing something when we die, that there is no certainty of life span. Second, that there is more opportunity to die than to stay alive because we have to exert so much effort to stay alive. And third that our body is very fragile, even small viruses and pieces of things: you eat the wrong food and you can be dead. So our body is very fragile.

Conclusions

The conclusion from thinking about those three points is that I must practice Dharma now. The first conclusion was that I must practice the Dharma. The second is that I must Practice the Dharma now. Why now? It’s because the time of death is indefinite and I could die very soon and I can’t afford to have this mañana mentality because I may not live that long.

Nothing can help us at the time of death except the Dharma

Our money and wealth are of no help at the time we die

Now we get into the third subheading which is nothing can help us at the time of death except the Dharma. That’s the third broad heading. The first point under that is that our money and wealth is of no help at the time we die. It doesn’t matter if you’re rich or you are poor, when you die, you die. It doesn’t matter if you are lying in a gutter or in an expensive bed with golden sheets, none of our wealth can prevent us from dying.

I had real interesting situation that I was called into—Bill Gates’ best friend was dying. He was somebody at Microsoft who Gates was very close to and he had lymphoma. Gates loaned John his jet to fly him all over the country to go to specialists. He went to the best doctors. Money wasn’t an issue because Microsoft was doing very well. He had the jet to fly and all the wealth: couldn’t prevent death, didn’t do anything to prevent death. At the time of death none of the wealth was important. This man was actually very smart and he understood that. In spite of his wealth he understood that the wealth wasn’t important. I was quite impressed with the way he died.

If wealth isn’t important at the time we die, why do we spend our whole life worrying about it, and working so hard to get it, and being so stingy and not wanting to share it? At the time we die all of our money and wealth stays here. It doesn’t go on to our next life with us. Yet look how much negative karma we create trying to get it and protect it. Is it worth it? And how much worry and anxiety we have over that?

Audience: So if you practice the Buddha’s teaching, this means you don’t have to be afraid of dying? Is that what it means?

VTC: Yes, that’s what it means. It would be nice to not to be afraid of dying, wouldn’t it?

Audience: What else?

VTC: Well, I’m getting there.

Audience: I don’t understand this part.

VTC: Our wealth is of no importance when we die. So why do we worry and fret about it so much when we’re alive? Especially since it all stays here and we die. Then our relatives all quarrel over who gets it. Isn’t it a tragedy when relatives or siblings quarrel over their parents’ belongings and wealth? I think that’s so sad. The parents worked so hard to get it and then all that happens is that their children, who they love, create negative karma fighting over it. Tragedy.

Our friends and relatives aren’t of any help to us at the time we die

Second is that our friends and relatives aren’t of any help to us at the time we die either. They can all be gathered around us, but none of them can prevent us from dying. We can have our spiritual teacher there, we can have all of our spiritual friends there, we can have everybody praying for us, but that can’t prevent us from dying. At the time we die it’s said that they don’t help us in the sense they can’t prevent us from dying. Also they can’t necessarily make our mind into a positive state when we die. We have to make our mind into a positive state. They might be able to help. They remind us of the path, remind us of the teachings, give us some advice, do some chanting that reminds us. But we are the ones that have to put our mind into a good mental state when we die. Nobody else can do that. When we die our friends and relatives stay here and we go on alone—none of them accompany us into death and help us out. It’s an adventure. It’s a solo adventure, solo flight.

Given that, what’s the use of being so attached to other people? This is a real important question. Given that our friends and relatives can’t purify our negative karma, can’t come with us when we die, and can’t prevent our death—why are we so attached to them? What’s the use of being attached? What’s the use of the mind that wants to be liked and popular and loved? None of that can prevent us from dying. None of that can make us have a good rebirth. None of that can get us closer to enlightenment. This way of thinking, this meditation, hits on some of our real core attachments and really makes us call those things into question.

At the time of death even our body is of absolutely no help

The third point under this is that at the time of death even our body is of absolutely no help. In fact our body is the thing that betrays us when we die. This body that we’ve been with since day one, that’s always come around with us. At the time we die it stays here and our mind, our consciousness goes off into another life. Given that our body stays here, what use is it worrying so much about how we look? We’re always worrying about how we look and, “Does my hair look nice, my makeup? Am I showing my figure off?” The guys are worrying about, Are my muscles strong, am I athletic, are all the women going to be attracted to me?” Or, we are always worried about our body and keeping it well, keeping it attractive. Yet our body just totally betrays us when we die. It stays here and we go on.

Even if they embalm us and we look so beautiful when we are dead, so what? If you have clairvoyant powers from your future life, do you want to look back at your previous corpse? Are you going to get any status out of, “Oh, my previous corpse was so beautiful. Everybody is praising how nice I looked, how nice my corpse looked.” My friend’s mom was dying of cancer, she eventually died. She looked horrible when she was dying. After she died, they embalmed her and at the funeral people were saying, “Oh, she looked so beautiful now.” Who cares?

Also who cares about our prestige during our life and our power during our life? When we die all that prestige and power and fame is gone. You look, this century some of the most powerful people: in our case Stalin, Hitler, Truman, Roosevelt, Mao Tse Tung, Li Quan Yu—whoever it is. All these very powerful people, what happens after they die? Can their power do anything after they die? They may be very powerful and famous, maybe like Marilyn Monroe while you are alive, be very famous and have everybody ogle over you. When you die none of that comes with you, it’s all just past tense. So what use is it worrying so much about if we are famous, if other people appreciate us, if we’ve attained the status and the rank that we aspire for?

Even if we attain whatever status and rank, we might not aspire to be politicians or movie stars. But in our own little lives we have our own little things that we’re attached to and things we want to be famous for. You want to be the best golfer in Jefferson County—whatever it is. We get attached to all these things. What use is that if when we die, none of it comes with? And our picture may stay behind, “Oh, there: Prom Queen, golf champion, or the best person who grows the nicest Bonsai trees,” whatever your thing is. There might be pictures of you and you might even be in the wax museum or Hall of Fame. When we leave this life, who cares? We’re not even going to be around to appreciate it. If none of it is important in the long haul, why do we worry about it so much while we are alive? Why get so obsessed and so worried and so paranoid and so depressed and all this kind of stuff? It’s not worth it.

We need to practice purely

We conclude from meditating on this is that we need to practice purely. So we not only need to practice the Dharma, we not only need to practice it now, but we need to practice it purely. In other words, we need to work to transform our mind—to really make our mind happy through spiritual practice. That’s the real kind of happiness.

We need to practice the methods to do that in a very pure way without looking for any kind of ego boost along the way. This is especially said because it’s so easy when we are practicing a spiritual path to look for ego perks. I want to be known as a good Dharma teacher. I want to be known as a fantastic meditator. I want to be known as a scholar. I want to be known as somebody who’s very devout. If I have a good reputation as a good spiritual practitioner people will support me, and they’ll give me offerings, and they’ll honor and respect me, and I’ll get to walk in the front of the line, and they’ll write newspaper articles about me.

This kind of thought very easily can come into our mind when we’re trying to do a spiritual path but that pollutes our motivation. Practicing the Dharma purely means to go ahead with our spiritual practice without looking for these ego perks along the way. And just to really try and overcome our self-centeredness and develop impartial love and compassion. Try and see through the ignorance that covers our mind and see the emptiness of the self and phenomena. That’s what we need to do—to really practice this in a pure way as much as we can. So you see, when we meditate on death then the motivation for spiritual practice comes from inside. Then we don’t need people to discipline us to practice.

Often in a monastery we have to have a daily schedule of what time to meditate, what time to chant, and do these things. This is because we sometimes we lack our own internal discipline. When we have an understanding of death and impermanence we are self-disciplined. We have our own internal discipline because our priorities are real clear. We know what is important in life, we know what’s not important in life. Nobody needs to tell us, “Go and meditate.” Nobody needs to tell us to go do our purification and to confess when we made mistakes. Nobody needs to tell us to make offerings and create good karma. Nobody needs to tell us to be kind. We have our own internal motivation because we’ve meditated on impermanence and death.

Then spiritual practice becomes so easy. It becomes a breeze. You wake up in the morning and it’s like, “I’m alive. I’m so glad for being alive. Even if I die today (because the time of death is indefinite), even if I die today however long I have to live today, I’m so happy for it. I appreciate it because I can really practice and make my life highly meaningful.” Even through very simple actions in our life that we do with a positive motivation we give our life meaning.

So this is the value of doing this meditation on impermanence and death—it’s so incredibly important. It gives us so much positive energy. For me this meditation is one of the best things to do to remove stress. Doesn’t that seem funny that you meditate on death to relieve stress? But when you think about it, it makes perfect sense. Because what do we get stressed about? “I get stressed because I don’t have enough money to buy the thing I want because I over extended my credit card.” “I get stressed because I have so many things to do and everybody is breathing down my back to get them done.” “I get stressed because I did my best on a job and somebody criticized me and didn’t appreciate what I did.” When we think about these kinds of things in light of what’s important at the time we die, none of these things are important! We let go of them. Then there’s no stress in the mind. It’s incredible how peaceful the mind gets when we think about death and really set our priorities. Best stress reliever, isn’t it? It’s fantastic. That’s why we need to really put some effort into this meditation.

How to meditate on death

When we do this meditation, the way to do it is to have this outline with the three major points, the three sub points under each one and the conclusion on each of the major points. You go through and you think about each point. Make examples in your own mind. Relate it to your own life. Think about that point in relationship to your own life. Make sure that you come to those three main conclusions after each point. Come to those and really let your mind stay as single-pointedly as you can on those conclusions. Let that really sink into your heart. It has a tremendous transformative affect.

I talked quite long this time. Do you have any questions?

Audience: I was thinking that if somebody did know when their death was going to happen—let’s say they were given six months to live or something. Would you do things differently? I was told there was a book called One Year to Live where you’re really supposed to imagine that you are going to die. I’m sure all of this would be helpful. But would you really stop your daily activities and just focus on this completely?

VTC: Okay, if you knew what your time of death would be, would you alter your life? First of all, none of us really know when our time of death is going to be. Even the doctors say, “You have six months.” The doctors are guessing. They have absolutely no idea. You could have six days or six years.

But the point is this: when we do this meditation we may see that some things we do in our life we really want to stop. We see they’re not worthwhile. Then there are other things that we need to do to keep our body alive and to keep our life going so we can practice. So we do these. When we have an awareness of impermanence and death, we do them with the motivation of bodhicitta instead of with a motivation of our own selfish pleasure. We still need to eat to keep our body alive. Understanding that we’re going to die doesn’t mean we don’t take care of our body. We do take care of our body. We still need to eat. But now instead of eating because I want to eat because it tastes so good, and it will make me look beautiful and strong, and all this stuff? We eat instead like the verse that we chanted before we ate lunch today. We do it to sustain our body in order to support the brahmacharya.

The brahmacharya means the pure life—the life of practicing the Dharma. We eat but with a different motivation. Instead of one of attachment, we do it a motivation to sustain the body so that we can practice for the benefit of our self and others. You still clean your house. You can still go to work. But the motivation for doing all these things becomes different. And then some things we decide just to leave behind altogether because they are not important to us.

Audience: Now what about? It’s like last night when I was driving, some people drive crazy. So I get scared. I get fearful that they’ll cut me off. I worry that I’ll get in an accident and die. Whenever I encounter instances like that, or experience fear at all, I always try to relate it back to self-grasping—so that I keep it all straight in my mind. So how do you then … it’s said that biological organisms, it’s hard wired into you to perpetuate your life. If you realize emptiness would you never have any fear of dying? So you are able to somehow transcend the biological urge? Or is what is called the biological urge simply the self-grasping that has been burned into our mind streams?

VTC: The biological urge, I think a lot of that has to do with the self-grasping—that we’re so attached to our body and we don’t want to let go of “my body.” I think that’s one of the things. Also this whole image, it’s attachment to the body and it’s also ego identification. This is me and I don’t want to give up being me! Who am I going to be if I’m not me? And if I don’t have this body, then really who am I going to be? So I think a lot of that is ego grasping.

Audience: It occurred to me last time when I was driving. My heart was calming down after some crazy person nearly ran me off the road. I started wondering, “Well how much is this ignorance and how much is simply that I wound up with this?”

VTC: It’s hard to say. Maybe some of that is a biological thing; but that the mind doesn’t get afraid—that might happen also. I’m trying to think if an arhat was being threatened by somebody … I don’t know. We’d have to ask an arhat. Maybe the body still has a reaction of adrenaline so he can escape, but the mind itself isn’t fearful.

Audience:How can you help yourself not to be afraid of dying?

VTC: Okay, so how can you help yourself not be afraid of dying? I think as much as possible during our life to live with a kind heart and to not harm others. In that way we create a lot of positive karma and we abandon negative karma. Then at the time we die, if we take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, if we generate our kind heart in a wish for compassion, then that makes our mind very peaceful at the time we die. If we can have a peaceful mind when we die, because we are thinking of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, or because we have love in our heart, or because our mind—we generate the wisdom understanding emptiness. If we can have that kind of mind when we’re dying, then it becomes much easier just to let go. And when we’re not grasping onto the life, then there’s no fear. Then we die and it’s just very peaceful. It can even be happy.

Let’s sit quietly for a couple of minutes to do a little meditation.

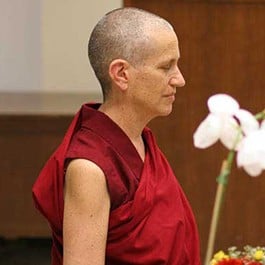

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.