The seven jewels of the aryas: Ethical conduct

Part of a series of short talks on the Seven Jewels of the Aryas.

- The importance of ethical conduct

- How hurting others hurts us too

To continue with the seven jewels of the aryas. The first one was faith, which we talked about before.

And to tell you (the people online) the resolution to the talk I gave two days ago about the turkeys fighting and our concern with them killing each other. Later on that afternoon, I looked out my door and the three of them were happily pecking in front to find food. Two of them were kind of beat up, but at least they were alive, and they were friends again. Don’t ask me why they fought, don’t ask me how they made up, but they certainly created a lot of negative karma and caused themselves and the other ones a lot of misery in the process of their quarrel.

This actually relates to the second jewel of the aryas, which is ethical conduct. And the basis of ethical conduct is not harming. The turkeys would have been wise to remember that.

What is so interesting when we really look at our experience is that whenever we harm others, we are harming ourselves. We usually think, “Oh, somebody’s harming me, so I will harm them back. And when I harm them back then my harm stops.” But actually, because of the way the law of karma and its effects operates, when we retaliate, or even if we’re the ones who start it…but we’re never the ones who start it, it’s always somebody else, isn’t it? We never start the argument. My brother was always the one who started it, and I always got blamed for starting it, because I was older. It’s unfair. But that’s exactly how we think, isn’t it?

When we harm somebody else, it’s clear the harm that they receive. How do we harm ourselves in the process? It happens in two ways. One is we don’t always feel so good about ourselves later on. And I think a lot of our emotional difficulties, or internal turmoil, comes because of ways we’ve harmed other people in the past, and we don’t feel good about ourselves for doing it, but it’s hard to acknowledge and really open up and confess it, and regret it, and determine not to do it again. So we rationalize, justify, and all that kind of stuff, and meanwhile the stuff stagnates inside like rotten junk, and it just grows moldy, psychologically, inside of ourselves, and I think that’s one reason that can cause a lot of psychological disquietude later on. That’s one way we harm ourselves.

The other one is very clearly we create destructive karma. So we put the seeds of that karma on our mindstream, and then it ripens later into suffering experiences that we under go; either by being born in an unfortunate rebirth, encountering problematic situations once we’re born human, having the habit of behaving poorly, being born in a very treacherous or difficult environment. All these kinds of things come about to ourselves in the future, that’s the karmic result of harming others.

When we have this mind that it’s either me or the other, and it’s either my happiness or their happiness, or it’s either I get harmed or they get harmed, and so we always choose my happiness and their harm over my harm and their happiness. But actually, when you look at it, when we harm others, we harm ourselves. When we harm ourselves, we’re harming others. When we harm ourselves, then it creates a lot of problems for a lot of people around us. We’re not isolated individuals. When we benefit ourselves, it benefits others, if we benefit ourselves in a Dharma way, by really taking care of ourselves, taking care of our mind. And when we benefit others, then we also benefit ourselves, because we create merit, we create a happy environment in which we can live.

We shouldn’t think so much in these terms of us and them because we’re very much intertwined.

The point is that our actions affect ourselves and our actions affect other people.

This is one thing in my work with inmates that they bring up a lot when we’re corresponding. I ask them, “How did you land in prison and what’s going on?” Many people don’t ask the incarcerated people what they did. But I’m quite straightforward and I ask them. Also, if they’re writing to me and they want to be helped, then I need the background of what happened so that I can help them. But it comes up again and again of people saying, “I didn’t realize the long-term effects of my actions. I didn’t even realize the short-term effects of my actions. I was completely overwhelmed by afflictions.” And then, of course, you’re overwhelmed by afflictions, and you haven’t developed a habit of, prior to getting overwhelmed by afflictions, of really thinking about what are the results of my actions.

We shouldn’t think, “Oh, this is the problem of people who are ‘criminals.'” Because criminals are ordinary people like the rest of us. It isn’t that they’re a whole different class of people. They’re exactly like the rest of us, except, in some occasions, they happen to get caught for doing things that the rest of us don’t get caught for doing. It could be being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It could be because of discrimination on the part of the (in)justice system or the law enforcement system. We shouldn’t make that divide of us and them, and we’re not like them, and they’re not like us.

I remember one of the guys I wrote to for a long time–he got out and we met a couple of times after he got out. We’re not in touch now. But he had gotten quite wealthy through being a big drug dealer in Southern California and was going to do one last big deal and then go live in Australia or New Zealand or Canada or somewhere else, because he had plenty of money by then. But he got busted at that one, and they gave him a twenty-year sentence. He was in his early 30s at that time, I think. That was just devastating for him. While he was in prison he really thought about what he did, and he wrote me a letter that talked about…because he was tracing back: here’s the situation where I got busted. How did I do that, what was I thinking. That came from this situation and thinking in this way, and that happened from this situation…. And he was tracing things back to even decisions he made when he was a kid. And he was saying these–he called them SIDS–seemingly insignificant decisions. Some started when he was a kid, that led to a situation, that led to another, and so on. So these seemingly insignificant decisions led him to where he was. So of course he had very deep regret about it. But that was really what enabled him to change, was when he began to see the results of his own actions and own those.

Another thing that happened to him is while he was incarcerated (or maybe it was before he went to prison, I don’t know), but he had put some of his belongings in the name of some of his friends so that the police wouldn’t take them. Once he was in prison, his friends sold the stuff and kept the money. So he was betrayed by the very people that he trusted. And he was very angry about that. That made him really, really upset. But then I think it also caused him to think, “What did I do that I made friends with those people who would act like that? What was I thinking that I chose those friends? What was I doing that those were the people I met and started hanging out with?” Again, this reflection on his own behavior and how his own behavior affected him, but also how it affected so many other people. Because he also began to see that becoming the big drug dealer that he was, he harmed many other people’s lives. This was before the whole opioid thing. I think he was in the crack (cocaine) era. Maybe even before that.

This was when he really kind of woke up and began to see, “Oh, I create the cause of my happiness and my suffering.” And I think that’s the basic understanding that we need to have in order to keep ethical conduct. Keeping ethical conduct, taking and keeping precepts, is because we understand, “My actions have an effect. They aren’t just little things in the sky that disperse. They have an effect on me, on other people, in this life, in future lives.” And if you have that understanding, then ethical conduct (I think) comes very natural to you. And keeping precepts is not a big deal. Because that’s what you want to do anyway. So if you see your precepts as, “I can’t do this and I can’t do that, and all these can’t dos, and I’m suffering and it’s oppressive.” If you see precepts like that, then you haven’t really understood the working of the mind and how we cause our own happiness and suffering, and how our actions affect ourselves and others. I think that’s something that we really need to go back and look at in a deep way, and then it becomes so much easier to practice ethical conduct.

Of course, sometimes our afflictions come on strongly, and we get angry, and the words are coming out of our mouth before we’re even aware of what’s going on. That happens. Or we get really afflicted and we plan out a whole series of lies, again without realizing the effect that those lies are going to have on us, on the people around us, now, in the future. We do get overpowered by afflictions. But I think the more we really think about the effects of our actions then the easier it becomes to restrain, and to grow our mindfulness, to grow our introspective awareness, so that we can refrain from harmful actions.

Audience: I just want to agree with what you said about harmful actions having a psychological effect down the line. I was just doing purification in the meditation hall and I saw that I have this compulsive way of thinking, and I didn’t know where it’s coming from, but I was able to see that there’s a lot of self-hatred underneath that. That comes from past misdeeds. But that was completely buried, I couldn’t see those connections. The purification practice is so important for uncovering why we do certain things and how we feel about ourselves. Because I’ve been living in denial thinking, “Oh I’m pretty okay with myself.” But there are some areas that are where I’m really regretful and really ashamed.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): That’s the power of purification.

Audience: I was thinking that another way that harming others harms us is the situations it creates in the moment. It creates bad relations with others and conditions for negative things from our past to ripen. If we harm someone, they might want to harm us. It’s kind of the opposite where you were saying when we help others, it creates nice situations. It’s kind of the opposite of that.

VTC: Very true. We create a situation around us when we harm, when we benefit, and that situation can influence the ripening of either virtuous karma or non-virtuous karma, depending upon the situation we create around us.

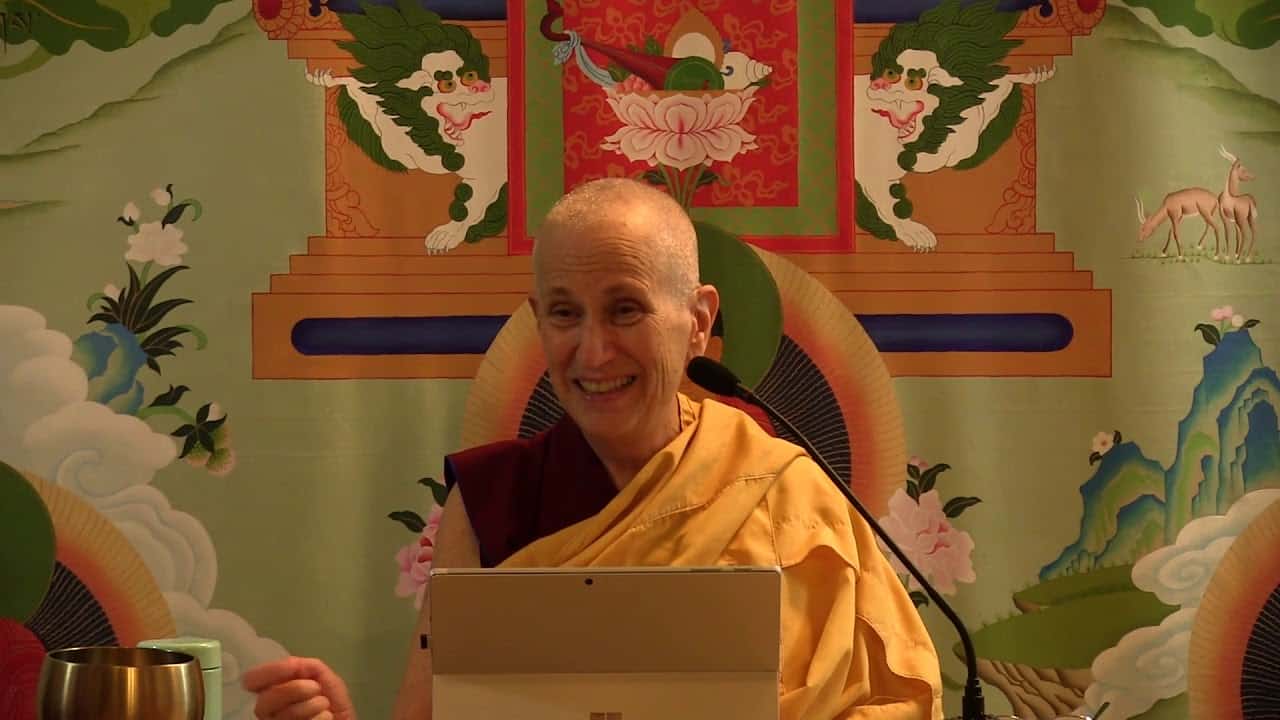

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.