The seven jewels of the aryas: Faith

Part of a series of short talks on the Seven Jewels of the Aryas.

- The first jewel of the aryas

- Three kinds of faith: appreciative, aspiring, and faith that comes from conviction

Friends of Sravasti Abbey Russia asked me to do a series of talks on the seven jewels of the aryas, because they want to (as I understand it) make a little book using those seven jewels as the framework. And then selecting some of the stories from the website that have been written by incarcerated people as examples of those seven jewels. And then to make a little booklet, which I think is a great idea.

The seven jewels are mentioned in several different texts. Nagarjuna mentioned them in his Letter to a Friend, verse 32. They read:

Faith and ethical discipline

Learning, generosity,

an untainted sense of integrity,

and consideration for others,

and wisdom,

are the seven jewels spoken of by the Buddha.

Know that other worldly riches have no meaning (or no value.)

Atisha also spoke of this in his Bodhisattva’s Jewel Garland, verse 25, which is almost identical. It mentions the seven, just the wording is a little different.

The first one is faith. You’ll remember when we studied Precious Garland, that Nagarjuna, when he talked about the two purposes—the higher rebirth and highest good—and he said that faith is what promotes the higher rebirth, because we need faith in order to live by the law of karma and effects. But for the highest good, meaning liberation and full awakening, that requires wisdom. But he said faith is actually the one that comes first, even though it’s the one that often is more difficult to have. Because the wisdom of emptiness is a slightly obscure phenomena that we can understand by factual inference. But to have faith, we often need the inference by the power of belief. That inference is a bit difficult to get, but we can certainly go in steps towards it.

There are three different kinds of faith, and not all of the require that kind of inference.

The first kind of faith they talk about in mind and mental factors is appreciative faith. Faith that sees the good qualities of, for example, the buddhas and bodhisattvas, and appreciates and respects them. When you study about refuge, when you learn the qualities of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and you see how amazing they are, then this kind of faith–if you trust what it says about those qualities–then you have that kind of appreciative faith.

The second kind of faith is aspiring faith. This is faith that not only appreciates and respects those good qualities, but aspires to generate them ourselves. We think about, let’s say, the compassion of the Buddha. How the Buddha doesn’t judge us and condemn us, and so on. We appreciate that. But then we take it a step further and we say, “I want to be like that, too. I’m sick of my judgmental, critical mind that just likes to pick faults. I aspire to have that mind that can see others’ good qualities, and appreciates and respects them. So, aspiring faith is the second kind.

Then the third kind is faith that comes from conviction, and this faith comes because we’ve studied and we’ve thought about the teachings. They make sense to us. We believe them because of knowing them and thinking about them.

You can see, with all these three kinds of faith, none of them are faith without investigation. In fact, in Buddhism, unquestioning faith is contraindicated, because this kind of faith is not very stable. It may give you a high and a good feeling, but then somebody else comes along and tells you something different, and then what you had faith in disappears, and then you have faith in something else.

You see that sometimes with people. It’s very strong emotional faith, and then a few weeks later they’re following another path. It’s really kind of puzzling, you don’t know how they got from A to B. It’s usually because the faith is not well thought out.

Even using the word “faith” to describe this mental factor is a little bit tricky, because what we think of as the meaning of the English word “faith” is not exactly what the Tibetan word “day-pa” means. It could mean faith in that sense, but it also means trust and confidence. We have trust and confidence in the Three Jewels. It’s not faith without investigation, but it’s a kind of trust and confidence that allows us to settle on the path and to practice the path.

Faith is certainly a remedy to doubt. Doubt is always going, “Well, do I this, do I do that? Do I believe this, do I believe that? I don’t know what to practice. My friends say this is good, and other friends say that is good. They tell me all these qualities of the Buddha, and I don’t even know if they’re true. Because somebody else tells me the qualities of God, and that sounds pretty good too….” You get into this state of doubt, and you’re at the crossroads with a two- pointed needle and you can’t go anywhere.

Faith, when it’s based on at least some knowledge of what you’re having faith in, and thought and appreciation about those qualities, and aspiring to want to generate them and coming from some conviction because you know what you’re having faith in, then that settles the mind down and allows you really to practice and to go into depth in your practice.

That kind of faith also brings a certain kind of stability to the mind. It makes the mind joyful and peaceful, because it’s like, “Oh, I know the direction to go in. I know it. It makes sense to me. I want to go in that direction. And there are reliable guides with good qualities who will lead me in that direction.” We have trust. We have confidence. We have faith in that way.

That’s the first of the seven jewels. And you can see why it comes first. It’s necessary to get grounded so we know what we’re doing.

Audience: In my practice I’ve noticed having to convince myself of certain topics at deeper and deeper levels. So the faith, I think it has many different levels. It’s been very surprising to me to see, oh my gosh, maybe I really don’t believe that, I only have a correct assumption, but it’s not an inference. So you have to convince yourself.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes. And we can’t expect to have inferences or direct perceivers at the beginning. So just try and get a correct assumption.

And as we were saying, there are many different levels of correct assumption.Correct assumption is a step up from doubt. The more you study, and the more you think about what you study, then your correct assumption gets much more deeply rooted.

It is something we need to work on.

“Convincing ourselves.” It depends what we mean by convincing ourselves. If it’s, “I’ve got to believe this, I should believe this, okay I’m going to make myself believe it….” No. That’s not going to work. That’s not going to be helpful.

But if what we mean by it is, “I’m going to think about it, keep it on the radar, keep checking it out, and be open-minded towards that,” then yes, by all means.

Audience: It’s like I have competing beliefs. I mean, I know which one is right, the one that’s in line with the Dharma, but the other way of thinking is just so strong it completely derails. So that’s what I mean by “convincing myself.”

VTC: I see, okay. What I found very helpful for that, and I did this a lot…there was a point where I came home to visit my family before I got ordained. My knowledge of Dharma was still fairly weak. And the view of the family, the ordinary view, was coming at me from all directions. So what I did every evening was I would sit down and think about something that we had talked about or discussed that day, and I would say, “Okay, here’s the conventional view of it from my family and society, and here’s the Buddha’s take on that same subject. If I follow the view of family and society, where does that get me? What is it based on, how does it have me think and act, where does it get me? If I look at the view the Buddha has on that, what is that based on? And if I follow that, where does it get me? This kind of meditation every evening comparing the two views in a really open-minded way, really exploring where each of them leads me, it was very, very helpful in sorting out what I believed and really strengthening my faith in the Dharma. I would take the remarks that my family made, and instead of just (tossing them out), I would think about them, and then I would compare them with what the Buddha said, and let the family and the Buddha have a little dialogue there. And the Buddha really made much more sense.

What I’m getting at is it’s very important to do that kind of thinking, and not just say, “Oh, that’s worldly, push it away.” We really have to see how those views are not based on anything substantial, and how they don’t lead to anything useful.

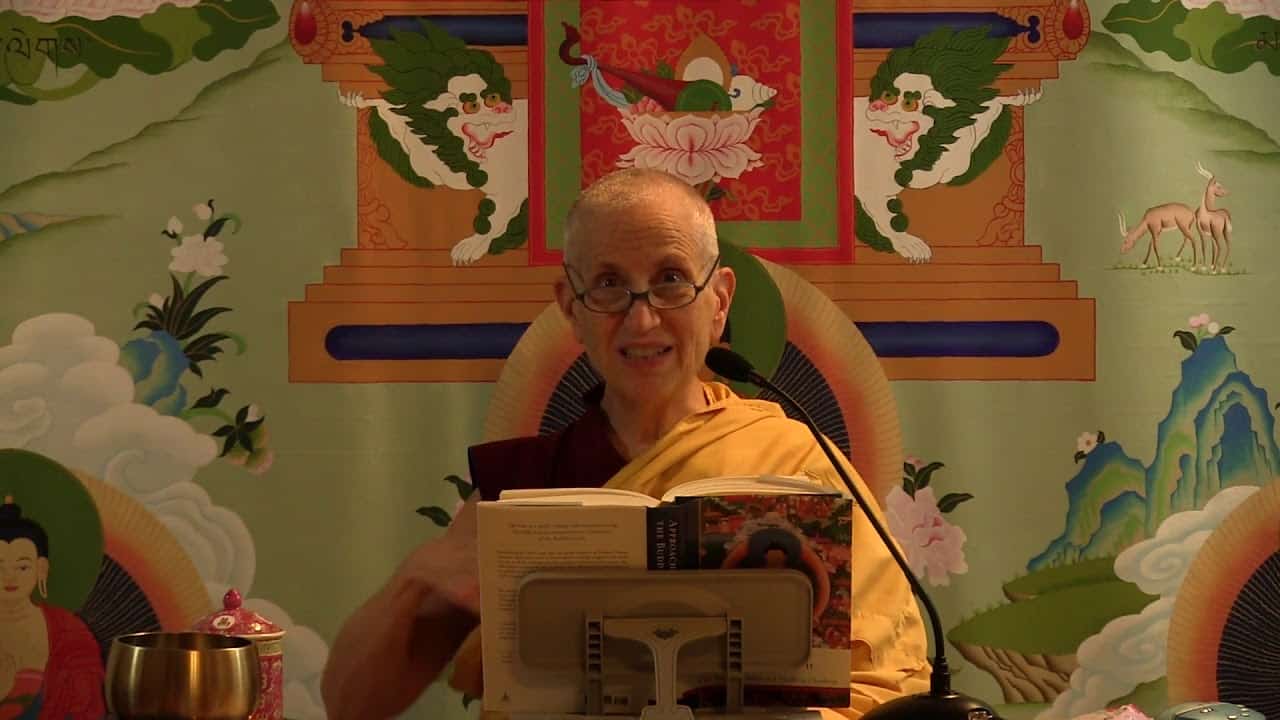

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.