The emptiness of identities and nonvirtue

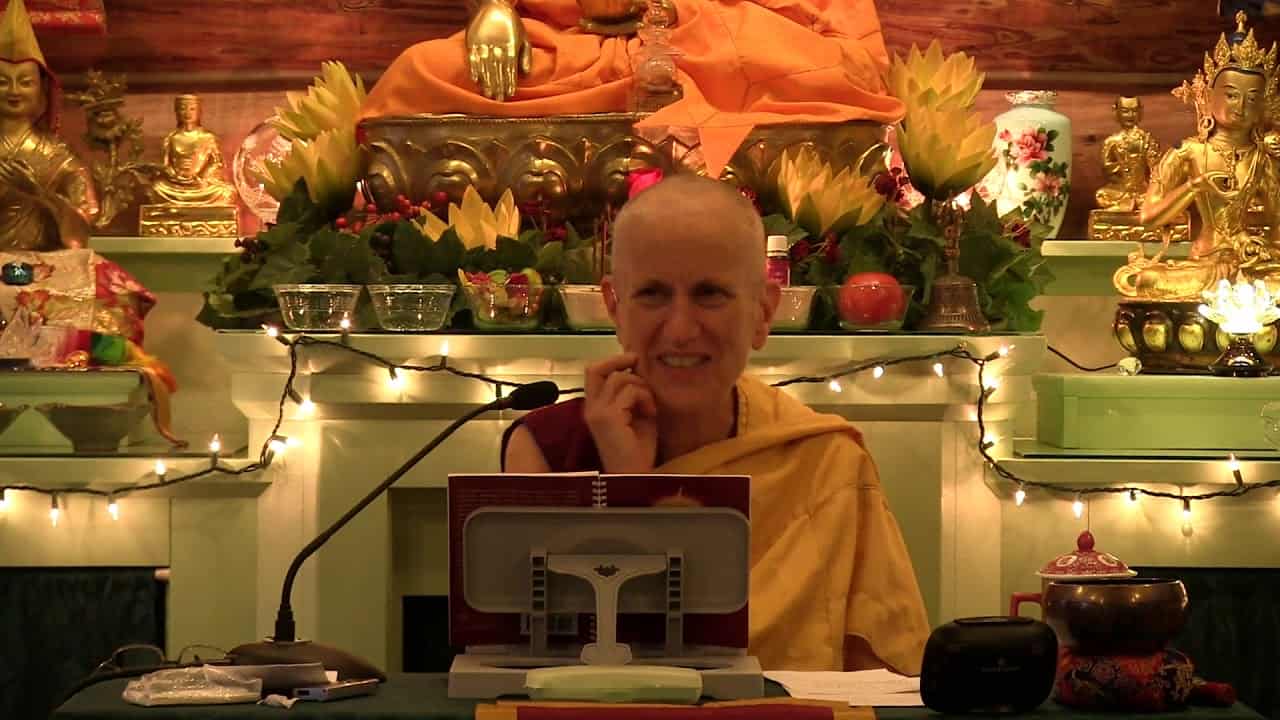

07 Vajrasattva Retreat: The Emptiness of Identities and Nonvirtue

Part of a series of teachings given during the Vajrasattva New Year’s Retreat at Sravasti Abbey at the end of 2018.

- Emptiness and conceptual constructions

- Identities exist within context

- The two extremes

- Who do we think we are?

- Grasping at the body

- Hiding our non-virtuous actions

- The emptiness of our non-virtuous actions

- Emptiness and dependent-arising are not contradictory

So, here we are in the last day of the retreat, or on the last day of this retreat. It’ll become the first day of the one-month retreat. The last and the first go together, don’t they? We think about that sometimes, like, dying is an end, but dying is just a transition. It’s an end, and it’s a beginning. What makes it scary is that we grasp onto our identity, we grasp onto our possessions, onto our friends and relatives, onto our body. All of this me, all of this is mine, and I don’t want it to change. Yet the reality is change. That’s why understanding dependent arising is important, because it helps us understand that things are transient, and they don’t stay the same in our lives. Dependent arising also helps us to see that there’s no actual self there to grab onto. Some people may not like that idea. When you cling strongly to your identities, you don’t like that idea.

When you really are able to look at your own experience and see that clinging to identities is what keeps us cycling in samsara, then you begin to see, “Oh, there’s some value here in releasing identities.” It’s seeing, yes, things exist, but they don’t exist in the way that I think they do. They exist dependently, but there’s nothing there that I can identify as me. When you search, there is nothing you can identify as me. You’re saying, “Huh? But I’m sitting here, and I have a passport, and a driver’s license, and a birth certificate. I can prove that I exist, and I am here. Don’t mix me up with anybody else, even though there may be 5,000 of us if you Google my name. I am still me.” We hang onto that so much, but what are you going to identify as me? When you look… let’s spend some time with the body because this is something we hold very strongly to. So much of our identities, as we discovered the other day, are based on the body. We defend those identities, and they do have some functional existence in a certain environment.

I’m just going to backtrack for a minute about that because I was thinking a little bit about, we were talking about race and ethnicity and that kind of stuff, and I was thinking, that way of talking about it, that way of looking at it, is very unique to the US, and to certain parts of the US. It’s a West Coast, Northeast phenomena. Don’t go to Nebraska and expect them to think like this. Same with gender things. In different cultures, the whole idea of gender is completely different, and the whole idea even of democracy being the best form of government. That isn’t prevalent throughout the world. That was one thing I really had to get used to when I first went to Asia; well no, the second time I went to Asia, but the first in the monastery, was that in the monastery they didn’t think democracy was the best way to run the monastery. I’m going, “What?! Democracy is the best!” I’m looking at how they do things, they don’t think that. It really made me stop and look at my cultural assumptions that I thought were THE way.

Democracy has some good qualities, but we’re also on the what number day of a government shutdown with no relief in sight, and this is a function of democracy. Does that work? I’m not advocating for autocracy, certainly by no means, but what I’m saying is that I had to really, by living in other countries, readjust my way of thinking that there’s one way of government that is the best for everybody and everybody should do it that way. Or, there’s one way that society should function, and everybody should do it that way, because that just isn’t the case.

Things function within an environment, not just independently on their own. It’s the same with us. We have our identities dependent on the environment that we live in and what kind of sentient being we are. We happen to be born in the human realm this lifetime, this particular karmic bubble. All we are is a karmic bubble. Because of that, then we notice different things, we think different things, we construct different things. This isn’t the same for all sentient beings, social structures and things like that. I was thinking about our cats. Cats are great teachers around here. Upekkha is pretty dark, Maitri and Mudita are grey, and Karuna is mostly white, but not totally. Do they rank themselves according to the color of their fur? I don’t think that the color of the fur is really important to the other kitties. I don’t know if you’ve noticed our turkeys. Most of the turkeys are brown-black and there is one white turkey and the one white turkey fits in with the rest of the turkeys. Nobody’s pecking on that one turkey because they look different from the others. This is what I mean when I say that things exist in an environment, in a context. Outside of that context nobody cares.

If you look at our whole economy—and people are so freaked out—the stock market’s up and down, it’s like we’re on a ride at Disneyland. Where did the economy come from? Everybody latches onto it. Where did the economy come from? We made it up. We made up a banking system, we made up a stock market, we made up bonds, we made up interest rates, we made up savings accounts and checking accounts. The whole thing is a human fabrication. We fabricated it and now we suffer within it. Isn’t that interesting? We fabricate the whole thing, and then because we are taking it as so real, then we suffer.

Manners, similarly. What are considered polite manners in one culture are rude is another culture. When young husbands met the British, whatever rank he was, led his men into Lhasa in the early 1900s, the Tibetans were standing around the Lingkhor—one of the big places where you circumambulate—and as the troops were marching in, the Tibetans were clapping. The British thought, “They are welcoming us,” because clapping in Britain is a sign of approval, and welcome, and we’re glad you’re here. In Tibet, clapping is to scare away the demons. They were not welcoming the British with open arms, they were trying to scare away the demons. In Western culture, it’s very rude to stick out your tongue. In Tibetan culture, that’s how you really show respect to somebody because you bend over and stick out your tongue. I can’t do it perfectly, but it is a sign of respect to somebody and it means, by showing your tongue, that you don’t have any kind of black magic mantra that you are using. In the West, we shake hands with our right hand. It’s to show that you don’t have a gun in your hand, that’s the meaning of it. It’s from the Wild West, which exists today. It’s an old tradition that exists today. It shows you don’t have a gun in your hand, you reach out your empty hand to shake.

These things exist within cultures and what we consider polite and rude is not inherently existent, it depends on the culture that you are in. That’s looking at some ways in which we concretize things and then get upset with each other. In Tibetan culture it is very rude to blow your nose, to take a tissue and blow your nose. You have to cover your head like this and then blow your nose. I had hay fever. I spent a great deal of time in my Dharma classes like this. Now, in America, in the West, is it polite in a class or in front of people? In our culture, no way. They’ll make a law against it. If they won’t let Islamic women wear their scarves, they’re certainly not going to let Tibetans blow their nose under their robes. Yet, not doing that in Tibetan culture is considered very rude. What I’m trying to get you to see is how we construct things, and then based on what we construct, we judge other people assuming that they have the same social constructs that we do. That assumption, if you go back to Thursday night, is not a correct assumption. You have to back step it, it’s a wrong view. It’s not even a kind of doubt, it’s definitely a wrong view. By not seeing this kind of thing, we get into so much trouble.

We were talking about cultural appropriation one day at the Abbey and how—I think it was near Halloween, wasn’t it?—how people, if you dressed up as a Mexican, what’s that? The name’s slipping my mind…

Audience: Mariachi

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Mariachi, thank you, that go around and serenade people. That is cultural appropriation, you’re not supposed to do that. Then, Ven. Nyima was sharing that when she was younger, she’s from Colombia, that when people wanted to learn about Hispanic things, she felt really good and she felt it was a coming together and anything but cultural appropriation. You can see just within one country how things have changed, and also, it’s only in some parts of the country. In other parts of the country, and with other people, I would assume now if people asked how to cook Spanish/Latino food, you would be very happy. You wouldn’t consider it cultural appropriation. You just learned how to cook Chinese food. I don’t think you’d consider it cultural appropriation. How different people see things in different ways, and if we just have this assumption that there’s one way because our particular niche thinks about things in that way, therefore everybody thinks in that way, then we are not going to get along with other groups very well.

This is, I think, one of the lessons from that book Strangers in their Own Land. I’m talking about dependent arising and how things are empty of having their own inherent meaning, on one level. If we go back at a deeper level, question not just, “Am I inherently this race or that race, this nationality or that nationality,” that’s on a more superficial level. Let’s look. Is there a concrete ‘I’ to start with? When we’re saying, “I’m this religion, I’m that cultural group, I’m this age, I’m this ability level, I’m this artistic,” all these things, we’re already doing that on the assumption that there is a real solid self, the essence of ‘me-ness.’ We’re doing all that on that basis, and we don’t even question that basis. In fact, when somebody brings it up, we get a little bit nervous, “What do you mean there’s no soul, there’s no essence of me? When I die there’s got to be something that I am.” We think if there’s not something that is permanently me, then the only other alternative is total nonexistence, and that freaks us out.

What Buddhism is saying is, it’s not either of those extremes. It’s not the extreme of, “There is a real me who’s always me, who’s the essence of me-ness, that never changes, that’s always here.” There’s not that kind self that we need to protect. That’s one wrong view, holding that there’s that kind of self. The other wrong view is saying, “Well, if there’s not that kind of self, then I don’t exist at all, and everything is totally nonexistent.” Those are two extremes, you’ll find them. The technical terms are the extreme of absolutism and the extreme of nihilism. But we flip-flop. We hold onto this one, but when we negate this one, then we think, “Then there’s nobody.” Then we say, “But there has to be somebody, I’m sitting here in this room,” so then we go back to this side and say, “Okay, then there’s a real me.”

In the Vajrasattva practice, we’re doing the whole practice within the framework of trying to see that Vajrasattva, me, my negativities, the four opponent powers, everything we’re doing, the mantra, the whole thing, that all of that exists dependently, but none of it has any inherent, findable, isolatable, self-enclosed identity that makes it what it is. When we have this view of our self, sometimes you’re doing Vajrasattva and you feel, “I’ve done so much negativity, I’m just hopeless. I just have stockpiled negativity this life, I’ve made a mess of so many lives, and my life. The whole thing is hopeless, and then they tell me there’s previous lives, and I botched it up just as much in previous lives, and I’m just…”

This is where you get—what is it in Catholicism—original sin. There’s original sin, I am inherently flawed, I can’t do anything to change that situation. Somebody else—but I don’t know how it’s supposed to happen—makes it all better again. But I, myself, inherently flawed, can’t change, can’t do anything. Even if I repent and beat my breast, that can’t cure the whole thing. That is grasping onto inherent existence. That’s grasping onto a real concrete me with real concrete characteristics such as being 102 percent flawed. Not just 100 percent. 102 percent. Make sure nothing ever changes. Then we go through life with that vision of ourselves, and that vision of ourselves limits our abilities because when we have that view of ourselves, then we don’t try because we’re already defeated before we give ourselves a chance. We give up on ourselves, basically, by holding onto that kind of belief that there’s a real me who’s evil, who’s bad, and it can’t change, and the whole thing is hopeless. So then, let’s go to the bar with all the people who aren’t taking the fifth precept, and we’ll celebrate all the other people who are taking all five precepts. I have to needle you a little bit, don’t I?

Audience: I get the idea he took the fifth precept.

VTC: Yes, I know he took the fifth. I gave it to him. But I also know how difficult it was for him to do that, and also how beneficial it was.

This grasping at a real me, this is the root of our confusion and the root of our suffering. Why do we keep taking one rebirth after another in samsara, again and again and again and again? Like being on a merry-go-round that goes up and down and you can’t get off. What’s the root of that? It’s the grasping at there being a real, solid, self-enclosed, individual, independent me or I or self. Once we have that idea, then of course we have to protect that self, because if there’s me here and the rest of the world out there, then that rest of the world can either give me pleasure or it can give me pain. Some people are really interested in the pleasure part and, “Let’s get the pleasure.” You have greed, attachment, “I’ve got to get this and this and this,” leading to negativities, negative karma, leading to rebirth. Other people, it’s like, “Yeah, I want all of this, but really I have to defend myself because those people out there, they can really hurt me.” We build up walls and we defend them with anger, animosity, hostility.

Most of us are a combination of those two. We look at other people and we compare ourselves to them. Comparison is deadly. Our whole society is founded on comparison and competition, isn’t it? But it’s deadly, because every time I compare myself with somebody else, I don’t cut the grade. Then I get jealous of them because they are better than me. Or, I compare myself to them and I’m better. Then I lord it over other people and oppress them. Then we get into all these other machinations of, “I don’t feel like doing it.” Do you know that? “I don’t feel like doing it. I want to lie around today. I want to do something fun today. Anyway, it all doesn’t matter. Nobody cares. I can’t do anything.” That’s laziness from a Buddhist sense. You can see it, that all these problems in the world, they are all traced back to the root of reifying ourselves and reifying everything and everyone else around us.

Again, our mind creates these inherently existent people, inherently existent pleasure and pain. Then we fight against what our own mind has created. If this isn’t a cause for compassion, I don’t know what is. Here we all are. We want to be happy. We don’t want to suffer. But based on this fundamental ignorance, what do we do. We create the causes for suffering again and again and again. We chase after what we want, and we’ll do anything to get it. We can’t stand these things, and we’ve got to destroy it. Then there we go, the story of lifetime after lifetime after lifetime in samsara. This is why questioning that fundamental identity is so important, because that’s the key to liberating us, that’s the key. We have to start questioning the more superficial levels of how we concretize things, but always remember to go back to that fundamental level, too, and question that and investigate that. Who am I?

Another one of my mother’s good things, her sayings: “Young lady, just who do you think you are?” That was a good question; she started asking these since I was a little kid. I didn’t take it the Dharma way. I should have. I realize now she was actually teaching me emptiness even though she didn’t even believe it, but it’s true. Who do you think you are? Who do I think I am? The first thing we think we are is our body, because we’re so entranced with desire objects, with external objects. There are three realms in cyclic existence; ours is the desire realm. The thing in the desire realm is there’s all these external objects that are so desirable, and by some being desirable, there are also others that are harmful. But we’re totally entranced with all these external things. From the time we open our eyes in the morning, just always sense objects. There’s me and a sense object. There’s me and another person. How do I navigate my way through all of this so that I can make this self happy, preserve this self-identity and dignity, prevent the self from experiencing any harm? Because there’s a real self, and to prove it, I have a body.

Look at science. What does science investigate? You talk about the brain, the body, science explodes with things. The mind? Let’s change the subject. They’re really stumped about the mind, something that isn’t material because we are so like, “I’ve got to understand all of this.” NASA just found some big chunk of ice, some billions of miles away from the earth, the furthest visible thing that’s beyond Pluto. They send something out to it and we’re going to get data that’s going to help us understand this big ice cube. I’m not sure if it’s rotating the sun or what it is, but they just sent something out and it made contact. They’re going to have data by Tuesday. And this is going to help us as human beings, because everything external is so entrancing, isn’t it? I mean, look how you relate to your phone. It’s part of your body almost. You come here and Ven. Samten says, “Give me your phone.” You’re like this, “You’re asking me to cut off my hand!”

Audience: A lot of people didn’t turn in their phones.

VTC: Then they don’t get the clickers for counting the mantra either. No phone, no clicker. No clicker, no phone.

What we’re getting at is how entranced we are by external things, and it starts with the body. I am this body. Don’t you feel that? I am this body. I’m here because the body is sitting here. It’s interesting because sometimes we think, “I am the body.” The body’s here, I’m here. Sometimes, we say, “I have a body,” as if the body is our possession, not who we are. Sometimes, we say, “I am old,” or, “I am young.” “I am that.” Sometimes we might say, “I have an old body,” but that sounds strange to say, doesn’t it? If you have an old body, it means you are old. We go back and forth between identifying, “I am the body,” and, “the body is my possession.” We hold both of them as if they are inherently real. But even that thing of holding one ‘I am’ and one ‘I have’ indicates that we don’t completely believe… I mean, if we say, “I have a body,” then we’re already at some level saying, “I’m not my body.” The body is something else.

We’re really actually pretty confused about how to relate to our body. Is our body me or is our body a possession that I have? Either way, whether it’s me or whether it’s my best possession ever, this thing made of blood and guts that is going to soon be a corpse is my most prized possession. Right? I don’t want to separate from it. [kissing sound] But what is it? What is it made of? “Oh, but my body is so beautiful.” Yeah, it’s so beautiful. We vomit, we pee, we poo, we sweat. Look at what comes out of every orifice in our body, and yet our body is so beautiful and so pure and other people’s bodies, same way. Look at that liver. Are you getting some idea of what ignorance is? How our ordinary view of things somehow doesn’t actually hit the spot of what things are? We have to question, who is this ‘I’ that did all these negative actions? We have this notion that there is a concrete ‘me’ who did those negative actions, who’s sinful through and through, or evil, or contaminated, through and through. Think of the negative action you did some time ago. Anybody have an example?

Audience: I’m not going to tell you.

VTC: That’s our problem, you see? Our negativities are me. I’ve got to hide my negativities because if other people know about them, then they won’t think I’m wonderful. Then they’ll know the reality about me. Let’s hide it all, even though we all know that we’ve all committed negativities, don’t we? Except those of you in this audience who are arhats and bodhisattvas—well, even those who are, you were once sentient beings—so everybody in this room has committed all ten non-virtuous actions at one time or another since beginningless time. That’s a given. We already know that about each other. What are we hiding? You know I’ve committed all ten. I know you’ve committed all ten. You know I’ve broken precepts. I know you’ve broken precepts. But…

It’s amazing, isn’t it? It’s totally amazing, so funny how we are. So, just to begin to question all of this, and not only am I not my body and not my mind, but Vajrasattva also isn’t some kind of concrete thing. Like we talked about yesterday, there’s not Vajrasattva sitting up there next to God, the Old Testament God, or the New Testament, too, they both are pretty judgmental. I don’t think God changed that much between the New and the Old Testament, because he’s permanent anyway. But there’s Vajrasattva, inherently pure from the beginning; Vajrasattva was never a sentient being like me. He was born pure. No. All the Buddhas became Buddhas because they were once sentient beings and they’ve practiced the path, they purified their mind, they developed all the good qualities. They became a Buddha, they weren’t born that way. Similarly, if we practice the path, purify our mind, accumulate merit, follow the same thing they did, we’re going to become Buddhas. Maybe you’re a Buddha, one face, two arms, holding a cell phone.

This thing [of], there’s Vajrasattva up there, self-enclosed, pure from his own side, he’s never been a sentient being, and always just sitting there as Vajrasattva. Poor guy never moves, either his hands are always like this or his hands are always like this, forever and ever, never moves, never does anything. And we go, “Uh, I don’t want to become like that. How boring.” Like she said, I’m going to sit there all day, “Om Vajrasattva samaya… When are these sentient beings going to get it together?” Vajrasattva’s not some frozen, inherently existent person, concrete, sitting up there, looking and saying, “Oh, evil,” looking at us with so much judgement. That’s not what’s going on. Vajrasattva exists by being merely designated on that appearance of body and mind; we exist by being merely designated on merely the appearance of body and mind.

We can all generate that kind of wisdom, and when we have that wisdom, then we see that although on the conventional, superficial level things appear, there’s all different kinds of things that arise because they have different causes and conditions. But on the level of what our fundamental nature is, our ultimate nature, at the end you can’t find any inherently existent person, any inherently existent thing that is afflictive, any inherently thing that is purified. Everything exists in a context, in relationship to each other. Even that emptiness exists in relationship to the conventional objects. It’s not that emptiness, the ultimate nature, is some kind of concrete reality that’s fifteen universes up and five universes to the right, and we’ve got to go there. The emptiness is the nature of every single thing: you, me, everything single thing around us. It’s right here, we just don’t see it.

When we’re doing the Vajrasattva purification, this loosening how we conceive of everything is very important. Even when we think about our negativities, “Oh, I did this horrible negative action. I lied to somebody,” let’s say. We look at lying, concrete, this is how it appears to our mind, concrete, that is a lie. All four factors that are necessary to make it a complete object of lying are present. There was an object, there was an intention, there was the action, there was the completion of the action. There’s the karma of lying, and I’ve done it. There’s a real me. There’s a real action of lying. Then we start to investigate. If we take that action of lying, what was it really? If something is concrete like that, we should be able to identify exactly what it is. Exactly what is that lie that we are so contaminated by having done? Is the lie the motivation? Is the lie the movement of your mouth? Is the lie the sound waves? Is the lie when you first opened your mouth and started speaking, or is the lie the sound waves that came out in the middle, or is the lie the last bit of sound waves? Maybe the lie is the first moment of the motivation when it was still weak, or maybe it was the last moment of the motivation when it was strong? When you start analyzing the lie, what exactly was it? When you do this, can you find some concrete inherently existent lie that you did?

You can’t find anything, can you? If there were a real lie, the way it appears to us, we should be able to identify it. It’s right there and you can see it stinks through and through. But when we analyze to look for what the lie is, it’s like sand going through your hand, isn’t it? It’s like, there’s a lie there, but I can’t find it. Then you have to realize, actually, there is no inherently existent lie. There’s a lie on the level of appearance, when I put all those different moments of different activities of body, speech, and mind together, but I can’t even find which moment starts the lie and which moment ends the lie, when you analyze it. Which moment starts the lie? Oh, the first moment of my intention. Can you find the first moment of your intention? Was there a first moment of intention, before which there was nothing?

Did that first moment come out of nowhere? Maybe it was the first moment of moving my mouth. When was the first moment of moving my mouth? Is it [makes gesture]? What is the first? If it’s moving my mouth, but what about my vocal cords? Just moving my mouth isn’t lying, it has to be my vocal cords. My vocal cords aren’t going to move unless I have the intention, but I’m not going to have the intention unless there’s all this other framework laid out beforehand, like a need to defend myself and blah blah.

The point is, without investigating, it looks like there’s a real, solid lie. Negative action. But when we investigate, we can’t find exactly what it is. When we don’t investigate, there’s the appearance, [which] depends on many factors, and that appearance functions but it’s not something that exists from its own side, independent of everything else. It’s not inherently bad, so it can be purified. Something that is inherently existent can never be purified. Something that is a dependent arising, you change one factor or another factor, everything has to change. We want to, when we’re doing the Vajrasattva practice, remember that there’s no deed that exists as an independent agent from my own side. There’s no action that exists as an independent action from its own side. There’s no object that I’m acting upon that exists out there independent from its own side. They’re all interrelated.

When we don’t analyze, there’s the appearance. When we analyze, it evaporates. The appearance level, when we don’t analyze, is what we call conventional or veiled existence. The disappearance of that inherently existent thing when we do analyze, that emptiness is the ultimate nature. We have to be able to see both of them. Right now, we’re at the extreme of solidifying the appearance aspect, so it’s good to really work at deconstructing some of that and seeing how things are dependent and they lack any kind of nature of their own. Any kind of identity of their own. Then go from there to, “But they appear.” This way of meditating on emptiness and complementing it with the dependent arising, this is the ultimate factor that purifies the negative karma. When we’re talking about the remedial action—we’ve talked about it in terms of reciting the Buddha’s name, reciting the mantra, meditating on different things, offering service, helping charities, helping the poor and needy, and so on—the ultimate thing that really purifies the mind is to be able to see that ultimate nature, and to see that it is not contradictory with the appearance level. That’s not easy, but the more we can familiarize ourself even a little bit with this, the more it really helps us to relax and to not take things so seriously.

Audience: I’m thinking about the non-existence of the lie. Within our purification practice, we do actually give a specified action or frame of mind a particular name in order to enact the purification, so we’re giving it an existence by naming it, but it doesn’t have inherent existence.

VTC: Right. It exists by mere name.

Audience: By mere name, but not inherently.

VTC: But not inherently.

Let’s sit in silent meditation and think about what you heard. Explore a little bit, who do I think I am and what exactly is this negativity? How do I conceive of all these things, and do my conceptions have anything to do with how things actually exist when I investigate how things exist?

Just some closing advice. You’ve been in a very good habit the last few days, practicing morning and evening, holding good ethical conduct. Take the habit that you’ve been developing here home with you. Don’t think, “I’m going home so I can’t practice, and I’ve got to moderate my ethical conduct in some way,” and so on and so forth. You’re going in a good direction, keep going in that direction when you go home, those of you who are leaving. Also, be aware that although it may seem that your mind is still quite noisy, it’s actually a lot quieter than it was when you came. When you leave, don’t just get in the car and turn on the radio and check your cell phone in one hand and your tablet in the other, and the radio going, and driving the car, multitasking and everything, and thinking of everything that you have to do that you weren’t able to do because you took these days off, getting yourself built up in anxiety again. Everything will just happen, it’s okay, go slowly, do your practice, be kind. Really watch how you’re relating to the media and the sense objects that you encounter. Don’t just head for Starbucks and the steakhouse. Please come back and share the Dharma with us again, you’re part of the Sravasti Abbey extended community.

We have the retreat from afar going on for the next few months, where people at home do one session of the Vajrasattva practice even though we’re doing multi sessions here, and then you can send us a picture of the real you in a very beautiful pose and we’ll put it up on the wall in the dining room. It’s not one of these Buddhist dating apps up on the wall, so don’t go looking for, who am I going to contact who’s also doing Vajrasattva. Basically, just enjoy the Dharma and enjoy your lives and hold your values closely to your heart and live according to them, and then relax.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.