How purification works

06 Vajrasattva Retreat: How Purification Works

Part of a series of teachings given during the Vajrasattva New Year's Retreat at Sravasti Abbey at the end of 2018.

- The relationship between karma and afflictions

- Purification and the ripening of negative karma

- Giving our pain to the self-centered thought

- Visualizing and relating to Vajrasattva

- The relationship between merit and negative karma

- The Buddhas have unconditional acceptance and love

- Separating the Buddha’s teachings from culture and religious institutions

- Emptiness and the conventional self

We have a few questions here that I’ll try and answer and then we’ll go into the meditation like usual. Some people asked about the bodhisattva vows and taking them, and I was going to give that during the one-month retreat. The plan wasn’t to do it tomorrow. If you’ve already taken it, then you still have it and you should be renewing it every day by saying one of the verses to renew the bodhicitta. If you want to know how to observe them and the meaning of the different precepts, then I think that I’ve taught it a couple of times and I think it’s on the website. You can read on the website. Also, Dagpo Rinpoche has a very good book on it. It’s hard to get the book, but I referred to it in… we have it in the office don’t we? If people want that we can email that to you, but I referred to it when I taught them, so the meaning is there. Then also, somebody asked about taking the celibacy precept when they take the five lay precepts, and if you’re really certain you want to be celibate and have no sexual interaction at all, then when you take the five precepts you think of the third precept, which is usually to avoid unwise and unkind sexual behavior, you think of it as a celibacy precept and so you just take it in the context of taking the five precepts. Then, a little announcement for the people who are staying on next month, there’s a booklet that one of the incarcerated people I work with and I put together with different materials to help people reflect on their lives and the idea that they could use it in prison. One of our friends has done the layout and we need one or two people to proofread it, so if you’re interested in proofreading. We have lots of people, good.

When you do something non-virtuous, can it ripen in a mental affliction or vice versa? What connects one moment of an affliction to the next moment of manifest affliction? For example, if I’m mad this morning and then I’m not mad for the rest of the day and then in the evening I get mad again, it would say that it’s the seed of the affliction that connects the first moment to the second moment. This is because it wasn’t like anger just totally vanished from your mental continuum during that time. The seed of the anger was there even though the anger wasn’t there in the manifest form. It’s not that karma causes the afflictions. The karma doesn’t cause the afflictions because the karma is the actions we do. The actions we do leave seeds or imprints on the mindstream. The action itself doesn’t cause the affliction.

In terms of how it goes, it’s the affliction that causes the action. If I have anger in my mind, that causes the action of telling somebody off. If I have attachments in my mind, it produces the action of lying to get something that I want. It’s the afflictions that cause the karma. Then, one of the results of karma—because karma has four different kinds of results; well, three, but one is divided into two so you wind up with four—one is the realm you’re born into, the second is the experience that’s similar to the cause, or concordant with the cause—that’s the one that has two, I’ll come back to that one in a moment—and then the third one is the environmental result, the environment that you are born into. Those are the three results of a fully completed karmic action that’s either virtuous or non-virtuous. To be fully completed it needs four powers. Read either the book Good Karma, or it’s in Volume Two of Foundation of Buddhist Practice. This explains a lot about karma, so if you have questions read those two books, they’re helpful.

That second one—the result that’s concordant with the action—has two parts. One is that you experience something similar to what you caused somebody else to experience. The second part is that you have the habit of doing the same action again. That one is really deadly because it’s the habitual energy such that we keep doing the same nonvirtuous action repeatedly, which just accumulates a lot of negativity.

In the case of our virtuous actions, to have that habit of doing the same virtuous action again and again, that one’s good, but you can’t have one without the other and this is just the way it works. We may have the habit to, let’s say, be very uncooperative and just rude to people. If we do an action like that, then part of the result is the tendency to do that again. Although we have some mental actions, for example, coveting other people’s things, [or] malice, which is planning how we want to harm them, wrong views, these kinds of mental actions, then there’s some habit from doing them before, but the mental action is not just the affliction. It’s the affliction being in the mind for a longer time, its building on itself and getting ready to come out in terms of body and speech. For example, the negative mental action of malice isn’t just a moment of anger. A moment of anger is affliction, but the negative action of malice, it’s a mental action because you’re sitting there stewing, “This person did this to me, I want to get even, I want to harm them back.” It’s not just a moment of the affliction, but it’s that you’re ruminating on it and building on it, it may or may not come out in your physical or verbal actions.

So, just to be clear, it’s afflictions that cause karma, and then karma leaves the seeds or the imprints and those ripen in those four kinds of results that I just described. You got it? A little bit complicated? If you write it down, it’s not so complicated.

When you do purification, like circumambulation, does the power of the holy object cause karma to be purified quicker or negative results manifest quicker? I don’t think the power of the holy object causes karma to manifest quicker or things to happen quicker. I think the power of the holy object is just what they say, that even if you don’t have a particularly virtuous motivation, let’s say when you’re circumambulating a stupa, just by the power of coming in contact with that object it leaves virtuous imprints on the mind. That’s why they say it’s very good to circumambulate holy objects. It’s good to sponsor Dharma books, it’s good to look at the statues of Buddha, or have prayer wheels and turn them, and all these kinds of things.

If we reword the question in another way, does purification in general, like doing Vajrasattva or 35 Buddhas or whatever you’re doing, does it cause an action to bring its result quicker? What did she say, “Does it cause the karma to be purified quicker or negative results manifest quicker?” When you’re doing purification, sometimes you get sick, sometimes your mind is off-the-wall and wonky. These kinds of things happen when you’re doing strong purification. They say it’s a result of the purification because you’re really applying the four opponent powers in a very sincere way. Sometimes it happens that the karma can ripen very quickly and in a way that is not as strong as it would have if we had not done purification. For example, I had a friend who was doing a purification practice at Kopan, one nun, and she got a very bad boil on her cheek. It was a really big boil. She was walking around one day—I forget if it was Lama or Rinpoche, probably Rinpoche who gave this particular answer—and he said, “What happened?” and she said, “I have this boil,” and he said, “Fantastic.” She’s going, “Huh? Rinpoche, it’s big, it’s infected, it hurts.” “Fantastic you have a boil!”

Why did he say fantastic? Because some negative karma was ripening, and it was finishing, and it would no longer be obscuring her mind. That karma ripening, because she was deliberately purifying at that time, could have been a karma that otherwise, if she hadn’t purified, may have ripened in, let’s say, being born in a lower rebirth for an eon or two or a couple of rebirths, or who knows for how long.

The idea is when we experience suffering like that in this life, if we see it as purification, then it becomes purification. If we just see it as my negative karma ripening, then it’s just negative karma ripening. It’s always good if you get sick, or something doesn’t go the way you want, or there’s an accident, or somebody criticizes you, or something like that, to say, “This is a result of my negative karma. It’s ripening now, how fortunate I am! This person just told me off, I am so fortunate!” Why? Because that karma could have ripened in a really horrible rebirth otherwise. If you think about the unpleasant things that happened to you in this life in that way, then you see that actually, you can deal with the suffering that came. It’s not a big deal.

Compared to a rebirth in the lower realms, getting sick is nothing. You just kind of say, “Okay, I’m sick. It beats having a horrible rebirth and I’m glad this is happening.” By the power of your thinking in that way, it becomes very strong purification. Whereas instead, if you think, “Oh, this person told me off, nobody loves me, this is always the case, people are criticizing me when I didn’t do anything wrong. I am so angry, I’m so hurt, I can’t even get to my meditation cushion I’m so upset.” If that’s your reaction to somebody telling you off, then what kind of karma are you creating? Negative karma, isn’t it? Rejoicing when this kind of stuff happens is actually, it’s very good for us now because it prevents us from getting unhappy and distressed and depressed. By thinking in that way, we really transform the karmic result, which could have been big [to] become something small. Then we realize, I can handle this situation. If we don’t think like that, we go off into our melodrama, but if we think like that, “Oh, I can handle this, this is okay.”

I’ll tell you a story. In 1987, the summer, we went to Tibet. Venerable Sangye Khadro was mentioning that the other day. I was with the attendant of one of my teachers—my teacher had died—and his previous life’s relatives. We were going to Lhamo Lat-so, the prophetic lake where they often go when they’re looking for the new Dalai Lama. They look in the lake and they see signs and symbols and letters and things. We were taking some horses there. There was a western monk, I won’t mention his name, some of you know him. There was just a small group of us, maybe like six or seven people, so he was one of them. We were on horses and his horse was very uncooperative and we would get in the middle of a stream and his horse would stop. He was not a particularly easy-going person, so this really caused him a lot of distress.

I had a very nice horse. One time, after his horse refused to go anywhere in the middle of the stream, once we got across I said, “I’m happy to change horses with you. I’ll ride your horse and you’ll ride my horse because I’m okay standing in the middle of the stream for a while.” I offered that with a kind heart. He exploded at me. “Why are you doing this? We’ve worked together for years and you’re always doing this kind of thing. Even so-and-so told me when they were working together with you at this Dharma center how terrible you were.” On and on, I mean, really big-time and all I did was try and do something kind. He exploded. Usually, I hate being criticized. It’s one of my least favorite things, like most people.

I just listened and there was one technique that Lama Zopa had taught us—because it’s very important to not think our self-centered mind is us, but to think our self-centered mind is something out there that’s disturbing us. The technique is, when somebody is telling you off, you give all the pain to this self-centered thought, so instead of getting upset on oneself, you just give all the turmoil, all the pain, to the self-centered thought. “Here, self-centered thought, you take that, you take that.” Anyway, if somebody is criticizing you for your faults, why do we have those faults? Self-centered thought. So, it’s right that it goes to that thought. He’s sitting there saying, “Grumble, grumble,” and this technique, what Rinpoche had taught us, popped into my mind at that moment. I had heard it before, but I had never practiced it. It was on my notes that you put on the top shelf and don’t look at. I just said, “Okay, here he is blaming me one thing after the other, for things that happened years ago,” that he even heard about, and I can’t even remember. I just said, “Okay, it’s going all to the self-centered thought. Every single word of it is going to the self-centered thought.” I sat there and listened. Then we continued on our journey, he didn’t accept my offer. We got to where we were staying that night and my mind was completely smooth. It was like I wasn’t upset at all, which was astounding because like I said, I don’t like getting criticized and it usually makes me quite upset. This is the kind of thing, when you do something that’s purifying, then that kind of thing happens.

That story doesn’t go very well with what I was explaining. I don’t know why I told it to you. Okay, I should tell you another story! But it’s a good story, isn’t it? It’s a good story. Otherwise, I would have been so bummed out on that pilgrimage because we were days together, this small group of us. The story, many of you have heard this before, too bad. I don’t need to tell you a particular story about this, but this is the kind of thing I regularly do. Even if I trip and I stumble or I get sick or whatever, then I just now, kind of as a matter of habit—I don’t always remember but very often—I think, this is just the ripening of karma that could have ripened in something much more serious, much more horrible. I really got off easy. The thing of whether we purify or whether it’s just the karma ripening depends a lot on the way we think of the situation. It’s interesting, isn’t it? The situation is the same, but it becomes just ordinary ripening of karma or purifying a lot of karma, depending on the way we think, not on the situation, on the way we think.

Audience: Yesterday, I was helping out with something down at Tara’s, and in that I had a nail or a screw puncture my head. It was really gross and bloody. As we were talking, I realized I was purifying, working with the non-virtue of all the worms I killed fishing with hooks going in their heads. Is that the purification? It seems like it would be very obvious almost, or is it just kind of a coincidence that such a similar thing happened to the worms?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): That, you have to ask the Buddha. Those kinds of specific things, what’s the ripening of what kind of action, only the Buddha knows that. But, your thinking in that way transformed what happened to you into strong purification. Especially if you are regretting having gone fishing and killed all those fish.

Audience: It kind of freaked me out that it was so similar to what I was doing with the worms, except it was a screw and not a hook. It’s very strange.

VTC: It gives you some feeling for the pain the fish went through, except you didn’t get killed and fried. Thank goodness.

Audience: You mentioned negative unpleasant external events happening to you as being or ripening of negative karma. What about internal experiences, whether it’s anxiety or confusion or unclear foggy mind or depression?

VTC: I think some of that can also be the result of negative karma. They say, for example, if we’ve had a lot of malicious thoughts towards others, then in a future life we’re born in a way where we have a lot of suspicion of other people. We’re not relaxed around other people. If you make your teacher’s mind unhappy by doing negative actions or whatever, then it can ripen in terms of depression ourselves, or being very moody and unhappy ourselves. Yes, it can manifest mentally as well.

Audience: Can we go back and purify some actions that have happened in our past or does this purification have to happen in the moment?

VTC: Oh, no, that’s what we’re doing now. The whole Vajrasattva practice is about purifying things we’ve done in the past. Even in past lives. You just take the whole kit and caboodle and think about it and want to purify it and go through the four opponent powers. It’s a practice that I think is very psychologically healthy for us, because when we don’t purify, then all these experiences weigh on us mentally and we get bitter, we get cynical, and so on. Whereas if we purify our negative actions, then we put them down and we can go on in our lives with a much more upbeat, optimistic attitude.

Audience: Can we purify proactively?

VTC: Like, I’m going to spray my house and kill all those cockroaches, so I’m going to purify it before I do it?

Audience: Not something that’s intentional, but you know that you are probably going to do something so you’re putting out some good purification.

VTC: You can’t purify before you do it, but you can lessen the strength of the karma when you do it. Like, if you know you’re going to fumigate—and I don’t recommend this, I am not sanctioning this at all—but some people come to me, “I’m going to fumigate no matter what you tell me.” Okay. I don’t agree, but at least have some regret when you are doing it. Don’t do it with glee, “Oh, how many bugs I am killing!” It’s, “I really regret it.” That makes the karma less strong and then you still have to purify afterwards.

Audience: This is more of a comment than a question, just on a personal note. What I’ve noticed for myself in my practice through the years is that, at first, I would think by doing Vajrasattva, if I had a pretty intense heavy karma that I wanted to purify, that it would lessen almost immediately. I would get discouraged because I would keep doing Vajrasattva and I’d think, “Why isn’t this working?” Now I’m finding it just kind of starts to loosen its grip, and it’s really quite profound, actually. It just takes time.

Audience: This is slightly shifting gears, but I’m hoping maybe it’ll help some other people, too. In the practice, I’m finding it hard-ish to generate a clear vision of Vajrasattva. When I’m doing things with Shakyamuni Buddha, that’s way easier for some reason. I was wondering if you could give any tips. I feel like I’m not super connected with Vajrasattva, I don’t think I understand Vajrasattva the way I understand… like when I do the meditation on the Buddha, it’s so clear, but with Vajrasattva… I was wondering if you had any background or any tips or ideas to help with the visualization?

VTC: I think a lot of this has to do with just familiarity, that you haven’t done the Vajrasattva practice before, or you haven’t done it much before. There’s not that feeling of strong connection, the visualization isn’t clear. It’s like when you just meet somebody, you’re not going to remember their face very clearly, you don’t feel connected to them, but the more you meet them and talk to them, then you remember what their face looks like and you feel more connected. It’s like that.

Audience: Yes, I feel like, too, there’s an intellectual gap. I guess I don’t understand necessarily, when we talk about these different embodiments, where they come from or what they really are. So, I didn’t know if there were texts or anything to get a better sense of when we’re talking about… or a Tara, or whoever.

VTC: It’s more that you take the qualities of the enlightened mind, and because we cannot communicate directly with a Buddha’s omniscient mind, the Buddhas manifest in these physical appearances. The physical appearance expresses some of their qualities, and different Buddhas may have also made unshakeable resolves to help sentient beings in certain areas. Vajrasattva resolved to help us with purification; Tara with enlightening influence, that’s Green Tara; White Tara, long life; Manjushsri, wisdom; Chenrezig, compassion. They all have the same realizations, but they manifest in different ways to emphasize different aspects of the enlightened mind. You can see them as people, but I find it more helpful to really think of them as just manifestations of qualities. Instead of being people with a self, they’re the appearance of these qualities in a physical form. Kind of like an artist may have something in their heart and they paint something, or they express it in some way, it’s like that. The form bodies of the Buddha are expressions of these internal qualities. As we do the practice repeatedly, we become more familiar with it, the visualization becomes more familiar. We’re kind of getting to know that Buddha and forming a friendship.

Audience: I’m a little more interested now in merit and karma. During the Vinaya, when I introduced myself to Wu Yin, I told her that I had been married to a Japanese, and she goes, “Oh, you get so much merit for that!” and I thought, “Oh, I picked good, huh?” Almost better than 40,0000 miles on your mileage card. I was like, “Wow, I get all that merit but where is it going, and can I put that in my back pocket, and is it going to negate some of my negative karma?” Maybe you could…

VTC: I’d rather use another example.

Audience: I think she meant… your husband was Buddhist, right?

Audience: Yes.

Audience: So, the merit of being married to a Buddhist.

Audience: It was the Buddhist part, not the Japanese part? I was afraid to tell her that as I became more Buddhist, he became more Christian, and I thought, “Now I’m going to get subtracted somehow.”

VTC: So your question is…? No, I can’t solve your marital problems.

Audience: More of the relationship between the merit you gain and the negative karma you create.

VTC: Creating merit, or virtuous karma, again, this is a little bit difficult. Sometimes, in some cases, it acts as a force against the ripening of a nonvirtuous karma. In other cases, it’s just—I mean it does that, but it also plants the imprint in your mind for good results to come about. How much it overpowers, if it’s 52%? Put that on the list for the Buddha. I can’t tell you that.

Audience: Can I just clarify really quickly? When you said that the difference between just a normal ripening of karma and a purification is how we define it…

VTC: How we think, not how we define it. Do I say, “Oh good, I’m purifying a negative karma, I’m glad this is happening.” Do we say that, or do we say, “What the beep, beep, beep is happening to me? Why is this happening? It’s not fair,” in which case there’s no purification and, in fact, there’s creation of negative karma.

Audience: Sorry to ask so many questions. This is actually kind of the opposite of your question, which is when I visualize Vajrasattva—and this happened in the six-session guru yoga, too—it’s hugely powerful and I feel so much of a bond and I’m so connected. And I’m pretty sure that the Buddha of purification would not approve of me in general, so is that just delusional? Am I just projecting?

VTC: You’re not thinking in the right way. First of all, Buddhas don’t judge us. They’re fully awakened beings. They have no anger. They have no judgement. They have no desire to put anybody else down. They look at us only with compassion. Vajrasattva is looking at you with compassion. He’s not going “Oh, there she is, she did it again! Wow, you know she asked me to purify, I helped her to purify, and then that doesn’t happen.” That’s not happening! The Buddhas are very patient and tolerant. They realize that we go slowly. Vajrasattva is not disapproving of you or anything like that.

Audience: I was thinking it was a delusion on my side, from, “I’d really like him to like me…”

VTC: You don’t need to do ten back flips for Vajrasattva to like you either, because Vajrasattva has love and compassion for everybody, no matter how we act in return. All that samsaric way of looking at people, “Do they like me? Do they not like me? Oh, they don’t like me, I’m going to be kicked out. Vajrasattva’s going to go ‘blank’ because he doesn’t like me anymore.” That’s our ordinary way of thinking, and that doesn’t pertain to awakened beings. What it does show is how ingrained this distorted way of thinking is in our mind, and how we find it so difficult to imagine somebody looking at us with unconditional acceptance and with compassion. Even visualizing Vajrasattva looking at us that way, instantly we go into, “I don’t deserve it. I’m full of shame. I don’t deserve it. Something is wrong with me. This can’t be true.” This is all of our wrong conception mind operating. It’s a big bunch of garbage that has nothing to do with reality. Even with other living beings, we assume with other living beings, “Oh, they don’t like me, I did something wrong.” They don’t say good morning, “Oh, no, they’re mad at me, what did I do wrong?” We make up a whole story, and nothing happened. This is all the function of the self-centered mind. The self-centered mind has to always be the star, and if we’re not the best, we are the worst, and we’re the one everybody hates, the one everybody discriminates against, the one who is most unworthy, who is least valuable, on and on and on. You can write out, I’m sure you have this whole script, a bunch of garbage that we tell ourselves, that we believe. We have to get rid of all that stuff because it’s not true.

Audience: I should cry for emphasis.

Audience: When I am visualizing Vajrasattva and experiencing those qualities as you described, for whatever reason, I experience that being as very neutral, not particularly a male Buddha or a female Buddha. Like when I visualize Tara, my experience of her qualities seem to be much more in the feminine. I find that beneficial, but I don’t know if that’s just my own projection or if that is how that particular Buddha is purposely depicted and I happen to be picking up on that.

VTC: I think Buddhas basically are androgynous. They appear in different forms. The thing that’s important is not, do they appear in a male form or a female form, because look at what happens if we think of them as strongly male or female. We project all this stuff on them. Oh, Vajrasattva’s male therefore blah, blah, blah. And Tara’s female therefore blah, blah, blah. Actually, those are just external forms. Buddhas have no gender.

Audience: I agree, except on the Thangkas or in our visualizations, those particular qualitative expressions do have forms that sometimes cue us to experience them as more stereotypically feminine or masculine.

VTC: We do have that response, but it also provides the opportunity for us to ask ourselves, what do we mean by masculine and what do we mean by feminine? That kind of, “This is masculine this is feminine,” I don’t know. Sometimes that kind of stuff just doesn’t resonate with me. It’s like, we’re human beings. They say women are so emotional. I’ve been around a lot of emotional men. I’ve been with men sobbing theirs eyes out. Don’t tell me women are so emotional.

Audience: Something related that we talked about yesterday, if I can ask, is when you went to Tibet and you wanted to learn more and there was some discrimination for being a woman.

VTC: Oh, this is in the Tibetan community in India.

Audience: I’m just curious if you can share, when you went through that, how did you react in terms of… if I was you and went there and I was dedicated to learning more and I see from the community that behavior, I could have some struggle, doubt, to the entire Buddhism. So just wondering…

VTC: How I dealt with it, yeah. For some people it causes doubt, but for me, the truth of the teachings that I was hearing was irrefutable. I separated in my mind the purity of the Buddha’s teaching from the culture in which it was embedded. They are two different things, and Buddhism always exists within a culture. That doesn’t mean I need to agree with everything in that culture, but the teachings themselves are pure, and if I practice them rightly, correctly, they’ll lead me to awakening. I just kind of separated those things out.

Another thing that I found I had to separate, is I separated out the Buddhadharma from religious institutions. The Buddhadharma is one thing, fantastic. Religious institutions, they were established by human beings, there’s politics, there’s blah blah. They are two different things. My refuge is in the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, my refuge is not in a particular group or institution. Another thing that helped me with this is I saw how my own mind was involved in creating the antipathy I felt.

One day, I was sitting there in Dharmsala where his His Holiness teaches, thousands of people there. This was many, many years ago, decades ago. We would offer tsok like we are doing tonight, and so during the tsok practice three people stand up with His Holiness. It was always three monks who stood up to offer His Holiness the plate and the substances, and then it was also the monks who distributed all the offerings to everybody in attendance. I was sitting there going, “It’s always the monks who get to do this. Why can’t the nuns ever be the ones that stand up and make the offering to His Holiness and distribute the offerings to the whole crowd? This is just total gender bias and discrimination.” Then, I imagined… in my imagination now it’s three nuns standing up and offering to His Holiness and then the nuns distributing everything. If that happened then I would think, “They make the nuns stand up to make the offerings and they make the nuns distribute the offerings. It’s always the nuns who have to stand up and work while the monks just sit there.” I saw this in my mind, and I said, “Uh-oh. My mind is having something to do with all of this.”

Audience: I’m new to visualizing a Buddha and imagining things coming from a specific being into my body. I’m a very conceptual person so what I’ve been doing that’s been working for me is imagining a source of energy or a light source that is the essence of purification coming into me, and not worrying so much about conceptualizing and seeing in my head a lotus, which I don’t really know very much about lotuses on a moon. I’m not trying to make fun of anything, I’m trying to describe my struggle because I’m trying to get the most out of the purification ceremony. To me, what I’m asking myself is, am I getting the purification? Is my intention of being purified by seeing the entity as white light?

VTC: I think it’s fine. Start with that because that resonates with you and that enables you to get… you can still go through the four opponent powers that way and you just think of that light as being the nature of wisdom and compassion. Then slowly as you continue practicing, then with time you can shift over and visualize Vajrasattva because then you’ll learn that the lotus symbolizes renunciation, the moon symbolizes bodhicitta. You get more familiar with some of these things, but that takes time.

Audience: Do those physical elements matter or is it what they symbolize that matters?

VTC: They’re connected. It’s the physical thing [that] is leading you to think in a certain way. I think for now what you’re doing is fine because the thing that’s important is that you have some experience of it. The whole thing with visualization, people always ask about that, I can’t visualize anything and it’s all blurry. It’s really just a thing of habit and familiarization. If I say pizza, do you have a visualization of pizza? Yeah.

Audience: If you said salad, I’d have a clearer visualization.

VTC: We have the capacity to visualize. It’s just, what are we habituated to visualize?

Audience: Hopefully this question isn’t as silly as the last one. You were talking about releasing our identities and this plays into becoming invisible to yourself. What I’m wondering is, when we become invisible to ourselves and do the emptying meditation, what’s left? Is there a self? An id or a soul, or do we have some kind of identity?

VTC: There’s no soul. There’s nothing that is an inherently existent me that we can draw a line around and say, “This is the essence of me that will never change.” From a Buddhist viewpoint that kind of thing doesn’t exist. There is a mental continuity. One moment of mind following the next moment of mind, always changing, never remaining the same. When we’re alive, when that mind stream joins with a body, then in dependence on that body-mind combination we give the designation I, but we’re not our body and we’re not our mind. There is an I there because we say I walk, I talk. I mean, you’re here sitting here in this room, aren’t you? But are you your body? No. Are you your mind? No. So, there’s person, but that person exists by merely being designated in dependence on the body and mind. It’s a little bit difficult to understand, but if you just remember there’s nothing that I can isolate and draw a line around and say, “That is a permanent ME. The essence of me that is special, that never changes.”

Audience: Yeah, I think you got it, with saying ‘essence.’ I think that’s what a lot of us feel, is we have some kind of essence that makes us us.

VTC: Yeah, and from a Buddhist viewpoint that is incorrect. Just because we feel it, doesn’t mean it exists. This is touching at the root of all of our problems, because we feel so strongly, “There’s a real me,” then we get attached to everything that gives that ‘me’ pleasure. We have hostility towards everything that interferes with the pleasure of that ‘I’ or self. There we go into samsara with all of our afflictions.

Audience: When you made the comment regarding separating out Buddhadharma from religious institutions… I’ve had the opportunity to live in different Buddhist countries and visit and experience them. As I’ve grown as a practitioner, I’ve really tried to assimilate that experience and make sense of it, also as a householder and having a family, contextualizing that and really defining the path for myself in a certain regard. I have always felt, though, uncertain as to how much I can do that. My question to you is, how far you go down the line to say, “That’s an institutional element, that’s a cultural element,” versus “This is Buddhadharma.” That, for myself, is a very, very challenging place to be whilst trying to stay true to my teachers, trying to stay true to the path.

VTC: This is a very important topic. I remember when I went to receive the full ordination in Taiwan in 1986, I had spent nine years already being a nun in the Tibetan system, and I had learned to sit for a long time, chant in Tibetan, do things the Tibetan way, my shoes all over the place. Then I went to Taiwan and you don’t sit for hour after hour there, you stand, and I couldn’t stand that long. Instead of chanting in Tibetan, you’re chanting in Chinese. Instead of wearing robes like this, I was wearing other robes. A lot of what I thought about during those two months in Taiwan was, what is the Dharma and what is culture? This is, it’s a delicate thing. Tibetans, in general, do not differentiate between the two. It’s very rare to find a Tibetan teacher who can help you along that line.

We have to think. For example, we once asked His Holiness about, like in the pujas we do tonight, we have the drum and the bell as things that you use to offer music. Now in tantra, the drum and the bell have certain symbolism so that you’re not going to change, but when you are just talking about offering music, His Holiness said you can use a piano, you can use a guitar, it doesn’t really matter because it’s the offering of music that’s important. When making tormas, the Tibetans make the tormas usually out of tsampa, but we don’t have tsampa here. They use butter, it doesn’t work so well here. We usually get a can of something, wrap it pretty, put some decorations on it, and that serves as the torma. It’s a certain kind of offering that you make.

A lot of those external things are what can be changed. The robes change, you can see from one Buddhist tradition to another, the robes change. How you bow changes. How you set up the alter changes. The language you chant in changes, but many of the chants themselves are the same. Not all of them, but many of them are the same. The prayer we do at the very beginning, that one is in the Pali tradition, too. There are certain things you find across traditions.

Then other things, it’s just it’s really cultural. I mean the whole gender thing, in my eyes, is purely cultural, because you think of ancient India at the time of the Buddha. Women were first under the control of their father, then of their husband, then of their son. Is that the way it is here? Forget it. Once you’re a teenage girl, you don’t listen to your mom and dad so much. Sometimes you try, but women are not regarded as property in this society. They were in ancient India.

There are all sorts of things like that, that you have to look at the society in which certain ideas or rituals arose and then see, what’s really the purpose of that and how can we make that in our society? With a lot of the Vinaya precepts we try and look at what the real purpose of the precept is and adapt that, even though maybe we can’t keep the precept letter perfect because the conditions around us don’t support that. It’s very important to be careful in discerning what’s the Dharma and what’s Buddhism, because then you might wind up throwing the Buddha out with the bathwater, which you don’t want to do.

Sometimes when I look around to other Buddhist groups and the kind of adaptations they are making, I have some real questions about if people who are doing this really understand. We also, as Westerners, have a cultural arrogance. There’s still a remnant of a colonialist attitude. There’s still the thing of, “We are more advanced, we can modernize this,” and it’s a kind of arrogance that we have to be very careful of, because unless we understand things deeply, we could make some big boo-boos. I think it’s good to discuss these kinds of things as they come up.

Audience: Also, in regard to the identities that we are talking about and a common worldly issue, the Buddhists have an agenda, our minds have an agenda, and if we’re not our bodies and there is no permanent person and so on, what does it mean to be transgender? Meaning, what does it mean when somebody says, “I have the mind of a man per se, I was born in the wrong body, I am transgender.” How does that work, who is transgender, or what is transgender?

VTC: That’s a very good question. It’s the same question as who is male and who is female? You can see if we talk about masculinity, we talk about femininity, all of this has to do with conceptions, and it’s going to be different in each society. What is considered masculine, feminine, or trans, it’s different in each culture.

Audience: Could it just be that maybe you’ve had multiple lives as a female, let’s say, and you really identified with those qualities, and by the luck of the draw you came in and you had a male body, so you know you’re just kind of…

VTC: It’s a karmic thing. It’s a karmic thing. That’s all I can really say. Why we’re born in the body we’re born into has to do with our karma.

Audience: Even if you’re born and if you identify as transgender, is that an attachment to an identity, or is that a medical condition? I just don’t understand this.

VTC: Let me refer to the sutras. I wonder if they have that in some sutra. I have no idea. What I can say is, anytime we hold anything very tightly, there’s grasping. What made that thought or that identity happen, I have no idea. I can say, whatever we hold tightly is going to be a cause of suffering. You live on North Elliot Street. If you hold, “I am a resident of North Elliot Street, I don’t live on South Elliot Street, I live on North Elliot Street,” that’s going to cause suffering. Why do you live on North Elliot Street? There’s some kind of karma, ask the Buddha that one. I have no idea. No, I don’t understand.

Audience: When we’re meditating and something comes up in your mind that is a deeper reflection or an insight, is it good to dig into that a little bit more or go back to the visualization and the mantra? Not slipping into story or distraction mind, but something you can tell is a more potent insight that should be investigated?

VTC: Something you’re… maybe pieces are falling together in the puzzle and you’re getting some clarity about your past conditioning or why you think the way you do or whatever. They always say virtuous things can be distractions too, but when that kind of thing happens, I always investigate it. I know that if I don’t think about it then it’ll fade and I’ll lose it, and it’s something important that I need to look at, so I look at that.

Audience: I have two questions, and I think the first one’s pretty easy. I just want some clarification about, when we’re doing the visualization and thinking about, for example, the lotus. I don’t normally, but during today’s session I actually started thinking about renunciation, and it became so much more interesting and compelling to do the visualization. At what point… I mean, can we pause for like a minute, five minutes?

VTC: Sure.

Audience: …and build it very slowly and go through the path while we build the visualization.

VTC: Yeah. Right. You can do the sadhana at whatever speed you like. You can zip through it, you can stop and meditate for 10 minutes or an hour, wherever you want to.

Audience: I got a thought like, “Well, the lotus isn’t interesting, but thinking about renunciation is much more engaging.”

VTC: Yeah, it is interesting.

Audience: Thank you. The other question is going back to this thing about purifying before we do an action. I’ve had the experience where I make a determination for a particular amount of time, but I noticed that I have a really strong affliction, and I see myself going towards that action, but I remember I made the determination and give it back.

VTC: You give the determination back?

Audience: Yes. What would you advise? I don’t know how to stop it.

VTC: I just expressed that. I mean, what do you want me to say? You made a determination, then you’re halfway through keeping it and then you really want to do what you said you wouldn’t do, and you still have three days more to go before you can do it so you grit your teeth for three days, and one second after that third day you’re doing it. Or, you still have those three days to go and you just say, “Well, forget it.” If you really feel that the affliction is so strong that you absolutely, positively cannot refrain, then you apologize to the Buddha or whatever, and you purify afterwards, but it’s better not to make a habit of that.

Audience: It’s more about apologizing rather than giving it up? Or, just don’t make that habit.

VTC: That’s it. You got it. Don’t let that happen.

Audience: This is a question about purification, too. I think I understand rejoicing for when I get a boil and things like that, and I realize that it’s karma ripening. Then I have times where I’m really disappointed by not getting something virtuous that I want to do, and I have trouble. Let’s say, go on retreat…

VTC: Oh, and you can’t go on retreat.

Audience: …or get a Dharma book. Or go to a teaching. Then to turn around and rejoice seems confusing.

VTC: What you want to say is, “That’s a result of my own negative karma and my own negative karma is creating that obstacle. I really want to do some purification to free myself from the weight of that karma so I can go to the teaching or do whatever virtuous action it is at a later time.” Don’t throw up your hands and say, “It’s useless, I won’t even try going again.” Don’t do that.

We had a nice Q&A session, no meditation. It’s time to dedicate.

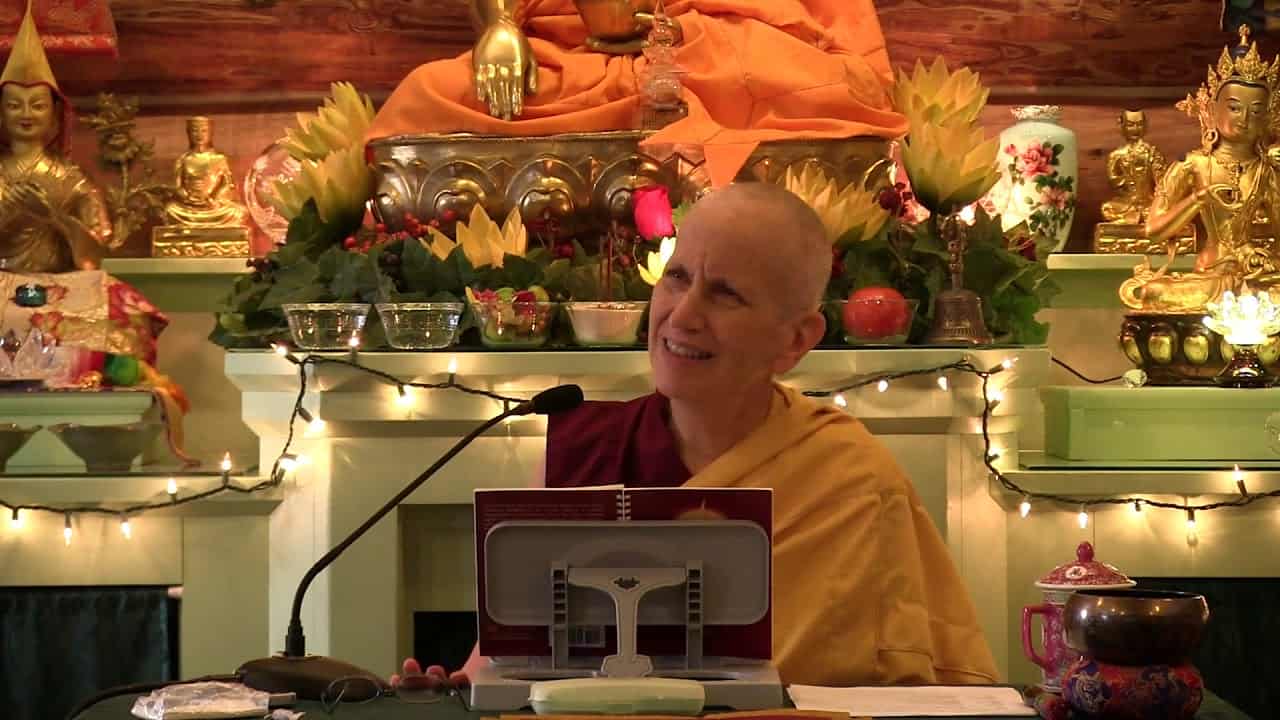

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.