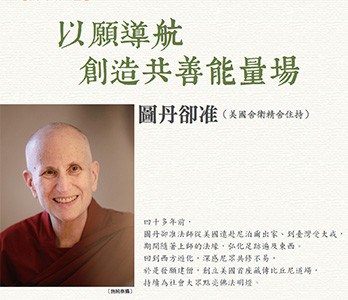

Guided by bodhicitta to create an energy field for common good

This article was originally published in Chinese in Dharma Drum Humanity Magazine as 以願導航 創造共善能量場. (Interview edited by Hezhen Lin, Dharma Drum Humanity Magazine Issue 415)

Interview with Dharma Drum Humanity Magazine (download)

For a long time, I searched for answers about the meaning of life. In 1975, I happened to participate in a meditation course led by two Lamas, and heard them say, “You don’t have to believe anything I say. You should still think about it and put it into practice, to see whether what I have said benefits you.” From then on, I developed an interest in Buddhism.

Download PDF in Chinese.

Traveling afar to the East to ordain and seek the Dharma

At that time, there were few places in America where you could learn the Dharma. I decided to quit my job as an elementary school teacher, traveled afar to Nepal and India to seek the Dharma, and relied upon Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche as my teachers. In 1977, I received the sramaneri ordination from my preceptor Kyabje Ling Rinpoche, who was His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s senior tutor.

As the bhikshuni sangha lineage was no longer extant in the Tibetan tradition, there were a few nuns who went to Taiwan to receive the Triple Platform ordination. Nine years after becoming a sramaneri, I sought help from a Dharma friend, and after receiving permission from His Holiness the Dalai Lama, in 1986 I went to Yuanheng Temple in Taiwan to receive the full ordination, officially becoming a member of the sangha. In my Dharma practice, I rely upon the Tibetan tradition, and in upholding the Vinaya I follow the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya. I often remind myself to be mindful of my comportment, to conduct myself appropriately in order to be in accord with the wishes of my teachers in both lineages.

Living in a different cultural setting gave me the opportunity to observe how American culture had conditioned and influenced my life. When I saw how others did things differently, I would reflect: Is it always good for me to do things according to American custom? Are American values and ways of doing things suitable for other cultures? Is democracy suited to all situations? Thinking in this way helped to expand my perspective, and I learned how to view matters from a range of perspectives.

When I first began to learn the Dharma, many sutras and treatises had yet to be translated into English; we had to rely on oral transmission from our spiritual mentors. I greatly treasured the opportunity to learn from my eminent teachers. When listening to them teach the Dharma, I often felt that what they were describing was their own practice and the experiences they had personally gained from putting the Dharma into practice. I felt fortunate to be able to hear the Dharma from them. My teachers also gave me personal instructions, at times asking me to do things that I didn’t want to do, or to take on tasks that I felt I wasn’t capable of handling. Although their instructions challenged my self-esteem and my abilities, I knew that my spiritual mentors were wise and compassionate, and I had complete trust in them.

A few months after I received sramaneri ordination, my teacher was going to teach a one-month meditation course for Westerners. I was still very new in the sangha community, but I was asked to take on the role of his teaching assistant. I felt that I lacked learning and was unable to take on this responsibility and reported this to my teacher, who looked me in the eye sternly and said, “You’re selfish!” His scolding woke me up, and I mustered the courage to take on the duty of sharing the Dharma.

Propagating the Dharma worldwide according to causes and conditions

Another time, my teacher sent me to a Dharma center in Italy to be the spiritual program coordinator as well as the disciplinarian of the monastic community. Although I was not keen to do this, I followed my teacher’s instruction and learned a lot through being put in this very difficult position. In the past, if my teacher had pointed out that I had problems managing my anger, I would not have taken his words to heart. However, after taking on the position at the Italian Dharma center, I truly saw how easily I got angry. This forced me to learn the Dharma antidotes to counteract anger.

In 1987 I was sent to Singapore to teach and everything seemed to be going smoothly. Then, during a brief period when I returned to America, my teacher suddenly sent me a letter, transferring me to a Dharma center in Australia. This was a major change in my life, yet I had not been asked about my views on it. At that moment I was dumbfounded, disheartened, and perplexed; I wondered, had someone criticized me at the place where I had been assigned a position at that time? For a split second the thought of leaving arose, and that terrified me. Right then I knew that the only thing to do was to let go of my anger, practice thought transformation, and recognize that my emotions are my own responsibility, they are not my teacher’s fault. It was clear to me that when I was unhappy, it was not my teacher’s fault, not the Dharma’s fault, not anyone else’s fault. Rather, my unhappiness was a direct result of my own mental afflictions and the only way out was to practice the Buddha’s teachings.

Due to external conditions at the time, I was unable to take on the assignment in Australia. I wrote a letter to my teacher to explain the reasons, and waited for him to give me a new assignment, but time passed and there was still no news. I had no place to live and so requested him, “May I make my own decision?” He replied that I could. In the subsequent two years, I traveled along like a cloud floating in the sky, as I had no stable source for the four monastic requisites. I could only stay in one layperson’s house after another, and during this time I wrote the two books Open Heart, Clear Mind and Taming the Mind. After returning to Dharamsala for a year to receive teachings, I then returned to America on a Dharma teaching tour.

Transforming adversity into resources for spiritual practice

That was a very difficult time, but I never thought of disrobing. That I was able to persevere came from my understanding of karma: my loneliness and difficulties were not caused by my ordination, but by my untamed mind—it was ignorance and self-centeredness that had caused me to wind up in that situation. Thinking like this was very helpful, because I had no one to take my anger out on, and instead I had to look at the source of my problems. If I didn’t like the result, then I had to stop creating the cause, and that meant practicing the Dharma diligently.

In the Tibetan refugee communities in India and Nepal, lay devotees were often unable to offer material support to foreign monastics. As a result of being unable to support themselves, many Western monastics had no choice but to give up their robes, and return to their countries to work. However, when I ordained I made many resolutions, one of which was never to work for money. The Buddha said that as long as monastics practice sincerely, they will not starve. Even when I was in India, when I didn’t have enough money to buy a return ticket to America and had to be careful not to spend too much on food, I always trusted the Buddha.

Although I am not a very good practitioner, I just try my best and don’t have a motivation that hopes to receive support when I connect with people. I just share the Dharma when there is a request from others. I’m grateful for the kind support I’ve received from many people, and I’ve never gone hungry. Even when I felt lonely, I just had to open my eyes and look around to see that I was surrounded by the kindness of others.

To establish a firm foundation for Dharma practice, it’s essential to let go of—or at least to gradually reduce the eight worldly concerns: attachment to gain and aversion to loss; attachment to a good reputation and aversion to a bad one; attachment to praise and aversion to blame; and attachment to sense pleasure and aversion to what is unpleasant. Although I am currently unable to cut the eight worldly concerns, I reflect on them often, which helps me to relax and not grasp at things. Contemplating the disadvantages of samsara helps to reduce and then let go of expectations that everything should go according to my wishes. I have also come to understand that being criticized or having my reputation ruined is actually beneficial because it helps me to subdue the mind of “I want this, I don’t like that; things should be this way,” and to cultivate humility. In spiritual practice, having a sense of humor is important. Whenever my mind craves for worldly things or people, I make fun of myself, and through this remind myself not to grasp at them.

Aside from this, cultivating love, compassion, and bodhicitta also help to counteract our attachment to “I, me, my, and mine.” Just as Nagarjuna said in his Precious Garland of Advice to a King, “May I bear the results of sentient beings’ negativity, and may they have the results of all my virtue.” This thought-training technique of taking and giving involves visualizing taking others’ suffering into our heart, and by doing so destroying our self-centered mind, and then imagining that we give our body, wealth, merit, virtue, to sentient beings with compassion that wishes them to have happiness and be free from suffering. This process expands our perspective on life and enables us to have a more open heart and to empathize with others’ needs.

Returning to America to establish a monastic community

When I returned to America on a Dharma teaching tour in 1989, I realized that because many people were unfamiliar with Buddhism, they did not understand the purpose of making offerings to monastic communities. Dharma centers were often run by laypeople, and monastics were asked to organize events, and also participate in tasks such as cooking in the kitchen and cleaning rooms. In 1992, Dharma Friendship Foundation invited me to be their resident spiritual teacher. I was the only bhikshuni there and missed the companionship of fellow monastics. The aspiration arose to establish a monastery where Tibetan Buddhist bhikshunis could practice in community.

In 2003, Sravasti Abbey was incorporated and we purchased the land. The only residents were me and two cats, with no organization supporting us. As I sat in my chair wondering how we were going to pay off the mortgage, the cats sat there looking at me, as if to say, “You have to feed us well.” Subsequently at the Western Buddhist Monastic Gathering, I sought advice from elders who had founded monasteries in the West on how to manage a sangha community, and gained a lot of inspiration through that process. Venerable Wu Yin and Venerable Jendy from Luminary International Buddhist Association also gave me a lot of wise advice. Keeping in mind my resolve, and with deep conviction in the support we had from the Buddhas and bodhisattvas, I simply went along with causes and conditions and opened the doors of the Abbey. Gradually, support started to come in, and we even paid off the mortgage in advance.

My students from Dharma Friendship Foundation often came to visit the Abbey. At first, they came to offer help and were merely curious about monastic life, but after a few years, they wished to take ordination. At present, Sravasti Abbey already has 14 resident monastics and one lay trainee. We are the sole training monastery for Tibetan Buddhist bhikshunis in America.

From finding peace within to bringing peace to others and the world

It’s very important for monasteries to exist in society. Personally, when I was a sramaneri, I only focused on my personal spiritual practice. It was only when I became a bhikshuni that I truly understood that the Dharma and Vinaya have been sustained and I could receive the bhikshuni ordination because hundreds of thousands of monastics before me in the past, from the Buddha’s time up to the present, have ordained and passed the lineage down from one generation to the next, thereby preserving the Dharma and the Vinaya. As such I also have responsibility to enable the transmission of the Three Jewels to continue.

In this materialistic world, to have a monastery where a monastic community lives and practices together is like a lighthouse that guides society onto the right path. The presence of monastics inspires individuals and society to reflect: What are our values? What is our responsibility to future generations? Shall we preserve the natural environment for them? Do we really need to wage wars? It’s because monastics give their bodies and minds to their spiritual practice to seek the path to liberation that a layperson once wrote us to say, “Knowing that there are people practicing together in a monastery like you are brings us great comfort and inspiration.” When laypeople encounter difficulties in life, they can seek out the monastic community for help; they can come to practice together with us, listen to teachings, and create virtue. Learning the Dharma and creating virtue alleviates their worry and distress.

For instance, after the US presidential elections in November, 2016, many people felt upset and despondent, and wrote to Sravasti Abbey for help. Some people wondered, “This world is already in such a terrible condition, what can we do? Or is the situation hopeless?” We spent a week giving talks and posting them on the internet to help people view the present situation from a Dharma perspective. Buddhist practice involves growing through difficulties, and not expecting to live in a perfect world, or waiting for great spiritual practitioners to change the world. The situation before us is the ripening of our karma, and we must face and accept it, and then with compassion, act to ameliorate the situation.

When I’m unhappy about the harm some government officials are doing to the country and the world, I chant “Homage to our fundamental teacher, Shakyamuni Buddha,” and bow to all the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. While bowing, I visualize all the politicians whom I disagree with all around me and imagine that I’m leading them to bow to the Buddha together. I hope we’ll make a positive connection in this life, and I dedicate the merit so that in future lives, we may have the opportunity to practice the Buddhadharma and move in a virtuous direction together.

To have the circumstances to practice the Dharma together with other like-minded people in contemporary society is rare and precious. Even though we may admire great spiritual teachers, these great masters do not have the same strong connection to the circumstances around us as we do. If someone needs to exert positive influence on these circumstances, it has to begin with us and our actions.

Think about how the Buddhas and bodhisattvas practiced for countless great eons in order to guide us. They have never given up on a single sentient being. We should learn from their bodhicitta resolve and do our best in difficult circumstances to cultivate compassion and wisdom, thereby creating an “energy field for the common good,” that has the power to bring peace and harmony to society.