Amitabha practice: Dedication verses

Part of a series of short commentaries on the Amitabha sadhana given in preparation for the Amitabha Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2017-2018.

- Meditating on emptiness at various points of the sadhana

- Getting a sense of what it might be like to have the mind and qualities of a buddha

- The power in rejoicing

- The importance of making prayers to meet qualified spiritual mentors in future lives

We’ve been talking about the Amitabha sadhana because it’s going to be our winter retreat practice. We’re just doing the dedication verses today, because we’ve done all the other things before. I have some more topics I want to talk on about this, but I’ll do it after the vinaya program. So for the next few days here I think we’ll use the BBCorners to go into vinaya topics, because people are coming and that’s what they’re here for.

Where we left off yesterday, Amitabha was on top of our head, we’ve done the recitation of mantra and the meditation that went together with that. Then also we did this request prayer for at the time of death. We’re following a sadhana written by Lama Yeshe back in the early 1980s.

Now is the absorption.

The lotus, moon, and sun, as well as Guru Amitabha melt into light and dissolve into my heart center. Guru Amitabha’s mind and my mind become non-dual.

Amitabha on his lotus and moon seat and sun seat on top of our head. He and all of his seats melt into light and then descend through the crown of our head and come to rest in our heart chakra. (Whenever we say “heart” in Buddhism it doesn’t mean the physical heart, it’s not the pledge of allegiance heart. It’s the one that is the heart chakra in the center of our chest.) We imagine that happening, and then we think Guru Amitabha’s mind and my mind become non-dual.

This is another point in the sadhana where you meditate on emptiness, because if you think, what you think of the ultimate nature of Amitabha’s mind and the conventional nature. The ultimate nature is empty of inherent existence, same as our ultimate nature. The emptiness of inherent existence of our mind is our buddha nature. One way to describe buddha nature. And that is when the mind itself gets purified, then that emptiness is called the nature body of a buddha. The emptiness itself doesn’t change, but because the mind that is the basis of the emptiness changes, then the name changes. Before it was the emptiness of a sentient being’s mind. Later it becomes the emptiness of a buddha’s mind.

We reflect on emptiness there—the emptiness of our mind, how it’s the same as the emptiness of Amitabha’s mind—and then we also reflect on the conventional nature of the mind.

Here when it says “Amitabha’s mind and my mind become non-dual,” to think that also the conventional nature becomes like the Buddha’s omniscient mind. When we talk about the dharmakaya of the Buddha…. Referring to the Buddha’s mind, part of it is the nature body, which is the emptiness of inherent existence of the Buddha’s mind, and part is the omniscient mind of the Buddha. We just said before that the ultimate natures are the same (when we think that we’ve become Amitabha), and then here we think our conventional natures are the same (even though they’re not yet, but we think like that because it increases our confidence, and it gives us an idea of what the Buddha’s mind is like), and so at that point when you think “the nature of my conventional mind is like a buddha’s omniscient mind,” then imagine that you have the qualities of a buddha.

That can be quite good for us in terms of changing our self-view. We ordinarily think, “I’m just little old me, I don’t know anything, what can I do? I’m so angry, I’m so afflicted….” But here, if we think, “Okay, I have the qualities of Amitabha’s mind,” then it calls on us to meditate, “What would it be like not to be angry, but to have a mind like the Buddha’s mind that can be very spacious, very tolerant, with a lot of fortitude to undergo difficulties. What would it be like to have a mind that’s not so ego-sensitive, that everything everybody says we take personally? What would it be like to have a mind that is very generous, that isn’t hindered by the kind of miserliness I have now? What would it be like to have a mind that isn’t attached, but sees things in a very spacious, equanimous way?”

This point when Amitabha dissolves into you, there’s actually quite a bit to meditate on here. And some of it really using our imagination of what would it feel like to be like this? And when we can get some sense of what it might feel like, then, of course, we can become like that. But if we never think of what it might feel like, then the idea of quelling our anger just seems totally, “How can I ever do that? It’s impossible.” But if we think, “What would it be like to be a person that doesn’t get angry and isn’t so ego-sensitive?” Then it’s like, “Oh, I can get a sense of that. Oh, it’s possible.” Then when we go back and we apply the antidotes from thought training and lamrim, then those antidotes can really work on our mind in a deeper way.

Very important. It’s not very many words here, but often the parts in sadhanas where there aren’t many words, that’s the point where you need to do the most meditation.

It says,

Rest the mind in the experience of being non-dual with Guru Amitabha’s realizations.

Now, this particular sadhana doesn’t have a self-generation practice. It goes right to the dedication verses. The first two dedication verses are the standard ones that we do.

Due to this merit may we soon

Attain the awakened state of Amitabha

That we may be able to liberate

All sentient beings from their sufferings.

This is matching our dedication to our motivation. The motivation of our practice was to do this in order to become a buddha to be of the greatest benefit to sentient beings, and here we are dedicating for the purpose that we motivated by. It’s bookends, really holding the practice together.

And then,

May the precious bodhi mind

Not yet born arise and grow.

May that born have no decline

But increase forever more.

Really dedicating so that our bodhicitta doesn’t decline, and remains and increases. Again, very very important.

Here it says “bodhicitta.” It technically could refer to conventional bodhicitta, the aspiration for full awakening for the benefit of sentient beings. Or it could refer to the ultimate bodhicitta, just when they say bodhicitta. But here it’s mostly meaning the conventional one, because often they add another verse…. “May the precious wisdom realizing emptiness not yet born arise and grow, may that born have no decline but increase forevermore.” We can add that in there, too.

Due to the merit accumulated by myself and others in the past, present, and future,

That’s a lot of merit. This is also rejoicing. It’s not just the practice of generosity, dedicating our merits for others, but it’s the practice of rejoicing at the merit we created and at the merit others created.

Rejoicing is a very important practice, as we all know. It’s the antidote to jealousy. And actually I think here when we rejoice in our own and others’ merit, it’s also the antidote to the kind of despair that people feel in the world today. Because so often people, especially in the age of Trump, (not all of you are Americans, but he influences everybody now….) You go “oh no, what’s happening? We thought 1968 was bad…. But this is too much…. What’s going on now, and how do we even deal with it?” That mind is just looking at what we think is wrong. It’s not recognizing how much goodness there is in the world. So to rejoice at our own merit is important, to rejoice at others’ merit, in other words there’s goodness that other people create. We don’t have to think here of just Dharma practitioners. Of course we rejoice in the merit of the buddhas and bodhisattvas, because that’s tremendous merit to rejoice in, but let’s also rejoice in even the small merit of the sentient beings. Whenever somebody in the congress does something that’s the least bit charitable, we should rejoice. Shouldn’t we? So if they pass this program for the children’s health insurance program, if they can pass that, let’s rejoice. Okay, there’s a lot of other stuff going on, but okay, here’s some goodness we’re taking care of kids’ health. It’s important to rejoice at that. There are so many people being active in this day and age, not just politically active, but socially active, really reaching out and benefiting others and doing all sorts of projects.

I was really heartened yesterday. The Youth Emergency Services of Pend Oreille County that Venerable Jigme and I were on the board there, the Kalispel Tribe asked us to partner with them in doing a whole program about preventing violence against women. It includes domestic violence, date rape, all these kinds of things, and doing that kind of program. So here are a bunch of people, and Pend Oreille County, they know nothing about Buddhism. But they want to do something that prevents violence and helps half of the world’s population. Fantastic. Let’s rejoice. And there are tons of people all around the world who are doing these things. It doesn’t have to be done through an organization. It’s nice if you volunteer with an organization. But there are so many people doing kind things for other people that people don’t even notice. You take care of sick relatives, you take care of the elderly, you take care of children. You don’t get paid, but look at the kind of virtue you create by being of benefit to sentient beings. So we should rejoice in all of this, and train our mind to look at what is going well.

This is the merit of ourselves and others in the past, present, and future. Big merit.

Then we say,

…may anyone who merely sees, hears, remembers, touches or talks to me be freed in that very instant from all sufferings and abide in happiness forever.

This is one of the prayers of bodhisattvas. We always say bodhisattvas make prayers that can’t possibly happen, but just the process of making those prayers and aspirations enhances the mind. This is one of them. Many people hear the name of the Buddha but in that very instant they’re not freed from all sufferings and abide in happiness forever, but the Buddha sure made this aspiration. And many people who do hear the name of the Buddha go, “Oh, what’s that about?” Maybe they aren’t liberated from everything forever, but they go, “Oh, who’s the Buddha? What’s going on? Maybe I should learn something about this.”

Last Saturday we had a junior in high school from our local high school who heard about the Abbey from a friend of his in Sandpoint who came here, and he came. Sixteen years old. He came to the Abbey. He heard Abbey. Buddhism Didn’t know anything about that. What’s going on? It sounds interesting. This kid, sixteen years old, first Dharma teaching he walks into. What was I talking about? About Amitabha’s pure land. What were we chanting that day? It was the four mindfulness practice in tantra. Do you know the imprint that was put on this kid’s mind? And he just came out of curiosity because he heard the name Buddha. So there are potent things that can happen.

Now, often, when people hear my name, I don’t think they get that inspired that they want to go find out. Sometimes people hear my name and they go, “Where is she? I’m going as far away as I can. Oh that person? I heard about her, no thank you.” But imagine just slowly training ourselves and developing our good qualities so that slowly, maybe some people when they hear our name they’ll get inspired. I’m often confused with Pema Chodron. People often write to me “Oh I loved your book so much. You’re book ‘When Things Fall Apart’ was fantastic!” So I reap the benefit of having the same name as she does. Then I have to write back and say, “Sorry, that’s not me, that’s Pema Chodron, I’m Thubten Chodron…. Look her up, not me…” [laughter] But it would be nice, at some point, so that if people heard our name they would feel inspired. So we start out with making that kind of aspiration.

In all rebirths, may I and all sentient beings be born in a good family,

Here “good family” means born as a bodhisattva. I think it’s also good to pray that we’re born in a Buddhist family where we can be introduced to the Dharma when we’re kids, and where our parents encourage us in practice. Although I was born in a family that’s as far away from a Buddhist family as you can get, and still I really appreciate the family I was born into, because…. You could look at that as a bunch of hindrances, or you could look at it as, “Wow, I had a lot of space.” And I was very fortunate, and I really appreciate the upbringing I got. So there are many ways to talk about what “good family” is. It depends on what your mind is.

…have clear wisdom and great compassion, be free of pride….

Really? Do I have to be free of pride? Can’t I have a little bit of arrogance? Because after all, I am better than all these other people. Yes? Especially, I’m a sangha member, I’m better than these lay people. Look at them. I wear these robes. They should respect me.

But then, when we look at the teachers we respect the most–or at least that I respect the most–they are the ones who are the most humble. You look at His Holiness, he says, “I don’t present myself as a teacher, I just think that I’m sharing what I know with brothers and sisters.” So if His Holiness sees himself that way, shouldn’t we as well? That’s one of the biggest ways to turn people off of the Dharma is if we’re arrogant.

…and devoted to our spiritual mentors,

First of all, I think in here, to pray, to dedicate that we meet fully qualified Mahayana and Vajrayana spiritual mentors. that’s number one. That we meet fully qualified teachers. We don’t meet Charlatananda. We meet really good teachers. And second of all, when it says “be devoted,” may I recognize the qualities of my spiritual teachers. May I admire their qualities. May I follow their instructions. If I don’t understand their instructions, may I go and ask them questions so that I understand what they’re getting at. May I treat my teachers with respect, not just as people who are going to give me what I want. “I want ordination. Come on. I want teachings. Come on.” Our teachers are not our servants that we demand things of, but whom we approach with an attitude of humility, and really seeing their qualities, because they’re the role models that we want to emulate.

…and abide within the vows and commitments to our spiritual mentors.

This is whatever precepts we’ve taken—pratimoksha precepts, bodhisattva precepts, tantric precepts—whatever commitments we’ve made, if we’ve taken empowerments or jenangs, may we abide with these, may we keep them and value them and treasure them, and make them the heart of our lives.

It’s important to dedicate this way, because I look at, for myself, when I met the Dharma I was 24. Super naive. Super innocent. Had I met Charlatananda who knows what I would have done? But by some amazing karma I didn’t meet Charlatananda, I met my teachers. And I met these excellent, fantastic teachers that you can’t find anything better than that. How did somebody like me, growing up the way I did, and being so completely naive, have the good fortune to meet the teachers I did? The only thing I can trace it to is I must have made–whoever I was in a previous life, some caterpillar–made really good dedication prayers. So I think it’s important to make these kinds of dedication prayers so that our karma ripens that way in the future, and to start practicing the meaning of those prayers here in this life, too. It’s not “in future lives may I be humble and meet good teachers,” but in this life may I be humble and also check out and meet good teachers.

By the force of these praises and requests made to you, may all disease, poverty, fighting, and quarrels be calmed. May the Dharma and all auspiciousness increase throughout the worlds and directions where I and all others dwell.

I don’t think that needs much explanation. But that comes from our heart, that’s our wish, isn’t it? What we all want.

That completes the words of the sadhana, but like I said, I’m going to go back afterwards and go more into how to meditate on Amitabha, because there’s quite a lot in there that we can do.

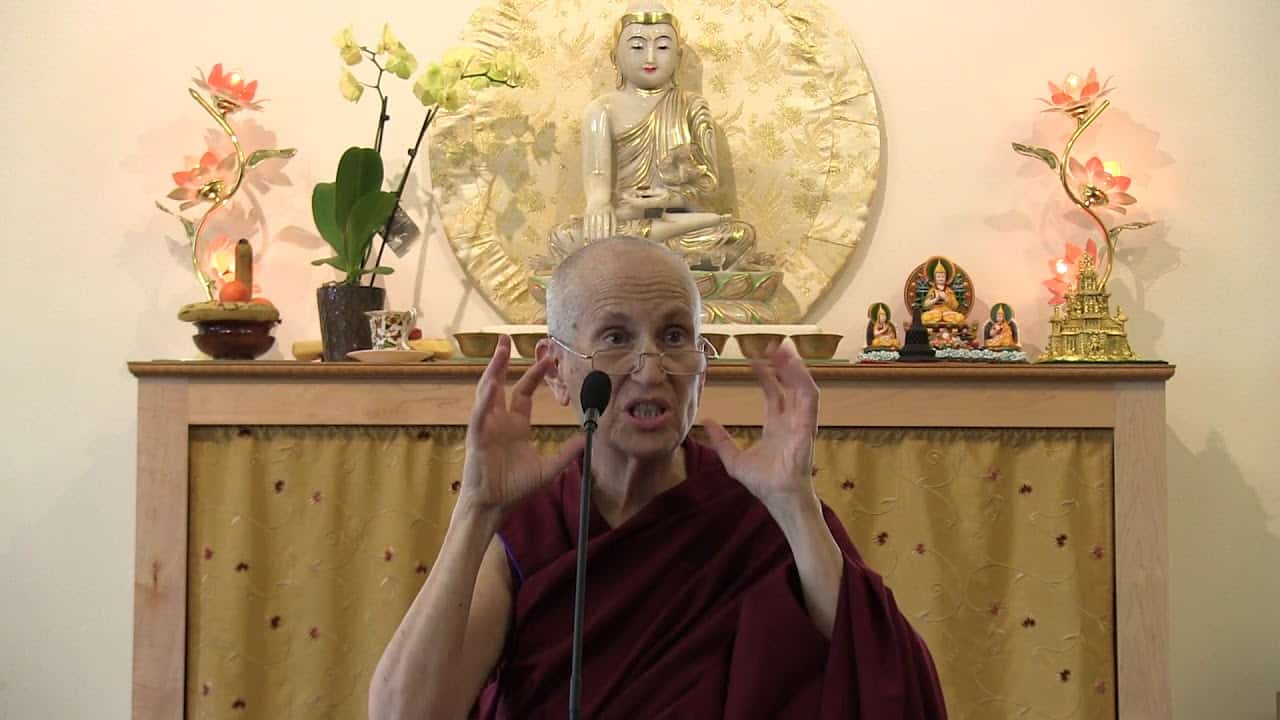

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.