The love of money

A three-part commentary on a New York Times op-ed article by Arthur Brooks entitled "Love People, Not Pleasure."

- Money and material possessions are how many people measure success in society

- People who rate materialistic goals very highly are in general more anxious and depressed

- It is better to want what you have than to have what you want

The love of money (download)

Part 1: Love people, not pleasure

Part 3: The formula for happiness

I wanted to continue sharing my thoughts on this op-ed article by Arthur Brooks called “Love People, Not Pleasure” that we started yesterday.

Yesterday he was talking about happiness and unhappiness, and went through how people think fame is going to bring you happiness and how you become a junkie, always needing more and more fame but it never really satisfies you and fills you up.

Now he’s going to go on to talking about material things. So he says:

Some look for relief from unhappiness in money and material things.

This is one of the prime things in our society, isn’t it? And it’s very often how we measure success in our society. If you have money and if you have material things.

This scenario is a little more complicated than fame.

Actually, I don’t agree with that. I think the attachment to reputation is much deeper than the attachment to material things. And they even say that for Dharma practitioners; somebody can very easily give up food and things like that, and go up to a solitary hermitage and do retreat, but while they’re in retreat they’re thinking about, “Oh, all the people in the city know that I’m up here doing retreat and they know that I’m a great practitioner.” So that even though somebody may renounce material things–somebody who just did a year-long retreat is nodding her head in agreement with this–that the mind has a very difficult time freeing itself from what other people think. So this is what this guy thinks.

The evidence does suggest that money relieves suffering in cases of true material need. (This is a strong argument, in my view, for many safety-net policies for the indigent.) But when money becomes an end in itself, it can bring misery, too.

Buddha taught this! [Laughter]

For decades, psychologists have been compiling a vast literature on the relationships between different aspirations and well-being. Whether they examine young adults or people of all ages, the bulk of the studies point toward the same important conclusion: People who rate materialistic goals like wealth as top personal priorities are significantly likelier to be more anxious, more depressed and more frequent drug users, and even to have more physical ailments than those who set their sights on more intrinsic values.

That’s interesting that they’ve done research and found that. Because remember intrinsic values are like your personal values and what’s important to you and connecting to other people and how you want to grow as a person, these kinds of things that can’t be measured by society. And here all the things that can–especially money, I mean that’s the easiest to measure by society–then the people who are hooked the most on that–more anxiety, less likely to be happy, more physical ailments. And you can see why, because for them…

I think this actually links in to fame, too, because when you’re attached to material things it’s not just the material things are making you happy. I mean, up to a certain point, because when your basic physical needs are met, up until that point, yes, those material things to bring you happiness. But above that point, why do people consistently need more and better, more and better? My observation is, one, they’re trying to prove to themselves that they’re worthwhile human beings, because this was the family value they grew up with was that success is measured by money and material things. So they’ve internalized that value, and in order to feel like they’re successful human beings they need to have this stuff, for their own self-worth. The other thing is, I think, that because having money and wealth also gets you fame. Also gets you power. If you’re written up in Fortune 500, then you’re not only rich but you’re famous. And if other people know that you are rich, and wealth is the sign of success, then other people know you’re successful. So you get the fame of being successful. And then that also, you use that as a way of trying to feel worthwhile as a human being. If I have money society says that I’m successful then I can feel I’m successful then I’m worthwhile. So I think it isn’t just the money and material things. I think it’s what the money and possessions represent in society. That’s the real hooker here. He doesn’t go into that. Maybe he doesn’t see it. But anyway…

No one sums up the moral snares of materialism more famously than St. Paul in his First Letter to Timothy: “For the love of money is the root of all evil: which while some coveted after, they have erred from the faith, and pierced themselves through with many sorrows.”

Here when he says “the love of money is the root of all evil,” this is also often quoted as “money is the root of all evil.” It’s not. It’s the love or attachment for money, because that attachment … In EML we did one discussion session on money and how many different things money can symbolize and represent for people. So it’s the attachment to all those things that makes people lose themselves, and lose their values. And then this author continues:

Or as the Dalai Lama pithily suggests, it is better to want what you have than to have what you want.

And that’s the whole idea behind contentment. To want what you have. Not to focus on having what you want. Because when we focus on having what we want we live in a state of dissatisfaction. And our wants are unlimited so there’s no way to satisfy it. Whereas if we want what we have and we’re content with what we have, no matter how much we have we’re at peace in our hearts.

Tomorrow we’ll start on sense pleasure. That’s the third thing that he was talking about, what people use to feel like good people. Or to get happiness.

Part 1: Love people, not pleasure

Part 3: The formula for happiness

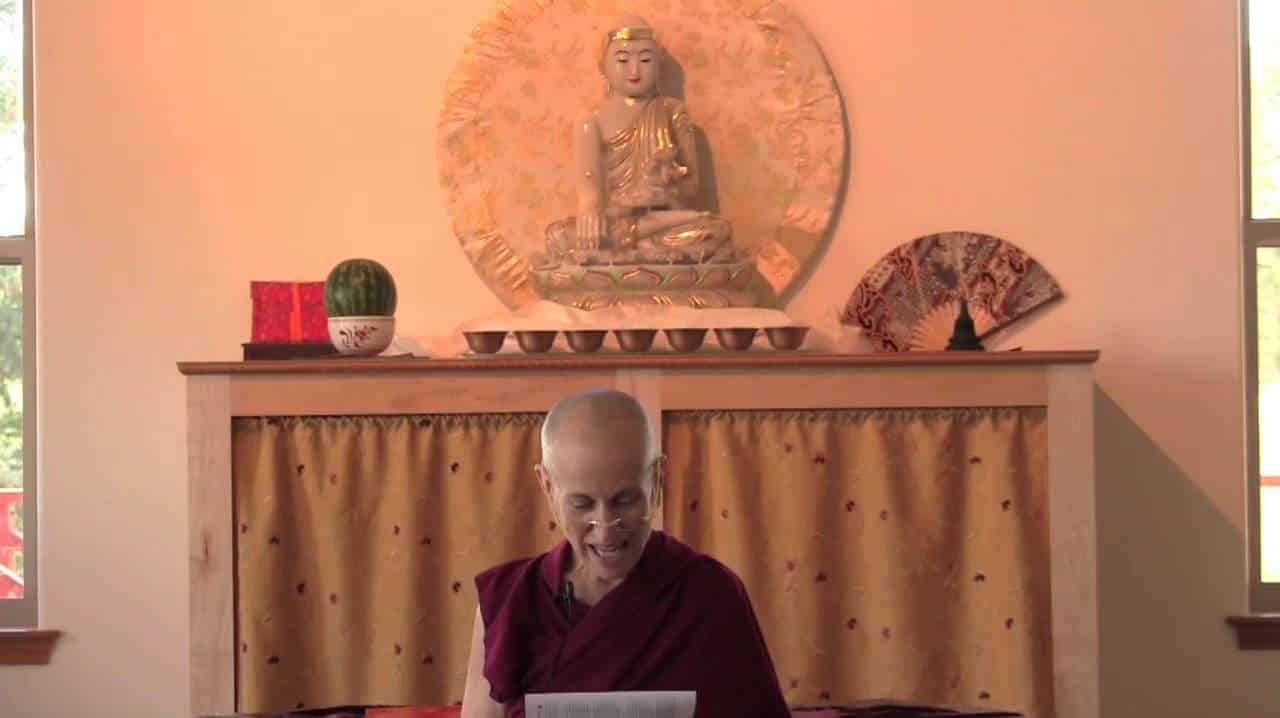

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.