Sixteen attributes of the four noble truths

Part of a series of teachings given during the Four Noble Truths Retreat, July 18-20, 2014.

- Remaining three aspects of true dukkha

- Three kinds of dukkha that the body and mind experience

- Each one of us has the potential to change how we think

- Aspects of true origins: craving and karma

- Aspects of true cessation: ceasing of afflictions, peace

- Aspects of true paths: wisdom realizing selflessness, awareness

Yesterday, we started talking specifically about the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths, and I was mentioning that each aspect counteracts a wrong conception. There are four wrong conceptions about each of the four truths. You’ll also recall that yesterday we were talking about true suffering, or true duhkha, that included four things: the aggregates, the body, the mind, the environment, and then the resources.

Four wrong conceptions

We have four misconceptions regarding each of these four truths. The first wrong conception we talked about yesterday is thinking the four noble truths are permanent. We talked a lot about thinking that our body was permanent and not aging—not going towards death—and also thinking that our environment, our resources, the things we use, are also permanent and unchanging. That’s why we’re surprised when they change, and we are kind of shocked and wonder how that could happen.

I’ll just read the sentence that encapsulates it:

Phenomena such as the physical and mental aggregates are impermanent.

Why? Because they undergo continuous, momentary arising and disintegration. They’re changing moment by moment. Arising and disintegration.

The second misconception is believing that the aggregates are satisfactory. The second refutation:

The aggregates are unsatisfactory in nature.

In other words, they are duhkha in nature because they’re under the control of afflictions and karma. When we say afflictions, it includes ignorance. Sometimes I point out ignorance specifically by saying ignorance, afflictions, and karma, but actually ignorance is an affliction.

The aggregates, especially our body and mind, are unsatisfactory because they are subject to three different types of duhkha—three different ways in which they are unsatisfactory. I’ll just list those and then I’ll explain them: the duhkha of pain, then the duhkha of change, and the pervasive, conditioned duhkha.

The three types of duhkha

The duhkha of pain refers to gross pain that any living being, no matter what realm they’re born into, sees as pain. This might be physical pain or mental pain. We have lots of experience with those, right? And no one likes them; everybody wants to get rid of them. We don’t always know the skillful way to get rid of them, and sometimes in trying to get rid of them we make them worse. Everybody sees that as something unsatisfactory. The other two types of duhkha are more difficult to see as unsatisfactory, but when we think about them, we will.

The second type is the duhkha of change, and this is the fact that nothing in its very nature is pleasurable. Even what we call pleasure is labeled in dependence upon a very small discomfort. The famous example is that you’re sitting down and your back and your knees hurt. You want to get up and stand. That’s the duhkha of pain. When you first get up and stand you say, “Oh, that feels good.” At that point, we call that pleasure. But if standing—in and of itself—were pleasurable, the longer we stood up the happier we would be. But what happens? The longer you stand up, you think, “I want to sit down. I’m tired. I’m exhausted.”

The pleasure that we felt at the beginning of standing up was actually the small discomfort from standing. As we stood longer and longer, that small discomfort grew bigger and bigger. As it grew bigger and bigger, then we started calling it pain even though it was the same continuity of that original feeling of pleasure. What this one really accentuates is that even what we think is pleasure, by its very nature is not pleasurable, because if we do it long enough we want to get away. It becomes painful. This also emphasizes the point that anything external that we get is unable to give us any kind of lasting happiness or lasting security. Why? Because it changes into something uncomfortable as time goes on.

If you think of some kind of happiness you’ve had in your life—imagine the highest happiness you’ve had so far in this life—and imagine being with that person, or doing that activity, or being at that place for one month straight with no break or doing anything else. Let’s say it’s lying on the beach with this person you’re madly in love with: there you are, lying on the beach with this person you’re madly in love with for one solid month. You don’t go and do anything else. If this were true happiness, the longer you lay on the beach with this person, the happier you would become.

Do you think you could make it a whole month lying on the beach next to them with no break? You’ve got to be with them all the time and be on that beach all the time. Let’s say you could even make the sunshine permanent. You’re in the sun 24/7 for a month. That should be the ultimate happiness because you have everything you want for a month, but that doesn’t sound very enjoyable, does it?

Audience: Do we conclude that true happiness is maintaining a constant state of change before we took over?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): That’s the conclusion you draw when you can only think of the happiness of this life. When we only think of the happiness of this life then that’s true. Then we have to do everything up until the exact moment where it starts to get obviously painful, and then we suddenly switch activities and hope that the person we’re with and the environment and everything else wants to switch at the same exact moment that we do. [laughter]

That’s what we’ve tried up until now. We think, “Honey, I’m too hot in the sun; can we go in?” “No, I’m just beginning to get tan.” “I’m burning; can we go in?” “No, I want to go swimming again.” Whatever it is—are you going to be able to set it up exactly? No. Or you land the perfect job. Do you think you’re going to have pleasure at this job for exactly eight hours every day? [laughter] Well, nowadays it’s more like ten. So, for exactly ten hours every day you’re going to be happy. Do you think you’ll have no bad days and that job is going to bring you everlasting happiness?

Samsara is unsatisfactory

This is why we say samsara is unsatisfactory in nature. Nirvana, on the other hand, is not under the influence of afflictions and karma. Nirvana—which is the cessation of duhkha and the origins of duhkha—is able to give us lasting peace and happiness because it’s not dependent on external things. It’s not dependent on our very fickle, changing mind. Because our mind really plays a big element in all this unsatisfactoriness and being fed up with something, doesn’t it?

One day we think, “Oh, this is marvelous. Venerable Yeshe’s chocolate chip cookies are wonderful!” And then you eat them for a week. Uhhh. [laughter] External things are not going to do it for us. The kind of happiness that comes through Dharma practice is an internal kind of happiness that doesn’t rely on getting the external things we want, or getting away from the external things we don’t want. This kind of happiness—the happiness that comes through eliminating the afflictions and the karma that causes rebirth—is a much more stable kind of happiness because it’s something internal that isn’t fluctuating according to the winds of karma.

Right now, we don’t have a lot of experience with that internal happiness, but as we practice more and more, we begin to see, “Oh, if I change my mind I can be happy; if I don’t change my mind, I’m not going to be happy.” Have you ever been in the most beautiful external situation where everything’s exactly as you want it, and you’re miserable? There you are on the beach with the perfect person, and you just had a fight. Or maybe you didn’t have a fight, but you’re feeling blah—uncontrollably blah. Are there some days when you just feel blah?

So, there you are in the situation where you should be thinking, “Wow!” But you are writing on your Facebook instead of experiencing the happiness. You’re telling everybody how happy you are and taking a selfie so you later can experience this time because you never experienced it in the moment because you were too busy writing about it and taking pictures of it. You begin to see that if we change the mind then we can be happy anywhere.

Sometimes you meet people who have been through extraordinarily difficult events in their life, and they’re fine. They’re fine. They’re not freaked out. They’re not bummed out. They’re not hysterical. They’re not depressed. They’ve been through difficulty, but because they’ve been able to work with the inner mind, they can manage during these difficult situations. Whereas if we don’t have a strong practice, then even the slightest bit of discomfort and we just crumble. We can’t stand it. True or not true?

When the afflictions are overpowering, and our Dharma practice is very weak, then the slightest little thing gets us totally bummed out—for a long time, sometimes. Whereas when we have a strong practice, we go through the internal transformation, then the external situation is not experienced as so awful. And people can actually grow during those difficulties. This is why Dharma practice is important, because without it, we just fall back on all of our old habits. And, phew, I don’t know about your old habits, but my old habits aren’t any fun.

Pervasive conditioning duhkha

The third misconception is pervasive conditioning duhkha or you could say conditioned duhkha. It’s both; it conditions and it is conditioned. This refers to just having the five aggregates that we have: a body and mind under the influence of afflictions and karma. Just having that is an unsatisfactory state. Even when we’re not experiencing gross misery at this particular time, we are walking on the edge of a cliff, and with the slightest change of condition, plunk, we go over.

You may have experienced this in your own life where everything is great in your life, and then someone gets in a car accident. “That wasn’t supposed to happen. That wasn’t on my life plan. It wasn’t on my agenda today. That kind of thing happens to other people, not to me.” And plunk—you go over the cliff into outright suffering. But even before the car accident, when you thought you were happy, that happiness wasn’t secure happiness because our body and mind are still under the influence of afflictions and karma. So, you’re walking right on the edge of that cliff.

As long as the good karma is ripening, we are on top of the cliff. As soon as there is some change in circumstance—boing—we go into obvious pain. We say that that state of just having a body and mind that are susceptible to pain is unsatisfactory. So, those are the three kinds of things being unsatisfactory.

How do we deal with these things? You could say, “I’m so depressed. Everything’s unsatisfactory. There is pain. My happiness goes away. My whole situation sucks because I have a body and mind. Woe is me! This is terrible. I’m just going to lock myself in my room and eat cookies all day or drink all day or smoke all day or read novels all day”—whatever it is you take refuge in when you’re unhappy. And that doesn’t work because you’re still depressed.

Do you think that’s the mental state the Buddha is trying to cultivate in us by teaching this? I hope you say “No.” [laughter] If you say “Yes,” then I haven’t explained it very well. That’s clearly not the state that the Buddha is trying to encourage in us. Why is the Buddha pointing this out? Because all of these big problems are caused by afflictions and karma. Afflictions and karma are rooted in ignorance, and ignorance can be eliminated. There exists a state of peace beyond all these unsatisfactory conditions. There is a path to follow to get us to that state of peace. And the Buddha’s saying, “Hey, you’re in prison. The door’s over there. Instead of banging your head on the prison wall, go out the door.”

Motivation for changing our minds

Mitch just wrote me a beautiful story. Do you want to tell this story?

Audience: We arrived on Thursday, and I was nervous. I didn’t know about the check-in procedure. I started walking to try to check-in on time. I see this little bird in the barn flying against the window, over and over. I’ve never seen a golden bird like this. But I was late coming in, so I was torn. I didn’t know how to get into the barn. I abandon all concern and go to try to save the bird. I think I’m opening the sliding window. It’s banging its head against the window, freaked out. I’m trying to move the window, and the window doesn’t open. Finally, I push it and the bird wakes up and flies out the huge garage door open the other way. [laughter] And I realized it wasn’t a bird; it was a bodhisattva teaching me to stop banging my head against the same wall all the time. “Turn around. Stop. There is a big open door.”

VTC: There is the big open door—turn around and fly out of it. That’s what the Buddha is trying to teach us by explaining the second quality of true duhkha. There is a big open garage door. Fly out—stop banging yourself against the window.

By explaining this, the Buddha is trying to help us generate a strong motivation for liberation. In the meantime, from now until we attain liberation from all these states of duhkha, the more aware we are of how our own mind plays an active part in our experiences of pain, the more it gives us a choice in situations to think in another way, to view the situation in another way, to stop our immediate suffering. So, even if it’s going to take us a while to eliminate all ignorance and get out of cyclic existence, still, if we can realize at any particular moment that “I have the potential and the opportunity to change how I’m thinking. And if I do it, this situation of discomfort or pain or suffering can change accordingly.”

That gives us a lot of power in our lives, just by changing our minds. We have to remember that. When we’re sitting here, we think, “Oh yeah, change my mind,” and as soon as somebody does something we don’t like, we forget that. And instead of saying, “Oh, I can change my mind,” we say, “Something’s wrong with the world. Something’s wrong with me. Everything’s horrible.” And we go back into our hole with the rockets shooting out of it.

We have to remember this no matter what’s going on. And this is why lamrim teachings on the stages of the path are so important and why the lojong, or thought training, teachings are so important, because if we learn these teachings and we do the lamrim and thought training meditations, then when we face difficulties we are already familiar with the methods to practice to change our perspective, to change our mind. If we don’t do these meditations on a day-to-day basis, then when we have a problem we don’t know what to do. Then you ask somebody, “What do I do?” and they tell you. Because you haven’t developed familiarity with these methods by thinking about them very often in your daily practice, then at that time you’re trying to use them, they feel uncomfortable because you’re not well habituated.

The real trick is to learn these methods and then practice them in a consistent way. And when you do, when you need them they’re right there. And also, as you practice them your view changes completely so that you stop interpreting things in the same, old rotten, self-centered way. Because you’re practicing seeing things in a different perspective.

There is a lot going on with my birth family. This is my family here at Sravasti Abbey; this is my home. But with my physical family, there is a lot going on. My father just died and other stuff is happening. There was one day and several emotional outbursts, and I was really surprised. I sat there and I just watched. My understanding was that these people are stressed. These people are in pain, and they’re stressed. That’s why they’re doing this. I didn’t take any of what was said to me or what was going on in a personal way.

Whereas, years ago, if you just looked at me cross-eyed I would crumble. So, I thought, “Oh, okay, something in my practice must be working because I didn’t react in the same way.” It’s not that I enjoyed the situation—the whole thing was really quite sad and unnecessary—but I realized they are simply stressed. How much do they mean what they say? I have no idea. And it doesn’t really matter if they mean what they say. It doesn’t really matter because they’re just stressed right now. And the situation hasn’t ended either. You should read my email this weekend. Maybe you shouldn’t read my email. [laugher]

The third wrong conception

The third wrong conception is that painful things are pleasurable. The way out of it is to realize that, “No, duhkha is duhkha.” And we can mitigate it now by practicing the Dharma, and we can escape from this situation forever through really deepening our practice. The third misconception is that the aggregates are attractive, beautiful and desirable.

We usually focus on the body, but it could include the mental aggregates as well. But we start off really focusing on the body. In our everyday mind there is this whole idea of thinking the body is beautiful, the body is desirable, the body is a source of pleasure, and it’s attractive. Especially in our society now, there is so much emphasis on the body and on pleasure from the body and the beauty of the body. And we use sex to sell everything. How you use sex to sell laundry soap is beyond me, but they’ve invented a way to do it.

This is all manipulating our mind and creating more desire. It’s based on this view we have that our body is really something far out and other people’s bodies are really something terrific. There is that good-looking person who walked in the room, and, “Wow! Where is he doing walking meditation? I want to do my walking meditation nearby. [laughter] We’ll bump into each other.”

But what is the body, really? Is the body really attractive? [laughter] It’s very true. As long as you don’t think about it, the body is attractive. As soon as you think about it, it changes. What is inside the body? There is all kinds of nice stuff inside the body. Some people, they look at the inside of the body and they faint. They’re horrified. It’s so atrocious. Here we are with this body that actually is rather foul by nature but that we think is just gorgeous. Then you’re going to say, “Well, some parts of the body are nice, like the skin, the hair, the eyes.” What do people say? “Your eyes are like diamonds and your teeth are like pearls?” I don’t know—whatever it is. [laughter]

Let’s say you take the person’s body apart, and you put their eyes there. And you lay out their teeth here, and you put their hair over there. And you spread the skin across here. Those same body parts, are they gorgeous now? With the airplane crash in the rebel-held area of Ukraine, it’s three days later, and they’re just beginning to take some of the bodies out. Can you imagine what those bodies look like after three days in the summer heat? Can you imagine what they smell like after three days in the summer heat? When the people got on the plane, they’re all looking nice and they’re attractive. Their hair is combed. Everything’s beautiful. And now? Some of the bodies are intact—bloated, smelly. Other ones are in different pieces. Are the pieces of the body beautiful? Not so. Not so.

There’s some kind of distortion in our way of seeing things, isn’t there, that we think that this body is so beautiful and such a source of pleasure? It’s not so beautiful. At the end of the day the body is the real thing that betrays us.

Audience: How do you stop from going in the opposite direction that you hate your body, and you want to hurt yourself?

VTC: How do you keep from going to the other extreme that you hate your body and you hurt it and so on? First of all, the body is not inherently beautiful, but it’s also not inherently atrocious either. But moreover—and most importantly—in this lifetime our body is the basis of our precious human life. This body is the basis upon which we can practice the Dharma. So, it’s extremely important that we take care of our body. It’s important that we keep our body clean, that we keep our body healthy. It’s not an issue of hating our body. There is nothing to hate in the body. It’s just a matter of being realistic about the body.

When we’re at this extreme of overestimating the body, then we want to get to the middle point of thinking, “Okay, I have a body. It’s not going to be the source of my everlasting pleasure. It’s really kind of yucky. Everything that comes out of this body is yucky. And everything that comes out of other people’s bodies is likewise yucky. So, I’m not going to sit there and swoon over other people’s bodies because who wants a pile of yuck?”

However, this body is the basis of my precious human life and, in that way, it’s extremely valuable. I need to take care of my body and use it wisely so that I can practice the path. Then when you have this view, you really take care of your body in a healthy way. You start eating better. Instead of eating junk food, you eat well because you realize, “If I eat junk food, and if I’m overweight and get diabetes, I’m going to shorten my own lifespan and that is detrimentally going to affect my Dharma practice. My Dharma practice is the most important thing in my life, so I need to keep my body fit, at the right weight, and eat healthy food.” And so we go about doing that. That’s not torturing the body, is it? The Buddha was very much against these extreme ascetic practices because that doesn’t help.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: I’m not saying should and shouldn’t. I’m just explaining the teachings and then people can understand them as they wish and apply them in their own lives as they wish.

The aggregates are empty

The third quality of true duhkha is that the aggregates are empty because they are not a permanent, unitary, and independent self. Now you’re going to wonder, “Wait a minute, how does that go against this idea of the body as foul? How does that counteract that?” It isn’t initially obvious. The distorted conception is thinking it’s pure. So, how do we counteract thinking that it’s pure and realize that it’s actually foul?

This mistaken belief that the foul body is something pure and clean is related to holding the person and the aggregates to be separate entities. In the Buddha’s time, people very strongly adhered to the caste system whereby the people in the higher caste thought their bodies were pure. And they thought the people in the lower castes had foul bodies. That’s why they wouldn’t touch them and they wouldn’t come in contact with them. It was kind of like racism in America except it was casteism. But this whole idea that somebody else’s body is foul whereas my body is pure, that’s a big misconception, isn’t it? All bodies are made out of the same elements. They all have livers and intestines and goo inside. It’s not that my goo is pure and your goo isn’t. It’s all equally foul.

The higher classes, the Brahmins, who thought that their bodies were pure, back this up by a philosophical belief that everybody had an atman, or a soul, that was independent, unitary, and permanent. It’s usually permanent, unitary and independent. Independent here means not depending on causes and conditions. And so, since the atman was permanent, they said, “Well, we of the highest classes have permanent atmans that are higher, and better, and purer than the lower caste atmans who have these foul bodies. Our bodies are pure. Our atmans are pure. Yours are not pure. And since our atman is permanent, you can never become pure, and I can never become impure. And all my kids are pure by birth.”

So, they established this whole rotten social system based on this wrong philosophy, based on our wrong conception that the body is pure. The Buddha, by saying, “Hey, wait a minute, there is no atman that is permanent, unitary, and independent,” completely shattered the basic philosophy for the caste system. And so, in that way, we say that this third understanding that “the aggregates are not a permanent, unitary, independent person” counteracts the third misconception of the body being pure. It makes some sense that way, doesn’t it?

It’s amazing how we develop whole social systems and how much people suffer because of wrong views and wrong philosophies, isn’t it? You see, it’s all just dependent on the mind—how people think. And even today, the caste system, as much as Mahatma Gandhi did to try to overcome it, is still alive and well and disastrous for people. So, the third misconception was that the aggregates are empty because they’re not a permanent, unitary, and independent self.

The fourth is that the aggregates are selfless because they are not a self-sufficient, substantially-existent self. A self-sufficient, substantially-existence self is the idea of a self being a controller, in control of the body and mind. This explanation of the third one, empty, and the fourth one, selfless—the third one being the lack of permanent, unitary, independent self, the fourth one being the lack of a self-sufficient, substantially-existent self—is according to the general Buddhist explanation that is acceptable to almost all of the Buddhist schools.

According to the Prasangika, the third and the fourth attributes, empty and selfless, actually have the same meaning. Not only is the self not permanent, unitary, and independent, and also not self-sufficient or substantially existent, but that self—and all other phenomena—including our body and mind, lack inherent existence. So, for the Prasangika, what they’re negating in the third and fourth attributes of true suffering is much, much deeper than the general idea that the other schools are negating: the commonly held view. Because it’s one thing to negate a permanent self because that idea of a permanent self is really gross in the sense of coarse.

Seeing this image of an atman the way it’s described is actually just an acquired affliction. It’s something that people made up by their own conception. Whereas the misconception of the person and aggregates and everything else being inherently existent is an innate affliction. That is inborn. That is the fundamental ignorance. So, what’s in common with all the schools is a much grosser level. It’s good to start out negating that and then progress to the deeper levels, but it’s also important to be aware that there are deeper objects of negation besides just a soul.

Those are the four attributes of true duhkha. We finished one! [laughter] Let’s run through the others.

True origins

Let’s talk about the four aspects of true origins; the true origins are ignorance, afflictions, and karma. And, like I explained yesterday, we often use craving as the example of true origins because of the function that craving plays during our life—and also at the time of death—to cause rebirth again and again and again.

The first aspect of true origins are craving and karma. And here when it says karma, it means polluted karma—karma created under the influence of ignorance. So, craving and karma are causes of duhkha because, due to them, duhkha constantly exists. By contemplating this we develop the deep conviction that all of our duhkha, all of our unsatisfactory conditions, have causes. Craving and karma are these causes, and the result is the duhkha. This refutes any idea that our misery is causeless, that it just happens without any kind of cause. This is helpful to remember because sometimes when we experience suffering, we’re so surprised. We think “How did that happen?” as if it didn’t have a cause and came out of nowhere. We need to realize it did have a cause—craving and karma. And craving and karma can be eliminated.

The second aspect of true origins—craving and karma—are the origins of duhkha because they repeatedly produce all of the diverse forms of suffering, or the diverse forms of duhkha. Afflictions and karma create not just a portion of our duhkha, but all of it, no matter which of the three kinds of duhkha that we’re experiencing. Understanding this dispels the wrong conception that suffering comes from only one cause: the other person, or God, or the devil. “All my suffering is caused by the devil.” Well, actually the devil falls under the next one, the third attribute. But this one is just saying that there is one cause for our suffering when actually it has many many causes.

The third aspect of true origins is that craving and karma are strong producers because they act forcefully to produce strong duhkha. Understanding this dispels the notion that duhkha arises from discordant causes. A discordant cause is something that doesn’t have the ability to produce that particular result. So, here’s where the devil comes in—saying my suffering is due to the devil. Can the devil cause your suffering? No. That’s a discordant cause. Can God’s will cause you’re suffering? No. Can another sentient being really be the source of our misery? No. It all comes back to ignorance, craving, and karma, which can be eliminated.

Then the fourth aspect of true origins is that craving and karma are conditions because they also act as the cooperative conditions that give rise to duhkha. This counteracts the idea that things are fundamentally permanent; instead, they are temporary, fleeting. We’ve talked about this before. If our duhkha was permanent and eternal, it could not be affected by other factors. It could not be counteracted. But craving and karma are not only the main causes of our duhkha; they’re also the cooperative conditions. I’ll tell you the story of my friend Teresa. This is a really good example.

Cooperative conditions

At my first Dharma course in Lake Arrowhead, California, I sat next to a young woman named Teresa. And she had been to Kopan before. She was trying to convince me to go to Kopan Monastery in Nepal for the course there. I thought the Dharma was pretty cool, so I decided to go. She said, “When we get to Kopan, I’ll take you out to Freak Street, and we’ll have some chocolate cake there.” Freak Street was where all the hippies went—all the freaks, all the hippies—and where they made Western food. She said, “I’ll take you out for some chocolate cake when we get to Kopan.”

I get to Kopan, and I’m waiting and waiting because Teresa was supposed to attend the course, and she hasn’t arrived. The first week of the course goes by, then the second week. Teresa hasn’t arrived, and several of us who know her are really worried and concerned about what happened to her. Then we got the news. This was back in the autumn of 1975. At that time there was one French man in Bangkok who was a serial murderer, and Teresa met him at a party. He was very charming. He invited her out to lunch the next day, and then they found Teresa’s body in a Bangkok canal.

This story is a really good story about how the time of death is uncertain. But it’s also a good story about how craving and karma can be the conditions for the ripening of very strong duhkha. Teresa had some strong karma on her mind stream that could ripen in her being murdered, but it could ripen only if the cooperative conditions came together. She went to this party and met this man. What was the mental state of meeting somebody she was attracted to? Attachment and craving. He asked her out for a meal. She accepted. I’m sure he took her out for a very nice meal. Again, there’s more attachment. You can see that set-up the condition for the ripening of that heavy karma.

It’s kind of like driving under the influence or doing anything under the influence. We could have some very heavy karma there. It hasn’t ripened yet because the cooperative conditions aren’t there. When you drink, when you smoke dope, when you misuse prescription drugs, you’re setting up the external situation so that it becomes very easy for some negative karma to ripen.

This doesn’t mean that every time somebody has some heavy, negative karma ripen it’s because they were under the influence of afflictions at that moment. It doesn’t mean that. But it does mean that when we let our mind go under the influence of afflictions, it really helps the negative karma to ripen. You drive under the influence. What are you setting yourself up for? It’s a set-up for suffering.

I’ll tell you another story about that. Many years ago, I was teaching in a different state, and somebody was driving me somewhere. We had a long time to talk in the car. I asked about her family, and I can’t remember how many sons she had but one son had died. She told me the story of how her son died. Her husband liked to drink, and he saved all of his whiskey bottles and wine bottles and everything. You know how some people are proud of drinking and they save all their bottles. He was like that. Around their house he had shelves of samplings of all the different kinds of alcohol bottles representing all the different kinds of alcohol that he had sampled, from a very refined this to whatever. Clearly, the father drank a lot.

The son followed in the father’s footsteps and started drinking. So one day when he was in his early twenties, the son caused an accident because he was under the influence. I think there were three or four people in the other vehicle who died because of the accident. And the son was very severely injured, and they had to put him on life support. After the accident, after a while of him being on life support and not coming out of the coma, the parents were faced with the decision of what to do. Do they pull the plug or keep this person alive?

Can you imagine being a parent forced to make that decision? It’s horrendous for the parents. And they decided to pull the plug and their son died. And the father went home and looked at all of his alcohol bottles and just broke them all. He realized that somehow his behavior had an influence in this whole thing.

Craving and karma are also conditions for very strong duhkha. This is the value of the five precepts and why the precepts are such a protection. Because when you refrain from killing and stealing, from unwise and unkind sexual behavior, and from lying and from taking intoxicants, you are protecting yourself so much in many ways. Because you are protecting yourself from doing the actions that could act as conditions for the ripening of negative karma. You’re also protecting yourself from doing the actions that create the negative karma that can ripen in different situations in your life or what you’re reborn as. So, precepts become incredible protection.

Okay, I got sidetracked a little bit. We still have ten more minutes. [laughter] But, I’m hoping that, you know, something strong is going in there.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Right. Well, it’s the same thing, the same thing. As much as we disengage from the ten non-virtues, we protect ourselves from the ripening of other karma and from creating the karma that creates direct misery.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Definitely. You stop serving alcohol, so you’re not going to be the condition for somebody else getting drunk. And I think as parents, the example that you set for a child is incredibly important. Because children watch what you do, not what you say. My mother used to say, “Do what I say, not what I do.” No, sorry mom. That wasn’t correct.

True cessations

The example given for true cessations, like I explained yesterday, are the different levels of the ceasing of afflictions and, therefore, of the duhkha that they create. Here, we’re saying,

The first aspect of true cessation is the cessation of duhkha because, by being a state in which the origins of duhkha have been abandoned, it ensures that suffering or duhkha will no longer be produced.

Understanding that attaining true cessation is possible by eliminating the continuity of afflictions and karma dispels the misconception that liberation does not exist. That’s very important because if we think liberation doesn’t exist then we won’t try and attain it.

The second aspect of true cessations:

True cessation is peace because it is a separation in which afflictions have been eliminated.

Some people, instead of seeing the qualities of actual liberation, mistake other afflicted states as liberation. For example, some people attain the meditative absorptions in the form realm or the formless realm. These are very high states of meditative absorption. And because the mind is so peaceful in those states, they mistake them for liberation. In fact, the person hasn’t eliminated ignorance. They haven’t realized emptiness. So, this is a really big boo-boo, to think that you’ve attained liberation when you haven’t, because then, when that karma for that rebirth ends, plunk, they go down into more unfortunate realms.

Then third is aspect of true cessations:

True cessations are magnificent because they are the superior source of health and happiness.

Because true cessations are completely non-deceptive—and no other state of liberation supersedes it or is better than it—true cessations are magnificent. It’s their total freedom from the three kinds of duhkha that we were talking about earlier. Again, this prevents mistaking certain states of partial or temporary cessation as final nirvana.

A person might think, “Okay, I’ve subdued my anger. That’s liberation.” Well, no, you still have ignorance. And the anger hasn’t been completely eradicated. It keeps us on our toes so that we can really identify correctly what the source or origin of our duhkha is, and that we make sure we really practice the path entirely so we can attain actual true cessations instead of some inferior kind of state that seems better than where we were before.

And then fourth aspect of true cessations:

True cessations are definite emergence because they are total irreversible release from samsara.

Liberation, true cessation, is definite abandonment because it’s irreversible. In other words, once you have attained actual true cessations it’s impossible to lose them. You never fall down again. So, if we’re people who are looking for security, true cessations are the ultimate security because they are states in which the causes of duhkha and the corresponding levels of duhkha have been eliminated; they can never appear again ever. That’s real security. Financial security—forget it. You never attain financial security no matter how much money you have. Do you? No matter what situation you’re in, there is never any lasting security except for true cessations.

Okay then, those are the four aspects of the path. In the Theravada tradition, the Pali tradition, they talk about “the here” as the example. From the Prasangika Madhyamaka system, we talked about it being the wisdom that realizes the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths, and especially nirvana. Actually, that wisdom realizing the sixteen aspects—and especially nirvana—is common to all of the Buddhist schools. But especially from the Prasangika Madhyamaka view, it’s the wisdom realizing the emptiness of inherent existence of both persons and phenomena.

True paths

This wisdom that realizes the four noble truths, especially realizing nirvana, especially realizing emptiness, this is the wisdom in the continuum of an arya because an arya has realized the ultimate nature directly.

The first aspect [of true paths]is the wisdom directly realizing selflessness.

Here “selflessness” means emptiness, from the Prasangika view.

The wisdom directly realizing selflessness is the path because it is the unmistaken path to liberation.

Knowing this counters the misconception that there is no path to liberation. So, again, that’s an important misconception to counter, because if we think there is no path, or if we think there is no liberation, then we don’t even set out on the path and start practicing. This wisdom leads us to the destination of liberation, or nirvana, or true cessations.

The second aspect of true paths:

The wisdom directly realizing selflessness is awareness because it acts as the direct counterforce to the afflictions.

The wisdom realizing selflessness is a viable path because it’s a powerful antidote that directly counteracts the self-grasping ignorance—the ignorance that grasps at true existence—and by eliminating that ignorance directly, then eliminates duhkha. Understanding this eliminates the misconception that the wisdom realizing selflessness is not a path to liberation. It confirms for us it is a path. It is a reliable path. There is a path.

The third aspect of true paths:

The wisdom directly realizing selflessness is accomplishment because it unmistakably realizes the nature of the mind.

Unlike worldly paths—like states of deep meditative absorption, because these worldly paths cannot accomplish our ultimate goal—the wisdom directly realizing emptiness leads us to unmistaken spiritual attainments. So, this wisdom is accomplishment because it accomplishes those attainments. It accomplishes the true cessations that we seek. It’s an unmistaken path.

This counteracts the misconception that worldly paths eliminate duhkha. In other words, the misconception that any of the things that so many other people teach—that deep samadhi eliminates duhkha or that propitiating a certain deity eliminates duhkha—this third aspect eliminates those kinds of wrong conceptions.

And the fourth aspect of true paths:

The wisdom directly realizing selflessness is deliverance because it brings irreversible liberation.

When we have this wisdom realizing selflessness, and it eliminates the different layers of afflictions and different layers of duhkha, we attain those true cessations that themselves are irreversible. This path is really deliverance because it leads to those irreversible states. It leads to irreversible liberation.

So, once you’ve attained liberation, you can’t lose it. Once you’ve eliminated ignorance from the root, there is nothing that can cause the ignorance to come back in the mind. Until we’ve eliminated ignorance from the root, the ignorance can come again. But once we’ve eliminated it through this wisdom—because the wisdom realizes the opposite of what ignorance holds—it directly counteracts ignorance. Because of this, then, the afflictions can be eradicated forever and true liberation attained. And we never fall from that. So, that eliminates the misconception that the path is mistaken or that the path leads to a state of liberation that’s only temporary.

We did all 16 aspects. [laughter] Yes?

Questions & Answers

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Here, if you describe it according to the Prasangika view, yes. Selflessness and emptiness have the same meaning.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: There are two different aspects. One is cause; one is origin. The thing is, with these different aspects, they’re pointing out that that’s what they are: they’re aspects. They’re showing us different ways to regard that particular truth, different aspects of that truth.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Craving and karma are the examples that are used. All these 16 aspects are syllogisms; if you study reasoning, they’re all syllogisms. Craving and karma are the causes of duhkha because, due to them, duhkha constantly occurs. Craving and karma are the examples of duhkha. They’re the subject of the syllogism. And they are causes of the duhkha. That is the thesis—what you’re trying to prove. Why are those the causes of duhkha? Because due to craving and karma, duhkha constantly exists. That’s the reason.

Audience: Can you go through the fourth one—true origins?

VTC: True origins? Yeah, okay:

Craving and karma are conditions because they act as the cooperative conditions that give rise to suffering.

Audience: And the thing that it counteracts?

VTC: Oh, what it counteracts? It counteracts the idea that duhkha is fundamentally permanent but temporarily fleeting. Because if suffering were permanent and eternal, it couldn’t be affected by other factors, and, thus, it could not be counteracted. So understanding that duhkha depends on causes and conditions and that those causes and conditions can be eliminated shows us that duhkha can be ceased.

Audience: Are you saying the wisdom directly realizing emptiness counters the idea that there is no path to liberation. So, until we have that direct realization, we can always be plagued by doubt?

VTC: Well, they say that it’s only when you realize emptiness directly that your doubt is cut-off from the root. However, there are many levels and types of doubt. As we practice, and especially as we learn about emptiness, and as we gain a first correct assumption about emptiness, then later an inference about emptiness, those are very strong things that oppose the doubt. It isn’t that you have doubt or wrong views up until one second before you realize emptiness directly. You go from wrong views to doubt, from doubt to correct assumption, from correct assumption to inference, from inference to direct perception.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: You can see it this way: true cessations are the destination where you’re going. And the wisdom realizing emptiness is the path that’s going to take you there.

Audience: Where do we find that? Is there a “Step 1?” [laughter]

VTC: Step 1: follow the lamrim. The lamrim is called “Stages of the Path.” You start at the beginning and go through. [laughter] Sometimes we need some introduction to the lamrim. We Westerners don’t always have the world view associated with the lamrim. So often, we need some introductory steps before we get it. But if we really start practicing that way, then we’ll get there.

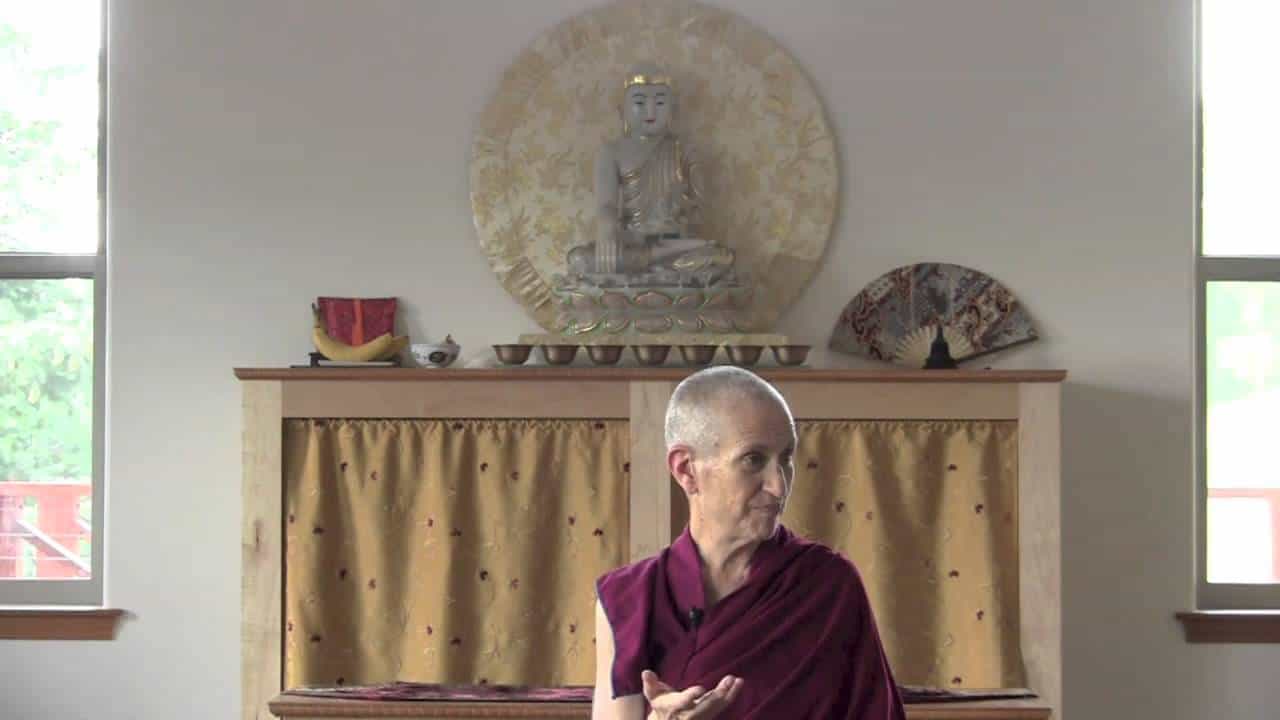

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.