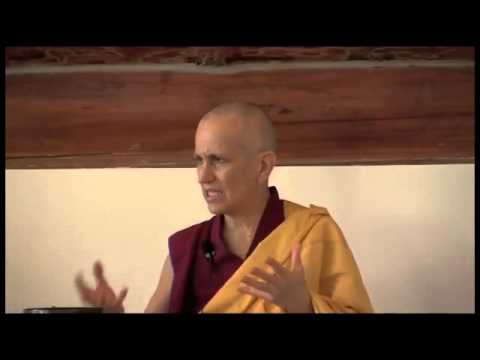

Bodhisattva ethical restraints: The five hindrances

Part of a series of talks on the bodhisattva ethical restraints. The talks from March 7-10, 2012, are concurrent with the teachings on Nagarjuna given by Guy Newland, which are often referred to in the teachings.

- Auxiliary vows 24-26 are to eliminate obstacles to the far-reaching practice of meditative stabilization. Abandon:

Let’s bring ourselves back to a bodhicitta motivation. Let’s remember our long-term goal, our long-term objective, and bring into the forefront of our mind the meaning of our life, the purpose of our life, and a strong determination to live according to that meaning, that purpose of progressing on the path, so that we can become ever more capable and wise in benefiting others and ourselves. Then let’s continue talking about the bodhisattva precepts.

Clarifying an earlier teaching

There were a couple of things I thought to comment on very briefly from Guy’s teaching this morning— what he went through first in the class, the rest of chapter twenty-four; he went through it very quickly. For me, that’s one of the juicy parts in the Kārikās, the whole section that proves the existence of the Triple Gem, because by using reasoning to prove that all phenomena are empty of true existence, you can prove that it’s possible to eliminate the ignorance and the afflictions. If it’s possible to do that, then you have the true path and the true cessation, you have the Sangha, and you have the Buddha. So, it’s a brilliant argument on Nagarjuna’s part to really prove to us the existence of the Three Jewels. At the beginning of the practice I used to think, “How do I know Buddha even exists? It sounds good, but how do we know Buddha exists?” So, this is an incredible way to prove it to ourselves. Of course, you must have some feeling for the reasoning about emptiness to get it. You must understand a lot of different things about the path, but it’s a way to do it. That’s one thing I wanted to comment on.

And there’s another thing I thought to comment on. I didn’t look at the book again, but I remember there being something about not just giving girls to whomever wants them, but when you’re entertaining the ministers and other important people, as a courteous host you give them women to sleep with. I’ve always wondered about this. How can people realize the nature of reality and yet what seem to us very coarse conventional beliefs don’t get questioned? I’ve always wondered about that. I wonder if they just didn’t question them, or if Nagarjuna felt like there were all these important things he had to get across to the king, and if he were to challenge him about this cultural convention, the king would totally freak out and not believe anything else. Because it was such a part of the culture, Nagarjuna just went along with the culture. But it’s always puzzled me. If you want to benefit all sentient beings, why don’t you want to liberate them from being sex objects in somebody else’s mind? What a horrible trap—you’re trapped in that role of being a sex object, which is yuck. It’s just always surprising to me. Anyway, that I guess, is our koan. [laughter]

Audience: [Inaudible]

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Right, that’s what I mean. Maybe he saw that challenging it would cause problems. Because he was just working on the king. So, maybe it was just saying something like, “Let’s see the filth of the body,” which is completely okay with me, because all our bodies are filthy—just work on that, but don’t question the social structure. Maybe he was focusing on that, and it was one thing at a time with the king.

Audience: I was thinking maybe he hoped the king would see the contradiction and have a realization.

VTC: Yes. Wouldn’t that be nice? The king realizes, “Oh, they’re human beings!”

Audience: Could you say again the reasoning that proves the Buddha?

VTC: The reasoning that proves the Buddha: If the source of our suffering, our karma, which comes from affliction, which is rooted in ignorance, and ignorance grasps at inherent existence, and yet things exist in the exact opposite way from the way ignorance holds them, then ignorance can be eliminated. If ignorance can be eliminated by generating wisdom, that’s the true path. That wisdom is the true path. It brings about the elimination of degrees of ignorance; that’s the true cessation.

The true path and the true cessation are the last two of the noble truths, and they’re also the Dharma jewel. So, you have the four noble truths in there, but you have the Dharma jewel. If you have the Dharma jewel, there’s got to be people who have realized it. That’s the Sangha jewel. If you have the Sangha jewel, then through people practicing the Dharma jewel more and more and purifying their minds, the Sangha can become Buddha, and you have the Buddha jewel.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: The way His Holiness the Dalai Lama explains the whole thing about omniscience is to say that the nature of the mind is clarity and cognizance. The very nature of the mind is to cognize things. So, if it’s not cognizing something, that means that there’s some obstruction. Some of the obstructions can be physical, like, “I can’t see on the other side of the wall.” Some of them could be a defect in our sensory organs so that they don’t connect with the data. But then there’s another kind of obscuration, which is the karmic obscuration and the afflictive afflictions and the cognitive obscurations. If you can eliminate all those obscurations that obscure the mind’s very nature, which is to be cognizant and perceive things, if you clear away all those hindrances, then by its nature the mind is going to perceive everything.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: That is interesting, isn’t it? Very compassionate towards prisoners, but toward women, it’s another story.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Right, stop hunting with a gun, but hunt with your lust. It’s quite interesting, isn’t it?

Audience: Along the lines of omniscience, this is going to be a dumb question. Nagarjuna’s saying nothing is self-causing and that everything arises contingently. But on the other hand we have conventional truth of free-will—that we can choose to follow the path of the bodhisattva or not. But we know that we have a certain set of causes and conditions—coffee seed, coffee plant—how are those reconciled? Free will versus dependent origination.

VTC: Yes, it is quite interesting that the subject of free-will and predetermination never came up for the great Indian philosophers. This thing that has been so much at the root of theistic religion never came up for them. Probably because they think of things in terms of dependent arising. Whereas if you posit a creator and a manager of the universe, then free will is really a big deal. But it depends how you define free will; if it means I can do anything I want independent of causes, clearly that is impossible because there must be causes for things. Within there being causes, we can choose this way or that. But I cannot choose in the very next moment to speak Chinese because I have not created the causes to do it. So, we should not think of free will as you can do anything independent of causes and conditions, because that kind of situation doesn’t exist at all. That is totally opposite to dependent arising.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Oh, that’s just the definition of the mind—clarity and cognizance. There is not a logical argument to prove it. It’s just the characteristic of the mind.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, but you look in your own experience and ask, “Is the mind formless? Does it know things? Yes.” It’s like, “What’s the nature of fire? Hot and burning.” You don’t need a logical argument; that’s just what fire is. So, what is the mind? It is clarity and cognizance. With fire, you test that out—“Is the nature of fire hot and burning?” You put your hand in it, and yes, that’s true, fire is hot and burning. “Is the nature of mind clarity and cognizance?” Clarity, yes; formless, yes; cognizant, yes; the mind knows objects.

Audience: How do you define clarity?

VTC: There are different ways to define clarity, but one of the ways means that the mind is formless; it lacks material substance. Another way is it has the ability to reflect objects.

Audience: Does the Buddha cognize objects non-dualistically? Or does he cognize the minds of the beholder of the objects?

VTC: The Buddha cognizes everything non-dualistically. Any of the meanings of dualism include some kind of obscuration or pollution on the mind, and the Buddha does not have any of that. Truly existent things appear to the Buddha’s mind but not through the Buddha having obscurations, but simply because the Buddha knows what appears to sentient beings’ minds. The appearances of true existence appear to sentient beings’ minds, so the Buddha knows that. It’s like, there’s a disease where the eyes see falling hair, and if you were clairvoyant, your eyes wouldn’t see falling hair because your eyes are in good shape; but if you’re clairvoyant and your friend standing next to you is seeing falling hair, you would know that. But that doesn’t mean that you’re seeing it from your side; you’re just seeing it because you know they see it. Like that.

Okay, let’s talk about bodhisattva vows.

The obscuration of ill-will or malice

We were in the middle of talking about the five obscurations, and we were getting to the third one, which is ill-will or malice. He says this one:

—is the desire to cause harm to another being. It is brought on by incorrectly paying attention to an object that we consider objectionable or repulsive or by brooding over the harm that others may have inflicted upon us.

So, it’s incorrectly paying attention. There is one mental factor called inappropriate attention. There are many kinds of inappropriate attention. One of them is considering impermanent things to be permanent, things that are dukkha by nature to be blissful, things that are impure by nature to be pure, and things that don’t have a self to have a self. Other kinds of inappropriate attention exaggerate the beauty or exaggerate the harm of other objects.

In the case of malice there is an object that we consider objectionable or repulsive, and the inappropriate attention has really magnified that, so we have animosity and the wish to strike back and harm. Then, we not only have that, but sometimes we really get into it—we sit and brood about it—“Oh, this person said this to me. Fifteen years ago they did this, and then fourteen years ago they did that, and thirteen years ago they did the same thing, and twelve years ago…”

We sit with our whole counter of all the things we consider wrong that this other person did, we never miss any of them. And then we make a whole court case in our mind. There is the prosecutor, the judge, and the jury, and we convict the person for doing horrible, disturbing, unforgivable actions and conclude that they deserve to be flogged. We then meditate on how to flog them—whether to say something nasty to their face or behind their back, or punch them in the nose, or tell their mother, etc. That’s this precept. It is a hindrance to developing concentration. But what is interesting is we can get into a whole meditation completely focused single-pointedly on the harm somebody gave us, how much they deserve to suffer as a result, and plan step by step exactly what we’re going to do to get even. We can spend quite a long time without any distraction. Isn’t that amazing?

So, what is the antidote to this one?

Audience: Love.

VTC: Yes, cultivating love. Of course, that is the exact opposite of what you want to do, which is why that’s the antidote.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, any of the bodhicitta meditations. Practicing patience, learning to look at the situation differently. Why am I feeling misery right now? Because of my own actions done in the past, under the influence of my own self-centeredness. If I hadn’t done nonvirtue in the past, I wouldn’t be receiving this harm.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Exactly. I’ve dished it out. Whatever this person is doing to me, I’ve done it to other people many times. So why am I complaining when it comes back to me?

So, you can use any of these methods for practicing fortitude and patience or the methods for generating love. You also can think of the disadvantages of it. Because if you really want to develop concentration, then sitting and mulling over all the harm people have done and how they have been so mean to you is not going to help you develop samadhi. It is also going to make you quite miserable in the process.

The fourth obstacle is attraction to desire-realm objects. In other words, the five objects of the senses—sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and touches. It arises when we find an object, such as sound, extremely attractive and we either attribute qualities to it that it lacks entirely or exaggerate the qualities that it has. In other words, it is based on an inaccurate apprehension of the object’s real nature.

Here, we are not only not understanding the object’s ultimate nature, but we are also not even understanding its conventional nature correctly. Again, this is inappropriate attention—we are exaggerating the good qualities or projecting good qualities that are not there.

If we look at our lives, we see that we are so under the domination of our senses. Just look: all day long we are so reactive to what appears to our senses. There is something beautiful, there is a beautiful sound or a smell or a taste or a touch, and we are so reactive to whatever sensory information we get. And not just reactive, but immediately like, “Oh, this is too cold,” or “Oh, that feels good.” Then, we start thinking about those sensory objects with our mental consciousness, and we build all sorts of stories about them—“Oh, this object is so beautiful because I must be this fantastic, wonderful person, and that’s why I’m coming in contact with it; but no, I don’t really deserve it, so I should give it away.” Or “I’m worried and anxious because somebody else is going to take it or it’s going to get destroyed.” We started out just based on some sensory perception, and then we make this whole drama around it.

That is the mental consciousness. The immediate reaction to the sensory perception also has to do with the mental consciousness; and it dominates our life. We are getting along completely fine, then we hear even a few words, and we make up a story. Then we are furious, and that takes over the entire day. Or we are feeling down, then there is some small, beautiful thing we see, and all of a sudden the mind gets so excited, it fantasizes this big something, and everything is wonderful. We are so unstable, aren’t we? We are completely unstable, and that is considered “normal” in this world. You are supposed to go up and get excited about beautiful things, and you are supposed to go down when there’s unpleasant things. That is what being normal means, all day long.

Audience: No wonder we are tired.

VTC: Exactly! No wonder we need to go to sleep at night. It is exhausting being so reactive, so reactive.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: In one way, you can look at it and say we have more things coming at us than people in a very simple society had. The other way of looking at it, as His Holiness always stresses, is that we sentient beings all have the same mind; it doesn’t matter the historical period. You can be sitting in the countryside where there is nothing going on and start making up stories about the trees. We do that. You can sit out here, so peaceful, and “Oh, that tree doesn’t look right; we should move this tree here and that one there, trim this tree, and why is the branch growing this way?” So, in one way you can say we have more coming at us, but in another way that is also a function of our own mind, a mind so completely enamored by external objects.

Audience: In the degenerated ages, normally is it true that we do not have so much connection to the Buddhadharma?

VTC: Well, degenerated could mean in the sense that the environment comes more at us, but it also could be that our afflictions are extraordinarily strong.

Audience: Stronger than before?

VTC: Sometimes when they talk about thought training being good for a degenerate age, when they talk about a degenerate age, one of the qualities is sentient beings have extraordinarily strong afflictions.

Audience: Why then? Why do we have more now than before?

VTC: Because the book said so. [laughter]

Audience: That is why I don’t like to study.

VTC: But you see, this is the thing. We can see that on one hand, society has changed, and there is more stuff coming at us. In another way, we have the same human mind. In another way, you look and see that yes, maybe the afflictions are a little bit more active than in past centuries. But on the other hand, they are the same afflictions. We have Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin in the modern age, but who did we have in the past? We had Peter the Great, Caesar, and all those people in the past, too.

Audience: They did not kill as many people.

VTC: But they had the same mental state. If they had had the technology, they would have killed millions of people. It’s just that they didn’t have the technology to do it.

Audience: It’s absolutely false to believe that this age is more violent than in the past. And the likelihood of being killed, even with Hitler and Mussolini and all those guys, is a lot lower than it was in the past.

VTC: We’re getting off the topic.

Audience: When they say the “degenerate age,” they were talking about the degenerate age back 2,000 years ago.

VTC: Yes, they have always been talking about it.

Audience: So, they weren’t talking about now, they were talking about their present.

VTC: Well, everybody always sees themselves as living in the degenerate age, don’t we? But also, we are at the age when there is more hope, and more people are tuning in. So, all that kind of talk about a degenerate age, I don’t pay much attention to it, because I think the real thing is what is my experience and what do I need to do to improve it, rather than building a case of, “Oh, it’s harder now” or “It’s easier now.” What difference does it make if it is harder or easier now? It is what it is.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Right, yes. Right, we are still here.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, we created the cause to be born in the situation we are born in.

Okay, so what is the antidote to that? Besides getting all distracted, debating whether it’s worse now or better now.

Audience: Meditating on the shortness of life.

VTC: Yes, meditation on impermanence and death. Meditating on impermanence and death assumes that beforehand you have meditated on the precious human life—its rarity and its purpose. You must do that meditation on the precious human life beforehand. Otherwise, if you only meditate on impermanence and death, you come out with the wrong conclusion. You must see your life as something valuable and precious, and then see, “Oh, it’s hard to get, it has great meaning, but the time is clicking away. So given that the time is clicking away, am I going to let my mind get distracted and so reactive to every small thing somebody else does?” Because that’s the way our mind is—every small thing is all related to “me.” It means they like me, it means they don’t like me, it means I’m worthwhile, it means I’m not worthwhile, it means the world is ending, it means the world is not ending. The mind is so reactive to external things.

Considering that we are able to practice the Dharma and the time we have to practice is getting shorter moment by moment, do we have the time to waste getting distracted by all the stupidagios? We don’t. We don’t have that time. We have this pattern of stupidagios—they come in the mind, and then we say, “I just don’t have time for this, goodbye.” That’s the time when we should be saying, “Oh, I don’t have time.” Usually we say “sorry, I don’t have time” when it’s time to study the Dharma texts. Or it’s time to go to retreat—“I don’t have time.” It should be, “Oh, this person looked at me cross-eyed, and it means that I’m totally a horrible person, and they’re rejecting me forever, and my life is meaningless,” and that’s the time when we need to say, “I don’t have time. I don’t have time for those stupidagios in my mind.” Because they take up so much time, don’t they?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, your whole life. Your whole life. Remember earlier in the book he was talking about spending a lot of time talking about our childhood. We could spend our whole time talking about our childhood—”This happened and that happened, and this happened and that happened”—and it’s all external objects. Okay, there was conditioning there, but it’s not happening now, and all that conditioning was just our deluded interaction with external objects. It wasn’t anything real and solid, and it’s not happening now, so who has the time to live in the past when you have a precious human life and it’s getting shorter moment by moment?

Remembering this gives us some energy. It is time to cut this junk instead of holding it so dear. You know how it is—“my inner child, my trauma.” I am not trying to put down traumas. People get traumatized, but it is not happening now, it is over and done with. And it’s simply our reaction to external things that are like illusions that we’re perceiving inaccurately to start with. So, let’s use our beautiful potential and do something meaningful. I’m not saying to repress stuff, I’m not talking about repressing it. I’m saying just look at it for what it is. Where is it? Where is it? Goodbye! I’ll hug my traumas one more time and then let them go home, let them dissolve back into emptiness, I don’t need to make them my identity.

The fifth obstruction is doubt—

I don’t know if I can actually teach about this one properly. [laughter]

—Which is defined as being of two minds regarding the truth. It is therefore a form of indecision or hesitation regarding important matters.

These are key words: “important matters.”

We may be indecisive about whether or not we have had past lives and whether we will have future ones and whether or not there are such things as the Three Jewels, the four noble truths and the law of karma and its effects. This kind of hesitation is brought on by incorrect attention, or “inappropriate attention,” and naturally interferes with our concentration.

This is doubt about important things. It is not doubt like, “Oh, did I turn the washing machine on to full-cycle or half-cycle?” Or “Did this person give me a dirty look once or twice?” It is not that kind of doubt. This is doubt over important things. It is important whether there’s past and future lives; that’s important because that’s definitely going to influence the choices we make in our life. It is important whether the Three Jewels exist and whether or not it’s possible to attain enlightenment; that’s important because that’s going to influence what we do with our life. Whether our actions have an ethical dimension is important; that will influence what we choose to do and what we choose not to do.

Those kinds of things, when we have doubt about them, what’s the antidote?

Audience: Investigate.

VTC: Yes. Study, investigate, think about things, ask questions, discuss with your friends.

There is one kind of doubt that is this little spinning doubt, like, “Ahhh! I don’t know. Make me believe. I don’t believe in past lives, make me believe. It’s your responsibility to make me believe something. It’s not my responsibility. You’ve got to make me believe.” Where’s that coming from? This kind of doubt is useless skepticism. So, put that with your inner child that went to daycare, okay?

Audience: Inappropriate attention—how does that figure into the doubt?

VTC: Into the doubt? Because inappropriate attention will go, “Well, I don’t know… I did this action, but is it virtue, is it non-virtue? I gave this person some poison, but I had a good motivation of compassion because they’re going to use it to kill their enemy. Is that really going to have a harmful effect?” Inappropriate attention does not know how to understand things properly. Or the thing of whether the body is pure or foul—“Well, I think it’s kind of nice, it’s clean. Nagarjuna didn’t know what he was talking about, and neither did Shantideva. The body’s perfectly clean, I took a shower today.” That’s inappropriate attention.

Audience: Is this the mind that likes to twist itself around and around and around?

VTC: It’s the mind that doesn’t see things clearly, exaggerates different things, and makes up stories. The inappropriate attention is part of the creative writing department.

Audience: Would it be something like, “I don’t know why this person is hurting me, I’ve never hurt someone before.” It’s lack of attention to my past deeds in relationship, with inappropriate attention for some of the karma, thinking I’ve never done this before.

VTC: Right. If you start doubting karma in that way, saying, “I never did anything to anybody, so why are they doing this to me? Karma doesn’t exist.” Yes, that would be a good example.

Audience: In Precious Garland, Nagarjuna did distinguish between wisdom and faith, though with faith, karma, and rebirth my understanding is that there are things that just require faith. As Guy said, faith is the prerequisite to that reasoning and wisdom . . .

VTC: With karma and its effects, they say that only the Buddha fully understands that. But there is much debate about what that means. Does that mean just the general principles of karma, only the Buddha really understands it? Or does it mean the details like you are sitting in this room because fifty-million and two lifetimes ago you did this action that took 5.5 minutes? Is it that kind of detail? Everybody agrees that only the Buddha has that kind of understanding.

But the general principles? I think it is possible for you to get a feeling for the general principles. You can sense that having a generous open heart creates some kind of energy. It makes sense that generosity is the cause of wealth, doesn’t it? It makes more sense than stinginess being the cause of wealth, which is the normal way people think—“If I’m stingy, I’ll be wealthier.” But if you really think about it, is stinginess the cause of wealth? Or does it make more sense that generosity is the cause of wealth?

And how about when they say that practicing patience makes you more physically attractive? Well, even in this life, it is true, isn’t it? People’s faces are so ugly when they are angry. So, it makes sense that if you practice patience, in a future life you will look more attractive. I think we can get some idea about these kinds of things.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Dana usually means generosity.

Coming back to your thing about faith. I think there are some things that you can get some kind of idea about just by thinking of them in a spacious way. You may not have the clairvoyance that can see, “Oh, why did I have lunch today? Well, it’s because in a previous live, I gave so-and-so some food.” You may not have that detail, but you can get some kind of feeling about it.

What I thought was so interesting about faith and wisdom when we talk about the Eightfold Noble Path is that the first one is Right View. When you first start practicing, Right View is the first thing you develop. Right View refers to having some kind of conviction in karma and its effects, because that is what you need at the beginning of the practice in order to begin practicing. If we do not start choosing ethical actions, the rest of the practice is going to be difficult.

They explain the Eightfold Noble Path starting with Right View and Right Intention. When you get to Mindfulness and Concentration, you come back to Right View again. But this time it is Right View that understands the ultimate, that understands nirvana, that understands emptiness. So, you start out with some kind of Right View about karma and its effects, which is the faith thing, and then after practicing all the other seven factors, you come around to Right View again. But this time it’s a deeper level of Right View, which is the wisdom.

Audience: I think one important thing about doubt is to remember that you have an obscured idea about what you are doubting. In other words, this is how I view it: I doubt how I hold the concept and tell myself I do not really know the true meaning of what I have doubts about. If I have a reified view of things, thinking that things are real, and I say, “Well, I doubt that there’s a buddha,” it is because the picture in my mind is of a solid, self-existent buddha. That’s what I’m doubting. I don’t have a good concept that I’m thinking about, and that’s where my doubts are coming in. I’m thinking about things the way I always thought about them, and I haven’t developed the wisdom to see things in a more spacious way.

VTC: When our mind is afflicted by doubts, a way to practice is to remember that we do not perceive everything accurately, so of course there is going to be doubt, misconception, and confusion in the mind. This stops us from getting so reactive to the doubt, like thinking, “Oh, my doubt is bad and I’m bad,” and all of that kind of stuff. Instead, we can think, “Of course I don’t perceive the nature of reality, so let’s get to work here.”

In general, there are a number of factors contributing to the appearance of afflictions, like attachment in our mind. The lamrim gives six causes that can be condensed into three. The first general condition is the presence in our mindstream of the seed of an affliction that we have yet to eradicate.

We will come back to this because I’d actually like to spend some time talking about these six factors that make the afflictions arise.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.