Mindfulness, contentment, and ABBA

By J. S. B.

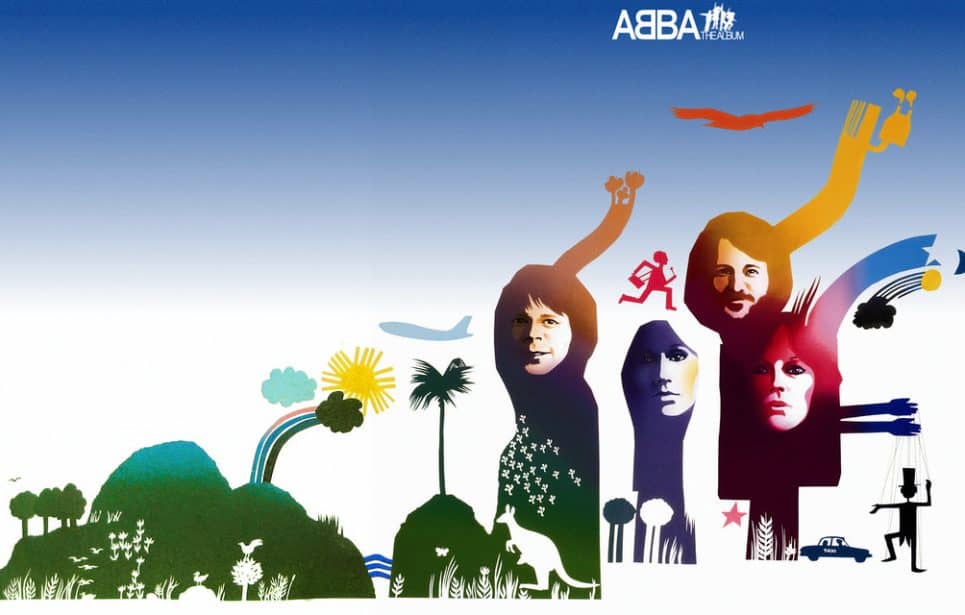

“ABBA, Jeffrey?”

“What?” I stopped writing in my journal and looked at my cellie whose name is also Jeff. Around here, we’re known simply as “Jeff Squared.”

“You were singing an ABBA song, Waterloo.” He shot me a look of concern which quickly dissolved into disgust.

“I was? Geez, sorry.” What was happening? The day before I had caught myself singing a Bee Gees’ song, How Deep Is Your Love. Singing ABBA and Bee Gees songs in prison isn’t a good thing, it is much better to sing a rap ditty by Eminem or 50 Cent. Back in the 70s, I despised ABBA and the Bee Gees, and now, years later, here I was spouting lyrics of songs I didn’t even know I knew. I had a theory. This sudden 70s pop music revival was a result of my meditation practice. I was sure of it.

I was introduced to Buddhism by one of my first cellies. I’d struggled with spirituality all of my life. In my 20s, I was born again—it seemed the appropriate thing to do at the time, after all, our president was. In my 30s, I became a Catholic, but as much as I loved the Church, I was still lost and confused. My 40s saw me battle depression and anxiety; I had a nervous breakdown, spent some time in a mental hospital, then ended up in prison.

When I first read the four noble truths, it was as if someone had hit me square in the forehead with a board. Whack! These simple principles said it all. Within the first two truths was the stark reality of my life. I could be the poster boy for the second truth. And there was so much hope in the last two. I—yes I, Jeff—could cease my suffering by following the Buddha’s way. I eagerly began my journey down the path.

I read and practiced the Dharma, and began meditating daily. The concept of mindfulness, being here in the moment, totally aware, appealed to me. I’ve spent most of my life anxiety ridden about the future or full of guilt about past mistakes. I had an attention span of three seconds.

For months I practiced mindfulness meditation, diligently counting my breaths, barely able to count beyond three or four before my mind would tromp off to who knows where. What’s for dinner tonight? I feel fatter today, I know I’m gaining weight! My nose itches. I stuck with it, determined to develop this thing called mindfulness.

Then, people from my past started popping into my head during meditation. Suddenly, I remembered Sue Baily, a girl I sat beside in Theater 101 at Ohio State. Sue was a veterinary science major from Lima, Ohio. She took great notes that she’d graciously share with me whenever I skipped class, which was often since it was an eight A.M. class.

I remembered Chester Ison from fifth grade. Chester had a glass eye. At Halloween, instead of wearing a costume, he’d just take his eye out, hold it in his hand, ring the door bell and yell “trick or treat.” Once, in the boys’ restroom, he took his eye out and let me peer into his head. Why, after all of these years, were these people wandering around in my head?

Next came the music. Songs I once hated, I was suddenly singing ABBA, the Bee Gees, Barry Manilow, K.C. and the Sunshine Band. I sounded like a 70s compilation album by K-tel.

Why was this happening? My theory was simple. I had, through my meditation practice, and with impressive speed, stripped away all of the gross levels of consciousness and tapped into my subtle mind. I’d read about this in one of the Dalai Lama’s books. The problem was my subtle mind appeared to be full of people I’d forgotten about and lyrics of dreadful pop songs. It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Undaunted, I practiced more, meditated longer. Then something happened.

We were all in the chow hall eating lunch, me and my Buddhist friends. As I was about to open my pudding cup, Brad said, “Wait, save it. Smuggle it out and we’ll have a special Buddhist ritual tonight.”

“Really? Cool,” I said as we all pocketed our vanilla pudding cups. We then successfully eluded the officers searching exiting people.

That night, out on the cold, windy, deserted rec yard, the four of us, bundled up in our matching khaki coats and bright orange stocking caps, sat around a blue, steel-mesh table.

“This secret Buddhist ceremony is called the Decadent Dessert Rite,” Brad said. “The monks in Tibet, normally sustained by a diet of rice and broth, would occasionally sneak out at night and feast on fine cakes and sweet breads.”

“You’re making this up, aren’t you?” I asked.

“Shut up and open your pudding.” We all popped open the lids of our pudding cups. Brad pulled out a box of Raisinettes, dumped some into his pudding and passed the box around. He then produced a bag of Hershey Kisses, giving each of us a few to top off our pudding. “Enjoy gentlemen,” he said and we all dug in.

As we sat there in the cold November night, talking, laughing, eating our chocolate enhanced pudding cups, I became very aware of everything around me. I sat there quietly for a few moments and just soaked up the experience; the chill in the air, the yellowish lights of the rec yard, the creamy texture of the pudding and the heavenly taste of chocolate. I listened to my friends, really listened. And understood. I was enjoying this moment, everything about it.

I was… content. Sitting there in the cold, in prison, eating pudding out of a can, I was so content. I’d forgotten what it felt like. How long had it been since I truly felt content?

Maybe it was that snowy day years ago, when my sons were still in grade school. I took the day off from work and took them sledding on a small hill by their school. We’d pile onto the sled, me on the bottom, my oldest son next, the youngest on top; then zip down the hill, across the snow-packed basketball court onto the icy sidewalk, right up to the entrance of the school. The boys would laugh loudly, their noses all runny, their cheeks rosy red. We’d trudge back up the hill and repeat the run, over and over, for hours. An incredibly joyous day. True bliss.

Since that night of the secret Buddhist Decadent Dessert Rite, I’ve experienced other moments of contentment: an expansive North Carolina sunset, a cup of cappuccino while listening to Morning Edition on NPR (Yes, we have cappuccino in prison, but no Starbucks as yet), sitting around at the end of the day with my cellies sharing this surreal experience that is prison. Glimpses of contentment; I can’t seem to sustain it for long, but it’s a start. And I figure if I can be content here in this repressive place of shattered lives and hopes, what will it be like out there, beyond the fences.

I still have so much to learn, to experience. Patience for example. Being a baby boomer, I‘m a product of our Veruca culture. Remember Veruca, the snotty, spoiled rich girl from Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory? Her mantra was “I want it now, Daddy.” That was me—well still is me to a great extent. I have however, given up my goal of becoming fully enlightened before August 15, 2007, the date I’m eligible to go to a halfway house. That may have been an unrealistic goal, I now realize. But, I’m okay with that. I’m learning, progressing.

True compassion for all sentient beings is something else I’m practicing. I volunteer in the hospice program here and visit terminally ill cancer patients. Oh, I’d volunteered in my old life for all the wrong reasons; mostly so I could feel better about myself. Plus it always looked good on the old resume. But, imagine the suffering of being terminally ill and being confined in prison, far from family and friends. Think of it, knowing you will die in prison.

Lama Zopa Rinpoche spoke of how, for the monks and lay people of Tibet, prison was like a hermitage—a place where they could enrich their lives with many realizations. He was right. This was the place where I had to come. I needed this time to finally learn and realize that happiness isn’t someplace out there in the hazy distance. It’s not the next promotion, the bigger house, the red convertible sports car. It’s not all the stuff. Happiness is here now, all around us. It’s cherishing every moment of life, all of it—the good and the bad. Bliss is a state of mind we can all cultivate by following the Buddha’s way.

So, I’ll continue my trek down the path, singing Dancing Queen all along the way.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.