The chain of miserliness

A Crown Ornament for the Wise, a hymn to Tara composed by the First Dalai Lama, requests protection from the eight dangers. These talks were given after the White Tara Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2011.

- We need to acknowledge the reality of our situation in cyclic existence

- How we tend to think that samsara is not so bad

- Renunciation is the first of the three principal aspects of the path

- The initial lamrim meditations are crucial for changing our perspective

The Eight Dangers 12: The chain of miserliness, part 1 (download)

In our teachings about Tara we’ve done the lion of pride, the elephant of ignorance, the fire of anger, the snake of jealousy, the thieves of distorted or wrong views. Now we’re on the chains of miserliness.

Binding embodied beings in the unbearable prison

Of cyclic existence with no freedom,

It locks them in craving’s tight embrace:

The chain of miserliness—please protect us from this danger!

“Binding embodied beings in the unbearable prison of cyclic existence with no freedom.” That’s heavy duty, isn’t it? And that’s our situation. And that’s what we really have to acknowledge in order to get anywhere in our practice, is that we’re bound in cyclic existence with no freedom. But that’s not our usual assessment of our situation, is it? We’re usually like:

“What’s cyclic existence?”

“I have no idea.”

“Why am I alive?”

“Well I never thought of it.”

“What’s the purpose of my life?”

“I haven’t thought about that either.”

“What happens after death?”

“I don’t want to think about that; it’s too scary.”

Normal situation, isn’t it? What’s the purpose of my life? Eat, drink and be merry. Sex, drugs, and rock and roll. And so most people just live on automatic.

One of the first things in our Dharma practice is to actually look at the situation in which we live. And even when we’ve been practicing Dharma for a long time that can be very difficult because our usual view is, “Well yes there’s samsara, but as long as I have a good life and I’m comfortable and people like me, a little bit of suffering’s okay, but not too much and, you know, my life’s pretty good. What are you talking about being bound in the unbearable prison of cyclic existence? I’m not in an unbearable prison. My life is good. I’ve lots of freedom. I can burn the Koran if I want to.” It’s the wrong kind of freedom. “I can say anything I want, I can do anything I want. I can have anything I want. I’m not in an unbearable prison. Okay, sometimes there are problems, but they’re all other people’s fault. There’s nothing much I can do, so I’ll just enjoy.” Isn’t it? And even when we’ve been practicing Dharma for a while, you know, our usual view is, “Well, you know, just live day by day, and try and avoid suffering, have happiness and say a few mantra and that’s good enough.”

But when we’re thinking about the three principle aspects of the path, renunciation and the determination to be free is the first one. So to really start feeling what Dharma’s about, we have to have some understanding of cyclic existence and how we’re trapped in it by our ignorance, anger, attachment. And now it’s pointing out miserliness; how miserliness traps us.

We have to really develop a new self-image of being somebody in cyclic existence who was born here due to ignorance, anger and attachment, who thinks they’re truly existent, when in fact they exist by being merely imputed, yes, who just wants happiness and not suffering, but doesn’t look around them to see what the situation of other people is and to see how our actions affect others, yes? So we have to change this self-image of how we think of ourselves, you know? We don’t think of ourselves as somebody who could die today, do we? You know, we hear lots of teachings on death and impermanence again and again but, you know, that’s for other people. And yes, one day I’ll die but, you know, I’ll have it all planned out, easy and the perfect death. Right! Okay?

These initial meditations on the gradual path to enlightenment, on the stages of the path to enlightenment, are crucial for changing that image of who we are and what our situation is. And when we’ve done that, then these verses really make sense. But until we’ve done that, miserliness isn’t really a problem, is it? The more I keep for myself, the more I have. Yippee! And I don’t want to look miserly, so I give enough so that I don’t look like a cheapskate. But only enough so that I don’t look like a cheapskate. We don’t see miserliness and craving as a problem.

We have to kind of go back and really think about what cyclic existence means, and what the meaning of our life is and want to get out of this situation and how to go about doing it, okay? We’ll continue with miserliness tomorrow.

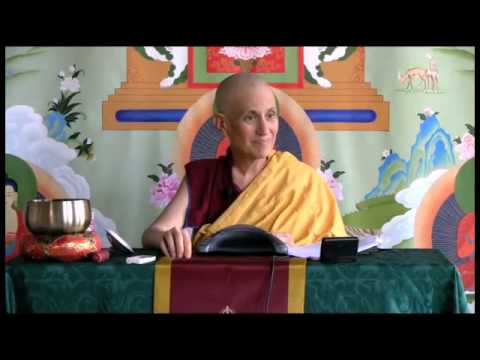

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.