Impermanence, dukkha and selflessness

Part of a series of teachings from a three-day retreat on the four seals of Buddhism and the Heart Sutra held at Sravasti Abbey from September 5-7, 2009.

- How we come to understand impermanence

- How permanence, when not examined closely, seems acceptable

- Things beyond our understanding, and what leads us out of suffering

- The three kinds of dukkha

The four seals of Buddhism 02 (download)

Questions and answers on the first seal

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Comments from your discussion group, or questions?

Audience: We were talking and it seems like from the talk you gave this morning, you were talking about really being able to deeply think about impermanence and realize it and everything. So the question for me was, if you really deeply understand impermanence doesn’t that lead to understanding dependent arising? And does that mean you have to have a realization of emptiness to deeply and correctly understand impermanence?

VTC: You’re saying to understand impermanence deeply, don’t you have to understand dependent arising and emptiness? Actually the realization of subtle impermanence comes first. Of course understanding dependent arising, especially dependent arising in terms of causes and conditions, is very important for understanding impermanence. But the understanding of dependent arising in terms of dependent designation—things being imputed merely by mind—that isn’t necessary in order to realize impermanence.

However, the realization of emptiness is related to the realization of impermanence in the sense that if things were inherently existent that would mean that they would be independent. This means they don’t rely on any other factors—which would mean that compounded things, composites, produced phenomena would be permanent because something that’s permanent doesn’t rely on causes and conditions. It just exists by its own nature. This is one of the contradictions that comes about if you accept inherent existence. For example, the glasses, you would say the glasses are permanent because they’re inherently existent. You would throw that consequence at somebody who knows the glasses are impermanent but he thinks that they exist inherently. So, “Oh yes, glasses are inherently existent. But no, they’re not permanent. You can’t say they’re permanent.” But then they begin to think about it and then they realize that if things are inherently existent they would have to be permanent.

Other questions?

Audience: You were talking about the electron; and it’s easy for me to think that an electron moves from here to here, and it inherently exists.

VTC: They just changed places, yes.

Audience: Is there a discussion about impermanence in the sense of moving through time? It seems as though the only difference is that it’s half a second older than it was prior. So because some things don’t, well, maybe on a molecular level they change. I don’t know but it would seem that some things don’t seem to change very much except for that maybe they age.

VTC: You said, we were talking about the atoms and the electrons and it seems like, here’s your electron that’s solid and it just moves from here to here. And so it seems like some things, you know, you’re asking if there’s a discussion of impermanence in terms of time because it seems like things kind of remain the same, it’s just that they age.

Audience: Yes, essentially that maybe there are things that don’t seem to change physically except that at some point they’re older than they were before?

VTC: Yes. They don’t seem to change physically but they’re older than they were before. Actually this is showing subtle impermanence because something that is arising is already ceasing. On a gross level this cup looks the same as it did this morning and so our mind thinks, “Oh, it’s permanent.” But if you actually think about it, the cup can’t be permanent. If it were it couldn’t have been constructed, it couldn’t break. And the fact that eventually it’s going to disintegrate in one way or another is because moment by moment, you know each moment it exists it’s already ceasing and going out of existence. Although to our gross senses something may look the same, that doesn’t mean it is the same.

Like us, we look kind of the same as we did this morning, just as old as we did this morning. But then we’re so surprised sometimes we look in the mirror and, “Oh, I look so old!” How did that happen? Did it just happen overnight? Well no, it didn’t happen overnight. It’s because each split second the body is arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing; so these subtle changes are occurring constantly and just accumulated over time. Then our gross senses begin to notice them. We can’t always trust our gross senses. They don’t perceive the reality of things.

Audience: I asked this because it actually seems, well if you really think about it then it doesn’t seem to work so well. But it seems quite acceptable that there’s a creator god that’s able to create and stay permanent at the same time. If you think about it, it doesn’t really work. But if you just kind of look at it, it’s quite acceptable.

VTC: Yes, right. And that’s the thing, that many things on the unexamined level seem quite acceptable. There’s a permanent absolute creator that doesn’t change, yet creates. If you grow up being taught that idea and you’ve never investigated, it seems to make perfect sense. But as soon as you start to investigate it using analysis, you see that it doesn’t work.

In the same way, hundreds of years ago, it seemed perfectly reasonable that the rest of the universe circled around the earth. That’s the way it looks like to our gross senses, doesn’t it? The sun circumambulates the earth. We’re the center of the universe. Everything revolves around us. It wasn’t until people began to actually analyze that they found, no, things don’t exist that way.

So just on the level of making assumptions based on appearances, that’s very risky. That’s why the Dharma path is really about investigation and examination and analysis. Not just about assumptions and undiscriminating belief. Sometimes when we investigate and analyze, things exist totally opposite than we thought they did before. But we have to be courageous and do that and be willing to throw out our wrong assumptions because they don’t hold up to analysis and wisdom.

Audience: So is there nothing beyond our understanding? Because history would suggest there are things beyond humans’ understanding—until they understand them. The earth was flat for centuries and people thought that if they went far enough they’d fall off the end.

VTC: He asked if there is anything beyond human understanding. Yes. I sure hope so because we don’t know very much, and we don’t understand very much, and just because people used to think the world was flat, that did not make it flat. It wasn’t that the world was once flat and it became round once Galileo had this theory. This is actually a good example because when we get into the refutation of emptiness you might think, “Oh, things used to be inherently existent, but once we analyze we make them empty of inherent existence,” and no, we don’t. We’re just realizing what the reality is—because our human mind is quite limited. It’s very vast in one way and it has a lot of potential, but it’s also quite limited and full of wrong conceptions due to our ignorance.

Audience: Perhaps the creator is just beyond our understanding.

VTC: Is the creator beyond our understanding? We have to have some standard, don’t we? Otherwise we can invent all sorts of theories and just say they’re beyond our understanding. I could make up a lot of different theories and say—actually so many people do and they market them and say, “It’s the esoteric teaching that is beyond your understanding.” There’s no way to use your intelligence if you just say it’s all like that.

We have to rely on reasoning. We have to rely on what stands up to reasoning and what doesn’t. Otherwise we have no way of ascertaining anything. Because we could just say anything and say it’s true because I said it. Which is very often how we operate, isn’t it. “It’s my idea, therefore it’s the right one.” That’s not very reasonable, is it?

Audience: I think the point or the center of all this is: What’s beneficial and what isn’t. There very well could be a creator that’s beyond our understanding, but how does that help us get out of suffering?

VTC: You’re saying that analysis isn’t actually the standard but benefit is. You’re saying that there could be a creator that’s beyond our understanding, but how does that help us get out of suffering?

Actually, from the viewpoint of a number of people that does help them get out of suffering. That’s why we respect all the different religions, even though we may debate with some of their theses and some of their beliefs. We still respect them because they can benefit the people who believe in them.

But just because people believe something doesn’t make it existent. Otherwise I could say Santa Claus exists and he’s beyond our understanding, and the tooth fairy, and the boogey man, and they all exist and are beyond our understanding. Can any of you understand the tooth fairy? We’re still praying that as we get old and our teeth fall out, we’re praying for the tooth fairy to come because we need some more money. I’m at the dentist. I had an extraction. Put it under my pillow. If the tooth fairy didn’t show up, he’s definitely beyond my understanding.

Audience: Is it true that as we gain wisdom and become enlightened, then nothing will be beyond our understanding? But then we won’t be in human form. Right now things are beyond our understanding, but when enlightened, then nothing is?

VTC: Well, so you’re asking, at what point do things become within our understanding? Actually as human beings, we have the potential to have this kind of understanding of everything. It’s just that the ignorance blocks it. So we try and use our potential to refute what ignorance believes as true. By disproving what ignorance is grasping at we come to actually understand what does exist, and also what doesn’t exist. So we have that potential as human beings.

Audience: In our group as we discussed the experience and our understanding of impermanence, it seemed like it often came back around and what made it difficult was our sense of the permanent substantial self. The understanding or the integration of impermanence met this roadblock. Even though we had this concept of, “We’re not solid and exist” but we still have that sense of I. It seemed to get in the way of that experiential understanding of impermanence because it was based on still having that sense of me.

VTC: So you’re saying in your group where the roadblock came, people could understand how things are impermanent, but there’s this feeling of an I that’s just there, that doesn’t change, like some kind of soul maybe.

Audience: We understand that our bodies change and die, but there’s still that sense of me, I.

VTC: But I’m still me. My body changes and dies but I’m still me. There’s some kind of permanent soul, permanent self. This is one of the things when we come to the third of the four seals—empty and selfless—that we’ll talk about. This is very much an idea that many of us grew up with and is taught in theistic religions, that there is a soul or a self that is permanent, unitary, and independent of causes and conditions. This is a belief. This is something that they say is artificial. It’s not even innate. But it’s an idea that we created that there’s a permanent me that is single, unitary, monolithic, and doesn’t depend on causes and conditions.

So there’s the soul and my body can follow and my body’s going to disintegrate, but there’s still me that hasn’t changed. Even as I’m living in this life, my body changes and ages, my mind changes, my emotion changes—but there’s still something that’s the essence of me-ness, that totally doesn’t change.

We grew up with this kind of idea, so it’s in there somewhere and we hold on to it. It’s a grosser form of grasping. Grasping at inherent existence is actually much more subtle. But this gross one, of a permanent, partless, independent self—many religions are founded on this. Many philosophies are founded on this. Also it’s an idea that emotionally feels very secure.

When we’re faced with the idea that not only our body disintegrates but our consciousness disintegrates, then who are we? That means that, “I’m going to disintegrate.” That’s scary. So what do we do to prevent ourselves from fear? We make up a theory that there’s a permanent, partless, independent me; and emotionally it’s very consoling. But it’s not true.

We also have to look at this: Just because something is emotionally consoling doesn’t mean it’s true. For example, at the time of the Buddha, King Bimbisara was one of the Buddha’s patrons. He had a son Ajatasatu who very much craved to have the throne. He imprisoned his father and then killed his father and usurped the throne. Later Prince Ajatasatu, now King Ajatasatu, felt great regret for having killed his father. He was just so tormented—and he had also killed his mother. He had imprisoned his mother and also killed her. He didn’t want anybody messing with his claim to the throne. He felt so much regret afterwards that he became so depressed he couldn’t function. So the Buddha said to him at that time, “It’s good to kill your mother and father.”

The Buddha did this as a way of skillful speech to alleviate the guilt that he was feeling. But what the Buddha was really meaning when he said it’s good to kill your mother and father, was of the 12 links of dependent origination, craving and grasping. Or sometimes they say craving and existence, the eighth and ninth link. Or sometimes they say the eighth and tenth link, these are the “mother and father” of rebirth, and it’s good to kill those. That’s what the Buddha really meant when he said, “It’s good to kill your mother and father.” But to emotionally console Ajatasatu at that moment he said that. Then later Buddha led him on the path so he could free himself of those two links of dependent arising that produce rebirth.

The Buddha was very skillful. It’s not true that it’s good to kill your mother and father. It’s actually two of the most horrible actions we can do, but he said this for a specific reason in a specific context there. Okay? So we always have to check things and just not take everything literally, but see what the context was, see what the intention was, see what the meaning was.

Audience: When we talked about the realization of subtle impermanence, would that be a direct perception?

VTC: Yes. The realization of subtle impermanence is a direct perception of subtle impermanence. Or I should say, you could have an intellectual or an inferential realization of subtle impermanence but the actual realization you’re striving for is a direct realization of subtle impermanence.

Audience: It’s hard for me to fathom how that works. I can see how you could have inferential understanding. But your senses can’t help. Like if you look at that cup for it to change, but in my lifetime I might not see a change, so how could I have a direct perception?

VTC: Okay, so how could we have a direct perception if our eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and tactile sensation can only detect gross impermanence? That’s because there’s the mental sense. So these realizations of subtle impermanence, of emptiness, all the Dharma realizations are not done by the sense consciousnesses. They’re done by the mental consciousness. It’s called a form of yogic direct perception.

Audience: Okay, so it is not what you’re seeing, it’s what you’re realizing. I can understand the words…

VTC: What you’re realizing is, as you develop very strong samādhi, the mind gets more and more refined and able to see things in finer and finer increments of time because the mind is so focused and concentrated. So when you have very strong mindfulness, very strong concentration and then you know you should be looking at how things change, then you can see their very instantaneous arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing, arising—by the power of the mind, by the power of yogic direct perception. So that happens in meditation.

Audience: It would seem that’s a little bit like when things seem like they’re happening in slow motion—like if you’re in a car accident. One time I was in a car accident and for a brief moment it seemed like everything slowed down.

VTC: Yes, I’ve heard people say that. Like right before there’s a car accident, it feels like time’s going very slowly. I don’t know. I haven’t realized subtle impermanence. I don’t know if you would actually see things like that because going very slowly isn’t necessarily seeing things arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing.

Audience: When you’re saying, seeing things, at this point are you talking about more like experiencing them?

VTC: Yes. I’m talking about with your mental consciousness. When I say seeing I’m referring to your mental consciousness—with your wisdom. With your wisdom you’re able to see things change in very small increments of time, with your wisdom, with your very deep samādhi, very strong mindfulness.

This is why we have to develop ourselves in meditation practice because these insights are not something that our senses can have. In fact our senses distract us from gaining these insights. Instead we have to develop the power of the mind, the mental consciousness.

Audience: Is it true that wisdom as developed in the power of the mind can actually influence what the senses perceive? So for instance, you hear stories about highly realized practitioners having clairvoyant powers, and that maybe they’re hearing things from far away and so…

VTC: Okay, so you’re asking can the power of the mind seem to influence the senses? We do talk about different supernormal powers. The ability to, let’s say, hear things at a very far distance, the ability to see things in the past, or to see things in the far distance. But that seeing is not done with the eye. That hearing is not done with the ear. That is done with the mental consciousness.

This gives you some idea of how powerful the mind is. Then you see in the day-to-day life how we neglect our mental consciousness. We’re so hooked by sense consciousness. We say, “Oh, that’s beautiful,” “Oh, that’s ugly,” “Oh, I want that,” “Oh, I don’t want that.” There’s so much outward gazing through what we see and hear and smell and taste and touch—so much craving the sense experiences and ignoring the mind. Yet it’s the mental consciousness that actually is the one that develops wisdom, that develops samādhi and concentration, and that develops mindfulness.

All of this is done with the mental consciousness not with the sense consciousnesses. So it means for us to progress we’ve got to start to turn inward some more. Let go of some of this distraction that we’re constantly involved in with our senses—so that we can tap into and develop our potential.

Audience: In developing the mental consciousness, so this is a practice question. When you practice is it a good idea to, like, I’ll give you an example. I’m auditory so I like saying things out loud. Is it a good idea to try to just mentally, you know, without using words…

VTC: Okay, so you’re asking, what’s the role of the five senses in learning the Dharma? Well, we initially take in the Dharma information through reading, and hearing, and things like that. Some people learn better when they see. Some people learn better when they hear. Some people learn better when they do, when they touch. So whatever sense helps you learn the Dharma best, you can use that sense. But the thinking and contemplating about the Dharma is done with the mental consciousness. If you learn things better by sound, then it’s helpful to recite things out loud because they stick in your mind better. Then when you’re meditating too, then you can remember them and say them again to yourself and contemplate them. Then some people learn better by reading and so they can emphasize that and then when they meditate they can reflect on what they’ve read. It’s the same with kinesthetic, with doing things.

Audience: But are you trying to get rid of the dependence on them?

VTC: Are you trying to get rid of your dependence on seeing and hearing? Our senses, the seeing, the hearing, these things can be useful for learning the Dharma and we should use them for learning the Dharma. If we don’t, then we have no way of learning the Dharma. As you progress and your understanding deepens, then you naturally become less dependent because the understanding and the wisdom are growing in your mental consciousness. Okay? But use the senses. That’s what we have to learn with when we’re learning the Dharma.

What we don’t want to do is be distracted by the senses. I’m sitting here and I’m reading my Dharma thing and I look up and, “Oh, look at that mountain range over there. It’s so gorgeous.” You know? And then the time goes by and the mountain range is arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing. My mental consciousness is arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing, but my mind is thinking it’s all permanent and it’s there for me to enjoy and cling onto. Then when they go and they cut the trees down from the mountain I get upset.

Audience: I have a question that I questioned. It relates to what you were just saying in talking about being in school and all these forms of knowledge to grasp onto. And how contemplating impermanence helps look at, well what kind of knowledge is really lasting and useful and what kind of isn’t so important. So I was thinking a little more, because right now I’m in school. There are things that I have to study that aren’t Dharma. So I can work on my motivation for why I’m studying those things. Maybe I’ll be able to use some of that eventually in some ways that support the Dharma but I was wondering, how does that work? What my mind is engaged in is still not Dharma, how does the motivation affect that action?

VTC: You’re saying that when you think about impermanence and then you think about the topics you’re learning in school, then it kind of makes you have some doubt about the value of what you’re learning. But you know that you can transform that into a Dharma action by changing your motivation and by thinking, you know, “I’m going to learn this material and then I’ll use it to benefit sentient beings.” But then you said, “But the material itself is not explicitly the Dharma, so then how does that work?” What are you studying?

Audience: Sustainable agriculture.

VTC: Oh, excellent! Sustainable agriculture. Chandrakirti talks about seeds and sprouts all the time. Nagarjuna loves seeds and sprouts. They are the analogy we always use for dependent arising and especially for dependent production, that things aren’t produced from themselves, they aren’t produced from other, from both, from neither. So you can learn your sustainable agriculture. You can learn that with a good motivation to benefit others. Then also you can stand back and reflect and say, “Well, what’s the real nature of these seeds and sprouts? What’s the substantial cause? What are the cooperative conditions? How do things arise? At what point does the seed become a sprout? Think about the seed ceasing at the same time the sprout is arising. But if the sprout is arising, does that mean it already exists? If it already exists, how can it be arising? You can bring in a lot of these concepts about dependent arising and emptiness. Just reflecting on the sustainable agriculture that you’re studying—and seeds and sprouts are really a good way.

Audience: Have we got time to go back? I want to learn more about this, the “I.” The impermanence of the “I.”

VTC: The impermanence of the self. Yes.

We’ve been talking about the impermanence of physical objects. But one of the big things is that we can talk about the impermanence of the mind—because we can see our mind changing moment by moment. Then because the self, the I, is dependent on the body and mind—the I, it doesn’t exist apart from the body and mind. Does it? Can you have your body and mind here and your self over there? When you say “I,” doesn’t that in some way refer to your body and mind, or mind? When you say, “I’m walking.” What’s walking? The body. “I’m thinking.” “I’m eating.” “I’m feeling happy.”

Whenever we say “I” and the I is doing something, it’s always in relation to the body or the mind. If you take the mind and body away, can you have the I somewhere? That’s that permanent one that you want, that soul that’s separate from the body and mind that’s still there. When you really analyze, can you have a person, can you have a self separate from the body and mind that doesn‘t depend on the body and mind? Put it this way, can you show me a person that doesn’t have a body and mind?

Audience: When you die the body and the mind stays, and then if there’s something that continues, what is that?

VTC: The body stays but the mind isn’t made of molecules. Mind doesn’t stay here after death. The mind continues on. In dependence upon that continuity of mind, we give the label “I” and we say “so-and-so” is reborn.

Audience: So it’s the mind that’s reborn?

VTC: Yes.

Audience: So the mind is the soul? We found it! [laughter]

VTC: No. When we talk about the mind, the mind doesn’t mean the brain because the brain’s the physical organ. The mind doesn’t just mean the intellect. The mind means every part of us that cognizes, perceives, experiences—that is conscious. All of that is subsumed under the word “mind.” From the Buddhist perspective there is no spirit or soul. There’s just the body and the mind and in dependence on that we label “person.” The mind has very gross levels like our sense consciousnesses. It has very subtle levels like our mind at the time of death. But it’s all the mind in the sense of being clear and knowing.

Audience: It’s not permanent because it’s changing all the time from life to life, from moment to moment?

VTC: Exactly. Yes. The mind is impermanent, always changing. It’s the base upon which we label “I”—the body and mind. If both of these are constantly changing moment by moment, arising and ceasing, then how can the self that is labeled in dependence upon them be permanent? It can’t be. And if you’re permanent you can’t become a Buddha. Think about that. If we had a permanent soul we could never become a Buddha, could we? Permanence also works in our favor. It’s because things are impermanent that our mind can change. We can gain new knowledge, new insight, new wisdom. We can cultivate bodhicitta. We can enhance love and compassion. It’s because of impermanence that all these factors can be increased and enhanced. Whereas if our mind were totally permanent there’s no way we could ever change. We would always be stuck. Permanent means it doesn’t change from moment to moment.

Audience: So when you die the mind continues … [inaudible]

VTC: Yes. Right. Impermanent means from moment to moment it changes. Eternal means it lasts forever.

Audience: I get confused too. Sometimes for me it seems like a matter of semantics; that the mind is going from body to body or whatever. But I could see the soul as, I mean, using it just as a matter of using terminology that like some people use the soul and spirit in the same way.

VTC: Okay. So you’re saying we talk about the mind continuing on and couldn’t we just say soul continues on? Well, what we mean by mind and what we mean by soul are very different. The mind cognizes. The mind arises and ceases each moment. The mind is a dependent phenomena. It depends on causes and conditions. It depends on parts. It depends on being labeled.

The soul does not change. It’s there, static. It’s not affected by other phenomena. It, in turn, cannot affect other phenomena. Something that is permanent is beyond causes and conditions. That means whatever you practice, whatever you do, if there is a soul, it cannot change. It also would mean that the soul would not arise dependent on causes and conditions. So it would even be contradictory to say that God created it because God would be a cause—and something that’s permanent does not depend on causes. Something that’s permanent is unaffected by causes.

So it’s not a question of semantics. It’s not just saying, “The mind continues on, the soul continues on, the spirit continues on—it all means the same.” No. Those words refer to very different things. The mind exists, but a permanent soul does not exist. And a spirit that’s separate from the body and mind? That is kind of a new age version of a soul. Show it to me. If it exists, what is it?

Audience: So just in summary, there really is nothing that is permanent.

VTC: So is there anything that’s permanent? Of the phenomenal world, of things that are composites, that are produced, none of them are permanent. However, there are permanent phenomena. There are things that do not change. Here we have to get into the whole idea of conception—and negations, positive phenomena vs. negations. So in negations, things are not X, Y and Z. Those negations are permanent in that they’re created by concept. Actually emptiness, the lack of inherent existence, emptiness itself is permanent. It doesn’t change. It’s the ultimate nature of phenomena. But it’s a negation. It’s the lack of inherent existence. It’s not some kind of positive substance.

Don’t let your mind that wants to believe in a soul turn emptiness into some kind of positive cosmic energy out of which everything is created—because it’s not. Emptiness is a negation. It’s what we call in philosophy a non-affirming negation or non-affirming negative. It’s just negating inherent existence and it’s not affirming anything. So emptiness is not some kind of universal, cosmic substance out of which everything comes—although you guys sure would like to believe.

This was actually one of the ancient Indian views. The Samkhya view was that there was this primal substance. Out of it the whole phenomena emerged. And liberation was that everything dissolves back into it.

But then, you know, if there’s a universal consciousness or universal cosmic substance, you run into that same thing of: Is it permanent? Is it impermanent? How does it create? You run into those same difficulties.

Audience: Two questions. The first one’s quick. Is impermanence permanent?

VTC: No. Impermanence is also impermanent.

Audience: So it’s not a negation?

VTC: No.

Audience: And then my other question was, you said a few minutes ago that it’s comforting to have this idea of permanence—so we come up with this idea of permanence to kind of protect ourselves. But it seems kind of natural to think that we’re permanent in my experience. I’ve never grown up with a religious view that taught specifically that you inherently exist. So it seems quite normal to feel as though I’m the same person that I was when I woke up this morning. I haven’t changed. I haven’t gone through, of course, I’ve done things but essentially inside I’m the same person. It doesn’t seem to me, although it may have happened at a subconscious level long ago, but it doesn’t seem to me that that was a concept that I came up with.

VTC: So you’re saying that it just seems rather natural to have the feeling that, “I’m the same person I was this morning,” that it wasn’t that anybody taught you that, but that you just feel, “Well, I’m the same person that I was this morning.” There is that part of us that feels I’m the same person that I am this morning. But there’s also another part that we also naturally feel that I’m different than I was this morning. This morning I had a stomach ache and now I don’t. So there’s also the natural feeling of the self that changes.

Audience: This seems more like that sense that is experiencing different things which again I think of as being the mind but we tend to think of it as more than that; like it’s kind of our essence.

VTC: So you’re saying that in terms of experiencing things, so we feel like, “There’s me—solid, permanent, unchanging—here. And I just experience different things and that’s what it feels like. But there’s really this thing that doesn’t change.” So there is that feeling sometimes. But then on the other hand we say, “This morning I was in a good mood but now I’m in a bad mood.” So then we do have this other sensation that, “Well yes, I did change.”

The point is we have a lot of contradictory sensations and thoughts. That’s the point. Our mind is full of contradictory things. Because there’s this feeling sometimes, “Yes, it’s just me. I contact all these different sense objects but I don’t change.” But then the next moment we’ll say, “I listened to that loud music and now I have a headache.” It means I changed. I didn’t have a headache before I listened to the music. The music affected me and, “Now I’m different.”

We have all these different kind of notions.But the thing is we’ve hardly ever examined them to see which ones are actually realistic and which ones are not. In the same way that we say, “You made me mad,” and we never examine that. “I’m mad. You made me mad.” We never examine it. But if we start to examine it we’ll realize, “No, the other person didn’t make us mad.”

The title of a book I’m going to write someday is Don’t Believe Everything You Think.

Audience: I think there’s a bumper sticker like that. They stole your idea.

VTC: They stole my idea. Wouldn’t you know it?

The second seal: All polluted phenomena are in the nature of dukkha

Okay, so we move on to the second point. You’re going to like the second one more. The second point is that all polluted phenomena are by nature dukkha, or unsatisfactory. All polluted phenomena are unsatisfactory. Sometimes the word polluted is translated as contaminated or tainted. Both of these words can be misconstrued. The idea is when we say something’s polluted, what is it polluted by? The ignorance that’s grasping at true existence. So any phenomena that is polluted by ignorance is in the nature of dukkha. It by nature is unsatisfactory.

Sometimes you’ll hear it’s by nature suffering. Here’s where we see that the word suffering is not a good translation for the word dukkha—that it’s very limited. If we say this book is by nature suffering that doesn’t make any sense, does it? That book is not suffering and this book does not have to make me suffer. In fact I read it and it makes me happy. So you see that suffering here does not mean pain. Dukkha does not mean pain.

Three types of dukkha

We talk about three types of dukkha. One is the “dukkha of pain.” That kind of dukkha is something that all living beings recognize as unsatisfactory. Even the insects, the animals, the hell beings, the gods, everybody recognizes pain as unsatisfactory. You don’t need a degree for that.

Then the second kind of dukkha is called the “dukkha of change.” This refers to what we normally call pleasure or happiness. It’s called dukkha or unsatisfactory in that whatever pleasure and happiness we have does not last. It changes. It goes away. Not only does it change and go away but even while we’re experiencing it, although we call it happiness, what we’re calling happiness is actually a low grade of suffering.

For example, when you’re sitting here and your knees start to ache, and your knees ache and your knees ache and you’re saying, “When is this session going to be over? This nun doesn’t shut up. She keeps talking and my knees hurt. I want to stand up.” So finally we dedicate, we stand up, and the moment you stand up you feel, “Oh what pleasure”—and you feel real happy. Now if you continue to stand there—and you stand, and you stand, and you stand, and you stand, what happens? Then it’s like, “I want to sit down. I’ve been standing in line waiting at the counter for so long. I just want to sit down.” So we have to look at: If standing were in the nature of happiness, the more we did it the happier we should be. But we only call it happiness when we first do it because the suffering of standing is still small, but the pain of sitting has been eliminated, so we call that happiness or pleasure. The more we stand the more painful it becomes, and then we long to sit down. When we first sit down it’s like, “Ah.” So it’s pleasure. But that’s just because the suffering of sitting is small and the suffering of standing has gone away temporarily.

If we look at anything that we call pleasurable that we experience with this mind under the influence of ignorance, none of it really is inherently, in and of itself, something pleasurable. For example, let’s take eating. If you’re dreaming about medicine meal right now, “Oh, medicine meal. I wonder what they’re having. Soup! It’s the same soup we’ve been eating for the last week, for the last month, the last year. It always looks the same. Every time I come to visit Sravasti Abbey, it’s the same soup.”

Imagine that you’re really hungry. So you really want the soup. You sit down. You’re so hungry. You get the soup. You start eating and it’s so good, “Oh what good soup!” And you continue eating, and you continue eating, and you continue eating, and you continue eating, and what happens? You have a belly ache, don’t you?

If eating were in the nature of pleasure, the more you ate the happier you should be. But it’s not. It’s pleasure at the beginning because the suffering of hunger has gone, or the suffering of boredom is gone, and you get the immediate pleasure. But the more you eat? It, in and of itself, is not pleasurable. When we say “All the contaminated things are unsatisfactory,” this is another meaning. It refers to the second kind of dukkha.

Then the third kind of dukkha is called “pervasive conditioning” or “pervasive conditioned dukkha.” What this means is just being born with a body and mind that are under the influence of afflictions and karma. Regarding afflictions: The root affliction is the self-grasping ignorance. It gives rise to attachment and anger and jealousy and pride and resentment and all these other things. So just having a body and mind that are under the influence of afflictions and karma, that’s the third kind of dukkha.

We may be sitting here having kind of a neutral feeling: nothing’s particularly good, nothing’s particularly bad. We may have a happy feeling—we just won the lottery, or got a new boyfriend, got the job you wanted, or whatever it is. You’re really happy. But there’s no security in that because all it takes is just the slightest change of any condition and the happiness crumbles or the neutral feeling changes into pain. Why? This is because our body and mind are under the influence of afflictions and karma.

The root affliction is ignorance that grasps at things as having true or inherent existence. It means that it grasps at things as being completely independent from any other factor—that ignorance. Because we apprehend our self as inherently existent and we apprehend our body and mind and external phenomena as inherently existent, then we think there are real solid things. “There’s a real me here. There’s a real outer world there.” Then we get attached to things, “I want this. I want that. I want the other thing.” This is because this big inherently existent “I” always needs, always wants, is always seeking for pleasure. Then with the attachment—when we don’t get what we want, when we don’t get what we’re craving for—then we have pain. So whatever interferes with our happiness, we have hatred and anger towards them or it. Then of course, when we have more happiness than somebody else, we’re arrogant. When they have more happiness than us, we’re jealous. When we’re too lazy to care about anything, we’re lazy.

So we have all these afflictions, and then the afflictions produce actions. Motivated by these different mental afflictions then we act in different ways. Under the influence of attachment we may lie to get what we want, steal or cheat to get what we want. Under the influence of anger we harm others verbally, we harm them physically. Why? This is because we’re upset because our happiness has been interfered with. Under the influence of confusion, we just space out on drugs and alcohol and think that’s going to calm us down.

Having the body and mind under the influence of afflictions and karma produces actions. The actions or karma leave karmic seeds on our mindstream. At the time of death when those karmic seeds ripen? When they ripen they’re together with minds of craving and grasping, wanting another existence in samsara, and that pushes our mind into seeking another rebirth. So that karma starts ripening, that’s the link of existence in the twelve links of dependent arising, and boom—birth happens. We’re reborn into another existence. This is what they mean by cyclic existence under the influence of karma and afflictions, is that continuously the body and mind are under those afflictions and karma. And especially the mind, at the time of death when strong afflictions arise and some karma ripens, then boom, there we go into the next rebirth. Then we experience all of these three types of dukkha again in the next rebirth—of pain, of change, of pervasive conditioned existence.

Even if you’re born in these very high realms of sense pleasure deluxe, maybe you don’t have painful feelings but you still have the dukkha of change and pervasive conditioned dukkha. Even if you’re born in states of samādhi where you’re just in this single-pointed concentration of bliss for eons, you don’t experience pain and you don’t experience ordinary pleasure. But the body and mind are still under the influence of ignorance, afflictions, and karma. When that karma ends, then you take a lower rebirth again. This is what we’re talking about as samsara, as cyclic existence. When you hear about it, if you have this feeling of, “Yuck!”—that’s good. We want to feel about this—“Yuck! I don’t like this. I want to be free of this.” We want to feel that. It’s like an inmate in prison. If the inmate thinks that the prison is fairyland, they’re not going to try to get out. But if you really think that your prison is hell, then you’re going to have some energy and impetus to get out.

So when you hear this discussion of what cyclic existence is, what samsara is, and you say, “It really is unsatisfactory. It really does stink”—that’s good. That’s going to energize you to seek the way to get out. The way to get out is by generating the wisdom that realizes the lack of inherent existence. This is because that wisdom is the total opposite and contradiction of the self-grasping ignorance that holds to things as inherently existent.

All polluted things are in the nature of dukkha. Here, when we talk about this rebirth happening in this way, we can see that what’s at the root of it is the mind. The body is what we get when we’re reborn. But what is it? Where do the afflictions exist? They exist in the mind. What is it that creates the karma? It’s the mind that has the various intentions. The body and the speech don’t act unless there’s a mental intention there. The mind, from the Buddhist perspective, is much more important than the body. Science spends a lot of time and energy researching the body. Likewise, we—because we’re so outer-directed, like we were talking before—we usually want to know about the outside world. But in that way we keep ourselves ignorant. This is because we don’t look at what the real source of happiness and suffering is. It’s the consciousness inside of us and working with that mind. So that’s why the mind is always foremost from a Buddhist perspective.

These first two of the four seals, that all products or composites are impermanent, and that all polluted phenomena are in the nature of dukkha, these two are related. This is because they both describe the first two noble truths. It is especially because things are impermanent that they’re dependent on causes and conditions; and what are part of the causes and conditions? It’s the afflictions and the karma. That’s how those two are related to each other; and then the first two together are related to the first two noble truths—the noble truth of unsatisfactoriness and the noble truth of the origin of unsatisfactoriness.

Now if we just stop there, then everything seems rather helpless and hopeless, doesn’t it? There’s impermanence. There are things that I thought were going to bring me happiness, all these composite phenomena that are supposed to bring me happiness are in the nature of dukkha. What’s the use? I give up. This is, I think, where for many people their depression comes from. It’s a spiritual angst. They have some idea about impermanence and unsatisfactoriness—yet not a clear idea. They don’t know the last two noble truths and there’s only some awareness of the first two. They haven’t heard the teachings. They don’t know that there is the cessation of dukkha and its origin; and that there is a path, a way to actualize that cessation. So the last two noble truths are really critical to the whole, because they present an alternative—and it’s very important to know the alternative. If we see that there’s dukkha and the origin of dukkha; say somebody tells us or we hear something about this. But that’s not all there is to life. There are also true cessations and true paths. Then you go, “Well, how do I get rid of this ignorance that keeps me bound? If ignorance is the root of the whole thing, how do I get rid of it?” And, “Can it be gotten rid of, or is it something that is there and there’s nothing that can be done about it?” Here is where reasoning, intelligence, and investigation are really crucial. This is because we then look at the ignorance, and what ignorance is apprehending which is inherent existence. It apprehends everything as inherently existent, as being independent of all other factors, causes and conditions, parts, and even the mind that conceives of and labels them. This grasping at inherent existence holds things to exist one way and therefore it produces the confusion, the attachment, the anger, and so on.

Then the question is, do things exist the way ignorance apprehends them to exist? Ignorance apprehends things as inherently existent, as truly existent. Do things actually exist that way? Because if they do, then there’s no way to get rid of ignorance because then ignorance would be an accurate perception. But if things do not exist the way that ignorance apprehends them, then it’s possible through cultivating the wisdom that sees how things really exist, to get rid of the ignorance. This is because you disprove the object that the ignorance believes in.

So then we start investigating. Do things inherently exist? That gets us into the third of the four seals, which is, “All phenomena are empty and selfless.” So we start investigating: Do things exist inherently the way ignorance apprehends them to, or not? When we start applying wisdom and we start investigating with analysis: are things independent of other factors? We find that they aren’t.

For example, we were talking earlier in the session about this feeling of me. “I’m just here. I’m me. All these things, I contact but I don’t really change. I’m just me, sitting here, independent of everything and nothing ever really affects me.” So there’s that feeling. Then we start examining it: “Is that true? Is it true that nothing affects me?” We are so easily affected, aren’t we? “Are we produced?” Look at our life, are we produced phenomena? Do we depend on causes and conditions to have this life? Is our life produced or not produced? It’s produced, isn’t it? “Has it always existed?” No. This feeling that, “I’m here and I’m just here independent of everything,” is that an accurate perception? No! Are we going to die? Yes!

This feeling of, “There’s just a me that isn’t subject to change, that exists without depending on causes and conditions.” Is that feeling accurate or inaccurate? Inaccurate! It’s rubbish, isn’t it? It doesn’t matter if we feel it. If it doesn’t stand up to reason, we have to throw it out. We can’t use the thing, “Well, I feel it…” We’ve felt lots of things, haven’t we? It’s like, for example, you are falling in love, and “I feel this person is my soulmate forever.” Then you talk to them however long later and it’s like, “I’m not talking to that person!” Yes, but at the beginning, “Ooooh, I believe we were really meant for each other, divinely meant for each other. We were soulmates from previous lives. We’re going to be together inextricably forever.” We really feel that way and when we feel it, it’s like, “Oh, I’m sure it’s really this way.” We’ve all been that way, haven’t we? Then you wait a little bit of time and it’s like, “Boy! What was I thinking? What was I thinking! What in the world was I believing?”

Just because we feel it’s true that’s not logical evidence. This is why investigation and reflection are so important, and why analysis is so important. When we start investigating, it feels like there’s just this big me here that doesn’t depend on causes and conditions, that doesn’t depend on parts. There’s a self, but it has no relationship to the body and mind. Kind of what you were saying, “Yes, there’s a self—but it doesn’t depend on parts and it doesn’t depend on being labeled.” “Who, me? I exist by being merely labeled?” “Forget it! I exist! I’m not merely labeled.”

But when you look, how does “I” exist? How does the self exist? You have to have the collection of the body and mind. But is the collection of the body and mind the self? No. You also have to have a mind that conceives of those and gives them the label “I” or “person.” It’s dependent also on the mind that conceives and labels. Is there some inherently existent me that doesn’t depend on other phenomena? You can’t find it when you look for it.

Then you see that things are empty and selfless; and that what ignorance grasps onto doesn’t exist. That gives you the confidence that liberation is possible. Then you learn about the true path. The path is not a physical path that you walk on. The path is a consciousness. When we say “practicing the path”—we’re training the consciousness in a certain way. It’s a path consciousness that leads to nirvana, that leads to enlightenment. It’s because things are empty of inherent existence that there’s a path to develop the wisdom that sees things as empty. Therefore the true cessations and the true paths exist. Therefore there are beings who have realized the true path and true cessations. That’s the Sangha Jewel that we take refuge in. The true cessations and true paths are the Dharma Jewel we take refuge in. The one who has perfected the realization of the Dharma Jewel is the Buddha. So then we have the Buddha exists. So we have the Three Jewels of refuge as existent phenomena—all based on the fact that phenomena are empty of inherent existence.

It’s one of these beautiful things Nagarjuna teaches. It just blows you away when you study it. It’s just really incredible.

We’ll get into the third and the fourth seals a little bit more tomorrow. We touched on them this afternoon. Then we’ll get into the Heart Sutra. We’re already dealing with a lot of the material in the Heart Sutra.

Audience: With the second dukkha, where just does Dharma joy fall in that?

VTC: Where does Dharma joy fall when we’re talking about the second kind of dukkha? The Dharma joy when we’re still ordinary beings, it’s still unsatisfactory in the sense that we don’t have the samādhi and the wisdom to really sustain it. But it’s a joy that is going in the direction that we want to go to, that will take us to a kind of joy that doesn’t decline.

Audience: So, as long as we are sentient beings all the pleasurable feelings we experience are…

VTC: Not as long as we are sentient beings because you’re a sentient being until you attain Buddhahood. Before we attain the path of seeing, our joy is tainted by manifest ignorance. Once we reach the path of seeing and become an arya, joy is no longer tainted by manifest ignorance, but it’s still tainted by the latencies of ignorance.

Audience: Prior to that then…

VTC: Prior to that, let me think. There might be some exceptions. For example, when you have an inferential understanding of emptiness, I would say that’s an exception.

Audience: I didn’t follow that when you first started out, you were saying how the first two seals were related because they both describe the first two noble truths. I didn’t understand that. I understand how Bhikkhu Bodhi says that dukkha is such because things aren’t permanent so we’re bummed out.

VTC: So you’re asking how the first two are related? All composite phenomena are impermanent. When we say they’re impermanent, it means they are dependent on other factors, principally their causes and conditions. Then in the second one, we’re saying that those causes and conditions are primarily polluted ones, under the influence of ignorance. This is because the body and mind is produced under the influence of ignorance and karma.

Let’s sit quietly for a minute and then we will dedicate. In your meditation this evening and also in the break times reflect some more on this.

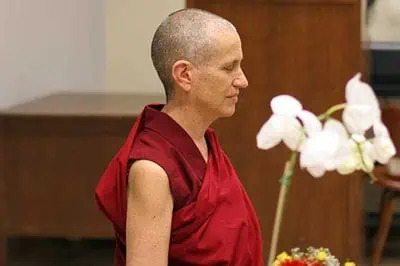

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.