Growing through the Dharma

By L. B.

Tap, tap, tap. “Mr. B. you need to roll up your stuff, someone will be around to give you a sack lunch for your breakfast,” the prison guard said as I eye-balled him through one eye and tried to blink out the gunk of the other. “I take it that I’m going out to court?” I asked. He nodded his head yes and walked on down the tier and out of the disciplinary segregation unit.

I had been waiting to go to court for three months on the charge of taking a prison guard hostage. I had just about given up on them taking me out when they snuck up on me at 4:30 a.m. and brought me out of a good sleep.

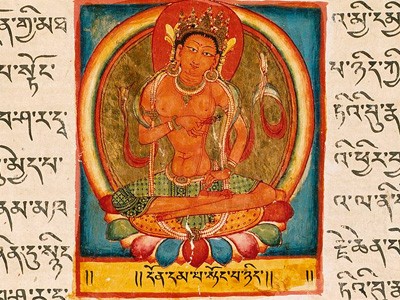

The guard gave me a plastic bag, and I went about putting my meager possessions in it. Before I broke down my altar I said a quick prayer and asked the Buddha to watch out for me. I was a bit apprehensive, yet also excited because it would be a break in the routine and I might even get a visit from my Dharma teacher who lived in the valley down in Salem where I was going to court.

By the time I had finished my sack meal of sandwiches, cookies and a half pint of milk that they gave me, I was ready to go. The guards had me kneel on my bunk while they put the leg irons on me. Then they led me out of the seg. unit and down the long corridors to be processed out and put on the bus. I don’t mind the short steps that leg irons make you take, but I do dislike their abrasively rubbing on my ankles. I knew that by the time the trip was over and I was processed into the state prison, my ankles would be hamburger and would sting for days after. Oh well, this is just another reminder of the karma I have created in my life. Good or bad I have to deal with it.

I was lucky to be one of the last ones on the bus which gave me an aisle seat second row back. If we stopped at one of the other facilities and let some of the incarcerated people off, I might get the front seat next to a window. I sat back and waited for the bus to clear the security gate and hit the freeway.

I knew that the ride was going to be a long one, about seven hours. However, there was some nice scenery along the Columbia River Gorge and also through the passes leading out of Eastern Oregon on Interstate 5. I could deal with the cramped quarters on the bus ride and even the binding leg shackles and wrist restraints as long as I was kept occupied by the passing beauty of the ride into the valley.

For the first hundred miles or so there were some hills and a mountain pass. There wasn’t a lot to look at going through this desert part of the state, but I looked anyway, relishing the dry bushes that were wilted from the summer heat. I tried to see houses and the free people going about their business. I had spent the last three months locked away from any view of the outside world, so even this desert was a treat to look at.

Our first stop was the Two Rivers Correctional Institution. The bus pulled into the security gate and under an awning. I was thankful for this because the temperature was in the low 100’s and while we were there, the air conditioner would be shut off and none of us would be allowed off the bus.

One of the guards gave each of us a sandwich of bread and meat. I should have passed on mine, because we were not allowed any water and those sandwiches were dry. However, I forced mine down. You must eat when you can on transport day because you never know when you will get to eat again on that day.

We dropped off several people and took on some bags of property along with some watermelons and cantaloupes. The melons were for some private use out of someone’s garden and probably for the prison guards’ annual picnic. They sure looked juicy though!

We pulled out after 30 minutes or so and got back on the freeway. I got lucky and managed to get the two front seats to myself. There was plenty of leg room and a really great view! For several hours I watched wind surfers on the Columbia River ride the wind and crash and burn when they came down wrong. I saw a steamwheel pleasure boat riding down the Gorge; it was huge, painted red and white, and looked right out of the old West. I also saw a tug boat pushing several tons of barge up the river and lots of birds swooping or sitting on the water hunting bugs and fish.

A person takes for granted the everyday scenery of life when right in the midst of it. For me, though, it was extraordinary. I watched every car that went by, noted the different makes and models along with the diversity of people.

Before I knew it, we were pulling up to the guard tower at Oregon State Correctional Institute where, 26 years earlier, at the age of 18, I had come to serve my first prison sentence. But instead of being a frightened young boy, this time I was a grown man wondering what my future held.

At OSCI, myself and two others were offloaded into a prison car which drove us to the county jail. I thought that there was some mistake. Surely with my escape record, they would stick me into state prison maximum security and lock me up. But no, they said, “The county jail is where you’re going Mr. Bates.”

It was 2:30 in the afternoon when I stepped out of the transfer car and into the Marion County Jailhouse. I was tired and my shoulders ached from the wrist shackles keeping my arms in one position. I was happy to be un-cuffed and put into the little holding cell before being booked in. As I sat in the side room, I contemplated what might take place, how long I would be there, and how I would be treated.

After 15 minutes, I heard someone ask to watch T.V. When he was told, “No,” he started kicking his door loudly. When the officers went to his door and asked him what the problem was he said that the officers on the previous shift had promised to let him stay out all day to watch T.V. The officer in charge told him that they were booking people in and that he had blown any chance to watch T.V. because he kicked his door. The officer then told him, “Back up and submit to restraints.” He refused to “cuff up” and continued to rant and rave, so the officer sprayed pepper spray into his cell.

A few seconds after it was sprayed, he started gagging, spitting, and yelling that he could not breathe, to which officer replied, “It sounds like you are breathing just fine.”

When this all happened I got on my bunk in the holding cell, sat in the half lotus position, and started chanting the Medicine Buddha mantra in hopes of helping this individual who was clearly in distress. I figured that sending him some good vibes and healing thoughts could not hurt. Unfortunately this man was in his own personal hell realm, and he continued to act out, yell, and put up a resistance. So the guards strapped him in a restraint chair.

The restraint chair is a molded, hard, black, plastic chair that looks like something out of a fighter airplane. The straps that were put over his shoulders locked down his arms and legs so he couldn’t move. Eventually, because he was yelling, they put a cotton hood that is commonly called a “spit mask” over his face. They put him in a room that had a see through Plexiglas wall so they could watch over him, and so he would be out of the way. I saw him as they took me out to be fingerprinted and booked in. My heart went out to him as he sat there in his underwear, strapped to a chair with a cotton hood over his head. It was the year 2005, and we still use torture devices on human beings only now they are called “corrective measures.”

Once they finished booking me in, they led me to the cell that would be my home for the next three weeks. Most county jail and prison cells are alike. They have a metal framed bunk bolted to one wall and a metal toilet and sink usually bolted opposite the bunk. There is also a light and sometimes a slit window big enough to see through yet small enough so that you could not get out. They had put me in the “hole” directly from the prison transport. I had not done anything wrong at this particular jail; however, I am sure my past actions were the reason that I was there now. This segregation cell and the area outside of it had the look and feel of a dungeon. It seemed to be in a time warp where everything was slowed down, and there was an apprehensiveness to the atmosphere. I believe this feeling was due to the past suffering of others in the cell before me. The walls seem to leak out the fear and hopelessness that people first go through when incarcerated.

My first day in that cell was uneventful; I sat around and listened to the five men who were in the cells on the tier with me. My main interest was focused on a slit window that ran the six-foot length down one wall and was four inches wide. Through this window I could see out across the jail property into a few foothills and over to the Oregon State Correctional Institute where I had spent six years in my late teens and early twenties. I had also escaped from this particular prison. So I was loathe to look at it—too many bad memories.

What held my attention throughout my stay at the Marion County Jail was the diverse wildlife that I could see out that little slit window in my cell. There were your typical insects and bugs that hang around in the grass on a hot summer day, but there were also field mice and a couple of industrious gophers digging away happily right out in front of my cell. Watching animals go about their daily lives acting naturally has always interested me. There was even a young crane walking around the perimeter fence in the evening when the sun went down. It would take four or five steps then point its head and long neck straight up to the sky. I think it was sunning itself.

Around 8 p.m. the sprinkler system would come on and I would watch the water shoot out and around in a circle wetting the grass and causing the bugs to jump around. It kept me entertained because I had not seen the outdoors in months.

On my second day in I got up the nerve to talk out my door and ask a few questions. I had been in the jail for roughly 24 hours without any writing supplies and I wanted to know how to go about getting some. I also wanted to know how to go about getting a shower and shave. This was the first facility I had been in where they put you in segregation and did not give you any information on the daily operations of the jail. As it turned out, there was no canteen privilege in this jail while in the “hole,” no out-of-cell exercise, and only three envelopes to send letters out a week. Because I was considered a danger to the safety of the jail, I had to shower handcuffed!

Personally I was okay with it all. Through my Buddhist practice I was learning that having things and enduring suffering or not having things and enduring suffering was okay. I would be happy with or without these things, and it was interesting learning how to wash myself handcuffed!

What did bother me at first was the lack of Dharma materials, such as books or magazines to read and practice with. I had requested some from the library at the jail, but they didn’t have any. I would have to rely on the ceremonies, prayers, and the practices that I had memorized.

For some reason my concentration was not good when I would try to meditate. I could not get comfortable when I sat, I couldn’t keep my focus on what I was meditating on, and my thoughts were like monkeys running around, even though I tried to let go of them. I think the stress of traveling, of being in a different environment, and fear of court and how long I would be stuck in the hole added to my problem. Venerable Chodron told me once that when your practice is dry, (or if you’re having problems) you need to keep on keeping on. So that is what I did. Even though I couldn’t focus, I would try each day.

There were some colorful characters on our tier, and the tier above ours even had a woman in one of the cells. This was the first jail I had been in that had women in the “hole” with men. It was co-ed in that respect and I was astonished.

One of the characters on our tier was Leroy. He is one of those individuals who has seen it all, done it all, and knows the law by heart. He told so many war stories that by the time that I got to see him I had a picture of a guy that was seven feet tall, weighed 300 pounds, and blew fire out of his nose! However, he was only five and a half feet tall, maybe 190 pounds and going bald on top. He had a sense of humor that made you forget all about his bragging and kept you laughing all day.

On my first night in the hole, I was awakened by someone screaming and thrashing about in his bed. I could tell that the person was dreaming because it was one of those soul-wrenching screams that comes from inside of a nightmare. I found out the next day that it was Joe, who lived a couple of cells down from me. He suffered from psycho-seizures. Whenever he went to sleep he would have a seizure and scream and throw his hands and feet around. I felt for him. He had injured himself several times and the jail’s answer to this was to put him in segregation. They said he was faking it, but Joe said he had been having these seizures since he was five years old. Joe was a good talker, though, and I spent several evenings laying on folded up blankets listening to him tell stories. He was finally released from the hole a day before he was due to get out of county jail.

There was one woman that they brought into segregation and put in a cell down the tier from me. Her name was Holly. She had a really interesting, yet sad past. She is an exotic dancer, 24 years old, 5’5, 120 pounds. She came to segregation for an altercation with another woman in the women’s unit. Although she was only 24, you could tell after talking to her for a few hours that she had grown up fast and had an insight into people that was beyond her years. Both of her parents died years ago, and she had been on her own for a long time.

One evening, while the guards were doing a routine cell search they found a plastic comb, a plastic spoon and an extra pencil on Holly. For the next three days they served Miss Holly what is called nutri-loaf. Nutri-loaf is a concoction that is made from blending whatever food was being served at that meal in a blender and then baking it in the shape of a loaf of bread. It doesn’t look very good, and as a rule most prisoners won’t eat it. Neither did Holly. Normally nutri-loaf is given to those who throw their food or abuse their eating tray, not to people who have a plastic spoon. So several of us got together and gave portions of our meals to Holly. Since the quantity of the food that was given to us was very small, we all went a little hungry. I thought this was okay because we got to share each others’ suffering. When we share others’ suffering, we can put ourselves in their shoes and better understand them, thereby being able to show them more compassion.

Miss Holly and I shared many conversations over the weeks that she was in the hole, and we became fast friends. We talked about everything from past loves to past lives and everything in between. It was enjoyable because it had been four years since I had talked with anyone on the level that we shared that did not include a sexual relationship or an expectation of anything more than sharing a moment in life’s passing.

At one point, though, I found that I was starting to become attached to Holly and it was a real eye opener. It made me back up a step and see that suffering would occur if I were to become attached and that I needed to back off. So I did. Once this was done, I was able to let go of the attachment and enjoy Miss Holly once more.

In order to have a place to focus as well as an image of the Buddha during my meditation time, on the wall at one end of my bed I drew a picture that resembled Lord Buddha sitting in meditation. It was drawn in pencil and Lord Buddha had a smile on his face. It brought me comfort to know that I shared the cell with him.

Eventually I was escorted in shackles to my court hearing. I had agreed to plead guilty and not have a long, drawn-out court trial. I viewed a trial as a form of lying because it would involve saying that I was not guilty when I was. Pleading guilty was a chance to keep my vow of telling the truth, and it lessened the burden on the victim by her not having to get on the stand and testify.

Once in the courtroom, I signed the necessary papers and then apologized to the victim and received my time. It brought me peace to be able to apologize; it also shocked the deputies that escorted me from the courtroom. They said that rarely will a person apologize to the victim at sentencing. I was saddened at that revelation from the officer, for it meant that many victims lacked closure in some small way in the ordeals that they went through.

I spent another week in my cell after that day and simply enjoyed the time away from solitary confinement in Eastern Oregon. I would miss the friends I had made here and the camaraderie that we all shared. It seems that in this instance mutual suffering brought us all closer rather than separate and confined by ourselves as solitary confinement is meant to do.

I had learned that growing attached to people brings suffering, and I had some insight into how to let go of the false perceptions I put on people. I may become attached in the future, but at least I was learning to recognize it and stop it. I also learned a bit of what it must have been like for the monks kept prisoner in Tibet, and how it was for them not to have any Dharma materials to practice with. I had to quote from memory what I did know and count on my sincerity to carry me the rest of the way.

I was finally once again shackled hand and foot and put on a bus with other incarcerated people for the seven-hour drive to Eastern Oregon. However, this time a bit of myself was free and soared off into the beauty that encompassed the scenery around us on the drive. Some good had come out of a bad situation and I had to smile. Indeed the Buddha had watched over me and taught me some lessons as well.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.