Buddhist mindfulness and secular mindfulness

This article by Venerable Chodron was published in the September 2021 issue of Eastern Horizon.

Mindfulness is currently a popular practice in our society. It is discussed in news magazines. TV hosts interview instructors of mindfulness. Shops sell special clothes, timers, and bells to help practitioners of mindfulness, and mindfulness sessions are fitted into the work schedule in offices, businesses, and locker rooms. Mindfulness has become the latest craze that is supposed to lead us to relaxation and reduce our stress.

The secular mindfulness practices that are helpful to people across society originated in the Buddhist practice of mindfulness. Today they have developed in a way that diverges from their origin in a spiritual tradition. It is important to differentiate the two types of mindfulness so that people are clear what they are practicing and why.

A Buddhist friend in Singapore who teaches secular mindfulness told me that in a multicultural, multireligious society such as Singapore (and the US), people who are not Buddhist may want to learn secular mindfulness meditation to help them be calmer and to get in touch with their feelings. But they will not be drawn to the practice, and thus will miss out on its benefits, if mindfulness is billed as a Buddhist practice.

On the other hand, people who are seeking a spiritual path and want to learn Buddhism because they seek spiritual liberation or full awakening will want to study with a Buddhist teacher and learn about subtle impermanence, the four noble truths, selflessness, the altruistic intention, rebirth, and so on. They will learn how to do both analytic and placement meditation on these topics, a skill that they will not find in the practice of secular mindfulness.

What is mindfulness?

Buddhism defines mindfulness as a mental factor that focuses on a virtuous object and is able to keep the mind focused on that object. Though the traditional definition calls for a virtuous object as the object of focus, it could also be a neutral one such as the breath. In Pali (sati) and Sanskrit (smrti), mindfulness is the same word as “memory” or “remember.” Mindfulness functions to prevent distraction to other objects. Cultivating mindfulness pertains to both our practice of ethical conduct and to our development of concentration.

Mindfulness in practicing ethical conduct

In the context of ethical conduct, those of us who are Buddhists cultivate mindfulness of our precepts, whether lay or monastic, and of the ten virtuous actions that we aspire to cultivate. We remember the values and principles we want to live by and act according to them. When we forget our precepts, carelessness and complacency ensue. By neglecting to reflect on our values or on what kind of human being we want to be, we get pulled this way and that by objects of attachment and anger that come into the mind. When memory of our values and precepts disappears, we can’t use them to frame or support our day-to-day life and live in an ethical manner.

Mindfulness works closely together with another mental factor called introspective awareness (P. sampajañña, Skt. samprajanya), also translated as “mental alertness” or “vigilance.” This mental factor is like a little spy that observes if we are mindful of our values and precepts and whether we’re acting in accordance with them. It’s a little corner of the mind that investigates, “I’m talking. Is what I’m saying truthful? Does it promote harmony among people? Is it kind? Is this an appropriate time to say this?” Introspective awareness observes, “How is my body moving now? How are my physical movements and gestures affecting other people? Am I aware of the other people in my surroundings and how my actions affect them?”

I read a story in the news that’s a good example of how mindfulness and introspective awareness work together in the practice of ethical conduct. A football player who was 6’5” and weighed 300 pounds was working out in a park. He heard a woman screaming and went to investigate. She was being attacked by a man in broad daylight. As the football player ran over to help, he realized that he was a very big person and that people could get scared by him, especially if he’s coming at them quickly. He ran with that awareness because he didn’t want to freak everybody out, and he dragged the man away from the woman and sat him down. Another man came along who kept the man there until the cops arrived. The football player then led the woman some distance away and helped her calm down because she was quite distressed. All this time, he was mindful of his size and the effect that it had on others.

We say he was mindful, which is true, but he also had introspective awareness. He was mindful of not wanting to scare anybody and he had the introspective awareness to be aware of how he was moving, so that on his way to help nobody got frightened except the attacker. That’s a good example of mindfulness of how he wanted to behave and introspective awareness checking that he was acting that way. The police department declared the football player and the other man heroes, but the football player said, “I’m not a hero. I was just doing what any person should do when somebody needs help.”

Mindfulness in developing concentration

In the context of developing the single-pointed mind of serenity (shamatha), mindfulness focuses on the object you are using to cultivate concentration. This should be an object that you are familiar with. If you’re using the Buddha as your meditation object, you look at a statue, painting, or an image of the Buddha to remember how he looks, the expression on his face, his hand gestures, and so on. Then you lower your eyes and bring that image to mind in your mental consciousness. Serenity is cultivated by the mental consciousness and the object of serenity is a mental object. Serenity is not attained by a visual consciousness staring at a candle or a flower. Mindfulness remembers the object of concentration and functions to keep the attention on it, so you’re not remembering the movie you saw yesterday or what somebody did last week that bugged you. You’re not drowsy or falling asleep, but are focused on the object of meditation.

In meditation, introspective awareness checks up to see if your mindfulness is still on the meditation object, if the mind is restless and distracted to an object of attachment, or if the mind is dull, lethargic, or lax. One corner of the mind from time to time observes, “Am I still on the image of the Buddha?” If you’re not, then it activates the appropriate antidote that enables you to renew mindfulness on the object of meditation.

This is how these two, mindfulness and introspective awareness, function in tandem in most situations. They are two mental factors we should put effort into developing, not only in our meditation practice, but also in our daily life.

Benefits of developing mindfulness and introspective awareness

In the Buddhist path, we follow the three higher trainings of ethical conduct, concentration, and wisdom. The order of these three begins with the easiest and progressively becomes more difficult. By practicing ethical conduct, our mindfulness and introspective awareness automatically improve. We practice mindfulness of our precepts regarding verbal and physical activities and cultivate introspective awareness that guides us to live according to them. Our relationship with others improves and we have less guilt and regret—two factors that impede the cultivation of concentration. Since our mindfulness and introspective awareness are already somewhat developed, cultivating serenity on the object of meditation is easier.

In our daily life, in addition to cultivating mindfulness and introspective awareness on what we’re saying and doing, we also monitor the mind because our physical and verbal actions originate in the mind. We make sure our minds are directed toward virtuous objects. It’s helpful during the day to check, “Is my mind in La-La Land imagining something beautiful that I want? Or am I in Regret Land thinking of something in the past that I did that I don’t feel good about? Or am I strolling down Memory Lane thinking of all these people I knew in high school and wondering what they are doing now?” When introspective awareness notices those kinds of thoughts, stop and ask yourself, “Is this a good object to focus on right now? Does thinking about this have any benefit for myself or others?” We’ll notice that many times what we’re thinking about is a total waste of time.

Buddhist mindfulness and secular mindfulness

Mindfulness is now the latest and biggest fad, like yoga was years ago, and it’s important to distinguish secular mindfulness and Buddhist mindfulness: they are not the same. Secular mindfulness grew out of the vipassana meditation taught in Theravada Buddhism. In the ‘60s and ‘70s young people such as Jack Kornfield, Sharon Salzburg, Joseph Goldstein and others went to Burma and Thailand where they learned vipassana (insight) meditation, which included the practice of mindfulness, and the Buddhadharma. But when they returned to the US, they taught mindfulness and vipassana simply as a meditation technique that would help people be calmer and more aware. Not wanting to teach a religion, they did not teach mindfulness and vipassana in the context of Buddhist teachings such as the four noble truths, the eightfold noble path, or the three higher trainings. As far as I understand, the secular mindfulness movement came out of that. While secular mindfulness has its roots in Buddhism, it differs from the mindfulness that is practiced in Buddhism.

For example, Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn started a program called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). Years ago, when I first met Dr. Kabat-Zinn, MBSR was something new, and it was exciting to see the results. Now there’s a training program and people can be certified as teachers and offer courses and retreats. For people who have chronic pain, MBSR works very well. It is a secular training open to people from all religions or no religion; it is not the practice of Buddhist mindfulness, which involves practicing a specific form of ethical conduct, learning about rebirth, and understanding what to practice and abandon on the path to liberation and full awakening.

Secular mindfulness and Buddhist mindfulness differ in several regards: the motivation, context, technique, result, and overall approach. How one applies mindfulness is different as well. Some of the differences are in the following areas.

1.Motivation

In Buddhist practice, our motivation is either to obtain liberation from samsara (i.e., to attain nirvana) or to attain full Buddhahood. Our motivation is to purify our mind completely and overcome all the mental afflictions and ignorance. Those who aim for arhatship strive to become a liberated being who is no longer trapped in samsara. Those who aim to become Buddhas will develop bodhicitta—the aspiration to become fully awakened in order to best benefit all living beings and guide them to full awakening. They will exert effort to overcome all traces of the self-centered attitude and replace it with a sincerely altruistic intention to be of benefit to sentient beings. In other words, the practice of Buddhist mindfulness is done with a compassionate motivation, and this motivation permeates all aspects of our lives as Buddhist practitioners.

The motivation for doing secular mindfulness is basically to be calmer, feel better, and have fewer problems in life. The motivation is entirely about this life—to calm stress in this life, to become more peaceful with less psychological turmoil in this life. There is no talk of future lives, liberation, or full awakening.

2. Context

In Buddhism, mindfulness practice is explained in the context of the four noble truths: we are beings who have duhkha, or unsatisfactory experiences; these experiences come from circling in samsara due to ignorance; there exists a path to practice to purify the mind and overcome these causes; and this path leads to nirvana, a state of final peace and fulfillment. Buddhist mindfulness is combined with wisdom that investigates and penetrates the ultimate nature of persons and phenomena. It is practiced in addition to other meditations and methods that together develop different aspects of our mind. It is supported by ethical conduct and compassion, qualities that manifest in our daily lives.

Secular mindfulness is practiced in the context of becoming a more productive employee or a better parent and partner. There is no talk of ethical conduct or compassion; there is no guidance on how to discern a virtuous mental state or a nonvirtuous one. That could lead to someone thinking, “I’m mindful of anger arising toward this person who insulted me; I’m mindful of wanting to retaliate; I’m mindful of opening my mouth and insulting the other person; I’m mindful of feeling satisfied because I put that person in their place so they won’t insult me again.” Certainly such “mindfulness” of our anger and craving and the actions we do motivated by them won’t lead to happiness.

3. Technique

The meditation technique is also different. In Buddhist mindfulness practice, we meditate on the four establishments of mindfulness: mindfulness of the body, the feelings, the mind, and phenomena. Here mindfulness is not bare attention that observes whatever arises in the mind without judgment as in secular mindfulness. Rather, the Buddhist practice of the four establishments of mindfulness involves developing a penetrative, probing mind that seeks to understand exactly what this body is, what pleasant and unpleasant feelings are, and how craving pleasant feelings and aversion to unpleasant ones operate in our lives. We are mindful of how happy feelings produce attachment, unhappy feelings produce anger, and neutral feelings produce ignorance or confusion. The four establishments of mindfulness is a penetrative study of the body and mind and the person who is designated in dependence on the body and mind. Its ultimate purpose is to generate the wisdom that overcomes ignorance and craving.

Buddhist mindfulness isn’t just watching one’s mind. It involves studying the relationship between body, mind, external influences, and karmic tendencies implanted on the mindstream during previous lives. It makes us aware of internal and external conditions that influence our lives, which enables us to see these conditions with wisdom and question our assumptions and preconceptions. Buddhist mindfulness leads us to examine whether the way things appear is actually how they exist.

Furthermore, in Buddhist practice, mindfulness just is one part of our spiritual practice. There are many other practices we do because our mind is complex: one practice alone is not going to bring liberation. Our meditation practice is based on studying and reflecting on the teachings of the Buddha.

None of this is present in secular mindfulness. Although the various instructors of secular mindfulness have slightly different techniques, most of them center on observing the breath, experiencing any sensations and feelings that arise, and observing any thoughts that arise without judgement.

Nowadays, secular mindfulness is inclining toward entertainment. When a journalist from a wellness magazine asked me to write about mindfulness as practiced by Buddhists, she told me about the techniques of several of the leading instructors of secular mindfulness. These included listening to soothing music while watching the breath, looking at beautiful landscapes on your computer screen, and watching pretty shapes and calming images displayed on the screen. This is directed at lessening stress and relaxing the mind, which certainly helps people, but is not in itself spiritual practice.

Can learning secular mindfulness lead to an interest in Buddhism? For some people, perhaps it will. However, my experience is that the great majority of people who come to Buddhist teachings were not led there by practicing secular mindfulness.

4. Result

Secular mindfulness does help people. It’s taught in banks, to sports teams, to real estate agents, and other areas of endeavor to help people relax and alleviate stress. It makes people more productive and better at their jobs. However, it doesn’t spur them to examine their motivation, live ethically, or be compassionate toward others. In some cases, secular mindfulness may make people better cogs in the wheel of capitalism. But this is not Buddhist mindfulness, nor is it spiritual practice.

In short, both types of mindfulness have value. Secular mindfulness helps mitigate daily stresses and calm the body and mind. Buddhist mindfulness transforms the mind so as to eliminate attachment, anger, and confusion and develop impartial love, compassion, and wisdom. Buddhist mindfulness, when conjoined with other practice, leads to liberation and full awakening.

5. Overall approach

Another difference between the two types of mindfulness that is worth highlighting is that Buddhist mindfulness and Buddhist teachings in general are offered free of charge. Some Buddhist centers in the West charge, but in most Buddhist organizations, especially in Asia, teachings and meditation instruction are freely offered. This creates an economy of generosity where people want to give back because they’ve received benefit from the Dharma teachings and teachers. They know the monastics need to eat and the temple must pay for electricity and other expenses. Participants give from their heart and according to their ability, there are no charges, and nobody is excluded or prevented from receiving Buddhist teachings because they don’t have money.

Practitioners of secular mindfulness often buy an app. Prices vary and discounts are advertised. That adds a very different dimension to secular mindfulness: it is a money-making endeavor and a business activity. Practitioners become customers paying for a service and in that way they have leverage over what is taught. The money clients pay is a motivating factor for the instructors, who may alter their meditation technique or add a particular slant in order to interest more people.

Buddhist teachers, on the other hand, are part of a lineage that goes back over 2,500 years to the Buddha. Although certain external factors may be altered depending on climate, culture, or other external circumstances, the teachings themselves are not changed.

Both Buddhist mindfulness and secular mindfulness benefit their respective audiences. Knowing their similarities and differences enables us to seek the type of practice that will meet our present needs

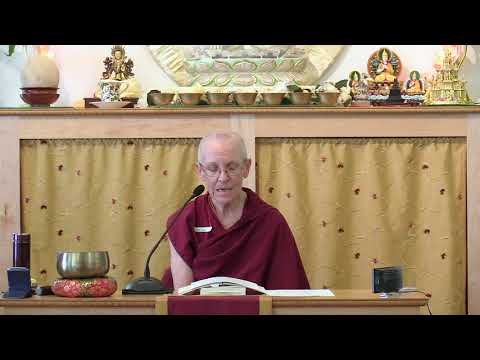

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.