Introduction to the taking and giving meditation

A talk given for a Buddhist meditation class at Smith College, USA.

- Obstacles to taking on the suffering of others

- Self-centeredness, self-criticism, and rumination

- Seeing that our parents and others love us

- Why the self-centered thought is unrealistic and makes us miserable

- The benefits of caring for others

- Questions and answers

- If we don’t care for ourselves and take care of our basic needs first, how will we have resources to care for others?

- Doesn’t anticipating future events allow you to plan accordingly and save you from future harm?

- How do we discern when it’s appropriate to correct someone’s incorrect information, and when it’s better not to engage?

- What’s the different between metta and tonglen, and why does tonglen seem to involve more advance preparation?

I’ve been asked to talk about a meditation in our tradition called the taking and giving practice, or Tonglen in Tibetan. The idea is that you imagine taking on others’ suffering and giving them your happiness. But in order to even imagine this, we have to understand why to do it and how to get beyond the obstacles that our mind puts up. That’s what I’m going to talk about. We’ll start with the obstacles.

When you think of giving others your happiness and taking on their misery, what is the biggest block to doing that in your mind? We’re not talking physically, just in your mind. Our usual perspective is that if there’s something good to be had, I’ll take it, and if there’s a problem, you take it. That’s how we usually practice taking and giving: I’ll take the good stuff and you take the bad stuff. This is a view that’s very prominent in our culture, that we’ve been raised with, and it’s a view that we also have instinctively. There’s this idea that there’s a real “me,” and there’s attachment to “me,” and we think, “I’m the most important person around here, so my happiness and my suffering are more important than anybody else’s.”

Think about it. We always put ourselves first, and we’re told to put ourselves first—because if you don’t care about yourself nobody else will. And we usually think caring about ourselves means taking all the good stuff for ourselves, so we want possessions, we want reputation—we want to be liked and accepted and have other people talk very nicely about us. Behind our back they aren’t supposed to criticize or mention our mistakes. We’re very attached to what other people think about us.

Are they approving, are they disapproving? Am I meeting society’s standards or am I not? Am I worthwhile or am I a failure? All these kinds of thoughts are buzzing around in our minds all day, and who is the center of all these kinds of thoughts? It’s ME, isn’t it? You don’t worry about whether or not everybody likes your friend. You don’t worry about whether or not your friend’s hair looks good. You worry about your own hair.

You think about your own family. “Am I doing what Mom and Dad want? Are they going to be mad at me? Are they going to cut me off so that I have to get a job to get through school?” We always think about our own stuff, but other people have exactly the same things going on in their lives. Their problem is kind of like, “Okay, if it’s a friend, it’s a problem, but it’s not a big deal.” But what happens to ME—that’s a really big deal. It’s more important than what happens to anybody else.

So, we’re friends; I think we can admit to each other that we think like this. It’s kind of obvious. People know that about us anyways, so who are we trying to pretend for? Who doesn’t know that we think about ourselves first? But the thing is that we have to look at that kind of self-centeredness and question whether or not it really helps us in any way. Does it help anybody in any way when we’re just ruminating about what’s happening to me? When we ruminate, one little thing happens and our mind creates a huge story about it.

In the morning, you walk into the dining room or the classroom, and people don’t all say, “Hello” to you. And somebody who you thought was your friend doesn’t say “Good morning” to you; they just go on and do what they need to do. So then all of the sudden we go, “Oh, my friend didn’t say good morning. Are they mad at me? Did I do something they don’t like? Maybe something’s wrong. Maybe somebody else told them something bad about me, and that’s why they aren’t saying good morning. We can go on and think about that for a really long time. We can develop all of these theories: “Oh, they not only didn’t say ‘Good morning,’ but I saw that slight smirk on their face. I’m in trouble. What’s going on?” And we do this again and again.

And you go back to wherever you’re living thinking about it again and again, and then it changes to how other people also didn’t say “Good morning” and maybe my whole group of friends is mad at me and maybe I don’t fit in. It’s terrible. We get all huffed and puffed about these kinds of things. Do we know why our friend didn’t say “Good morning?” We have no idea why not. Maybe they had a stomach ache. Maybe they just got a phone call and were thinking about what somebody else told them. Maybe they just remembered they have to turn in an assignment they forgot about, so they are preoccupied. But we don’t think about that. We make everything self-referential: “Do they like me? Do they not like me? Do they accept me? Do they not accept me?”

And then when it comes to how you look: “Do I have the right colored hair, and is it going the right way? Do I have the figure that looks like all the women in the magazines?” Actually, nobody looks like the models in the magazines because all those photos are airbrushed. But we all go, “I should look like that, but I’m too big here or too small there. Nobody is going to like me. I don’t look like them; I don’t dress like them.” We spend a lot of time ruminating about all this kind of stuff. Does it make you happy? No.

It makes us completely miserable. Because we’re very self-critical—unreasonably self-critical. We would never criticize anybody else that bad, but we look at ourselves and we go, “I’m just a loser. I can’t get it together. I can’t do anything right. I’m just not going to be able to make it. School’s too difficult; the relationship with my parents is too hard. I won’t get into graduate school and then I won’t get a good career and I won’t make a lot of money. I’m going to wind up on the streets with a shopping cart, and my life is going to be a complete disaster.” Is that really true? [laughter] It’s not true, but we go around and around and around thinking about it.

We are not the center of the universe

Do we think about the lives of the people who are already living on the streets right now? Do you think about their lives? Do you think about the people who didn’t have enough money to pay the electric bill or the rent, so they had to move out of where they were living? Do you think about people who have various illnesses and can’t stay with their families? Do we think about them and their lives, sitting on the street and not having any money? Meanwhile, for us, we think, “I don’t have any money,” but we have credit cards and money in the bank. We make such a big deal about ourselves in a way that is totally unrealistic.

It’s like, believe it or not, we are not the center of the universe. There are other people here who have feelings, and the more I just go around and around about myself and all my poor quality views of myself, the more unhappy I am. It doesn’t do any kind of good at all. It doesn’t benefit anybody else. It doesn’t benefit me. Plus, most of it is false.

When you’re sitting there going, “I don’t look right. Nobody is going to like me,” is that true? Is it true that if you don’t look the way you’re “supposed” to look as a Smith student, that nobody is going to like you? It’s not true, is it? When you didn’t do as well on an exam as you had wanted, you think, “Oh, I can’t do anything right?” Is that true? You can’t do anything right, really? You can make a cup of tea. I bet most of you can drive. You can read and write. You can do a lot of stuff. You can’t say, “I can’t do anything right.” That’s totally false.

What I’m getting at is that we lie to ourselves about ourselves. All this self-critical kind of stuff, if we really examined it, we’d find it is not true. We get depressed and we say, “Nobody loves me,” but is that really true? Is it that nobody loves you or that a lot of people love you but how they show their love is different than the way you would like them to show it? They actually are quite fond of you and love you a lot. They may not understand you real well, but they care about you.

I work with people who are incarcerated in prisons—talk about people who have problems! Some of their parents don’t communicate with them when they are in those places, but what’s amazing is that that doesn’t happen so much. To their mother, even though he is locked up with a long sentence, that child is still the most beautiful child in the world.

I know all the time when I was growing up, especially during my university years, I thought my parents didn’t really love me. But they did love me, it was just that the way they showed the love was different than how I wanted them to show the love. My parents grew up in a totally different generation with different things going on in society, so the things they thought were important were different than the things I thought were important. That’s not only because I’m a different person, but because the country we are living in is totally different than it was when my parents were growing up. So, for me one thing was important and for them other things were important. But they still loved me.

It’s important to see that how we relate to ourselves with all this self-criticism really locks us inside of ourselves. We become very tight and very depressed inside, and none of it is true. You might say, “She’s just saying that. She doesn’t really know. I’m actually just these horrible things.” No. From the Buddhist viewpoint, we all have buddha nature. We all have the potential to do a lot of different things. We have the seeds, the potential, to do many things, and we have to water those seeds. We have to nourish those seeds instead of hammering at ourselves and telling ourselves we’re not worthwhile.

Here’s another example to show how we put undue emphasis on ourselves. Venerable Damcho is the person who interfaced and worked to make this talk happen. Let’s say somebody walked into the room and looked at Venerable Damcho and said, “We were working on this project together, and I trusted you to do this and that, and what kind of friend are you to act that way?” Then Venerable Damcho would be very upset, and she’s my friend, so I would say, “That person is just venting. What they said: examine it. If you did slip up, own it. If you didn’t slip up, just know they are venting. Don’t get upset about it. Chill out.” But if the same person walked into the room and said, “Chodron, we were working together, and I trusted you to do this part of the project, and you completely flaked out and let me down,” that would be a national catastrophe. The war in Ukraine: doesn’t matter. School shooters, little kids dying: doesn’t matter. Somebody criticizing me is the most important thing in the universe today! And I would get really bent out of shape.

Is that really a realistic way to react when somebody says that kind of thing to you? It’s not. We’re just blowing it up and making it into the biggest disaster in the whole world. And it’s not. If somebody criticizes me then I look at what they said, and if it’s true, I own it. I don’t justify it and rationalize it or deny it. I just say, “You’re right. I need to get on top of this.” If what they said is not correct then they may not have the right information. So, you give them the correct information, and then you give them some time to chill out. But there’s no reason to get so upset about it.

If somebody tells you that you have a big nose, are you going to go around covering your nose and saying, “No, I don’t have a big nose. What you’re saying about me is false.” Do you go around covering your nose all day? I have a big nose. Everybody knows that. Everybody sees that. If somebody points out a fault that I have, it’s like saying I have a big nose. Everybody can see it. What are we going to do, deny it and cry? No. If people don’t like me because of my big nose, that is definitely their problem. And I’m not sure I want friends who judge people based on the size of my nose anyway. Are those the kind of friends that I want to have? No, not really.

If somebody says something about me, criticizes me, and what they say is false, then it’s like somebody saying, “You have horns on your head.” Then we just say, “No, I checked. There are no horns, so what you are accusing me of didn’t happen or the explanation is something else.” Again, there’s no reason to get angry or upset. What they said isn’t true, so why get angry and upset? Either way, whether somebody criticizes us and it’s true or it’s not true, there is no reason to get upset.

Turning our attention to others

We need to learn how to evaluate ourselves in a more accurate way and to realize that we are one among many. In terms of human beings, there are now like 8 billion human beings on this planet. We believe in democracy, right? If we take a vote, who is more important, me or the other seven billion nine hundred ninety-nine million nine hundred ninety-nine thousand nine hundred ninety-nine people? Who is more important? Is it me or everybody else? So, why not care about everybody? I’m really not the most important person.

That’s why it’s important to turn my attention and care about other people, not because I have to or because I’m a people pleaser and I want them to like me, but out of a genuine awareness that there’s another person just like me that wants to be happy and doesn’t want to suffer. There are all these other people, and they feel exactly like me: they don’t want the smallest bit of pain, and they want happiness. So, what’s so special about me that I think I’m the only one who deserves happiness and to be free from suffering? That’s a bit unrealistic.

Also, and this is a very important point, as long as I live really thinking about me all the time, the more unhappy I’m going to be. Here’s something His Holiness the Dalai Lama said: “If you want to be happy, take care of others, care about others.” We might think, “Wait a minute, that’s the opposite of what we think in America. In America, it’s me first!” But the Dalai Lama says it’s not me first. In fact, the more you live with a me first attitude the more you’re going to be unhappy. Why? Because every small thing that happens to you becomes a big deal.

When we’re that self-centered, we can’t really evaluate well what is accurate and what isn’t because everything becomes self-referential. When we do that, we exaggerate it, and we’re looking so closely at what people think about me: “Am I doing everything right? Am I going to fit in?” The more we think like that, the more we’re unhappy. You’re miserable thinking about yourself, and none of it is true.

And then the way we relate to other people is that we don’t care about them. We’re just trying to get everything good for ourselves. So, what happens when we don’t care about the people around us? Then we live in the middle of a lot of unhappy people. If we don’t care about the people around us, and they are miserable, they let us know they are miserable. What do you think the demonstrations after George Floyd’s murder were saying? There were a lot of people saying, “I’m unhappy. Do you care about the fact that I’m unhappy? I feel danger when I see a police officer. Do you care?” Saying “I don’t care. Why are you so angry?” doesn’t make them happy, and then you continue to have demonstrations. If you say, “Yes, we care. What can we do to help your situation?” then there’s a way to resolve the problem.

Let me give you another example. This relates a lot to public policy. I lived in Seattle some years ago, and there was a time when there was a school bond on the ballot to vote whether to increase property taxes in order to finance the public schools. There was a big debate in the city about it, and some people were saying, “I’m older. My kids are grown up. I worked hard and have a beautiful house—it’s on five acres of land and a lovely, gorgeous big house—so why should my property taxes increase to pay for somebody else’s kids to go to school? That’s not fair. People should pay for their own kids to go to school. I shouldn’t pay for them.” But if the school doesn’t have enough money, and there are no after school activities for children, what do kids do, especially in lower middle-class or middle-class neighborhoods? The parents are both working, so the kids live in the streets. And then what happens? They get into all sorts of things, and if they happen to get into drugs, well, drugs are an expensive habit.

Whose house are you going to break into if you need money to pay for your drugs? Well, wealthy people—they are the ones who have money. And they are the ones who didn’t want to pay taxes so that the kids of poorer people could have after school activities. So, there’s a group of people who said, “I don’t want to pay for them. They should pay for themselves,” but in doing so, they are creating a society where those kids who now don’t have after school activities are getting into trouble, and they are now stealing from the ones who didn’t want to pay more taxes to fund the after school activities.

For me, that’s such a big example of what His Holiness said: if you care about your own happiness, take care of other people because otherwise you live around a lot of unhappy people. You can see this in your family; you can see this with your colleagues; you can see this in all of society. When we don’t care about others, it creates this horrible ambiance. And that’s what’s happening in our country right now. It’s happened before; this isn’t the first time. But everybody now has the identity of being a victim. Everybody is persecuted now. Everybody is oppressed. This is what a lot of politicians are telling us, about even the people in power—the poor former President, look how many people are treating him unfairly. He has how many billions of dollars, but he’s a martyr because people are chasing after him. It’s a witch hunt. That’s the way of making you feel like that because you just care about yourself, and you’re not looking at how you’re living in a world with not only 8 billion other humans but also fish and insects. There are so many other beings here.

Why do I as one person think that I’m the most important one? And that thought that thinks I’m the most important one is actually the thought that makes us miserable. Here’s another example of this. I had a very good friend who got pregnant, and she was going to go to some other state to visit her sister before she had the baby. My friend told me, “When I get off that plane, my sister is going to say hello and then say I’ve put on some weight. My sister is always talking to me about my weight and my looks, and I know that’s going to be the first thing she says when I get off the plane.” She hasn’t gotten on the plane yet. Her sister doesn’t even know she’s coming yet, but she has the whole scene all planned out, and she’s already unhappy about how her sister is going to greet her.

Nothing has happened, and she’s already miserable. She’s already worried about her sister’s perception of her weight, but since she’s pregnant she should put on some weight. If her sister said she put on some weight, it wouldn’t even be a bad thing. But do you see how nothing has happened but she’s unhappy about it already? This is a result of this self-centered thought. It’s an example of how it makes us unhappy.

Whereas, when we say, “Okay, I didn’t get what I wanted or I didn’t do as well as I wanted to do, that’s okay. Let’s open my eyes and care about the people around me.” When you have this affection and care about other people then you’re much more peaceful in your own heart, and you create a peaceful ambiance around you so that people can live together more harmoniously.

Questions & Answers

Audience: If we don’t care for ourselves and take care of our basic needs first, how will we have resources to care for others?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): You know the answer to that question. I’m talking about the feeling you have inside, not what you do. Clearly, you need shelter and clothes and food, and you can go out and do what you need to in order to get those things. But you don’t have to do it with this feeling of “I want this now, and there may be a lot of people who need food, but I’m going to feed my face until I’m stuffed, and I’m not going to share it with anybody else.” You live in a practical way. You have to take care of yourself, but what I’m talking about goes above and beyond just taking care of ourselves, just doing what we need to survive. You’re asking, “If you don’t have all these things you need then how can you be happy and care for others,” so let me tell you another story related to that.

This was a story told by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Tibet was overrun by the communist Chinese in the late forties, early fifties, and in 1959 there was an uprising against the occupation and the Dalai lama and many Tibetans fled and became refugees in India and Nepal. After that big flood of people came out, China closed the borders, and they started arresting people. Those who were monks and nuns were thrown in prison because they didn’t have the right politics. And actually, they weren’t even political; they were just trying to live their monastic life, and they got thrown in prison. After some years, some of them were able to escape and get to India. When those people made it to India, the first thing they wanted to do was see the Dalai Lama. In their society, he’s number one, and if you have a chance to attend his teachings do it because he’s an exceptional person.

He was telling a story about one of these monks who fled and was able to escape after being incarcerated for many years. His Holiness the Dalai Lama asked him, “What were you most afraid of during all those years you were incarcerated?” The monk had been beaten; they had used electric prods to torture them—the situation was horrible. So, he asked what he was most terrified of. The monk replied, “I was most afraid of losing my compassion for the prison guards.”

Think about that. This is somebody who has been tortured and incarcerated, and the thing they cared about most, or the thing they feared the most, was losing their compassion for the people who were torturing and imprisoning them. This monk had food, shelter and whatever, but it was pretty awful there. But his concern was to have a kind, tolerant, understanding attitude for the prison guards. If you have that kind of attitude, and you are incarcerated, you are going to have a better relationship with the prison guards than if you have an angry attitude. I think this monk realized that most of the guards were probably soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and most of them probably came from impoverished villages and did what they did to send money back to their parents and family who were very poor. It wasn’t like they were inherently evil. They went into that situation, and some of them were probably conscripted, and then they were conditioned by the people who trained them to be soldiers and prison guards. That doesn’t mean they are evil people.

It’s similar for the guys in American prisons that I work with. Most people who are incarcerated hate the prison guards because they don’t treat them very well. But why don’t they treat them well? It’s because the prisoners don’t treat them very well. There is one person I know who is kind to the prison guards. He greets them and shakes their hands and treats them well, and as a result, the prison guards treat him well. Whereas before he encountered Buddhism and started working with his mind, he was rude and crass with the guards. And if you disrespect the guards, what are they going to do? They will act the same way toward the inmates. How we treat others is very much how they treat us back. So, we treat people kindly not just so they will like us—because that’s coming back to me again—but we treat them kindly because they are human beings just like us who want to be happy and don’t want to suffer.

Audience: Doesn’t anticipating future events allow you to plan accordingly and save you from future harm?

VTC: If I know I’m going to meet a person today that I’ve had a difficult relationship with in the past then I think, “Okay, when I meet them, I’m going to be pleasant to them. And if they say something a little bit rude to me, I’m not going to make a big deal out of it.” That way I can anticipate it. I’m not saying it’s going to happen, but if it does happen, I’m prepared. Then I practice being tolerant in my own mind, reacting to what they might say in a way that I don’t make such a big deal out of it. I realize, “Okay, something is happening with that person. That’s okay. My response is to be kind and to be understanding.” This doesn’t mean that I do everything everybody wants, and it doesn’t mean I let everybody take advantage of me. It just means that I try not to be quick and judge them and react with anger. That kind of anticipation may be helpful.

If you’re going to talk to your parents about something you know they probably won’t like, you think about it beforehand: “How can I say this in a way that they will understand? How can I say this in a way that isn’t going to push their buttons?” That kind of thinking in advance is very helpful. What my friend was doing wasn’t that. It was Creative Writing 101 of a horror story starring me. And that’s totally useless. If she had thought to herself, “My sister may comment on my weight: so what? I’m pregnant. Of course I’m gaining weight.” Then of course her sister may or may not say that, but she’s already prepared her mind, and that’s very helpful.

Audience: How do we discern when it’s appropriate to correct someone’s incorrect information, and when it’s better not to engage?

VTC: It depends on the situation a lot. You’re thinking of a specific situation, so what I say may or may not apply to it because I don’t know your specific situation. Just keep that in mind. It depends on what the situation is. Say somebody is coming to me and trying to convert me and wanting me to go to their church, and they’re saying, “You’ve got it all wrong. Jesus is the savior, and you’re going to hell unless you believe in Jesus. Come to church. I want to help you. I have compassion for you and want to help you. So, come to church with me.” If somebody says that to me, I feel like they have incorrect information. I don’t think I’m going to hell because I don’t accept Jesus. And this situation has happened to me many times, usually on long flights when I’m sitting next to somebody. [laughter]

So, in that kind of situation, if I think that somebody is holding tightly to their own views—as I find some people do about religion—then I’m not going to correct their information because they are not open to hearing other ideas. What I will say—and this is what I do when people come to the door also—is, “I’m a Buddhist, and I live by the same values you do: not killing, not stealing, speaking truthfully and honestly, forgiving people. I try and live by those same values, and I think those values are good for all of us. You follow those values in your religion, that’s wonderful. Please continue to live a virtuous life. I will do the same. Thank you very much.” And then I end the conversation.

On the other hand, it’s different if I meet people who are willing to dialogue. We have a few Catholic sisters who live nearby, and we’re good friends, so we dialogue about all kinds of things. We’re not trying to convert them, and they are not trying to convert us. They told us that before we moved in, they had been praying that other spiritual people would move to the neighborhood. Then we moved here, and they were very happy.

If it’s a personal situation that somebody really dumped on me, I’ll assess whether that person is at a place right now where they can actually hear another idea. There’s something called a “refractory period,” which means that when you have a strong emotion, at the time of having that emotion you can’t see anything that doesn’t fit in with what you are feeling. So, if I’m talking to somebody who is totally irate, really angry, saying something to me about my behavior or whatever else, then even if they don’t have the correct information, I’m not going to try to give them the correct information because they aren’t in a place where they can hear it. I’m instead going to listen to them and repeat back in my own words what I hear them saying. “Oh, you seem really upset because you believe that I did this,” or “You feel really left out because I did X, Y, Z.” Try to pay attention to what they are thinking, what they are feeling, what their needs are. And then that helps them to calm down. Then, when a person has calmed down—and it may take some time—so after a few more days or a week or whatever, go to them and say, “There’s a little bit of a back story that I think might help to ease the upset you had about this situation.” Talk to them at that time.

When people get into arguments, that’s what’s happening. Both of them are in the middle of a strong negative emotion, and they can’t hear each other. I notice this a lot, especially here at the Abbey. If you’re ever the director of something, one of your rewards is that everybody blames you for whatever goes wrong. That’s what you get for being in a position of responsibility. [laughter] I’ve had people get really mad, maybe at somebody else, not me, but they are really in the middle of a strong emotion and asking for help. So, I will try and give some advice, and then I’ll ask afterwards, “Can you repeat back to me what I’ve just said?” And they can’t. Because they had such strong emotion at that point that they couldn’t hear anything.

I have a friend who thought she was suffering from migraine headaches. She went to a doctor, and the doctor said, “From the symptoms you’re telling me, I think they are stress headaches, not migraines.” She totally shut down. She said, “For years people have been telling me I have migraines. This is not stress. I have migraines!” She was so upset with the doctor for saying this that when I talked to her later, she couldn’t remember anything he said about things she could do to alleviate the headaches. She had been so stuck in her emotions at that point. At that point she was still really upset, so I tried to talk to her about her feelings. And then after that, she said, “You know, I tuned him out.” It was very interesting. It’s a good example of how people can’t take in new information when they are in the middle of a strong emotion.

Audience: What’s the difference between metta and Tonglen, and why does Tonglen seem to involve more advance preparation?

VTC: Metta is one of those preconditions for doing Tonglen. It’s like learning your arithmetic. Tonglen is like going on to Algebra or Calculus. Metta is a way to prepare your mind for doing the taking and giving meditation. Metta is actually really difficult when you dig deep inside. Has the class had a metta meditation at all?

Audience: Yes, we have.

VTC: So, you know you’re trying to open your heart and extend love to other people. Well, that’s very easy when you are sitting in your classroom, and you’re not upset at anybody in that particular moment. And somebody says, “Generate metta for the whole world.” It’s so easy and we think, “Yes, I have metta for everybody. I’m so blissed out. This is a wonderful meditation.” Then you walk out of the classroom and somebody cuts you off on the highway, and your metta is gone. Even if somebody cuts you off when walking across campus, your metta is gone. “How dare they!” There’s intellectual metta that is easy and then there’s real metta that is not so easy.

Think of a person that you don’t trust. It may be somebody you know personally or it may be a politician. Think of somebody you don’t trust. Is generating metta for them easy or not? When we have a fixed view about somebody, they are this kind of person, and we have them pigeonholed. We think we know everything about them. Then it is very difficult to have any kind of love and compassion for them. We look at them and all we see are flashing red lights: “Don’t trust them!”

We have to work with our mind and discern what is going on where based on somebody else’s behavior—that they may have done once or repeatedly—we think we know everything about this person. Is that true based on somebody’s behavior for some period of time? If you total up the total number of years that person has been living and then compare it to how much time they spent doing whatever it is, is that true? We think we know them. Maybe we are exaggerating. Maybe we are not seeing things realistically. It’s good to have that idea of “Maybe I’m not being realistic.”

It’s like with the guy I was telling you about before who is kind to the prison guards. Prison is not a safe place, but he really practices kindness. He is quite amazing. And do you know what he’s in for? Double murder. Normally a person would hear that and think, “No, cut him out! He’s horrible, evil. Don’t let him around you. He’s going to hurt you. It’s not safe.” But actually, that’s not who he is. Yes, he did that, but he’s not that same person now. And even back then that’s not who he was. He was under the influence of drugs and alcohol back then. That doesn’t excuse what he did, but it helps us to understand, “Oh, he is somebody who was confused and made a mistake, but that isn’t his whole value as a human being, so I can still have an attitude of compassion toward him.”

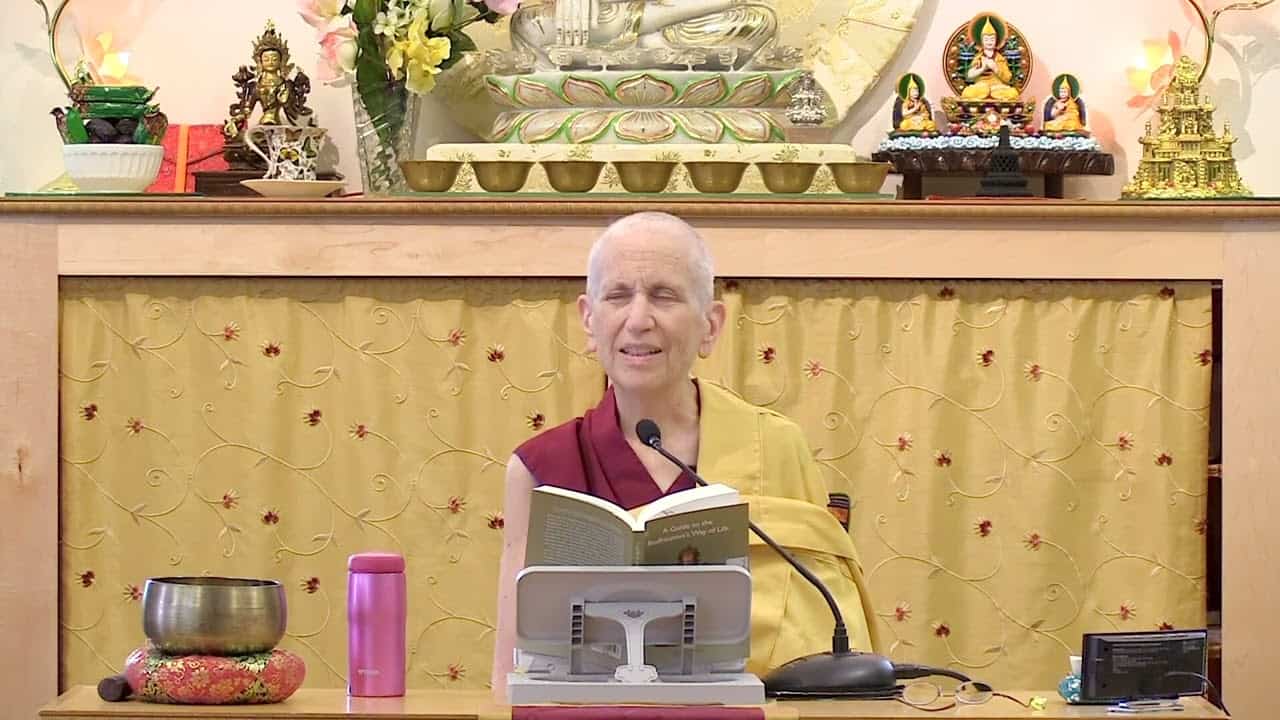

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.