Bowing and making offerings to Amitabha

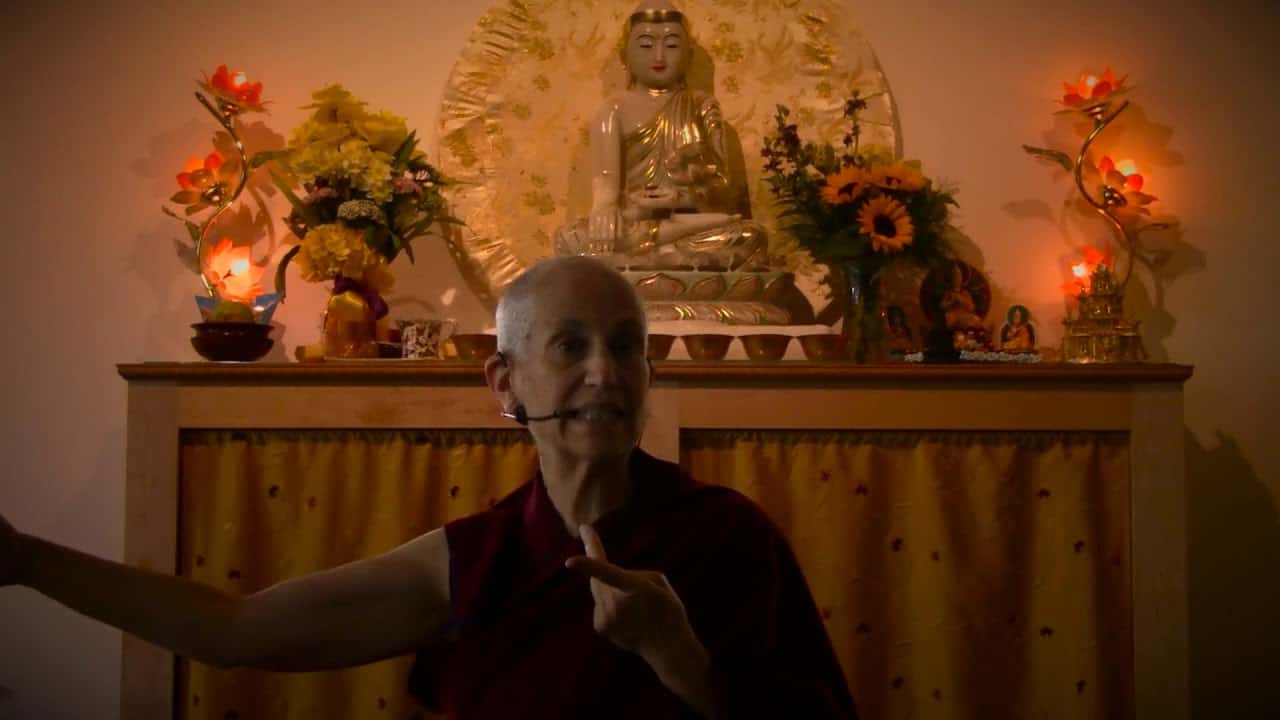

Part of a series of short commentaries on the Amitabha sadhana given in preparation for the Amitabha Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2017-2018.

- The seven-limb prayer: purification and creation of marit

- Signs of respect and humility

- Making offerings to the buddhas

I’m going to return to the sadhana for the Amitabha practice and start going through that. I had described before refuge and and bodhicitta and the four immeasurables. When you’re doing those you visualize Amitabha in the space in front of you surrounded by all the buddhas and bodhisattvas. I’ll go into the description of him a little bit later in a more expansive way because you actually visualize the whole pure land there and you’re taking refuge and cultivating the four immeasurables, and now we’re going to do the seven limbs in the presence of Amitabha and all the other buddhas and bodhisattvas in his pure land.

With the seven-limb prayer, that’s specifically for purification and creation of merit. Yesterday you may remember that one of the causes for being born in Amitabha’s pure land, purification and abandoning negative actions and then creating merit. That’s where the seven-limb prayer fits in.

In the sadhana it’s the short version, but you can also substitute the long version for it. That is in the first section in the King of Prayers. It has one or more verses for each of the limbs, so it goes into more detail. It helps you think through the meaning of the limbs a little bit more. Or you can do the short version that’s in (the sadhana) right now

The first limb is bowing (or prostration). This one is specifically for purification, but I think it also functions to help us to create merit. The idea being that when we bow to Amitabha and the buddhas and bodhisattvas we’re thinking of their excellent qualities, and by thinking of them generating the aspiration to develop those same qualities ourselves.

Bowing is a form of respect in all cultures. We make ourselves lower when we are in the presence of somebody that we respect.

The prostrations also, in Buddhism, are for purification because we usually do them, for example, in relationship to the 35 Buddhas and reciting their names and then the prayer afterwards, which is a prayer of confession and rejoicing and dedication.

There’s something, I think, very helpful about having our nose on the ground. Most of us, most of the time, don’t have our nose on the ground. We have our nose up in the air. We’re pretty puffed up with ourselves. Especially nowadays. When there are so many demands on people just to accumulate a CV and a resume, and you’ve got to be this excellent thing, and you’ve got to sell yourself. Young people are really in that position now. And so then you put on this thing of, “Oh, I’m just perfect. I can’t admit any flaws at all.” With our nose in the air. And of course it’s a big sham. And we know inside it’s a sham. But it really blocks us from getting in touch with what’s really going on. So I think prostrations is really a way of letting go of all of that.

Also it’s a way of being honest with ourselves and seeing what things we need to work on. What mistakes we’ve made, clearing them up. I’ll talk more about that with the branch of confession or repentance. Making ourselves humble so that we are receptive. And we live in a society where humility is not looked well upon, because we think of humility as weakness. But I think humility actually indicates strength, because it means you have the strength and the internal confidence to be humble inside, not have to put yourself up. When we don’t have that internal strength and self-confidence then we put on the big show of how wonderful we are and try and present this fake person to others so that they will think that we’re wonderful. Then if we think that they think we’re wonderful we might be wonderful, but we don’t really believe it inside anyway.

Prostrations kind of says, “I’m not messing with that.” And I find it very refreshing, in Asian cultures, humility is still very much honored and respected. You can see sometimes Westerners have a big problem with that. They go into Tibetan culture or Chinese culture with this kind of demanding attitude of being somebody special who deserves special attention. And, “Our views are right because we’re from a democracy,” kind of thing. And it just totally turns people off. So much so that they can’t really even hear your arguments. For example, if you’re talking about gender equality and you go in and you’re very (aggressive), they just dismiss you. If you go in and you’re humble, and you’re respectful of the tradition, and you’re courteous, and you’re patient, then you have a much greater chance of being heard in the long term. These are qualities, I think, especially in our culture, we need to work on.

The second branch is offering, and this one’s primarily for creating merit, because when we make offerings we create a lot of merit. But I also think it serves a side purpose of purifying miserliness and attachment to our own stuff. Clearly, when we’re miserly or when we’re stingy we don’t want to offer it to anybody. We want to keep it for ourselves. Stinginess is quite a painful mind. It’s very painful, having suffered through enough of it myself. Because it’s a mind with fear of, “If I give I won’t have.” It’s a mind of lack. “If I give I won’t have.” There’s a fixed pie and if somebody else gets it, I won’t have it. That whole view on life is really very, very painful, and very constricting. Whereas if we cultivated a generous attitude that takes delight in giving, then we’re happy. Because there’s always an opportunity to give, always opportunity to share, so we can be happy quite a lot during the day, and then we also create merit.

Making offerings can be in terms of making physical offerings: financial things or material things. It’s also offering service. Offering our time and our energy to support people’s good projects, or to aid them when they have a need for something to be done then to offer our time and service, and our effort to help others. And then offering protection. If somebody is in danger then to offer protection to them. To offer love to those who are grieving or whatever, who are distraught, to offer them emotional support and empathy. Then they say that the highest gift is the gift of the Dharma. To be able to share the Dharma with others. We may not be able to teach the Dharma right now but what we can do is we can talk about Buddhist points with our friends. And when our friends have problems we can share with them some of the antidotes that we’ve learned from the Dharma of how to deal with different problems. That’s very helpful with them. And then also with pets you can say your mantras out loud and your prayers out loud so that your pets and all the surrounding animals and insects hear the mantras and that’s a gift of the Dharma, it puts good seeds on their minds. That’s why often when we’re taking insects outside we’ll say mantra and blow on them and then put them outside. Why we have the kitties attend the Thursday and Friday night teachings when possible, even though they sleep through it. Like you. [laughter] No, I’m joking. Maybe.

Those are the first two of the seven branches. We’ll continue with the others later.

With the offering, it’s really nice…. In the Pearl of Wisdom, Book 1, there’s a prayer by Kyabje Zopa Rinpoche about extensive offerings where you, with your imagination, imagine huge offerings, the sky filled with offerings, the ocean full of offerings, oceans and clouds of offerings…. Anything big. Universes full of offerings. And then you offer them to the buddhas and bodhisattvas. It’s a very beautiful mediation. Sometime if you’re feeling kind of down and depressed and everything, then just the fact of visualizing beautiful things and then offering them to the Three Jewels, it uplifts your mind and it brings a lot of joy to the mind. And it really helps us.

Also, one thing that I find very helpful is if you’re attached to somebody offer that person to the Buddha. You may say, “I don’t want to offer the person I’m attached to to the Buddha.” But actually, aren’t they in better hands being counseled by the Buddha than if they’re attached to us? Which actually would help the people we care about the most? Offering them to the Buddha so the Buddha can guide them. So that’s a very nice practice and it helps free us from that possessive attachment to individuals. So, very good with that one, too.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.