Connecting with compassion

A reflection written during Sravasti Abbey's annual one-week Chenrezig Retreat.

When I see how I disconnect from the parts of myself that I dislike, I start to understand why Japan refuses to acknowledge her part in the atrocities carried out throughout Asia during the Second World War. The attachment to reputation and the fear of blame and shame are just too strong. By refusing to acknowledge the truth, however, we deny ourselves the opportunity to grieve, heal, repair and move on. We remain stuck in a limbo of pain that eats away at us, no matter how we hard throw ourselves into material growth and success.

I don’t feel angry when I think about the stories my grandparents have told me about their experience of the war. Just sad that this period of history is going unacknowledged, like so many other painful parts of Singapore’s history hiding behind the veneer of success. “It doesn’t matter who’s right or wrong,” said one of my friends. “At least just hold a funeral.”

Even as my grandmother starts to slip into dementia, her memories of the war remain strong. She remembers what it was like for the men to line up for inspection, and how those whose hands were smooth and soft were separated out, driven to the beach and shot. If their hands didn’t have calluses, it meant they were intellectuals, whom the Japanese didn’t want plotting against them. My great-grandfather was a laborer and so survived.

One day, my great-grandfather was riding home on his bicycle, when he passed a Japanese soldier and forgot to salute. The soldier asked him to get off the bicycle and slapped him. Then he made my great-grandfather carry the bicycle on his shoulders, and drew a circle around his feet. If my great-grandfather stepped out of the circle, he would be shot. He stood there until night fell. Somehow he eventually made it home, but he was so traumatized that he never dared to leave the house again.

Every family had to send people to work for the Japanese, and with my great-grandfather out of commission, my grandmother stepped up to the plate as the eldest child. She was thirteen. She did hard physical work outdoors, and received a bowl of rice each day, which she shared with her mother and younger siblings. They were so hungry they started to eat the food that was meant for the pigs, and eventually turned to eating grass.

I send Chenrezig back into time, to bear witness to the war. What would Chenrezig do, watching the men getting shot on the beach, the women getting raped, the babies being thrown into the air and impaled on bayonets? I imagine Chenrezig looking into the minds of the soldiers, and seeing that they’re just trying to be loyal subjects of the emperor. They want praise, a good reputation, power and money. The soldiers and I are not so different. Looking into their minds, Chenrezig can also see that it’s not the right time to teach them the Dharma. I mean, what is Chenrezig going to say, “For you embodied beings bound by the craving for existence, there is no way for you to pacify the attraction to its pleasurable effects, thus from the outset seek to generate the determination to be free”?

At the same time Chenrezig sees very clearly where these soldiers are going to be reborn, the kinds of sufferings they will undergo, and for how long. All this for a little bit of pleasure that doesn’t last. Chenrezig promises, “I alone will go to the hell realms and liberate you.” When the soldiers are ready, in some future lifetime, Chenrezig appears in the form of a perfectly qualified Mahayana spiritual mentor, and teaches them how to purify their negativities.

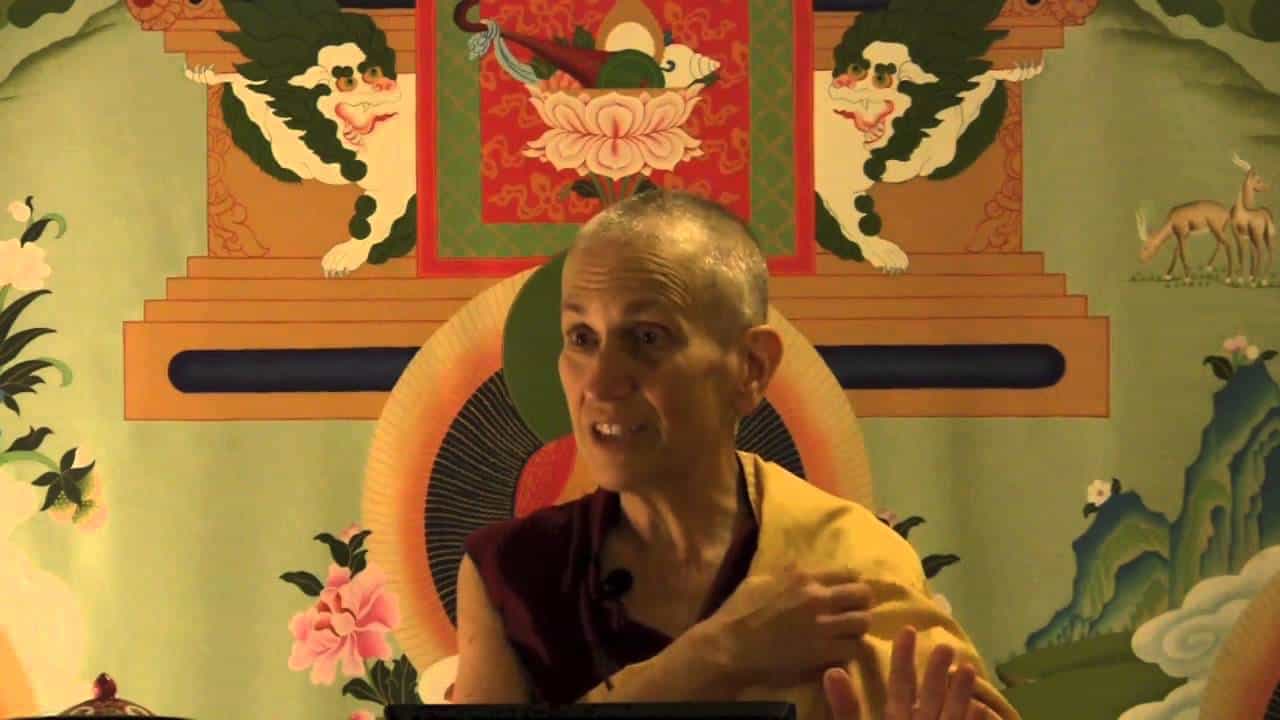

Venerable Thubten Damcho

Ven. Damcho (Ruby Xuequn Pan) met the Dharma through the Buddhist Students’ Group at Princeton University. After graduating in 2006, she returned to Singapore and took refuge at Kong Meng San Phor Kark See (KMSPKS) Monastery in 2007, where she served as a Sunday School teacher. Struck by the aspiration to ordain, she attended a novitiate retreat in the Theravada tradition in 2007, and attended an 8-Precepts retreat in Bodhgaya and a Nyung Ne retreat in Kathmandu in 2008. Inspired after meeting Ven. Chodron in Singapore in 2008 and attending the one-month course at Kopan Monastery in 2009, Ven. Damcho visited Sravasti Abbey for 2 weeks in 2010. She was shocked to discover that monastics did not live in blissful retreat, but worked extremely hard! Confused about her aspirations, she took refuge in her job in the Singapore civil service, where she served as a high school English teacher and a public policy analyst. Offering service as Ven. Chodron’s attendant in Indonesia in 2012 was a wake-up call. After attending the Exploring Monastic Life Program, Ven. Damcho quickly moved to the Abbey to train as an Anagarika in December 2012. She ordained on October 2, 2013 and is the Abbey’s current video manager. Ven. Damcho also manages Ven. Chodron’s schedule and website, helps with editing and publicity for Venerable’s books, and supports the care of the forest and vegetable garden.