Learning to live with compassion

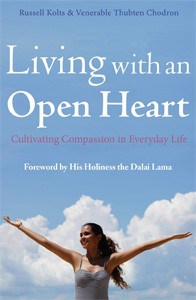

A group of long-time Dharma students from Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle meet monthly to reflect on the book Living with an Open Heart, and discuss how they can and have put the teachings in it into practice.

Part I

Sage’s summary

All agreed the book was an excellent choice for our group. It was apparent that people had taken the book and reflections to heart as we met to discuss Part I. It was a rich discussion on situations in our lives; how compassion, equanimity, courage, and fearlessness can bring a sense of happiness and well-being into our lives. We talked about those other times where—overcome by habituation and the hindrances—we were uncomfortable and constricted and disconnected from others.

We also used the reflections and examples as a discussion for how to apply the Dharma to work with our minds. These were some of the Dharma practices we talked about: taking joy in the times when we could see compassion at work, offering metta, having clear intention, seeing all beings as our mothers, exchanging self for others, creating a mind free from the extremes, remembering past lives, and dedicating merit.

Mary Grace’s reflections

I think one of our goals was to apply the practices in the book to “replace” tendencies in the mind.

From what I can remember, these were some of our examples:

- Sitting next to homeless people on the bus and replacing judging with equanimity,

- irritability replaced with pausing,

- recoil replaced with leaning in,

- seeing the other replacing fear and denial, etc.

I think our conversation on “replacing” was exceptionally rich.

Stories and examples

Each person wrote a short summary of our example, what chapter we applied in our lives, and how we “replaced” compassion for a tendency, as well as one or two things that stood out in a practical way in helping to cultivate compassion.

Leah’s story

From chapter eight—A Different Kind of Strength—I found that I was fitting this into the bodhicitta meditation sequence, specifically the step of switching my attitude toward myself with my attitude toward others. I used the teaching in chapter eight to avert the judgmental, critical, disdainful mind—often based on fear—and replaced those thoughts with the wish that the others have happiness and be free of difficulties. As I began doing this throughout the day it occurred to me that perhaps this is a beginning step in making that attitude switch because the happiness and well-being of others took precedence over my opinions.

Mary Grace’s story

From chapter six—Courageous Compassion—to tolerate difficult emotions that arise when we come into contact with suffering and those that experience it, page 22.

Visiting a good friend, who is suffering from MS, I notice at times the tendency to draw back, to shield from the experience, to close the heart. When I remember to replace this with opening my heart, smiling, and starting the conversation with a simple, “So good to see you,” the armor melts away. I consciously drop my own agenda and dialogue about her suffering. How do I know how much she is suffering? Replacing the proliferation of the story in my mind with conscious awareness of how my body and mind are responding keeps my flow of compassion. Breathing into the tight chest, making eye contact with my friend, taking moments of silence rather than giving advice. Setting boundaries about the amount of time I can spend is also part of my “replacement” strategy. “I am here for two hours (or one, or however long),” replaces the feeling of being overwhelmed with the experience. Honesty with what I can give is part of the process. (chapter seven)

Sage’s story

As my story goes, the bus is my school for reflecting on compassion. Some people on the bus make me uncomfortable. They may appear mentally ill, they may smell bad, they may capture my time with endless stories, and on and on. So the question is how to cultivate equanimity as opposed to pity with all its feelings of superiority, how to cultivate courageous compassion, how to stand next to the lovely and the unlovely. I loved chapter eight—A Different Kind of Strength—slowly and with confidence we learn a new skill set to replace the old ways of thinking that just does not work. And with that, a willingness to have empathy not only for others, but with ourselves. That is what allows change.

What is most amazing from the group was the weaving our stories with the Dharma—exchanging self for others, dedicating merit, how we all want happiness. In many ways, it felt like a glance meditation on the lamrim. One of my favorites we talked about was changing our attitudes from one of obligation, and all the shoulds that come with that for a happy mind that can dedicate the merit of what we do for the benefit of all beings—joyous effort. On that note, I will continue to send metta to as many people as I can on my way to work in the morning. I love doing that.

Part II

General discussion

We talked about how mindfulness on the body, on feelings, and on mental experiences helps us to “deconstruct” negative states such as anger and can keep us very present and aware. We also discussed how science has helped us understand the functioning of emotions as it relates to our brain. Finally, we talked about how imagery can be so helpful in switching from the self-grasping “I” and imagining how it might feel to have the qualities of compassion.

Personal reflections

- Leah has been working with the reflections at the end of the chapters each morning and has described her work with the book as transformative, because it breaks down the development of compassion into many very small, manageable steps so that it’s not just a vague thing that would be nice to develop but it’s hard to know where to start.

- Mary Grace described how she uses visual aids to help her students identify their feelings so that they can have more insight into what might be motivating their behavior.

- Sage especially enjoyed the chapter on “following your line,” and how staying focused on the intent of compassion can help us from being sidetracked by the potholes of negativity.

Part III: Cultivating compassion (October 18, 2014)

As Dharma practitioners we were familiar that many of the entries in this section come from the two meditation sequences for developing bodhicitta: the seven-part cause and effect method and the method of equalizing and exchanging self and others. We noted that it is useful to see it described in a more secular way as that can be helpful in applying it in a wide range of situation we encounter each day.

We talked a lot about cultivating love and the focus on joy in that process that is emphasized. Especially if we are getting discouraged with our progress, practicing can feel like a burden. If we focus on the joyful aspects of practice we will be more motivated to practice. One thought from the book that helps with that focus is that the reward for giving love is to feel delighted by that (not to get love in return). This also ties into what HHDL often reminds us: if you want others to be happy, practice compassion; if you want to be happy, practice compassion. We easily slip into the mistaken but very familiar and compelling notion that looking out for my own well-being is the source of happiness.

In the reflection on cultivating love it’s helpful to start with oneself, thinking of what constitutes happiness and noting that mostly it has to do with calm states of mind. Then, after imagining what that feels like, we think of others and try to replicate the strength of my own wish to be happy with the strength of my wish that others be happy. As with ourselves, we wish that others may have calm states of mind instead of the states of mind we may observe in others such as greed, anger, depression, etc. We also wish to be able to help them in future lifetimes to have such states of mind.

We talked generally about the shift of focus from myself to others and how much the entry “Rules of the Universe” addresses this. One of the rules that we could relate to is the one about others talking to me only about things of interest to me. Some of us talked about our reaction that is one of frustration or irritation when work-mates ask the commonly-asked question “Are you doing anything fun this weekend?” It’s important to stop the story that comes up for us because, as Dharma students, the activities we mostly do in our leisure time would not sound like fun to our work-mates. One of us had a very instructive experience when she asked her supervisor a question in order to connect even though she wasn’t really interested in the topic (about her wedding plans). She experienced a closer connection with her supervisor as a result than she ever had before. (It has been a challenging relationship.) We considered how much we operate from the rule that everyone should think like me, be like me, etc. and how much this drives our judgmental minds, such as when we see women college students on campus wearing high heels.

These practices help to overcome despair and have a happy mind and then it’s easier to be compassionate in that state of mind. And, kindness begets kindness so there’s often a happier response from others. When we focus on the negative we don’t even see others let alone act kindly toward them.