Refuge guidelines and karma

Part of a series of teachings on The Easy Path to Travel to Omniscience, a lamrim text by Panchen Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen, the first Panchen Lama.

- Guidelines to strengthen the practice of refuge

- Guidelines in terms of each of the Three Jewels

- Common guidelines

- The four general characteristics of karma as guidance for how to live

- Purification of non-virtuous actions using four opponent powers

Easy Path 15: Refuge guidelines and karma (download)

I wanted to talk about the guidelines for the practice of refuge because the more we can train in these guidelines then the stronger our refuge is in this life. The stronger our refuge is in this life the more likely it is to be present when we die, and thus, the more likely it is for us to meet the Buddha’s teachings in future lives. All of that is quite important.

We normally take refuge at the beginning of any kind of Buddhist practice, whether we are meditating or doing some kind of rituals or whatever. No matter what we are doing we always take refuge and generate bodhicitta at the beginning. Then there also exists a ceremony for taking refuge where you recite the refuge formula after one of your teachers. In that way you formally take refuge and you make a connection with the whole lineage of masters that goes back to the Buddha—from your teacher, back to their teacher, and then back to the Buddha. It is a very nice ceremony to do. It’s completely optional and when people want to do that they usually make a request, and then we do the ceremony.

I know the Singaporeans are watching this evening and maybe the children are there, too. Are any of the kids there? When they were here at the Abbey the whole family took refuge, the parents and the kids, everybody together, so this is a real good teaching for the kids. If the kids aren’t there maybe they can watch the video.

Audience: What page are we using in the text?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): It’s the section under refuge. If you look in the section under refuge, the English text is on page 10. This text is extremely short. I’m bringing in a lot of material from other places, but the visualization we just did came right out of this text. In the refuge ceremony we also have the option of taking the five lay precepts at the same time; you can take one, two, three, four, or all five. When you take the precepts, you take them for life. That is very nice because you commit yourself to a certain way of behavior and that gives you a lot of inner strength not to do what you’ve decided you don’t want to do anyway. Before we get into the five precepts, let’s just go over the guidelines for the practice of refuge. If you have the blue prayer book—the Pearl of Wisdom, Book One—it is on page 88.

Refuge guidelines

Commit yourself wholeheartedly to a qualified spiritual mentor.

This is an analogy to taking refuge in the Buddha. We don’t have the karma to meet the Buddha, so we follow the guidance of our spiritual mentor, and we want to check the qualities of that person. As you know, I talked in great length about it at the beginning of this series of teaching. We choose our teachers; you don’t rush into this and you don’t have to push yourself to have a teacher or many teachers. But then when you do make that connection, you try to make it a wholehearted connection rather than one where you think, “Well, this is my teacher whenever they say what I want to hear, but I’m not so sure if they’re my teacher when they point out my faults.” That is not the proper way to do it.

Listen to and study the teachings, as well as put them into practice in your daily life.

This is an analogy to taking refuge in the Dharma. It’s the essence of what we need to do, so we don’t think instead: “Oh, I’ve taken refuge, now the Buddha is going to take care of me and do everything for me, and I don’t have to do anything,” or “Now that I’ve taken refuge I’m a Buddhist, so all I do is chanting ceremonies and I just chant all the time,” and feel that is good enough.

No, chanting is good if you know how to think while you’re chanting, but in order to know how to think while you are chanting you have to receive teachings and reflect on the teachings. Otherwise, it’s chanting like a tape recorder, which they have in many places now. They have the little machines that you turn on and they chant, but those little machines don’t accumulate any merit. [laughter] They chant a lot but no merit. Similarly, if we don’t think properly, we might chant a lot, but the merit is uncertain. So, we really have to listen to and study the teachings, because that is how we are going to maintain and deepen our refuge.

Respect the Sangha as your spiritual companions and follow the good examples they set.

This is an analogy to taking refuge in the Sangha. Here “sangha” means the monastics—the monastic community in particular, or any individual who has realized emptiness directly. So, we respect the monastic community as our spiritual companions, and we follow the good example that they set. These are people who keep precepts, so hopefully they are practicing their precepts well and becoming a good example. When you see the sangha misbehaving don’t follow that, because there are naughty monastics. Don’t say, “Well, I saw somebody else do blah blah blah, so it must be okay for me to do it, too”—even though you know that it is against what the Buddha prescribed for his disciples. Don’t think like that.

Avoid being rough and arrogant, running after any desirable object you see and criticizing anything that meets with your disapproval.

What are we going to talk about with other people then if we’re not rough and arrogant, running after all the desirable objects and talking about them, and also criticizing everything that meets with our disapproval? If we don’t talk about everything we want and how we’re going to get it, or how we got it, or all the mean things people are doing, or how things aren’t going the way we want, then what are we going to talk about? This is a really strong reminder to watch our speech and, of course, to watch our minds and the kind of thoughts that are going on in our mind. This is not so easy.

Be friendly and kind to others.

We all want to do that of course. Unless people are mean to us, then we want to cause some suffering back. This is saying to be friendly and kind to others. It doesn’t matter how they treat you; be more concerned with correcting your own faults than with pointing out the faults of others. “Oh my goodness, what kind of guideline is that? Being more concerned with my own faults than with pointing out the faults of others?” Again: “What am I going to talk about? What am I going to say to people after I say good morning if I don’t tell them what they should be doing and what they’re doing wrong? What else am I going to say to them?”

You say, “Good morning,” and then scowl. [laughter] “You know, you haven’t done your chores from three weeks ago. The dishes are still dirty in the sink. Are you going to go up to the forest today? How come you haven’t finished this report? The boss wants it now. Did you do all the banking? How come you’re always lazy and you don’t do these things?” This is what so much of our conversation with people—especially our family—is, isn’t it? This is true especially with your children. So, this is saying to be more concerned with correcting your own faults than with pointing out those of others.

Now I see all the children nudging their parents: “Look mom and dad—be aware of your own faults.” But parents, you nudge your kids and say, “Okay, now you look at your faults and stop yelling at me and blaming me and being rude to me.” Both parties have to do this. Kids, you can’t just point at your parents, and parents, you can’t just point at your kids. It goes both ways.

We’re experts at identifying other people’s faults plus everything that they should do that they haven’t done and everything they did that they shouldn’t have done, aren’t we? We need to train our minds to be more aware of ourselves rather than picking faults with other people, but that’s a tall order, isn’t it? What I advise is every time you have the thought “I need to tell somebody to do this a different way,” turn the mirror towards yourself and say, “And how am I behaving and what haven’t I done that I should have done?” Instead of having the light shining out there on everybody else with what they’ve done and left undone, turn the mirror on yourself: “What about me? What about my behavior?” Because we can’t control everybody, can we? The only one we can possibly manage to change is ourselves, so that’s where we need to put the emphasis.

As much as possible avoid the ten non-virtuous actions.

This is killing, stealing, unwise and unkind sexual behavior—the three physical ones. Then the four verbal ones are lying, divisive speech, harsh speech, and idle talk. And then the three mental ones are coveting, malice and wrong views. As much as possible avoid those and take and keep the eight precepts—specifically the eight Mahayana precepts whenever you can. It’s good to do that on new and full moon days, or if that’s not so convenient because you’re at work, then maybe do every other Sunday or something like that. Or when you’re feeling kind of like your practice isn’t going anywhere, then it’s good to take precepts. It really perks up your practice, and you accumulate so much merit when you do that.

Have a compassionate and sympathetic heart towards all other sentient beings.

This is an important guideline if we want to deepen and maintain our refuge. It’s about having a good relationship with sentient beings. Don’t think, “Oh, the Three Jewels and my teacher are wonderful, but sentient beings are idiots.” No, if we are to keep our refuge pure, we have to have a compassionate and sympathetic heart towards sentient beings—all of them.

Make special offerings to the Three Jewels on Buddhist festival days.

Make special offerings to the Three Jewels on Buddhist festival days. Specifically, this is on new and full moon days and then on the Four Great Days. At least in the Tibetan calendar, these are the Great Days:

- The full moon of the first month, which is the Day of Miracles when Buddha defeated the heretics.

- Vesak Day, which is the anniversary of the Buddha’s birth, enlightenment and passing away.

- Descent from the God Realm, which is after the Varsa (the rainy season retreat) finishes in the autumn. It is said that the Buddha went to the God Realm to teach his mother during that time, and this is the anniversary of the day that he descended back onto Earth.

In the Chinese calendar we also have the birthdays of all the various bodhisattvas to add on to that, and then I think there are probably a number of other days too in the Theravada calendar.

Guidelines in terms of the Three Jewels

First having taken refuge in the Buddha who has purified all defilements and developed all excellent qualities, do not turn for refuge to worldly deities who lack the capacity to guide you through all problems.

“Worldly deities” means things like seances and trances and things like that. In the Tibetan tradition specifically, there is one spirit called Dolgyal Shugden, and people should really stay away from that practice because it’s a spirit and taking refuge in that is not going to benefit you. We really need to keep our refuge pure in the holy beings who have the realization of emptiness, not in spirits who can have all sorts of different motivations, just like human beings can.

Respect all the images of the Buddha. Don’t put them in low or dirty places, step over them, point your feet towards them, sell them to earn a living, or any of these kinds of things. When you look at different Buddhist statues, don’t discriminate by thinking, “This Buddha is beautiful, but this one is ugly.” You can say the artistry here is good; this artistry isn’t so good. Don’t treat expensive and impressive Buddhist statues with respect while neglecting those that are damaged or less expensive. People often like to show off their altar: “Oh, here’s my altar, look. Do you know how much this statue cost? I got it from here and there. And look at my Thangka there—I got that at a really good price, and the most famous artist in Dharamsala painted it.” We treat these holy objects as ordinary possessions, and we brag about them in order to create a good impression with other people, and that is completely missing the point. That is the opposite of what we should be doing.

Having taken refuge in the Dharma, avoid hurting any other living being.

The bottom line is to avoid harming any living being. If you can’t do any other Buddhist practice, do this. Also, respect the written words that describe the path to awakening by treating the text respectfully—putting them in a high place. We don’t put our Dharma text on the floor; we put a table, or a cover, or something like that under them. We don’t put our coffee cups and our malas and other things on top of our Dharma books. We treat them very respectfully. We keep them on a separate shelf and keep them up high.

Actually, they say that your Dharma text should be placed higher than the Buddha statues because it’s through the Buddha’s speech that the Buddha helps us the most. Usually we put our statues on the top and the books on the shelves underneath. It actually should be that the books are higher or the books can be on the side but up high. If you have old Dharma books or papers—old notes, papers with Dharma words on them—then either burn them or recycle them. But don’t just throw them in the garbage with all your other stuff, like the orange peels and the baby’s diapers. That’s not very respectful of the material that outlines the path to enlightenment for us.

Having taken refuge in the Sangha, don’t cultivate friendships with people who criticize the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha or people who have unruly behavior and do many negative actions. By becoming friendly with such people you may be influenced in the wrong way by them.

However, that does not mean you should criticize them or not have compassion for them. The reason for this guideline is, as my parents taught me, birds of a feather flock together. You remember that? Did your parents say that to you? It means that you become like the people you hang out with. It’s not just parents wanting their kids to hang out with good people, but parents need to hang out with good people, too—because who your friends are influences how you act and how you think.

If you become very dear friends with somebody who criticizes the Buddha, Dharma, or Sangha, because you have affection for that person and you trust them, then you’re going to start taking their criticisms to heart, and it will cause a lot of doubt in you. That doesn’t help you practice at all. Or if you hang around people who don’t keep very good ethical conduct and follow their advice, you create lot of destructive karma. It’s not helpful to be close with people who are trying to get you involved in shady business deals, who are encouraging you to lie in order to close a business deal—people who think in a worldly way they’re trying to help you but are not acting very ethically.

Sometimes this even involves our relatives. So, in these cases we’re polite, we’re friendly, but we don’t establish really close relationships. We can still chit-chat and be polite. We still have compassion for them, but we just don’t become real good friends.

Also, respect monastics as they’re people who are making earnest efforts to actualize the teachings. Respecting them helps your mind because then you appreciate their qualities, which makes you more open to develop your good qualities. Even respecting the robes of ordained people will make you happy and inspired when you see them. That can sound rather funny, you know—“the robes”—but a New Yorker friend of mine told me a story. He lived in Dharamshala for some time and then he went back to New York, and there were no monks and nuns anywhere around. He was really missing his Dharma friends, then one time in the New York subway, he saw a monk on another platform, and he got so excited because he saw the robes. It was like: “Wow, there’s a monk! There are the robes!” He forgot about his subway train and went dashing to the other platform to talk to this person—that’s how happy he was to see another practitioner.

Common Guidelines for the Three Jewels

Being mindful of the qualities, skills, and differences between the Three Jewels and other possible refuges, repeatedly take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

Think of the different qualities of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha and how those different qualities can benefit you, because each of them has a different way of benefiting you. Or if you’re having interreligious dialogue, think of the qualities of our objects of refuge and then think of the qualities of the objects of refuge of other religions and compare them. That helps you to deepen your refuge.

Remembering the kindness of the Three Jewels and making offerings to them, especially offering your food before eating.

It’s very good if you can have a shrine or an altar in your house, and then the first thing we can do every morning is to make offerings. It’s a nice practice to clean your altar and then offer food or the water bowls or flowers—whatever you have. It’s a very nice way to start the day, and it’s a nice activity for parents to do together with their kids because kids like to pour the water and offer the food. One family that I stayed with, every day the little girl made an offering to the Buddha and the Buddha gave her a sweet everyday. Now she is the director of a Dharma Center. She grew up as a Buddhist; her mother taught her very well.

So, we can offer our food before eating. If you’re out in a restaurant or with other people who aren’t Buddhist, just let them talk and—in your mind—do the refuge prayer. Whenever you eat anything, at least say, “Om Ah Hum,” or one of the verses and offer the food.

Being mindful of the compassion of the Three Jewels, encourage others to take refuge in them.

We don’t need to be closet Buddhists. Some people are afraid at work when people ask, “Oh, and what religion are you?” They change the subject. You don’t need to advertise it, but you also don’t need to be shy about it. I think it can actually be quite good for other people at work to learn that there are people of diverse religions and different beliefs, and we can all get along. It can also be a very helpful example for other people at your workplace.

Some years ago when I was teaching in Seattle, there was one woman who came to the teachings. She had red hair, and she also had lupus, so she was in a wheelchair. She had a temper, so they used to call her hellfire on wheels. She had a reputation. She worked for the FAA, and as she was practicing the Dharma, she began to calm down. She didn’t get as angry. She was much more agreeable to people, so people at work started asking her what she was doing. She had the set of 100 and however many tapes of the Lamrim teachings that I gave back in the ’90s. One of her colleagues listened to the whole set of Lamrim teachings because he was so impressed with the changes that he had seen in her.

You really never know the effect you’re going to have on other people when you say you’re a Buddhist and then people see that maybe you’re calmer than other people, or they can see the change in you. It gets them interested. So, when it says to encourage people to take refuge, we don’t stand on the street corner but we don’t hide things either. Sometimes you may have friends who are not Buddhist who are going through some kind of difficult time in their lives, and you can talk to them about the Buddha’s teachings and the Dharma antidotes to certain defilements without mentioning any Buddhist language or anything like that. If they’re really angry you can talk about Dharma antidotes to anger or you can give them a book.

I had one friend whose sister was a Jehovah’s Witness, so she tended not to talk with her sister much about religion, but one day she forgot and she left her Dharma book out. When she came home, her sister had read part of the book and said, “You know, a lot of what we believe is really similar when it comes to ethical conduct and treating people well and forgiveness.” So, sometimes you just leave Dharma books around. People may pick them up when they’re interested, or if they have some problem. Maybe they had been seeing Working with Anger or Healing Anger on the bookshelf for three years, and now they’re really angry, so they may just see what that book has to say.

Remembering the benefits of taking refuge, do so three times in the morning and three times in the evening by reciting and reflecting upon any of the refuge prayers.

When you first get up in the morning, take refuge. Before you go to bed at night, take refuge. Also, you should generate your motivation first thing in the morning and generate your motivation before you go to sleep.

Do all actions by entrusting yourself to the Three Jewels.

Really have refuge in your mind, whatever you’re doing.

Don’t forsake your refuge at the cost of your life or even as a joke.

This means to really cherish your relationship with the Three Jewels, and to make it a precious thing. Then if you want to, if you have an opportunity, you can also do the refuge ceremony.

Those are the guidelines that you practice after you take refuge in a ceremony. Then if you want to, you can also take the five lay precepts or any of them. Those precepts are to abandon killing, abandon stealing, abandon unwise or unkind sexual behavior, abandon lying, and abandon taking intoxicants.

Before we go on to the next thing, are there any questions about what we’ve covered so far?

Audience: I realized I wasn’t clear on something in the refuge. The precept about not lying. I took that as not lying in general, but it seems it’s more about not lying about spiritual things?

VTC: The way you break this precept from the root is if you lie about spiritual attainments. If you do that then you’ve broken it from the root. Other kinds of lies are not as serious as that one, but they still fall under that precept of abandoning lying.

Audience: I was going to ask you to run through the actual refuge ceremony.

VTC: I don’t run through it; I give the refuge. Here’s the outline of what happens in the ceremony:

- You come in and you bow.

- The teacher helps you generate the motivation.

- Then you say this one verse three times after the teacher.

- Then the teacher goes through these guidelines on refuge.

- Then you dedicate the merit.

- Then you bow again.

Audience: I was thinking about forsaking refuge even at the cost of your life—there’s a fuzzy thing in my mind about Tibetans in Tibet, for example, who can’t or are punished for outward displays of it. And also some monastics I know who had to grow their hair out and wear lay clothes if they wanted to visit Tibet at a certain time. It has always made me wonder where is the line between actually forsaking your refuge and protecting yourself?

VTC: What is the meaning of forsaking the Dharma, and what about situations where—for example, during the Cultural Revolution be you in China or Tibet when Buddhism was being suppressed—you could not practice openly? Even nowadays monastics don’t necessarily wear their robes when they go visit Tibet. Those are changing the external things, but in your heart your refuge can still be just as strong. So, abandoning your refuge means in your mind—like maybe you made very strong prayers for some worldly aim, it didn’t happen and then you say, “Well, the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha don’t come through.” Abandoning your refuge is a mental thing.

In cases where there’s danger, where you could be imprisoned or killed, it’s not abandoning your refuge to just change some outer aspect in order to stay alive. I know one Tibetan monk whose family had been kind of wealthy so the Communists had taken over his house, and he was imprisoned in it. The house was converted into the local jail, and he did a retreat the whole time that he was imprisoned. He couldn’t have a mala and he couldn’t move his lips, but he would just sit there and approximate how many mantras he had said according to where the sun was. He did many retreats. On the outside it looked like he was doing nothing, but he certainly hadn’t abandoned his refuge.

Audience: What if his captors had asked him to verbally denounce the Triple Jewels?

VTC: Yes, if you verbally denounce the Three Jewels then that certainly is abandoning your refuge—unless it’s under coercion, like somebody’s going to kill you or something like that. But again, in your heart you don’t necessarily have to do it—whereas people can abandon their refuge without saying anything. And without doing anything, they can abandon their refuge.

Audience: A monk mentioned that you can adopt the precepts simply in front of a Buddha statue. Can you really do that? When and how can we take the precepts?

VTC: In the Tibetan tradition anyway, you usually take the precepts during the refuge ceremony, so you make a request to one of your teachers to give the refuge ceremony. Maybe there’s not the opportunity to do the refuge ceremony real quickly, so then you can make a strong determination in your own mind to keep the precepts, and then later when you have the chance to actually take them then do that.

Audience: I want to make sure I have this clear. When we do the abbreviated recitations, first you have the refuge field, and then you have a merit field, and then you do the merit field with the seven limb prayer?

VTC: The way we’re doing it here, we are just using the refuge field and the merit field. We’re just using one of them. If you are doing a longer practice, like the Jorchӧ, then you do the refuge field, absorb that, and then you generate the merit field and do the seven limbs that way. But here we’re just going through things in an abbreviated form.

Audience: What about sarcasm, in terms of refuge?

VTC: What about sarcasm? Like being sarcastic about the Three Jewels?

Audience: No, being sarcastic in general to people.

VTC: Oh, being sarcastic in general.

Audience: There’s one about being kind to people.

VTC: Well, there’s a kind of sarcastic humor where you’re just being humorous and your motivation is just humor, and then there’s the kind of sarcasm where your mind really is derogatory and you want to tear somebody down. Clearly that involves being arrogant and unkind. The first one where it’s a certain kind of humor: if you don’t really have anything real bad in your mind, it’s kind of like the way Americans talk about politics. We are often very sarcastic, aren’t we? But it’s just kind of the way we talk. Some people may have a really negative, angry, disturbed mind when they do that, and other people may just do it because it’s what we do. We’re all kind of cynical about our politics together. What do you think? Do you think that’s really negative when you get like that? You look perplexed.

Audience: I think it’s a sign of a deeper wound.

VTC: It’s definitely a sign. It’s a sign that we are very disappointed. We are very disappointed in our leaders, and so we make these jokes about them and exaggerate things. It is also very much part of our culture. In the newspaper what do you have? There are all these political cartoons and some of them are quite clever. [laughter]

Audience: I really agree; it is part of American culture. I’ve had American expatriate friends in Singapore who say that nobody understands the sarcasm. Singaporeans are like, “huh?”

VTC: Yes, for sure, because Singaporeans would never talk the way Americans do—never. And so, when Americans do it they are probably rather shocked.

Convictional faith in the law of karma and its effects

We’re going to go on to a different topic now. We just finished the topic of refuge. We’re now on to the next topic, which is cultivating faith in the form of conviction. So, this is having convictional faith in the law of karma and its effects. We’re going to contemplate karma very briefly before we have the broader explanation. The Conqueror’s scriptures say:

From a cause that is the practice of virtue only a result of happiness can occur, not one of suffering. And from a cause that is non-virtuous only a suffering result can arise, not one of happiness.

Although one may perform only minor virtue or negativity when either fails to encounter an obstacle it gives rise to the result of great magnitude.

If you perform neither virtue nor negativity you will experience neither happiness nor suffering.

If the virtue or negativity performed encounters no obstacle the action performed will not go wasted; it is certain to produce either happiness or misery.

Furthermore depending on its recipient, support, object, and attitude a karmic action will be more or less powerful.

Having generated faith based on conviction in this, may I strive to do good, starting with minor virtues [the 10 virtues and so on], and may my three doors of action [body, speech, and mind] not be sullied by even the slightest non-virtue [such as the 10 non-virtues].

Then we request the Buddha:

Guru Buddha, please inspire me to be able to do this.

In response to your request to the Buddha, five colored light and nectar stream from all the parts of his body into you, entering you through the crown of your head. They absorb into your body and mind and into the bodies and minds of all sentient beings, purifying all negativities and obscurations accumulated since beginningless time, and especially purifying all illness, spirit interferences, negativities and obscurations that interfere with generating convictional faith in karma and its effects that includes correctly producing good deeds and abstaining from bad deeds.

So, think that all your resistance or obstacles to the topic of karma and its effects are completely erased and really have the confidence that you can discern virtuous actions from non-virtuous ones, engaging in the former, abstaining from the latter.

Your body becomes translucent, the nature of light and all your good qualities, life span, merit and so forth expand and increase.

Think in particular that having cultivated convictional faith in the law of karma and its effects, think that a superior realization of abandoning negativities and the correct practice of virtue has arisen in your mindstream and in the mindstreams of all the sentient beings around you.

Although you may strive in this manner, if due to the feebleness of your antidotes and the strength of your afflictions you are sullied by non-virtue, then do your utmost to purify it by means of the four opponent powers and abstain from it henceforth.

Review

Let’s review what we’ve done so far. We started out in the lamrim with learning how to rely on a spiritual mentor, and then we went into depth about our precious human rebirth so that we can see the great fortune and opportunity we have. After that came the meditation on death and impermanence, so we remember that our good opportunity does not last long and that we shouldn’t waste it by engaging in the eight worldly concerns and in trivial pursuits.

Thinking about death leads us to contemplate: “Where am I going to be reborn afterward?” When we look at our lives we see that due to our actions there’s danger that we will be reborn into an unfortunate rebirth because we have done many of the 10 non-virtue. So, we become really concerned about the possibility of being born in a lower realm because it’s hard to get out of those realms, and it’s very difficult to create virtue once you’re born in them.

That really kind of shocks us and we realize, “Wow, I’ve got to get it together. I need a reliable refuge who can teach me what to practice and what to abandon. I need a refuge who can teach me what I need to do to get out of cyclic existence, and what I need to do to stop the possibility of being born in the lower realms, and what I need to do in order to create the causes for a good rebirth or for liberation.”

So, we take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha as our guides who are going to show us the way. And then the first thing that they teach us about is the law of karma and its effects—in other words, actions and the results of our actions. When we learn about karma and its effects, we really gain the ability to determine what we’re going to be reborn as, because we realize that we have the choice about what actions to do, what actions to abandon, and that we need to slow down and learn to discern virtue and non virtue very well and then practice virtue and abandon non virtue. And if we’ve created non virtue in the past then to purify it so that it can’t ripen in the future.

This is the first thing that the refuge objects teach us when we take refuge. The topic of karma and its effects is quite a large topic in the lamrim—the stages of the path—so we’ll try to hit on some of the most important points. This will involve a lot of future study for us as well. In the verse that we just did, it starts out talking about the four general characteristics of karma, so we’ll go through those. I found personally that when I was learning Buddhism at the very beginning, learning about karma was just immensely helpful in terms of figuring out how things function and for giving me some guidance about how to live.

The first general quality of karma

The first general quality of karma is that when we experience suffering it comes from negative or destructive karma; when we experience happiness it comes from virtuous karma. And it’s never the opposite. It’s never that the experience of suffering comes from virtue and the experience of happiness comes from non virtue. It’s never that way, and here’s something that leads us a little bit into the topic of emptiness and dependent arising in that what we delineate as virtue and non virtue, none of that is inherently virtuous or inherently non-virtuous. Rather, things are indicated virtue or non virtue—you can use the word wholesome and unwholesome if you prefer those—they’re delineated in that way based on the results that they bring.

In theistic religions it is usually the Creator who makes up the set of rules and delivers it to human beings and says, “Do this and don’t do that,” and “If you do this stuff that I told you not to do I’m going to punish you and send you to hell, and if you do this stuff that I told you to do I’m going to reward you and send you to heaven.” That’s the usual way it is in a theistic religion, so it’s the Creator who set up the rules.

In Buddhism the Buddha did not make up the rules because the Buddha is not a Creator. The Buddha only described how things function. Because the Buddha had these tremendous psychic powers, so when he saw beings experiencing happy results, he was able to look and see what kind of cause they created, usually in a previous life, that led to this particular happy result. And those different causes that later ripened into happy results, they were called virtue or wholesome actions.

When the Buddha saw sentient beings suffering, and again through this clairvoyance he was able to see the actions that they did that brought that suffering, those actions were designated non virtue or unwholesome actions. Here we see that the Buddha did not make up the law of cause and effect; he only described it. And we see that virtue and non virtue are merely designated in relationship to the results that they bring. So, nothing is inherently one thing or the other. But it still functions, and if you create non-virtue it’s going to bring suffering, never happiness. If you create virtue it will bring happiness, never suffering.

This is really teaching us that our actions have an ethical dimension because so often we’re just going through the day and we’re not thinking, “Gee, what I am doing has an ethical dimension that’s going to influence my future lives and what I experience in the future.” Or if we do think anything about our actions having a result, we are only thinking about the immediate result that happens in this life. But that’s very short term because very often the actions we do have an immediate result in this life, but their karmic result is what happens in future lives. It’s not always so simple to know what’s going on. That’s why we need these kinds of instructions. So, that’s the first quality of karma.

The second quality of karma

Although one may perform only minor virtue or negativity when either fails to encounter an obstacle it gives rise to a result of great magnitude.

A small cause may lead to a big result, and the analogy here is that you can have a small seed and when you plant it, it leads to a big plant. When you work out in the forest, you see these enormous cedar trees, or sometimes these huge doug firs or grand firs, and then you think it all started with one itty bitty seed. Then you look down beneath your feet and there’s these itty bitty little trees poking up and then some others that are bigger and others that are still bigger and then finally this huge tree that’s 90 years old or whatever—but it all started from something small.

The idea here is that we should not downplay or disregard small actions, either small positive actions or small negative actions, because unless they encounter an obstacle then they will increase. Their power increases; the result that they’re going to bring increases when they’re in our mindstream. We might sometimes say regarding little things: “Oh, it’s just a small negative action.” Like we say, “Oh, that was just a little white lie. Little white lies don’t count. It’s such a small thing, nobody will even remember it.” But if that small thing stays on our mindstream and if we don’t purify it, it can grow until it becomes a big result.

Therefore, we should be really aware and not do even small negativities, let alone big ones, if we care about ourselves. And then it’s the same thing regarding small virtuous actions. Sometimes we say, “Oh, that’s just a small virtue; I’m kind of lazy, so I won’t do it. I don’t need to set up my altar today and make offerings; putting a piece of fruit on the altar for the offering to the Buddha is so small, it doesn’t matter if I don’t do it.” Well, when you think that a small action like that could bring a huge result then you don’t want to be lazy in creating small actions, because you realize that you miss out on the possibility of creating causes that could lead to really big results.

The third quality of karma

If you perform neither virtue nor negativity you will experience neither happiness nor suffering.

That is often worded as, “If you don’t create the cause you don’t experience the result.” Very often it happens that when something unpleasant happens to us we ask, “Why did this happen to me?” Well, if you understand karma it’s because I created the cause—that’s why it is happening to me. That is why I’m experiencing the result. So, we don’t need to sit there asking, “Why? Why me? Why do all these horrible things happen to me?” Well, I created the cause, so why get angry and upset about it if it was due to my own bad behavior?

When it’s something wonderful, we never ask, “Why me?” Did anybody think today: “Why was I able to eat lunch?” Did it even enter your mind to ask, “Why was I able to eat lunch today when so many people on this planet weren’t?” We don’t even think about things like that, do we? And that’s just a small fortunate thing that we experience in our life that we take so much for granted, but all of that comes through our actions, too. When you understand this—that small things can lead to big results and that if we don’t create the cause we don’t get the result—then we want to make sure that we don’t create the cause for pain and we do create the cause for happiness because those are the results we want.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama is always telling people that you’ve got to do more than just sit there praying, “Oh, may I have happiness in my life. Oh, may I have children. Oh, may I be rich. Oh, may my kids do well in school. Oh, may the world be at peace.” You have all these prayers, and that’s very nice, but prayers are just wishes—we’ve got to do more than that and create the cause to experience the kind of results we want.

If we want wealth, instead of praying, “May I be rich,” be generous because generosity is the cause of wealth, plain and simple. It’s not just: “Buddha, Buddha, Buddha—may I be rich!” It’s: “How can I make offerings? How can I share what I have with other people?” We have to create the cause. If we don’t create the cause, it’s like not planting seeds in the garden and only standing over it and praying, “May the broccoli grow. May the daisies grow. May we have wonderful cabbage and cauliflower.” But you didn’t plant the seeds in the garden—it’s that kind of thing.

If we want happiness we have to create the cause, and if we don’t want suffering then we have to be sure that we don’t create that cause. You can see this difference in things—like sometimes in some cities they’ll have everybody in certain businesses on one street. In India it is like this a lot. It’s a little bit different here, but in India, all the people who do car repairs are on one street and some people do really well and other people on the same street don’t do very well. And some of this can be due to the kinds of causes that they created in the past. Some people created the causes to have lots of customers and good employees, and other people created the cause to have employees that steal from them and maybe a bad location so that they don’t get many customers.

It’s a similar situation with the different events that happen on the planet. If we’re there during an event that happened it’s because we created the cause to be there. If there’s an earthquake in some place, we created the cause to be there. If we have the fortune to go to His Holiness’s teaching somewhere, we created the cause to be able to go. So, if you don’t create the causes then those results aren’t going to come.

The fourth quality of karma

If the virtue or negativity performed encounters no obstacle, the action performed will not go wasted. It is certain to produce either happiness or misery.

That means that once we’ve created the cause, the result is going to come unless there are things we can do to prevent a result from coming. In the case of virtuous karma we have created, if afterwards we get angry or we generate wrong views, that impedes the ripening of our virtuous karma. That’s one reason we dedicate the merit. It’s like protecting it—putting it in the bank, so it won’t get destroyed if we get angry or generate wrong views. This is also why when you’re getting angry it is very good to stop and ask yourself: “Is getting angry worth destroying all my karma? Is it really worthwhile to get angry at this particular person who did whatever they did if it means that I’m destroying my virtuous karma or I’m impeding my virtuous karma from ripening?” That kind of jolts you and you go, “Well no, my anger doesn’t hurt the other person; it just hurts me.”

Review of the four opponent powers

In the case of negative actions the way we impede them from ripening is by doing purification practice with the four opponent powers. The first of the four opponent powers is regret. This is very different from guilt—don’t confuse regret and guilt. Guilt is when we take responsibility for what is not our responsibility. Guilt is also when we beat ourselves up over something that we don’t need to beat ourselves up about, or maybe we did make a mistake but then we make such a big deal about it—putting ourselves as the center star and how terrible we are—that we just get involved in another self-centered trip. “Oh look at me! I did this! I committed this negative karma, how terrible! Oh I’m such a sinner, this is awful! I’m going to go to the lower realms! Oh I feel so guilty, I feel so bad. I can never show my face again to this other person after the negativity I created.” We go on and on and on. And who’s the star of it all? Me! It’s me and how terrible I am, and this is not a virtuous state of mind.

Guilt, from a Buddhist viewpoint, is an affliction that needs to be eliminated. That is very different than a virtuous sense of regret where we look and we say, “Oh, I made a mistake and I created some negative karma. I harmed somebody else. I really regret having done that and I’m going to do some purification practice now to remove or lessen the impact of that action.” Regret is done with a sense of wisdom. Guilt is just this emotional thing, and it is very interesting how in a Western culture, somewhere in the back of our mind there’s the thought: “The guiltier I feel, the worse I feel, the more I am atoning for the evil thing I did, so I’ve got to make myself feel totally horrible by criticizing myself and feeling full of shame and full of guilt because the worse I feel, the more I’m atoning for what I did.” That’s how the argument in our mind goes. That is an incorrect argument. Making ourselves feel lousy does not purify our negative karma.

Then after regret, the second opponent power is taking refuge in the Three Jewels and generating bodhicitta. The third is developing a determination not to do the action again. And the fourth is doing some kind of remedial behavior that’s virtuous. That’s the way to stop the ripening of the negative karma—not by making ourselves feel awful. So, you need to be aware if you have the habit in your mind of dramatically berating yourself: “I feel so awful, so regretful because I did this horrible thing! I am totally evil! I can never show my face again!” Stop the drama and just do the four opponent powers—stop the drama. We don’t need that kind of drama, but we do need to do the four opponent powers.

We like drama, don’t we? [laughter] Because when there’s drama, there’s me. I exist when there’s drama. “Again, yeah—fell into my hole again.” So, regret is the first one; for the second one, we restore the relationship by generating positive attitudes towards whoever it was we harmed. If we have harmed our spiritual mentor or the Three Jewels, then we take refuge. If we have harmed sentient beings, then we generate bodhicitta because that transforms our way of relating to them. It transforms our attitude, and it restores a good relationship with sentient beings. Then third, we make a determination not to do the action again.

If we can’t really say with total confidence, “I’m never going to gossip again,” then say, “Okay, for the next three days I’m not going to gossip.” And then be really attentive and then try for a fourth day after that and then try for a fifth day. The fourth of the four opponent powers is some kind of remedial action, so this could be reciting mantras, reciting the names of the Buddha, bowing, prostrating, making offerings, meditating on bodhicitta, meditating on emptiness, offering service at a Dharma center or a monastery or making offerings to a charity or doing some social welfare work, doing some volunteer work. This is any kind of virtuous action, like helping to print Dharma books. There are many kinds of virtuous actions, so this is doing something virtuous.

Questions & Answers

Audience: Maybe it’s just more of a technical thing, but on this remedial action, if you’re doing any of the virtuous activity with an open and kind heart, does it have to be intentionally with the motivation of purifying something specific or is it purification kind of just as a result?

VTC: No, we don’t have to think we’re doing this to purify a specific non virtue. It can be helpful sometimes for us if we’ve done something to think, “I really feel bad about that and I want to do something that is completely opposite to that, so tomorrow I’m going to do this virtuous action.” But when you are doing a virtuous action, it will still help you purify even if you’re not thinking it’s particular for a certain negative action.

Audience: How exactly does that work? How does doing a good action take away the negative karma that you have just got done creating?

VTC: How does doing a good action impede the ripening of a negative action that you just created? When you create a negative action you’re leaving like a trace of energy behind, and that energy is going in a certain direction. If you do something virtuous it’s like putting a roadblock so that energy can’t keep going in that direction. So, we’re putting up roadblocks. It’s like if you do one negative action many, many times—even if the action is negative, the force of doing it repeatedly makes it stronger. It’s kind of like you have a little stream but you keep adding more and more water and so it gets to be a big powerful river; but then if you start to do some virtue, you’re putting an impediment so that the energy can’t go in that direction.

Audience: When we die does that mean that our good karma has run out?

VTC: No, because birth is the cause of death. As soon as you’re born, you’re going to die. The karma for this specific lifespan has run out, but that doesn’t mean all of our good karma has run out. It is just whatever karma is ripening in our present life span. Asking the question in that way implies that if you create more and more virtue then you’re never going to die. How is that going to happen? Everybody has to die.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: So, the question is if you don’t have a formal altar—maybe you have a statue of the Buddha and a picture of your teachers—and you don’t offer anything, should you take those things down? What do you think?

Audience: There are things for an individual altar that I don’t have yet because I don’t have water bowls.

VTC: So what? So what? You don’t have your own set of water bowls. Use your own mind—is it better to see a Buddha statue or not see a Buddha statue?

Audience: It’s better, but I didn’t want to be disrespectful.

VTC: Is it more respectful to put a Buddhist statue out there and not make offerings or to put it in a cabinet?

Audience: I’m probably overthinking because I have set up the altar like the scripture [inaudible] and you know, the stupa.

VTC: You think, you think [laughter]—yeah, and you don’t need water bowls. You can take a piece of fruit and offer that. You can have one bowl and offer that. You can not offer anything. It is still wonderful to see religious objects.

Audience: You can bow to it.

VTC: Yeah, you can still bow.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: No, that’s not the issue. That’s not the issue; it is learning to think.

Audience: So, what we are experiencing right now, we have created these causes in a previous life and so—this is more of a comment or a fear statement—Aryadeva’s text tells us that most of the daily work, we’re struggling with just creating negativity and the importance of purification is so enormous, mostly we are engaging in non-virtue.

VTC: When you think that most of the day our attachment and aversion regarding the eight worldly concerns are operating, then you really see how important it is to do purification practice and that’s why we are always recommended to do purification practice every day—to not miss it for one day but to always do purification practice.

Audience: When we do purification practice does it mean the negative karma will not ripen? If you kill someone or do something very serious, how much purification can you really do?

VTC: If you do purification does it mean the negative karma is not going to ripen? The kind of purification we’re doing before we realize emptiness is we are impeding the karma from ripening. So, it means if it ripens in the sense of negative karma, it will be a smaller result than before, or the result won’t last as long, or the result will happen later in the future giving us more time to do more purification. But it’s only by realizing emptiness directly that we actually remove all traces of the karmic seeds from our mind. And then what was the other one?

Audience: If you do something very serious like killing somebody how much purification can you actually do?

VTC: How much purification can you do? You can do as much as possible.

Audience: Does it have an effect?

VTC: Of course—whatever we do has an effect, so even if it’s something very serious, if we practice the four opponent powers we are able to purify. And it definitely has an effect because all functioning things have effects, don’t they? So, don’t just kind of blow it off and say, “Oh, that was so negative, I could never purify.” We’ll never get anywhere if we have that attitude.

Audience: If we have to tell someone that what they do is not correct and they may not be happy, by making them unhappy because of our action out of goodwill, do we still have bad karma?

VTC: Okay, so think about this for yourself. You did something with a good intention. Somebody else gets offended. Is that negative? If they get offended when you had a good intention, is their anger or feeling of offense your responsibility? Did you intend for them to react that way? Think: if you didn’t have that intention and you had a good intention, you cannot control how other people respond. We can never control how other people respond. So, what makes an action virtuous or non-virtuous is not the other person’s response; it is our motivation because sometimes we do things with horrible motivations and other people love us afterward. Does that mean that we did a virtuous action because somebody was happy? No.

Audience: This is a long comment from Jim. He says: “I’ve been thinking about purification. I think about its impact on my mind and how thoughts create neural pathways, so the longer we think in that pattern the stronger that thought pattern becomes physically in the brain. By purifying we are changing our neural pathways making it less likely that we will have that thought that leads to the negative action in the future.”

VTC: So, you’re thinking from a scientific viewpoint that when you do something repeatedly it strengthens the neural pathways and leads to a certain thing. Yes, it does that. But that’s not necessarily how repetition of an action works because when you die, your brain stays here and your neural pathways cease, but your karma goes with you. So, don’t make karma into some material thing, like thinking it’s your neural pathways. Because when you die your brain stops, your neural pathways stop, but your karma goes with. But in a mechanical way, yes, you do strengthen neural pathways that affect this lifetime.

Audience: I’m wondering about the example the person had about the harmful crime and asking if you can purify it—you responded that when we purify and we haven’t realized emptiness, we are doing one level of purification and then when we have emptiness we are taking it from the root. Can you think of this like the purification that we do before we realize emptiness is like the conditions of being affected whereas when you have realized emptiness you’ve kind of gotten to the cause?

VTC: Yes, before we realize emptiness our purification blocks the ripening of that karma or affects how it ripens, so it’s going to affect the conditions that affect how that karma ripens. But it also weakens the potency of that seed as well. It definitely weakens the potency of the karmic seed. But only when we have realized emptiness directly do the seeds start disappearing from the mindstream altogether.

Is there anything else? Okay, then that’s it. I think you have something to think about this week. Maybe do a little bit of thinking about virtuous and non virtuous actions, and try and live according to the guidelines for refuge. If you’re doing Vajrasattva practice or prostrations to the 35 Buddhas, really make sure that your practice of the four opponent powers is nice and clear while you’re doing that.

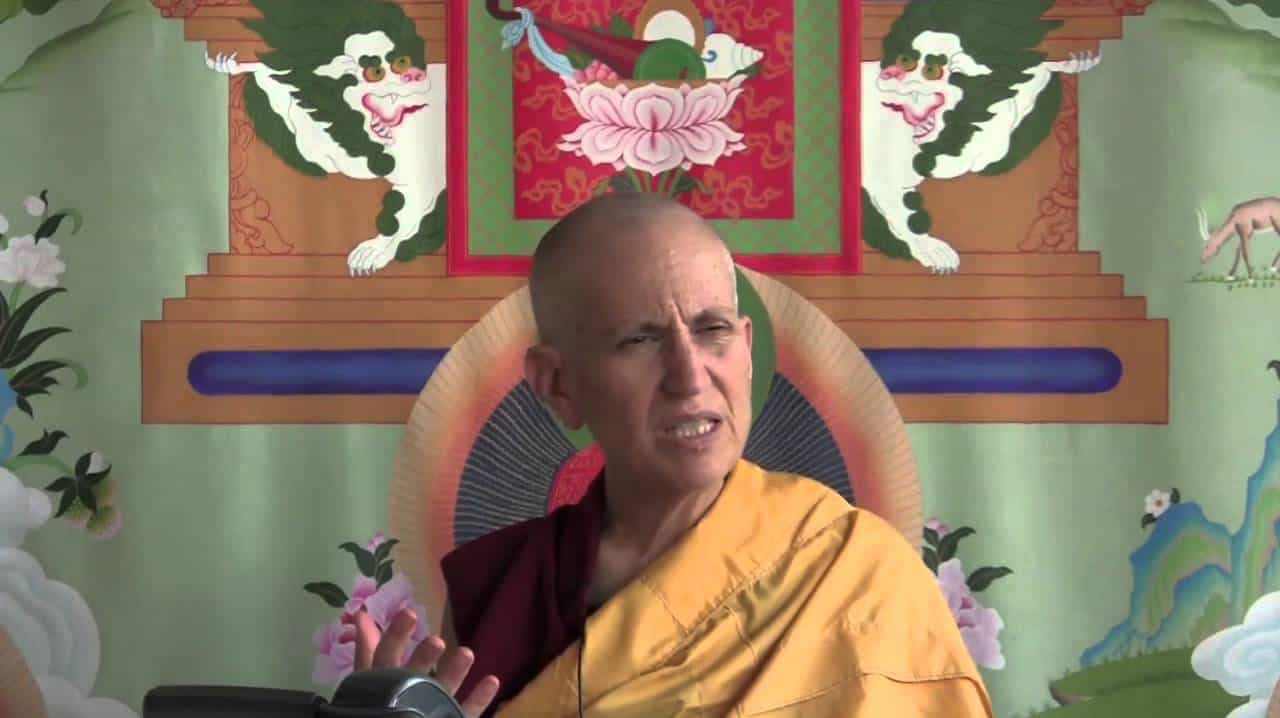

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.