A monastic’s mind

A talk to new sangha

A talk given at Tushita Meditation Centre, Dharamsala, India.

I’m happy to have this time to talk with the sangha. It was nice coming up the hill and seeing so many sangha eating together. Lama Yeshe cared so much for the sangha and would have been happy to see this. When I was ordained in 1977, things were different: the facilities were more primitive and the sangha was not able to eat together at Tushita.

When we choose to ordain, it’s because there’s some spiritual yearning, something very pure inside of us. We should value this quality in ourselves, respect it, and take care of it.

I’ll talk a little bit this afternoon and then leave some time for questions. My hope is that we will discuss some of the things that you cannot discuss with Tibetan teachers. We encounter many cultural differences when we ordain. Sometimes these are not verbalized, and we can’t talk about them. Sometimes we don’t even recognize them ourselves. But they nevertheless affect us. I’m hoping our time together today will provide a forum to discuss some of these points.

The value of ordination and of the precepts

All of you have heard about the benefits of ordination, so I won’t repeat them now. I see these clearly in my own life. Whenever I do the death meditation, and imagine dying, looking back over my life, and evaluating what’s been of benefit in my life, keeping ordination always comes out as the most valuable thing I’ve done. Doing tantric practice, teaching the Dharma, writing books—none of these come out as the most valuable thing in my life. I think keeping ordination comes out so important because it has provided the foundation for me to do everything else. Without ordination, my mind would have been all over the place. But ordination gives us guidelines and direction. It provides a way to train our mind and steer it in a positive direction. On the basis of that we are able to do all other Dharma practices. Ordination gives us useful structure in our lives.

It’s helpful and important for us to think of the value of each of our precepts. Let’s take the precept to avoid killing. What would our lives be like if we didn’t have that precept and could take others’ lives? We could go out to restaurants and eat lobster. We could hunt and use insecticides. Are these activities we want to do? Then think: how has keeping that precept affected my life? How has it improved how I relate to others and how I feel about myself?

Do the same reflection for the precepts to avoid stealing and sexual contact. What would our life be like if we didn’t have those precepts and engaged in those actions? What is our life like because we live in those precepts? Go through each precept and reflect on it in this way.

Sometimes our mind gets restless, thinking, “I wish I didn’t have these precepts. I’d like to go out and find some nice guy and smoke a joint and… ” Then think, “What would my life be like if I did that?” Play out the whole scene in your meditation. You go to McLeod Ganj, have a good time… and?! How would you feel afterwards? Then, when we consider that we didn’t do that, we see the value of the precepts, how precious each precept is because it keeps us from wandering all over doing things that just leave us more dissatisfied.

If we think about each precept in that way, we’ll understand its meaning and purpose. When we understand how it helps us in our practice, the inspiration to live in accord with that precept will come based on our own experience. We’ll know that precepts are not rules telling us what we can’t do. If we see the precepts as rules saying “I can’t do this and I can’t do that,” we’ll probably disrobe after a while because we don’t want to live in prison. But, the precepts are not prison. Our own berserky mind—especially the mind of attachment that wants to go here and there, that wants more and better, grasping everything —is prison. When we see the problems that the mind of attachment causes us, we understand that precepts prevent us from doing what we don’t want to do anyway. We won’t think, “I really want to do all these things and I can’t now because I’m a monastic!” Rather, we’ll feel, “I don’t want to do these things, and the precepts reinforce my determination not to do them.”

If we see our ordination in this way, being ordained will make sense to us and we’ll be glad to be a monastic. Being happy as a monastic is important. Nobody wants to be unhappy, and being a monastic is difficult if we’re miserable. Thus we need to make sure we have a happy mind. To do this, we can ask ourselves, “What is happiness? What creates happiness?” There’s the happiness we get from sense pleasures and the happiness we experience from transforming our minds through practicing Dharma. One part of us thinks that sense pleasures are going to make us happy. We have to really check if this is the case. Or, does chasing after the things of this life—food, sex, approval, reputation, sports, and so on—only make us more dissatisfied?

Ordination isn’t shaving our head and wearing robes, while we continue to act the same way as we did before. The precepts are a support that helps us to keep our practice strong. The external changes in dress and hair remind us of internal changes —the changes in ourselves that got us to the point of wishing to receive ordination and also the changes in ourselves that we aspire to make as ordained people. The more we use our ordination to support our practice and the more committed we are to transforming our minds, the happier we’ll be as monastics.

The rebellious mind

Sometimes, as we practice as a monastic, our mind becomes unhappy or rebellious. It may happen that we want to do something but there’s a precept prohibiting it. There may be some structure or prescribed behavior of the sangha that we don’t like, for example, serving others or following the instructions of those ordained before us. Sometimes we may look up and down the line of sangha, find fault with everyone, and think, “I can’t stand being with these people any more!” When such things happen, when our mind gets in a bad mood and complains constantly, our usual tendency is to blame something outside. “If only these people acted differently! If only these restrictive precepts weren’t there! If only these monastic traditions weren’t the way they are!”

I spent many years doing this, and it was a waste of time. Then something changed, and my practice became interesting because when my mind bumped into external things that I didn’t like, I began to look inward and question, “What’s going on in me? Why is my mind being so reactive? What lies behind all these reactions and negative emotions?”

For example, the sangha has the tradition of sitting in ordination order. Our mind may rail, “The person in front of me is stupid! Why should I sit behind him or her?” We could go on and on complaining about “the system,” but that doesn’t help our bad mood. Instead, we can look inside and ask ourselves, “What’s the button inside me that’s getting pushed? Why am I so resistant to doing things this way?” Then, it becomes clearer, “Oh, I’m suffering from arrogance!” Then, we can apply the antidote to arrogance, for example, by reflecting on the kindness of others. “If I were the best one in the world, if I sat at the head of the row, then it would be a sorry situation because all that people would have to look to for inspiration would be me. Although I have something to offer, I’m certainly not the best. Besides, I don’t want people having grandiose expectations of me. I’m glad some others are better than me, have kept precepts longer, and have more virtue. I can depend on those people for inspiration, guidance, and instruction. I don’t have to be the best. What a relief!” Thinking in this way, we respect those senior to us and rejoice that they are there.

Working with our mind when it is resistant or rebellious makes our practice very interesting and valuable. Practicing Dharma doesn’t mean chanting “La, la, la,” visualizing this deity here and that one there, imagining this absorbing here and that radiating there. We can do lots of that without changing our mind! What is really going to change our mind is lamrim meditation and thought transformation practice. These enable us to effectively and practically deal with the rubbish that comes up in our mind.

Instead of blaming something outside ourselves when we have a problem, we need to recognize the disturbing attitude or negative emotion that is functioning in our mind and making us unhappy, uncooperative, and closed. Then we can apply the antidote to it. This is what practicing Dharma is all about! Keeping our monastic precepts requires a firm foundation in the lamrim. Tantra practice without lamrim and thought transformation is not going to do it.

For this reason, His Holiness the Dalai Lama continuously emphasizes analytical, or checking, meditation. We need to use reasoning to develop our positive emotions and attitudes. During the Mind-Life conference I just attended, he emphasized this again, saying that prayer and aspiration are not enough for deep transformation; reasoning is necessary. Transformation comes from studying the lamrim, thinking about the topics, and doing analytical meditation on them. With a firm grounding in lamrim, we’ll be able to work with our mind no matter what is going on in it or around us. When we do this, our Dharma practice become so tasty! We don’t get bored practicing. It becomes very exciting and fascinating.

Self-acceptance and compassion for ourselves

In the process of working with our mind, it’s important to give ourselves some space and not expect ourselves to be perfect because we’re a monastic. After we ordain, it’s easy to think, “I should act like Rinpoche.” Especially if we have a teacher like Zopa Rinpoche who doesn’t sleep, we compare ourselves to him and think there’s something wrong with us because we have to sleep at night. “I should stop sleeping and practice all night. If I only had more compassion, I could do this.” We become judgmental with ourselves, “Look at how selfish I am. What a disaster I am! I can’t practice! Everybody else practices so well, while I’m such a mess.” We become very self-critical and down on ourselves.

Being like this is a total waste of time. It’s completely unrealistic and has no benefit at all. Nothing positive comes from beating up on ourselves! Absolutely none. I spent a lot of time being very judgmental of myself, thinking that doing this was good and right, and I can tell you from my experience that nothing useful comes from it.

What is a realistic attitude? We have to notice our defects. We notice our weak areas and faults and have some acceptance of ourselves. Accepting ourselves doesn’t mean we’re not going to try to change. We still recognize a certain trait as disadvantageous, a negative quality that we have to work on. But, at the same time, we have some gentleness and compassion for ourselves. “Yes, I have this negative trait. Here it is. It’s not going to disappear completely in the next ten minutes or even in the next year. I’m going to have to work with this for a while. I accept this and know that I can and will do it.”

Thus we have some basic self-acceptance, instead of expecting ourselves to be some kind of perfect human being. When we have that basic self-acceptance, we can start applying the antidotes to our faults and change our life. We have the self-confidence that we can do this. When we lack that self-acceptance and instead beat up on ourselves, saying, “I’m not good because I can’t do this. This person is better than me. I’m such a wreck!” we then push ourselves, thinking, “I’ve got to be a perfect monastic,” and get tight inside. This is not a useful strategy for self-transformation.

Self-acceptance, on the other hand, has a quality I call “transparency.” That is, we’re not afraid of our faults; we can talk about our weak points without feeling ashamed or mortified. Our mind is compassionate with ourselves, “I have this fault. The people around me know I have it. It’s not some big secret!” This transparency enables us to be more open about our faults. We can talk about them without concealing them and without feeling humiliated when we do so. Trying to cover up our faults is useless. When we live with others, we know each other’s faults very well. We have all 84,000 disturbing attitudes and negative emotions. Others know it, so we might as well admit it. It’s no big deal, so we don’t have to pretend that we have only 83,999. In admitting our faults to ourselves and others, we also realize that we’re all in the same boat. We can’t feel sorry for ourselves because we are more deluded than anyone else. We don’t have a greater or lesser number of disturbing attitudes and negative emotions than other sentient beings.

For example, at the Mind-Life Conference last week, I watched my pride come up, followed by anger and jealousy. I had to admit, “I’ve been ordained twenty-three years and I’m still angry, jealous, and proud. Everybody knows it. I’m not going to try to fool anybody and say these emotions aren’t there.” If I recognize them, don’t blame myself for having them, and am not afraid to acknowledge them in front of you, then I’ll able to work with them and gradually let them go. But, if I beat up on myself, saying, “I’m so proud. That’s terrible! How could I be like that?!” then I’ll try to cover up these defects. By doing so, I won’t apply the antidotes to these negative emotions because I’m pretending I don’t have them. Or, I’ll get stuck in my self-judgment and won’t think to apply the antidotes. Sometimes, we think that criticizing and hating ourselves are the antidotes to negative emotions, but they’re not. They just consume our time and make us feel miserable.

One of the values of living with other sangha is that we can be open with each other. We don’t have to pretend that we have everything figured out when we know we don’t. If we’re sentient beings, we don’t have to have it all together! Having faults is nothing surprising, nothing unnatural. As sangha, we can support and encourage each other as we each work with our own problems. I’m telling you this because I spent many years thinking I couldn’t talk with fellow monks and nuns about my problems because then they’d know what a horrible practitioner I was! I think they knew that anyway, but I was trying to pretend that they didn’t. And so, we seldom talked with each other about what was going on inside. That was a loss.

It’s important to talk and be open with each other. For example, we admit, “I’m having an attack of anger,” and avoid blaming another person for being mean. We stop trying to get others to side with us against him. Instead we recognize, “I’m suffering from anger right now” or “I’m suffering from loneliness.” Then we can talk with other sangha. As Dharma friends, they will give us support, encouragement, and advice. This helps us to resolve our problems and progress along the path.

Sometimes when we have a problem, we feel we’re the only one in the world who has that problem. But when we can talk about it with fellow monastics, we recognize that we’re not alone, trapped in our own shell, fighting an internal civil war. Everyone is going through similar stuff. Realizing that enables us to open up with others. They can share how they deal with a similar problem and we can tell them how we work with what they’re going through right now. Thus we support each other, instead of holding things inside, thinking no one will understand.

A monastic’s mind

In a discussion with Amchok Rinpoche several years ago, he said to me, “The most important thing as a monastic is to have a monastic’s mind.” I’ve thought about this over the years and have concluded that when we have a “monastic’s mind,” things will naturally flow. Our whole way of being is as a monastic. We can think about what a “monastic’s mind” means for years. Here are some of my reflections.

One of the first qualities of a monastic’s mind is humility. Humility has to do with transparency, which is related to self-acceptance. With humility, our mind relaxes, “I don’t have to be the best. I don’t have to prove myself. I’m open to learning from others. It makes me feel good to see others’ good qualities.”

Humility can be difficult for us Westerners because we were raised in cultures where humility is seen as weakness. People in the West pull out their business cards, “Here I am. This is what I’ve accomplished. This is what I do. This is how great I am. You should notice me, think I’m wonderful, and respect me.” We were raised to make others notice us and praise us. But this is not a monastic’s mind.

As monastics, our goal is internal transformation. We’re not trying to create a magnificent image that we’re going to sell to everyone. We have to let that seep into our mind and not worry so much about what other people think. Instead, we should be concerned with how our behavior influences other people. Do you see the difference between the two? If I’m worried about what you think of me, that’s the eight worldly concerns. I want to look good so that you’ll say nice things to me and will praise me to others so that I’ll have a good reputation. That’s the eight worldly concerns.

On the other hand, as monastics, we represent the Dharma. Other people will be inspired or discouraged by the way we act. We’re trying to develop bodhicitta, so if we care about others, we don’t want to do things that will make them lose faith in the Dharma. We do this not because we’re trying to create a good image and have a good reputation but because we genuinely care about others. If I hang out in chai shops all day or if I shout from one end of the courtyard to the other, other people will think poorly of the Dharma and the sangha. If I jostle people when I go into teachings or get up in the middle and stomp out, they’re going to think, “I’m new to the Dharma. But I don’t want to become like that!” Thus, in order to prevent this, we become concerned about the way our behavior affects other people because we genuinely care about others, not because we’re attached to our reputation. We must be clear about the difference between the two.

A monastic’s mind has humility. It also is concerned for the Dharma and others’ faith in the Dharma. Generally, when we are first ordained, we don’t feel this concern for the Dharma and for others’ faith. New monastics generally think, “What can the Dharma give to me? Here I am. I’m so confused. What can Buddhism do for me?” Or, we think, “I’m so sincere in wanting to attain enlightenment. I really want to practice. Therefore others should help me to do this.”

As we remain ordained longer and longer, we come to understand how our behavior affects other people, and we begin to feel some responsibility for the continuity of the teachings. These precious teachings, which have helped us so much, began with the Buddha. They were passed down through a lineage of practitioners over the centuries. Because those people practiced well and remained together in communities, we are fortunate enough to sit on the crest of the wave. We feel so much positive energy coming from the past. When we receive ordination, it’s like sitting on the crest of the wave, floating along on the virtue that all the sangha before us have created for over 2,500 years. After some time,we begin to think, “I’ve got to contribute some virtue so that future generations can meet the Dharma and other people around me can benefit.” We begin to feel more responsible for the existence and spread of the teachings.

I’m sharing my experience. I don’t expect you to feel this way now. It took me many years to recognize that I was no longer a child in the Dharma, to feel that I am an adult and so need to be responsible and give to others. Often we come into Dharma circles or into the sangha thinking, “What can I get out of the sangha? How is being with these monks and nuns going to benefit me?” We think, “We’re going to have a monastery? How will it help me?” Hopefully after some time our attitude changes and we begin to say, “What can I give to the community? How can I help the sangha? What can I give to the individuals in the community? What can I give to the lay people?” Our focus begins to change from “What can I get?” to “What can I give?” We talk so much about bodhicitta and being of benefit to everybody, but actually putting this into practice in our daily life takes time.

Slowly, our attitude begins to change. If we look at our ordination as a consumer and think, “What can I get out of this?” we’re going to be unhappy because we’ll never get enough. People will never treat us well enough or give us enough respect. However, we’ll be much more satisfied as monastics if we start to ask ourselves, “What can I give to this 2,500-year-old community? How can I help it and the individuals in it so that they can continue to benefit society in the future? What can I give to the laypeople?” Not only will we feel more content inside ourselves when we change our attitude, but we’ll also be able to make a positive contribution to the welfare of sentient beings.

To make a positive contribution we don’t need to be important or famous. We don’t need to be Mother Theresa or the Dalai Lama. We just do what we do with mindfulness, conscientiousness, and a kind heart. We shouldn’t make a big deal, “I’m a bodhisattva. Here I am. I’m going to serve everybody. Look at me, what a great bodhisattva I am.” That’s trying to create an image. Whereas if we just try to work on our own mind, be kind to other people, support them in their practice, listen to them because we care about them, then slowly a transformation will occur within ourselves. Who we are as a person will change.

Working with down times

We’ll all have problems in the future. If you haven’t before, you will probably go through a time of feeling very lonely. You might go through a time of thinking that maybe you shouldn’t have ordained. You might find yourself saying, “I’m so bored.” Or “I’m so tired of being pure. Anyway my mind is a mess. I should just give up.” Or you might think, “I’d feel so much more secure if I had a job. I’m turning forty and don’t have any savings or health insurance. What’s going to happen to me?” We may feel, “If only someone loved me, I’d feel better. I wish I could meet a significant other.”

Sometimes we may be flooded with doubts. It’s important to recognize that everybody goes through these kinds of doubts. It’s not just us. The lamrim is designed to help us deal with these mental states. When we go through periods of doubt and questioning, it’s very important not to blame our ordination, because our ordination is not the problem.

When we’re lonely we might think, “Oh, if I weren’t ordained I could go down to McLeod and meet a nice person in the restaurant, and then I won’t be lonely.” Is that true? We’ve had plenty of sex before. Did that cure the loneliness? When the mind starts telling the story, “If only I did this, then the loneliness would go away,” we need to check if doing that will really solve the loneliness or not. Often what we do when we’re lonely is like putting a Band-Aid on somebody who has a cold. It’s not going to work. That’s not the right antidote for loneliness.

At those times, we need to work with our mind. “Okay, I’m lonely. What is loneliness? What’s going on?” We feel, “Why doesn’t anybody love me?” I used to remember my teenage years when I constantly wondered and wished, “When is somebody going to love me?” This made me realize that feeling I wanted to be loved was not a new problem, it’s been going on for years. So I had to look at what’s going on in my mind. What’s behind the feeling of “Why doesn’t somebody love me?” What is it that I’m really seeking? What’s going to fill that hole?

We just sit there with these kinds of puzzles and questions. In our mind we keep trying on different solutions to see what will help the loneliness and the wish to be loved. I’ve discovered that the lamrim helps a lot in this regard. It helps me to let go of fantasies and unrealistic projections. In addition, the bodhicitta meditations help me open my heart to others. The more we can see that everyone wants to be happy, the more we can open our hearts to have equal love for others. The meditation on the kindness of others helps us to feel the kindness others show us now and have shown us since we were born. And even before that! When we see that we’ve been the recipient of so much kindness and affection, our own heart opens and loves others. We stop feeling alienated because we realize that we’ve always been connected to others and to kindness. When we experience this, the loneliness goes away.

We need to work with our difficult emotions instead of running away from them, stuffing them down, or acting them out, let’s say by thinking that we’d be happier if we got married and got a job. We just sit and work with our own mind, take refuge and start developing a heart that loves others. The mind inside of us that says, “Why doesn’t somebody love me?” is the self-centered mind, and it’s already made us spend a long time feeling sorry for ourselves. Now we’re going to try opening our hearts to others, extending ourselves to others, and letting a feeling of well-being and connection arise inside of us.

The other day at the conference, His Holiness was talking about the bodhisattvas of the first bhumi, which is called Very Joyful. At this stage they have just realized emptiness directly in the path of seeing. His Holiness said these bodhisattvas have so much more happiness than arhats. Even though arhats have eliminated all the disturbing attitudes and negative emotions that had kept them bound in samsara while the first bhumi bodhisattvas have not, these bodhisattvas are still millions of times happier than the arhats. What gives these bodhisattvas so much joy is the love and compassion they have cultivated in their hearts. For this reason, the first bhumi is called Very Joyful. They are joyful not because of their realization of emptiness—because the arhats have that too—but because of their love and compassion.

He then said, “Although we think that others experience the result of our developing compassion, in fact it helps us more. Our developing compassion is for everybody’s benefit, including our own. When I develop compassion, I benefit 100%. Other people only get 50%.”

It’s true. The more we recognize that we all equally want to be happy and to avoid suffering, the more we feel in tune with others. The more we recognize that we and others equally don’t want to be lonely and want to feel connected, the more our own heart opens to others. When we start opening our heart to other people, then the love we feel for everyone, including ourselves, fills our heart.

Robes

We should be happy to wear our robes and we should wear them everywhere, all the time. The only times I have not worn them was the first time I saw my parents after I ordained —because Lama Yeshe told me to wear lay clothes—and when I went through customs at the Beijing airport. Otherwise, I travel in India, the West, worldwide, in my robes. Sometimes people look at me, and sometimes they don’t. I am completely immune to their looks by now. Years ago in Singapore, I was walking down Orchard Road, and a man looked at me as if he had seen a ghost. I just smiled at him, and he relaxed. When we feel comfortable in our robes, then even if people look at us, we smile at them and they respond with friendliness. If we’re relaxed wearing robes, other people will also be relaxed with it.

It could happen that in the West we will eventually alter the style of the robes to be more practical. This was done in previous centuries in several Buddhist countries. What is important, however, is that we dress like the other sangha of that place. If we wear a sweater, we should wear a maroon sweater, not one that is maroon with a little blue border, or one that is bright red, or one that is fancy. Chinese monastics have jackets, with collars and pockets, that look very tidy. It would be nice if at some point we standardized our jackets and sweaters so we would look alike.

Shoes and backpacks are status symbols among the Tibetan monastics. We should not emulate this. We should dress like everyone else and be simple and practical.

Here in Dharamsala, we look like everyone else. In the West, we don’t look like other people on the street. We have to learn to be content either way, not trying to be different when we’re with sangha in India yet trying to blend in when we’re with laypeople in the West.

Geshe Ngawang Dhargey told us, when we put on my robes each morning, to think, “I am so glad that I am ordained.” He said to treasure the robes and treasure our fortune to be ordained.

Most of you know that we put our shamtab on over our head. Out of respect for our ordination, we don’t step into our shamtab. Fully ordained monastics should always have their three robes with them wherever they sleep at night, even if they are traveling. Getsuls and getsulmas have two robes, the shamtab and chögu. Keep your hair short. If you live in a colder climate, it may grow a tiny bit longer, but avoid having it too long. In the West I wear my zen when I teach or listen to teachings and a jacket or sweater when I go out, because I live in Seattle and it is cold there. I don’t wear my zen when I go out in the street there, because the wind blows it all over. In the summer I wear a maroon Chinese monastic jacket in the street, because I feel more comfortable being covered.

Always wear your zen at teachings. When you put on your chögu or your zen, put it on gracefully. Don’t spread it out and toss it around as you put it on so that it hits the people around you. Unfold it first, then put it around your shoulder in a small circle.

Etiquette

Etiquette and manners in daily interactions are a training in mindfulness. Don’t eat while you walk. Lama was really strict about this; whenever we eat, we are seated. When a monastic munches popcorn or drinks a soft drink while walking down the street, it doesn’t give laypeople a very good impression of the sangha. We may eat in a restaurant from time to time, but we shouldn’t be hanging out in chai shops or restaurants. We didn’t get ordained in order to be the chai shop guru or the chai shop socialite.

To share some practical do’s and don’ts: avoid shouting long distances so that others are disturbed and look at you. Be mindful when you open and close doors. Be aware of how you move your body. We can learn a lot about ourselves by observing how we move. We notice that when we are in a bad mood, we walk differently and send out a different energy to the people around us.

The various guidelines for etiquette and manners aren’t just rules saying, “Don’t do this or that.” They are training us to be aware of what we are saying and doing. This, in turn, helps us to look at our mind and observe why we are saying or doing something.

In Chinese monasteries they are very strict about how we push in our chair, clean our dishes, and so forth. We do these quietly. Don’t expect somebody else to clean up after you. When you see an old friend, greet him or her warmly, but don’t scream with joy and make a lot of noise.

In most Asian countries, avoid all physical contact with the opposite sex. The Tibetan tradition is a bit more relaxed, and we shake hands. But don’t shake hands in a Theravada or Chinese country.

Don’t hug members of the opposite sex, unless they are family members. In the West, it can be embarrassing when people of the opposite sex come up and hug us before we can do anything to stop it. Do your best to reach out your hand to shake theirs first. That shows them that they shouldn’t hug you. We may hug people of the same sex in the West, but we shouldn’t make a big display of it.

Be on time for teachings and pujas. Make that part of your bodhicitta practice. Care about others enough to be in your seat on time so that you don’t have to climb over them or disturb them by arriving late.

Don’t always follow the Tibetan monks or nuns as examples. I came to Dharamsala over twenty years ago and have seen the monastic discipline degenerate a lot since then. Don’t think, “The Tibetan monks run, jump, and do Kung Fu chops, so I can too.” Lama Yeshe used to tell us, “Think about the visualization you’re giving to other people.” What does it look like to lay people when the sangha shouts, runs, or pushes?

Our body language expresses how we feel inside, and it also influences others. How we sit in our own room is one thing. But when we are with lay people in a formal situation, if we sit in the best chair at the head of the table, stretch out on the sofa, or lean back in a big chair and cross our legs, what are we expressing about ourselves? How will that influence them?

In the Chinese monasteries, we were trained not to cross our legs or stand with our hands on our hips. Why? In our culture, such postures often indicate certain internal attitudes. By becoming more mindful of our body language, we become aware of the messages we convey to others on subtle levels. We also become aware of what is going on in our minds.

When I was training in the Chinese monastery, the nuns kept correcting me because I’d have my hands on my hips. I began to realize how I felt inside when I had my hands on my hips. It was very different than when I had my hands together in front of me or at my side. The more we become aware of things like that, the more we learn about what is happening in our mind.

Although we need to be mindful about our body language and behavior, we shouldn’t be uptight about it. We can laugh, we can be happy, we can joke. But we do these mindfully and at appropriate times and in appropriate circumstances.

Daily life

It’s good to do three prostrations in the morning when we first get up, and three prostrations in the evening before going to bed. Some people are morning meditators, some people are evening or afternoon meditators. It’s good to do some practice at least every morning and evening, but depending on the type of person you are—morning meditator or evening meditator—practice more at the time that works best for you. Don’t leave all your practices for the night, because you probably will fall asleep instead. It’s very good to get up early in the morning, set your motivation, and do some of your practices before starting the day’s activities. It helps us to begin the day in a centered way.

In the morning, think, “The most important things I have to do today are to do my practices, keep my precepts, and have a kind heart towards others.” Those are the most important things. It’s not going to the train station; it’s not sending that fax; it’s not organizing this or talking to that person. “The most important thing that I have to do today is to keep my mind centered, balanced, and comfortable.” Then, everything will flow from there. If you live in a Dharma center, make sure that you don’t get so involved in the center’s activities that you start sacrificing your practice.

As new monastics, it’s important to learn the precepts. That doesn’t mean just reading the list. We should request in-depth teachings on the precepts from senior sangha. What is the boundary of remaining a monastic? How do transgressions occur? How do we purify them? How can we prevent them? What is the value of living in the precepts? The Vinaya is rich with interesting stories and information, and studying it helps us.

Questions and answers

I could talk for hours. But let’s have time for your questions now.

Self-esteem and focusing on the long-term goal

Question: After being ordained, I noticed major self-cherishing and eight worldly concerns in my mind. I thought, “I bet everyone in the Dharma center back home is trying to figure out how to keep me from coming home as a nun,” and other things. My self-esteem plummeted right after ordination, and I thought, “I can’t do this. I’m not worthy.”

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Living in ordination is very strong purification, and when we purify, we see our mental garbage. That’s natural! When we clean the room, we see the dirt. We can’t clean the room unless we see the dirt. When this stuff comes up, we see where the dirt is and see what we need to work on.

When such thoughts of low self-esteem come up, ask yourself, “Is that true? Are these stories I’m telling myself about how awful I am actually true?” Our mind thinks all sorts of stuff, and we shouldn’t believe all of it! When our mind says, “I’m not worthy of taking ordination,” we should examine, “What does ‘worthy’ mean? Does ‘worthy’ mean we’re already supposed to be arhats or bodhisattvas before we ordain?” No, it doesn’t. The Buddha said that ordination is a cause of becoming an arhat or a bodhisattva; it’s a cause of enlightenment. We get ordained because we’re imperfect, not because we’re perfect. So the mind that says, “I’m not worthy of this” is false.

When these kinds of thoughts come up, look at them and analyze if they are true or not. “What’s everybody going to think of me back home?” I don’t know. Who cares? I’m not that important that they’re going to spend most of their time thinking about me! Some people will say, “I’m so glad she ordained!” and some people will say, “Why did she do something like that?!” Whatever you do, somebody’s going to like it and somebody’s not going to like it. Let them sort that out.

We’ll go through times when our practice is strong, and we’ll go through times when our mind seems full of self-centeredness. The key to keep on going is to focus on our long-term goal. When we’re headed for enlightenment, our present happiness and unhappiness aren’t such big concerns. We’re content simply to create the causes for goodness.

When we have a long-term goal we know what we’re doing. When our mind fills with doubts—”Oh, I wish this,” or “How come things xyz?”—we come back to what our priorities are in life. Progressing on the path to enlightenment is chief. We remind ourselves, “If I don’t practice the path, what else am I going to do? I’ve done everything else in samsara millions of times. If I don’t try and follow the path to enlightenment, what else is there? I’ve been it all. I’ve done it all. I’ve had everything there is to have in samsara zillions of times in my previous lives. Look where all that’s gotten me? Nowhere!! So even if enlightenment takes 50 zillion eons, still it’s worthwhile because there’s nothing else worthwhile to do. This is what is most meaningful.” If we can think of something else that’s better, let’s do it! But, it’s very difficult to think of something more worthwhile, something that’s going to bring more happiness for ourselves and others than cultivating the path to enlightenment.

When we’re headed towards enlightenment, if we hit a glitch on the path, that’s okay. If we’re going towards Delhi and we hit a bump in the road, we continue on. So, don’t worry about bumps in the road.

When we hit a bump, it’s important to recognize the role our mind is playing in making that obstacle. Many people hit a bump in the road and think, “I’m having problems because of the ordination. If I weren’t ordained I wouldn’t have this problem.” If we look closer, we’ll see our ordination is not the problem. The problem is our mind. So, if I’m going toward enlightenment and my mind is creating a problem, then I work with my mind because doing that is valuable. It may be uncomfortable and sometimes I may be unhappy, but if I were a lay person, I’d still be uncomfortable and unhappy, only much more.

Relating to old friends

Question: How do we relate to old friends? I’ve been ordained for about fifteen months and recently went back to the West for a visit. I was unsure how to relate to my old friends while living as a monastic amongst them. How much should I see them and when should I excuse myself from their activities because I’m now a nun?

VTC: Often when we meet old friends, we don’t feel the way we used to. We all change, and it’s okay. We don’t have to fit in the way we used to. Sometimes we may think, “But they are my old friends. I love them so much, but I can’t be as close to them now, because I can’t eat at night or hang out at the bar.” They want to take us to the movies, but we don’t go to entertainment, so we feel, “I don’t fit in with these people. What’s wrong? Should I change and be theway I used to be?”

At the beginning this creates some anxiety, but the more we find our own stability, integrity, and dignity as monastics, this doesn’t bother us as much. “Dignity as a monastic” doesn’t mean arrogance. Rather, it’s a sense of what we are doing in life. We are confident, “This is what I do in life. When what my old friends do and what I do correspond, that’s nice. But when they don’t, that’s okay. They can do what they do and I’ll do what I do.”

It’s okay if you and your old friends have different interests and your relationships go in different directions. I ordained in India and lived here for some years. When I went back to the West to visit, some of my old friends were surprised I was a nun, and some weren’t. I still see some of them from time to time in the West, but I’ve lost touch with most of them. That’s okay. Relationships change all the time. Whether we’re ordained or not, we’ll drift away from some friends because our lives and interests go in different directions. With other friends, despite the difference in lifestyles, the friendships will continue and we will communicate very well. When we have a sense of well-being inside ourselves and a sense of what we are doing with our life, we’ll accept it when some friends go different directions as well as when other friendships continue.

Let things be as they are. It will take your old friends a while to get used to you being a monastic, to understand what you will do and what you won’t do, but that’s okay. They will adjust. Some of them will like it, and some of them won’t, and that’s okay. Sometimes we find that what they do and talk about is boring. So much talk about politics, shopping, sports, and what other people are doing. It’s so boring! In that case, we don’t need to keep hanging out with those people. See them briefly, share what you’re able to, and then politely excuse yourself and go do something else.

Wishing for security and cultivating renunciation

Question: What about our financial situation? Should we worry about it or not? Should we get a job?

VTC: I have quite strong views about this. When I first ordained, I made a determination that I was not going to put on lay clothes and get a job, no matter how poor I might be. The Buddha said that if we are sincere in our practice, we will never go hungry, and I thought, “I believe that.” For many years I was very poor. I even had to ration my toilet paper, that’s how poor I was! I couldn’t afford to heat my room in the monastery in France in the winter. But since I ordained in 1977 until now, I’ve never gotten a job and I’m happy about that.

I believed what the Buddha said and it worked. Still, it could be good to have some kind of financial set-up before you ordain. If you feel comfortable thinking as I do, do that. If you don’t, then work longer before you ordain.

Make sure that you feel really comfortable inside with being poor. If you don’t feel comfortable with feeling poor, then don’t ordain yet, because chances are you will disrobe later. I don’t think it is wise to ordain, and then go back to the West, put on lay clothes, grow your hair and get a job, especially if you are living alone as a monastic in a city. Most ordained people don’t make it if they do that because they don’t have the joys of ordained life. They don’t have time to meditate and study. They’re living with lay people, not with a sangha community. They also don’t have the “pleasures” of lay life, because they can’t go out drinking and drugging after work. They can’t have a boyfriend or girlfriend. Eventually people feel like they don’t know who they are any more, “Am I a monastic or a layperson?” They get fed up and disrobe. This is sad. Rather than get yourself into this situation, I think it’s better to wait to ordain until you’ve saved enough money or until you’re able to live in a monastic community.

The Buddha said that we should stay in a sangha community and train with a senior monk or nun for at least the first five years after ordination. We need to build up our internal strength before going into situations that can trigger our attachment. We may feel very strong here in India, but if we go back to the West and dress like a layperson, pretty soon we’ll be acting like one too, simply because the old habits are so strong.

Once we’re ordained, we have to work with the mind that desires comfort and pleasure. I am not saying that we should go on an ascetic trip. That’s silly. But we don’t need to have the best this and the most comfortable that. It is extremely important that, as monastics, we live simply, whether we have a lot of savings or a benefactor or not. To keep our life simple, I recommend giving away something if you have gone a year without using it. If four seasons have passed and we haven’t used something, then it’s time to give it away. This helps us to live simply and enables those who can use the things to have them.

We should not have lots of robes. Actually, in Vinaya, it says that we should have one set of robes. We may have another set to wear when we wash the first, but we consider the second set not ours, but as ones we’ll give to somebody else. We don’t need more than two sets. We don’t need a car, even in the West. We don’t need super comfortable furniture or a kitchen packed with goodies. We should just live simply and be content. With this mental state, we won’t need much money. But, if we like lots of good food, if we want to go to the movies, buy magazines, and have several warm jackets for the winter, then we’ll need a lot of money. But we’ll also run into difficulties keeping our precepts.

We also don’t want to put ourselves into a position where we become a burden on others and they resent having to take care of us. We need to have some money, but we don’t need extravagance. We should wear our robes until they have holes in them; we don’t need to get a new set of robes every year or even every two years. We don’t need to have the latest sleeping bag or the best computer. We need to learn to be content with what we have. If we have internal contentment, then no matter how much we have or don’t have, we’ll be satisfied. If we lack contentment, we may be very wealthy, but in our hearts we will feel poor.

We need to think about organizing ourselves and having monastic communities so we can live together without anyone having to work outside the monastery. Living in a community, we support each other in keeping our precepts and in practicing. The problem is that we Westerners tend to be individualistic, and that makes it hard for us to live in community. We like to do our own trip. We ask, “What will the community do for me?” We don’t want to follow rules. We want to have our own car and don’t want to share things with others. We don’t like having to follow a schedule or work for the benefit of the community. We’d rather go to our own room and meditate on compassion for all sentient beings!

But then, when we’re on our own, we feel sorry for ourselves, “Poor me. There’s no monastery for me to live in. Why doesn’t someone else make a monastery? Then I’ll go there to live.”

We have to look inside ourselves. If we don’t want to go through the difficulties of living in a community, we should not complain about not having the benefits of living in one. If we see the value of setting up a community—for ourselves and others, for the short-term welfare of monastics and for the long-term flourishing of the Dharma—then if we have to sacrifice something, we’ll be happy to do that. Check in your own mind what you want to do. The Buddha set up the sangha as a community so we could support each other in practice. It’s best if we can do that. But we have to make our minds happy to live in community.

Relaxing into structure

Question: Sometimes the structure when we live together makes people tense. How can we be relaxed, warm, and support each other?

VTC: We go through a transition when we learn to live as a sangha community. At first, some things seem strange and other things push our buttons. We have to pause, look at our reactions, and use these situations to learn about our mind.

For example, I’ve observed that newly ordained people love to sit in front. At public teachings, they put their seat even in front of the senior sangha. They think, “Now I am ordained, so I get to sit in front.” But we sit in ordination order, so the new sangha should sit in the back. Often we don’t like that.

Or, the sangha has lunch at 11:30, but we don’t want to eat that early. We want to eat at noon. Or, the sangha eats in silence, but we want to talk. Or, the other sangha are talking, but we want to eat in silence. Or, they said the dedication prayers at the end of the meal, but we haven’t finished (That’s what happened to me today!). Our mind gets tense about all of this. Sometimes we rebel against the structure, sometimes we squeeze ourselves to fit in with it. Neither mental state is very healthy. So rather than try to figure out what to DO, we need to pause, look at our mind, and let ourselves relax.

Structure helps us to stop wasting time thinking about many things. When we sit in ordination order, we don’t have to think about where to sit. We don’t have to worry if there is a place for us. A place will be there. We know where we sit, and we sit there.

In all cultures, eating together is a sign of friendship. Sometimes the sangha can eat in silence, and we can be happy and relaxed when we do that. Other times, when we talk, we can be happy and relaxed and chat together. Try to go with what is happening, instead of having so many opinions about how you would like things to be, or what you think is the best way of doing them. Otherwise, our mind will always find something to complain about. We will spend a lot of time building up our opinions, which, of course, are always right by virtue of their being ours! Structure enables us to let go of all this. We don’t have to think about everything. We know how things are done and we do them like that.

Then, within that structure, we find so much space for our mind to relax, because we don’t need to worry about what to do, where to sit, or when to eat. We usually think the lack of structure gives us space, but without structure, we often have confusion and indecision. Our mind forms lots of opinions, “How come we are having dal-bhat for lunch, I am tired of dal-bhat. Why can’t the kitchen make something else?” Given a choice, our mind will be dissatisfied and complain. But if we get used to eating whatever we’re given, then we’ll be happy.

Of course, the structure should not be so tight that we can’t breathe. But my experience with Western sangha in the Tibetan tradition is that too much structure isn’t our problem.

We get to know the people on either side of us very well when we sit in ordination order. One time I remember thinking, “I don’t like the person on my right because she is so angry. I don’t like the person on my left because she has such a stubborn personality.” I had to stop and say to myself, “I will be sitting by these people for a long time. Whenever I attend a Dharma gathering, I’ll be sitting between this one and that one, so I’d better get used to it and learn how to like them.”

I knew that I had to change, because that is the reality of the situation. I couldn’t say, “I don’t want to sit here. I want to go and sit near my friend.” I had to change my mind, appreciate them, and learn to like them. As soon as I started working on myself, the relationships with them changed. As the years go by, we develop a special relationship with the people we sit near, because we see each other grow and change.

When I got ordained, the Western sangha was basically a group of hippie travelers (some having previously had a career, some not). Do you have any idea what we were like? Now I look at the same people, and see individuals with incredible qualities. I have really seen them grow. It’s heartening to see people work with their stuff and transform themselves, to see their strong determination, and to see the service they offer to others. It’s important that we appreciate each other. Now when I look up and down the line, I see people with many good qualities and rejoice. This one is a translator; that one does a lot to help nuns; this one paints, that one teaches.

Gender issues

Question: Since I have taken ordination in the Tibetan tradition, I feel that I am not just a monastic. There is also an issue about being a woman. We become monastics, but as nuns we are not equal any more. We become inferior to men and monks.

VTC: Yes, I feel this as well. To my mind, this situation is not healthy for the Buddhist community as a whole or for the individuals in it. I lived in the Tibetan community for many years and didn’t realize until I went back to the West, how much the view of women in the Tibetan Buddhist community had influenced me without my knowing it. It had made me lose confidence in myself.

I felt so different in the West. Nobody would look at me strangely if, as a woman, I was in a leadership role or asked questions or voiced my thoughts in a debate. For me, returning to the West was healthy. It was good for me to be in a more open society. There is space there to use my talents.

The situation of women in the Tibetan community has changed in the last twenty years. I believe much of this is due to Western influence and to Westerners asking questions, such as, “Buddhism says all sentient beings are equal. Why don’t we see women doing xyz?”

As Buddhism goes to the West, it is essential that things are gender equal or gender neutral. I am shocked that in some of the prayers used by the FPMT, it still says “The Buddhas and their sons.” Gender-biased language like this was deemed unsatisfactory twenty years ago in the West. Why are Buddhists, and especially Western Buddhists who are aware of gender discrimination, still using it? There is no reason we should use gender-biased language. That needs to change.

In addition, monks and nuns need to be treated equally and to have mutual respect for each other. If we want Westerners to respect the Dharma and the sangha, we have to respect each other and to treat each other equally. I’ve seen some monks behave as if they were thinking, ” Now I am a monk. I’m better than the nuns. I can sit in front of them at teachings. I can tell them what to do.” This is harmful for the monks’ practice, because they develop pride, and pride is an affliction that prevents enlightenment. Having gender equality is good not just for the nuns, but also for the monks.

Question: I noticed when interacting with Western monks that many of them have an attitude, “Oh, you are just a nun.” I was utterly shocked as well as disappointed in them. I don’t buy into their attitude.

VTC: You should not buy into it, and neither should they! Interestingly, I’ve noticed that almost every Western monk who had the attitude, “I am a monk; I am superior to nuns,” has subsequently disrobed. All the ones who put me down and said, “In the lamrim one of the eight qualities of a good human rebirth is being a male,” are no longer monks. The ones who were arrogant and sat in front and made deprecating remarks about nuns have all disrobed. It’s clear that kind of attitude did not benefit them. It was an obstacle in their own path, and it also makes Westerners lose faith in the Dharma. When monks go on that kind of trip, know that it is their own trip. It has nothing to do with you. Don’t lose your self-confidence and don’t get mad at them. If you can point it out in an appropriate way, do that.

Being a raging feminist in the Tibetan community doesn’t work. The monks will completely discredit you. Be respectful. But that does not mean that you lose your self-confidence or suppress your talents and good qualities.

Don’t become obsessed with the gender inequality. I had an interesting experience that helped me to see my own attitudes. Whenever tsog is offered at the main temple, monks offer the large plate of tsog to His Holiness, and monks pass out the offerings. Many years ago, when I was there, I thought, “It’s always the monks who offer to His Holiness. It’s always the monks who pass out the offerings. The nuns have to just sit here and watch.” Then I realized that if the nuns were offering tsog to His Holiness and passing the tsog out to everyone, I would say, “Look, the monks just sit there, and we nuns have to do all the work!” When I saw how my mind thought, I just let go.

We did not become monastics for status, so pointing out gender inequality is not an effort to gain status or prestige. It’s simply to enable everyone to have equal access to the Dharma and to enjoy equal self-confidence when they practice it. It’s good for all of you—monks and nuns—to be aware of this. It’s good that we can talk about it openly. People go on all sorts of trips, and we have to learn to discriminate what is our responsibility and what is coming from the other person. If we see that it comes from another’s arrogance or dissatisfaction, recognize that it’s their trip. It doesn’t have to do with us. But if we provoked or antagonized someone, we have to own up to it and correct ourselves.

We don’t need to become Tibetans

Question: When you just ordained, did you feel pressure to become Tibetan?

VTC: Yes, I did, There were not many Western monks or nuns when I ordained, so I used the Tibetan nuns as role models. I tried very hard to be like the Tibetan nuns. I tried to be extremely self-effacing, speak softly, and say very little. But it didn’t work. It didn’t work because I was not a Tibetan nun; I was a Westerner. I had a college education and a career. It wasn’t appropriate for me to pretend to be this little mouse in the corner who never talked. The Tibetan nuns now, over twenty years later, are a bit more forthcoming, but they are still quite shy.

I tried to adopt Tibetan manners, for example covering my head with my zen when I blew my nose. But I had allergies, which meant that I would spend a great deal of time with my head under my zen. It didn’t work for me to copy Tibetan manners. Now Tibetans realize that Westerners blow their nose without hiding it.

We are Westerners and that’s fine. Working cross-culturally, like we’re doing, makes us look at things we would not normally be aware of if we were only with people from our own culture. We have lots of cultural assumptions that we don’t recognize until we live in a culture that does not have those assumptions. The dissonance makes us question things. We become aware of our internal rules and assumption. This is advantageous, for it makes us ask, “What is Dharma and what is culture?” Sometimes, when our teacher does something that we don’t think is right, we can see it’s because we have different cultural customs or values. It’s not because our teacher is wrong or stupid.

We don’t need to change and try to act or think like Tibetans. It’s fine for us to be Western. His Holiness says, “Even if you Westerners try to be like Tibetans, you still have a big nose.” We don’t need to become Tibetan, but we should tame our minds. We also should be courteous when we are living in another culture.

Responding to criticism

Question: How do you react when lay people tell you that you are not keeping your vows purely?

VTC: If what they say is correct, I say, “Thank you very much for pointing that out to me.” If what the other person says is right, we should thank them. If what they say is not correct, then we explain what is correct. If they tell us to do something against our precepts, we don’t do it. But if they remind us of how to act, we say, “I was not being very mindful. Thank you for pointing that out to me.” Whether they do it with a good or a bad motivation is of no concern to us.

We should help each other on the path. In the Vinaya, the Buddha emphasized this a lot, and, in fact, this is one reason why he had monastics live together in communities. Community life is important because in it, we support each other as well as correct each other when we make mistakes.

Our Western ego finds it difficult to be humble and accept others pointing out our faults. We often lack humility, the first quality of a monastic’s mind, and are proud instead. We have the attitude, “Don’t tell me I made a mistake! Don’t tell me to correct my behavior!”

Yet, to be a successful practitioner, we have to make ourselves into a person who values being corrected. We have to learn to accept people’s suggestions. Whether others give advice in the form of a suggestion or a criticism, for our own good we need to be able to listen and take it to heart. Aren’t we practicing Dharma because we want to change our mind? Did we ordain so we could remain the same, stuck in our old ways? No, of course not. We did this because we sincerely want to improve. So if somebody points out to us that we were being careless or harmful, we should say, “Thank you.” If they tell us that we weren’t acting according to our vows, we should think about what they are saying and see if it’s true.

Question: But what if they say it right in your face, publicly?

VTC: Where are we going to go in the world where nobody will criticize us? Let’s say we’re in a room and we only let people who are nice to us in that room. First we start off with all sentient beings. Then we throw this one out because he criticized us, then that one because she thinks we’re wrong, then this one because he doesn’t appreciate us, and pretty soon we are the only one in the room. We have thrown out all sentient beings, because none of them treated us right. Then will we be happy? Hardly. We have to have tolerance and patience.

When people announce our faults publicly and we feel humiliated, we should make a determination never to do the same to anyone else. We must behave skillfully, and if we have to correct somebody, we should try not do it publicly. Nor should we do it privately in an aggressive or hard-hearted way.

Respecting Western sangha

Question: Could you say something about the fact that some Westerners value Tibetan monastics and teachers more than Western ones?

VTC: Unfortunately, this happens. Usually racism in the West is against Asians, but in the spiritual area, it is different and they are more highly respected. So Western sangha and Dharma teachers experience the result of racial prejudice.

It’s incredibly important for Western sangha to respect other Western sangha. If we ourselves have the attitude, “I’m only going to the teachings of Tibetans because they’re the real practitioners,” or “I’m only going to listen to the advice of Tibetan teachers because Westerners don’t know much,” then we aren’t respecting our own culture and won’t be able to respect ourselves. If we don’t respect other Western sangha, we won’t feel worthy of respect ourselves.

I meet some people who think, “I will only listen to what my teacher says. He is a Tibetan geshe or a Tibetan rinpoche. I am not going to listen to elder sangha, especially Westerners, because they are just like me, they grew up with Mickey Mouse. What do they know? I want the real thing, and that’s only going to come from a Tibetan.”

If we think like that, it will be hard to respect ourselves, because we will never be Tibetans. We are Westerners this whole life. If we think like that, we will miss out on a lot of opportunities to learn. Why? We don’t live with our teachers, so our teachers do not see us all the time. Our teachers usually see us when we are on good behavior. Our teachers sit on the throne; we come in. We are dressed properly, we bow, and we sit down and listen to teachings. Or, we go for an interview with our teacher and sit at his or her feet. We are on our best behavior at those times. We are sweet, helpful, and courteous. Our teacher doesn’t see us when we are in a bad mood, when we’re bossy, when we’re sulking because we were offended, or when we’re speaking harshly to others. Our teacher won’t to be able to correct us at these times because he or she doesn’t see them.

But, the sangha that we live with sees all this. They see us when we’re kind and also when we’re crabby, when we’re gracious and when we’re grouchy. This is why living in a community is valuable. The elder sangha are supposed to take care of the juniors. The elders point those things out to us. It is their responsibility to correct the juniors with kindness.

This kind of learning is invaluable. Don’t think that learning the Dharma just means listening to teachings. It also involves letting ourselves be corrected and learning from the mistakes we make in daily life encounters. It means learning to support and help other sangha members with compassion.

Question: I was thinking more about how the lay community sees Western monastics.

VTC: They follow what they see us do. That’s why I first talked about us respecting other Western sangha. If we show respect to older Western sangha, the lay people will look at us and follow our example. If we only respect the Tibetan sangha, geshes, and rinpoches and treat Western sangha and teachers poorly, Western lay people will do exactly the same. So if we want to change the situation, we have to begin with our own attitude and behavior towards Western sangha.

Initially, I received very little support from Westerners. I think part of it was because I had a racist attitude thinking only Tibetans were good practitioners. I’ve since learned that’s not true. Some Westerners are very sincere and dedicated practitioners and some Tibetans aren’t. We have to look at each individual.

As we practice, we develop some qualities that people see. Then they are more willing to support us. Supporting Western sangha is a topic that Western laypeople need to be educated about. This is one reason why having monasteries in the West is important. When people support a community, the money goes to benefit everybody in the community—seniors, people with qualities, and new people who haven’t developed lots of qualities but who have strong aspiration. The support will be shared equally. If support goes only to those who have practiced for a while, then how will the newly ordained live? If support only goes to teachers, what do people do at the beginning when they don’t have the ability to teach? What happens to the people who don’t want to teach but have many other talents to offer?

In addition, it’s good if we sangha share amongst ourselves. I don’t believe it’s healthy for everyone to have to support themselves. Then we get classes of sangha—those who are rich and those who are poor. The rich ones can travel here and there for teachings. They don’t have to work in Dharma centers because they can support themselves. The poor ones can’t go for teachings and retreat because they have to work in a Dharma center just to get food. That is not right.

This needs education in the lay community and in the sangha community. The main thing is that the more subdued we become, the more laypeople will value what we do and the more they will like having us around. But if we act like them—going to movies, going shopping for this and that, listening to music —then they rightly say, “Why should I support that person? He is just like everybody else.”

Question: In Holland they tell us to be “good” so that people value and support us. But I am very new, and that obligation puts a lot of pressure on me. How do I come to some balance?

VTC: It’s no fun being uptight, is it? If we are happy and relaxed inside, then naturally our actions will be more pleasant. If, through our practice, we are able to work with our garbage, we are more centered. We don’t have to try so hard to be “good.” We don’t have to squeeze ourselves into what we think others think we should be. Just be sincere, do your best, admit when you make a mistake, and learn from it.

Many of our precepts regard what we say and do, because it is easier to control our body and speech than to control our mind. Sometimes our mind is not at all subdued. It’s boiling because we’re furious with somebody. But in those situations, we remember our precepts, and think, “I might be angry inside, but I can’t just blurt everything out. That’s not productive. It doesn’t help me, the other person, or the community. I have to find ways to calm myself, and then go to that person and discuss the issue with him.” At the beginning of our practice, we aren’t very subdued, but if we practice lamrim and thought transformation, gradually our emotions, thoughts, words, and deeds will change. Then people around us will think, “Wow! Look how much this person has changed. She acts so much more subdued than before. She’s so much kinder. The Dharma really works!”

I don’t believe that, generally, people in Dharma centers think that the sangha has to be perfect. We do our best. Sometimes we have to explain, “I’m a beginner. I slip up, but I am trying.”

It’s helpful to look inside and see which of the three poisons is the big one for us. Is it ignorance, anger, or attachment? Whichever is your big one, work principally with that.

For me it was anger. I wasn’t necessarily a person who yelled and screamed. But I had a lot of anger inside, and it came out in all sorts of other ways. Just because we don’t blow up, it does not mean that we don’t have a problem with anger. Sometimes we get so angry that we don’t talk to anybody. We go in our room and won’t communicate. We leave the center or the monastery.

Work with whichever negative emotion is the chief one that afflicts you. Apply the antidotes to it the best you can. Also, be aware of what you say and do, so that even if you can’t control your mind, at least you try not to disturb others too much. If we do lose it and spew our garbage all over others, we should apologize afterwards. When we have the confidence to apologize, we have gotten somewhere in our practice.

Thank you all very much. You are incredibly fortunate to have received ordination, so really treasure it and be happy monks and nuns.

Let’s sit quietly for a couple of minutes. Think about what we have discussed. Then let’s dedicate.

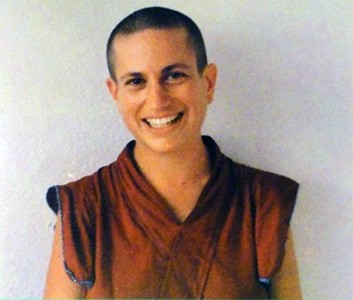

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.