Healing after suicide

A group discussion with parents who had lost their adult children to suicide. (This article is to be included in the forthcoming publication The Suicide Funeral (or Memorial Service): Honoring their Memory, Comforting their Survivors, edited by James T. Clemons, PhD, Melinda Moore, PhD, and Rabbi Daniel A. Roberts.)

“My son, John, whom I loved dearly, shot himself on March 23, five years ago, when he was 27 years old.” “On May 4, 2001, my treasured daughter, Susan, died. She hung herself.” Around the room we went, introducing ourselves, each parent saying their own name and introducing their child who died. I was in a break-out group for parents who had lost their adult children to suicide at the 18th Annual Healing after Suicide Conference in Seattle in April, 2006, which was organized by SPAN (Suicide Prevention Action Network)1 and AAS (American Association of Suicidology). The pain in the room was palpable, but there was also a feeling of close community. Finally, people who had experienced a pain that is rarely spoken of in society—the pain of losing a loved one to suicide—could talk freely to other survivors of suicide who understood what they were going through.

I’d been asked to give the luncheon address as well as to participate in a panel entitled “Suicide: The Challenge to a Survivor’s Faith and Spirituality, and Faith Community Response” at this conference. It was a good thing that my meditation practice had accustomed me to accepting pain, for there was plenty of it here. But there were also warmth and love that are not found at national conferences on other issues. People reached out to strangers because their experiences were not strange.

In the hotel foyer were quilts on the wall, each panel with the face of someone’s loved one who had died by suicide. I looked at the faces—young, old, middle-aged, black, white, Asian. Each of these people had a story, and each left a story of love and of grief behind that their loved ones struggled to understand and accept.

To prepare to speak at this conference, I’d asked the participants of a retreat I was leading, “Who has lost a dear one to suicide?” I was amazed how many hands went up. In reading up on the topic, I was startled to learn that older, white men had the highest suicide rate of all groups. Among teenagers who try to kill themselves, more are girls. However, boys are more successful in completing it. Certainly we need more discussion in the media and public forums about how to prevent suicide and how to diagnose and treat depression. Also, we need to discuss what happens to the family and friends of those who choose to end their lives. What are the survivors’ needs and experiences?

Several survivors at the conference said that they were stigmatized by their friends or communities because of a suicide occurring in their family. I guess I’m naive; I’d never thought that others would close their hearts to friends who were grieving a suicide. I wonder if it was a case of closed hearts or one of people’s own discomfort about death. Or perhaps they wanted to help but didn’t know how?

Some people spoke of friends who “said the wrong thing” that was not helpful to their grieving process. “Uh oh,” I thought, “what if I unintentionally do this during my lunchtime talk?” But my fear subsided in the wake of their openness about their feelings. “If I don’t ‘try to help,’ but am just myself,” I thought, “it’ll be okay.” Just one human being to another.

After the talk, several people came up to thank me for the “breath of fresh air” that talking about compassion brought. I left the conference with great gratitude for all that these courageous survivors had given me by being so open, transparent, and supportive of each other. I especially admire all those in SPAN and AAS who are survivors of suicide and who have transformed their grief into beneficial action for others. My appreciation has grown for the need to expand diagnosis and treatment of depression and bipolar disorder, to educate the public about the importance of suicide prevention, and to care for those who are grieving the loss of a dear one.

The comment of one father touched me deeply. “When death comes,” he said, “make sure you’re really alive.” May we not drown in our complacency or live on automatic. May we cherish our lives and cherish the people around us.

Listen to the audio file of Venerable Thubten Chodron’s talk on the loss of a loved one to suicide given at the 18th Annual Healing after Suicide Conference in Seattle, Washington on April 29, 2006.

For additional information about suicide prevention, visit the websites of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and American Association for Suicidology.

Now known as the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention or ASFP/SPAN USA. ↩

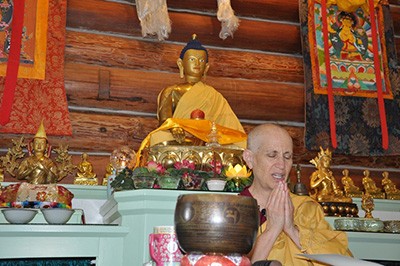

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.