Letting go of self

A Crown Ornament for the Wise, a hymn to Tara composed by the First Dalai Lama, requests protection from the eight dangers. These talks were given after the White Tara Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2011.

- Being in samsara is the root of our problems

- Anger and attachment are not hard-wired into us

- Reification of the self is why we’re attracted to sex and violence

The Eight Dangers 13: The chain of miserliness, part 2 (download)

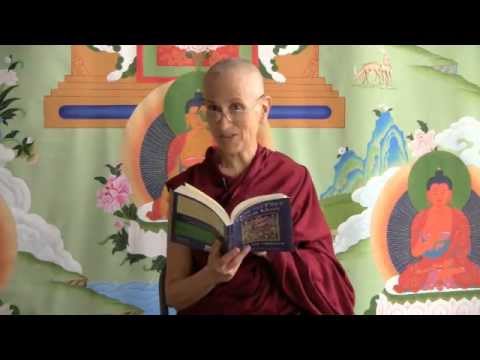

We were talking about miserliness. This is my book. You can’t have it. [laughter]

Binding embodied beings in the unbearable prison

Of cyclic existence with no freedom,

It locks them in craving’s tight embrace:

The chain of miserliness—please protect us from this danger!

“Binding embodied beings in the unbearable prison of cyclic existence with no freedom.” I talked about that last time, and how important it is to keep that in our minds as the basis for our Dharma practice so we don’t get sidetracked by little problems here and now: not getting what we want, or somebody criticizing us, or things not happening the way we want them to happen… We get so sidetracked by those things—caught up in them, agitated by them—but actually they’re not our problem. Our big problem is being in samsara. So that’s what we should pay attention to. Then the little problems, you know, they’re not so big.

This is also asking us, well, what’s at the root of our cyclic existence? And from a Buddhist perspective it’s ignorance.

Now, Saturday when I was at this conference on “hate” sponsored by the Institute for Hate Studies at Gonzaga [University], in one of our discussion groups we were talking and—actually it was the dean of the Gonzaga law school, because we were talking about how people are so attracted towards films with sex and violence…. So the dean said, “Why are we so attracted to this kind of stuff? Why do we just go to it?” And one of the freshmen who was there from Denver University said, “Yes, those are the kind of video games, those are the kind of movies me and my friends want to see. We like them.” So why? Then one person who was a psychologist said, “Well, it’s hard-wired into us.” Attachment and violence are hard-wired into us. And, personally speaking, I find that rather shallow. What does it mean that it’s hard-wired into us? Does it mean it’s controlled by our genes? Controlled by the chemical processes in our brain?

Chemical processes and genes—of course, I say there’s a relationship between our mind and these things—but is it a causal relationship? Because those things are in nature matter, or material. This book is matter and material. So are these glasses. And they’re all made up of atoms and molecules. So you’re telling me that a bunch of atoms and molecules are making me attracted to violence and sex? That atoms and molecules control what I’m attracted to? That doesn’t make sense to me. That just doesn’t. To say that our brain and our genes are the root, and this stuff is hard-wired in—that that’s the root of samsara? I can’t buy that.

From a Buddhist viewpoint, when you analyze and you look at attachment and aversion—our attraction to sex and our attraction to violence—why? It’s because of our grasping at self. We create a self that is reified, we think there’s a real ME here, and then that real ME needs pleasure—it’s attracted to real pleasure; and it feels threatened, so it has to [makes pushing away gesture], stand off against something else. So you get attachment and violence. But what I think is when we get into the films of sex and violence, or discussions about them, why are we so attracted to that? Because those topics make us feel like we exist. Because attachment and hatred—or anger—are very strong emotions. The attachment comes with the sex. The anger comes with the violence. What are those emotions based on? They’re based on this wrong view of the self. What do these emotions increase and substantiate? This view that there’s a real ME. Because without this view of a real ME, we’re not going to be attracted to sex. Without this view of a real ME, we’re not going to be attracted to violence. What is it that makes these things appealing is because we get a big rush, and feel that we REALLY exist, when these emotions are in our minds. So even though the emotions are unpleasant and uncomfortable, or even if they temporarily bring some pleasure, they make us feel that there’s this real “I.” And that’s what we’re addicted to, is this feeling of real “I.”

We’ve talked before about how sometimes people can’t stand a life that’s just kind of going along in a balanced way. They need some drama. They need some real attachment or some real violence something REALLY happening so they feel they exist. So they create some drama in their lives. This is all based on this wrong conception of the “I” that we’re so addicted to, and at all costs are trying to prove exists. So we love the feeling.

Even jealousy. It’s such a painful emotion. But when we’re jealous, boy, there’s an “I” that exists. We’re not stuck in boredom. Are we? Boredom is kind of unpleasant. It’s better to be jealous than bored, because then you exist. At least that’s my observation, looking at my own mind.

Audience: So, Venerable, as far as the increase of the intensity—as years have gone on—the sex, the pornography, the explicitness of it. The level of the violence has increased. Is it just the grasping at self becomes even more reified… What’s the reason for the increase?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): What’s the reason for the increase, in our society, about pornography and violence and all these things.

They say this is a time of degeneration, and that means that people grasp at the wrong view of the “I” even stronger. And so the afflictions become stronger. So then, what used to be an up no longer is UP-enough. Making out at the drive-in isn’t good enough so you need the hard-core porn now. And the drugs are harder than before. And the violence on TV, and the violence we call entertainment, is so much more explicit. And it’s a sign of the degeneration of sentient beings’ minds in general, meaning that the afflictions are very, very strong. And we’re addicted to the afflictions. And the afflictions—if you’re going to talk about the body—when we have afflicted thoughts in our minds then the hormones start going. I mean, adrenaline. *Pow!* And then when you have adrenaline, that kind of goes right along with the big feeling of “I,” doesn’t it? “I really exist because I have this adrenaline going through me.” You know?

Audience: So how can we help other beings to really see that, that they don’t have to be addicted to these kind of rushes …

VTC: Okay, so how can we help other beings see that they don’t have to be addicted to it?

First we have to see that we don’t need to be addicted to it. That’s the most important one. That’s the big one. Because if we can let go of the stuff ourselves, then in our behavior we model something towards others, without even trying. But as long as our minds are completely captivated by attachment and aversion, trying to help others is like a person who cannot see leading others who are also visually impaired.

Of course, I’m uttering some words, but the real thing is I have to work with my own mind. Okay? Hopefully those words mean something to you, but they’re not my words, they’re Buddha’s words. So the real thing I have to do is work with my mind. Yes?

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.