The first noble truth and dukkha

Stages of the Path #88: The Four Noble Truths

Part of a series of Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner talks on the Stages of the Path (or Lamrim) as described in the Guru Puja text by Panchen Lama I Lobsang Chokyi Gyaltsen.

- The types of dukkha

- How having an awareness of all types of dukkha is necessary

- Developing real renunciation

We were talking about the truth of dukkha. Property tax is dukkha. Property tax exemption is not dukkha, but filing for it is dukkha. [laughter]

In talking about the four noble truths, when we look at the first one, dukkha—which is often translated as “suffering” but that’s not a good translation because “suffering” we always think of “ouch” and pain and so forth, and that’s not what is always going on in our lives. Rather, “dukkha” means “unsatisfactory.” There are different ways of speaking about the unsatisfactory nature of samsara. The first way has to do with breaking it into three categories. This is the format His Holiness talks about a lot.

-

The first one is called the dukkha of dukkha, or we could say the dukkha of suffering, the dukkha of pain. This is physical and mental pain that all sentient beings recognize as unsatisfactory and undesirable. Bad moods, mental pain, grief, physical pain, that’s all included there. Everybody, even the kitties, the grasshoppers, everybody recognizes that one. Wanting to be free of that level of dukkha, you don’t have to be a Dharma practitioner for that.

-

The second one is the dukkha of change. What that refers to actually is what we usually call pleasure. Here you see why translating dukkha as “suffering” doesn’t work, because then you say “the suffering of pleasure” or “the suffering of happiness” and that doesn’t make any sense in English. That’s why “suffering” isn’t a good word. It’s more the unsatisfactoriness of pleasure, meaning worldly pleasure, because every worldly pleasure we have, if we kept doing that experience that gives us pleasure it wouldn’t continue to give us pleasure. Eventually it would give us pain.

For example, when you’re hungry, like right now and you want me to finish talking quickly, the suffering of hunger is big. In ten minutes (or a half an hour, whenever I stop) and you start eating, at that point the dukkha of being hungry has started to go down, the dukkha of being too full is just starting, it’s just at its initial stages. So when that is happening we call that pleasure. If eating were actual pleasure then the more we did it the better we would feel. But if we were eating from now until this evening we wouldn’t even have to wait until this evening before we started feeling quite ill.

Any pleasurable activity that we can think of in cyclic existence, if we do it enough…. It’s more in the desire realm, so any pleasurable experience in the desire realm, if we do it enough it turns into outright pain and misery, even though at the beginning it seems to be pleasurable.

That’s the second kind of dukkha, and that is understood, in general, by spiritual practitioners of most traditions. People who are really practicing whatever tradition they have very deeply, they begin to see that sensual pleasure is unsatisfactory, and that restraint from sensual pleasure is called for.

-

The third kind of dukkha is pervasive dukkha, or sometimes “compounded pervasive dukkha.” What that means is just having the body and mind that are under the control of afflictions and karma. Just having that means that at any moment of our existence we are just walking on the edge of the cliff until circumstances change and we fall into the dukkha of suffering.

In other words, we may have a neutral feeling with the pervasive dukkha, nothing particularly pleasurable or painful, but our body and mind are not free, so we’re not free, and at any moment the circumstances could change and we experience pain. That state is unsatisfactory, isn’t it? That’s the meaning of dukkha, unsatisfactory.

This kind of dukkha—the pervasive dukkha—that is only really known by somebody who is able to analyze cyclic existence and see that afflictions and ignorance and karma are its cause. Because without understanding those as the cause, then you’re not going to see just having the body and mind under their influence as unsatisfactory. That’s why you’ll find in some faiths people might say, “Okay, searching for sense pleasure now is unsatisfactory, but we aspire to be born in heaven.” They don’t see that even if you’re born in that kind of heavenly realm where there is sense pleasure, it’s ultimately unsatisfactory because it can only last so long and then it turns into pain, or it ceases altogether.

We have to have an awareness of all three levels of dukkha and want to give all of them up in order to have actual renunciation (or the determination to be free).

The first one, like I said, everybody wants to give up pain. Second one, to renounce worldly pleasure, not because worldly pleasure is “bad,” but because if you do it long enough it becomes painful, and so it’s unsatisfactory. To want to be free of a situation where you constantly experience that because it just leads you into more dissatisfaction, that’s harder, isn’t it? Because our mind somehow still thinks, “This time lunch is really going to make me everlastingly happy.” “All the other relationships were bad, but this one is going to do it for me.” We get hooked there.

Then even if we get over that, then just seeing even the blissful states of samadhi in the form and formless realm–especially in the fourth form realm and above, in the formless realms, where you only have a neutral feeling–just even seeing that as disadvantageous and unsatisfactory, because it eventually ends, that’s even harder, because you could have given up attraction for sense pleasure but still be attached to that kind of bliss of those very deep states of samadhi where you have just equanimity. Wanting to give that up, and seeing it as ultimately unsatisfactory, is another big stretch for us.

When we see anything in samsara, anything whatsoever, as unsatisfactory and want to be free of it, that’s when we have real renunciation and the determination to be free.

We have to spend some time cultivating this determination to be free, because without the determination to be free then we’re not going to have any motivation to free ourselves and to practice the path that leads to that freedom. That’s why it’s really important that we do serious meditation on these three different kinds of dukkha. Even though our Western mind would much prefer to skip over that. It’s really important because doing this is what provides a lot of the fuel for our practice.

Also, it doesn’t make your mind depressed, but what it does is it makes your mind steady. Because when you have a good awareness of this then when the glittering pleasure of samsara kind of comes into your radar, you notice it as the glittering pleasure of samsara and as unsatisfactory, and so you don’t crave it, you don’t cling for it, you don’t seek it. Then your mind, even you haven’t realized emptiness yet, your mind still is able to stay fairly steady, you don’t go up and down like an emotional yo yo all the time.

Generating this kind of determination to be free has advantages right here and now, and of course for the long term it’s essential for the long term.

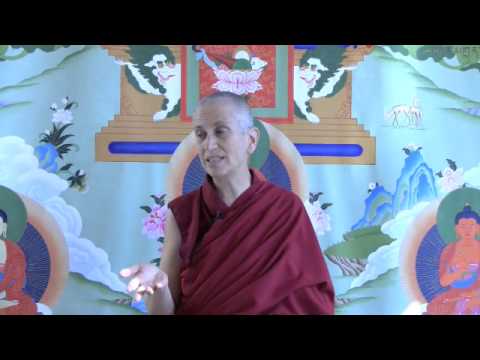

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.