Six root afflictions: Conceit and “I am”

Stages of the Path #104: The Second Noble Truth

Part of a series of Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner talks on the Stages of the Path (or Lamrim) as described in the Guru Puja text by Panchen Lama I Lobsang Chokyi Gyaltsen.

We were talking about pride and arrogance, remember? The first three kinds of arrogance occur when we’re comparing ourselves to others: to people who we’re equal with, to people who we’re better than, or to people who we’re not as good as. But in all three of these cases we come out the best. This clearly creates problems in our social relationships. And it also creates problems in our sense of wellbeing. Because when we get into this kind of thinking, of ranking ourselves, then it becomes very difficult to always maintain that rank, doesn’t it? If we put ourselves as best, then we have to continue to be best no matter what, even when we make a lot of boo-boos. So, it becomes quite stressful to be arrogant inside.

The conceit of “I am”

Let’s talk about some of the other kinds of conceit. There is one called the conceit of “I am.” This one is closely related to ignorance because it is based on looking at the “I”: “I am; I exist.” It’s just that conceit of “Here I am.” You know that one? [laughter]

We can really see that at the center of this conceit is the idea of there being an “I” to start with, and then of course that “I” is the center of the world. And every time we walk in anywhere, it’s: “I am; therefore blah, blah, blah, blah.” Everybody else should do everything centered around me. The tightness of holding on to “I am” with conceit is very, very uncomfortable.

Inflating ourselves in association with others

And then there is another type of arrogance where we are a little bit less than other people who are really good. At least this is one way of looking at this one. For example, say there is a conference of all these top-notch, extraordinary people in my field, and even though I am not as good as them, I am invited to the conference. This implies to myself that I am a whole lot better than all those other folks who weren’t invited. So, somehow we feel better by making ourselves big or important by being associated with someone else who is big or important.

This is often found in Dharma centers. People can sometimes think, “I am a disciple of so-and-so, and so-and-so happens to be a reincarnation of so-and-so. I am just a humble disciple, but I am associated with this great master who is an incarnation of a great master.” There is certainly nothing wrong with having these people as our teachers. What I am talking about is the conceit of trying to puff ourselves up by association with people who are better than us, even though we don’t claim to be as good as them.

The conceit of inferiority

In Precious Garland, Nagarjuna describes a similar type of conceit in a slightly different way, and this is the conceit of inferiority. So, instead of you being almost as good as people who are really good, or being associated with people who are really good, it’s the opposite. “Well, forget me; I can’t do anything well.” This is the one that really feeds into low self-esteem and creates that identity of “I just can’t manage.” Unlike the conceit where we puff ourselves up and think we’re better than everybody else and won’t take anybody else putting us down otherwise we’ll get angry, when we’re attached to this conceit of “I’m so worthless,” whenever anybody contradicts that and tries to praise us or tell us we’re worthwhile, we get very upset. Because we feel they’re not seeing us accurately. Then we mess up in the hopes that they’ll see us more accurately and see how hopeless we really are.

This is the one that comes up a lot of times when we talk about guilt. We may think, “If I can’t be the best, I’m going to be the worst. But somehow, I’m not like everybody else. Believe me, I’m really the worst.” This one is a big problem, too, isn’t it? You can see how all these different kinds of conceit revolve around self-image and how we think of ourselves. It’s a big problem, so just noticing these is already very good. And then we can begin to investigate and ask ourselves, “Is my self-image accurate?” Most of our self-image is based on rubbish, isn’t it?

Audience: When you ask yourself that question, and you’re using faulty mirrors to reflect the answer, how do you really begin to discern more accurately?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): When you’re used to faulty mirrors telling you who you are, how do you begin to discern? I think you have to ask yourself, “What are my talents, without comparing them to anybody else?” Identify the talents and abilities you do have. Then ask, “What are areas where I can use some improvement?” Remember, needing improvement doesn’t mean that you are worse than anybody else. When we do this we come to realize that even with our talents and abilities, we can also use some improvement. And even in the areas we can use some improvement, we have some talent and ability. So then we begin to see that we don’t need to make these things so positive and negative, and we get a sense that these things are always changing. We may be good at something at one point in our life, not do it anymore and forget it, and then not be able to do it. Or we may not be good at something and then practice it well and become good at it later on. All these things are just transitory attributes.

The basic thing is that we should use our talents and abilities to benefit sentient beings. Instead of considering them “my good qualities,” recognize that whatever qualities or abilities we do have came from the kindness of others who taught us and encouraged us. Therefore, we should use these qualities and talents to repay the kindness of others by using them to benefit society and benefit others.

You hear sometimes that at different universities some people won’t share their research. Or in the medical schools, you hear that someone will check out all the books on a topic so that no one else can use them. This happens in certain fields where people are only thinking of themselves and they don’t even want to share knowledge, which is very unfortunate, isn’t it? It even comes up in the Dharma. As I further pointed out, it states explicitly in teachings, especially on the bodhisattva vows, that not teaching someone because you don’t want to share your knowledge—because then they will know as much or maybe more than you—is definitely a transgression of the bodhisattva vow.

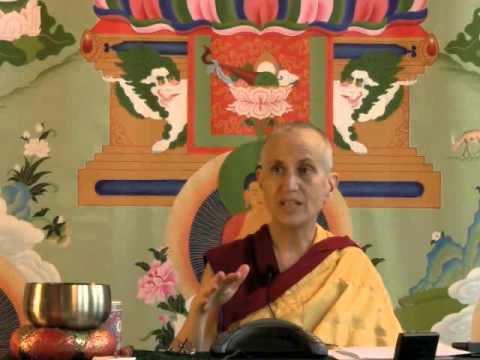

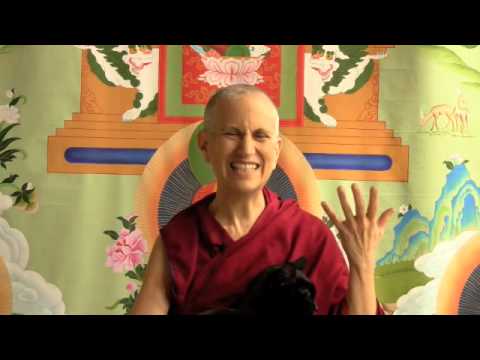

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.