I, me, myself and mine

Part of a series of teachings from a three-day retreat on the four seals of Buddhism and the Heart Sutra held at Sravasti Abbey from September 5-7, 2009.

- Taking advantage of this precious opportunity

- Importance of differentiating between virtue and non-virtue

- Physical, verbal, and mental karma

- Ignorance, the root of samsara, and dependent arising

- Different views self, labels and conceptions

The four seals of Buddhism 03 (download)

Motivation

Let’s cultivate our motivation and think for a minute of all the countless living beings throughout the universe, in different places, having different experiences with different bodies in different realms of existence. Think that all of this is caused by afflictions and karma and so all these sentient beings who want to be happy still find themselves in unsatisfactory conditions with either the dukkha of pain or the dukkha of change, and everybody is experiencing pervasive conditioned dukkha. So let a feeling of compassion arise for ourselves and others because we’re all in the same boat. Think of all these sentient beings that have been kind to us in previous lives and will continue to be kind to us. Let’s have compassion for everybody, and let that compassion motivate us to go beyond our own limitations, our own wrong views and wrong conceptions, so that we have a strong determination to understand the nature of reality; to use that to cleanse our mind of all defilements and their seeds and their stains, so that we can become fully enlightened Buddhas who are most capable of benefiting all living beings. So let’s make that our long-term motivation for being here today.

Cherish the opportunity

Now I’m going to try to talk to all my mothers and fathers from previous lives. That’s what I think when I give Dharma talks because my parents of this life weren’t interested in the Dharma. Then I say my parents of previous lives and future lives are interested—so I’ll talk to you. Hopefully in future lives my parents of this life will be more receptive to the Dharma and I’ll be able to help them in the Dharma then too. You can see how much is up to karma, isn’t it? So much is determined by karma and previous inclinations—such as what we’re attracted to, what we’re not, what we’re open-minded toward, what we’re not interested in, what we are interested in. We don’t come in as blank slates; and of course our present life conditioning affects us. Once we’re adults, if we’re fortunate enough to hear the Dharma, we can start reconditioning our minds. We can really see that things are very much influenced by our past intentions. It’s so interesting, isn’t it? Here are two people, the parents of this nutty Buddhist nun, and they aren’t interested in the Dharma. Yet I was born their child and became a Buddhist nun. Why in the world did that happen? It wasn’t what they had planned for me. So you can see that there are a lot of other influences going on.

That’s why it’s so important, once we hear the Dharma, to really start watching our mind as much as possible and to differentiate between what is virtuous or wholesome and what is not. Then really try as much as possible to put our mind in a good space to create more of that imprint so that that virtuous imprint will ripen in future lives. It doesn’t matter how old we are when we start practicing. The idea is, however old we are, to practice because the mindstream is a continuity and it goes on. Why we have this precious human life with the opportunity we have is really something quite precious. We don’t know if we’ll have this kind of opportunity and chance again. You can see even in this life circumstances can change. People may have very strong intentions to practice Dharma and then all sorts of things happen. I have one friend, really a very brilliant woman, an incredible translator. She was walking in a car park when one of the barriers came down and hit her on the head and her mental capacities are very much impaired now. Even though she had the intention, the love of the Dharma, had met the Dharma, everything like that, one small incident and her ability to practice in this life is kaput. That’s why, while we have our health, while we have the ability to learn and to practice and to reflect on things, instead of just taking it for granted thinking, “Oh, I’m always going to have this opportunity. I’ll do something else now and I’ll come back to the Dharma later.” It’s really important to cherish our opportunity and make good use of it while we have it. We don’t know if we’re going to be able to come back later because we don’t know what’s going to happen later on in this life. If we think like that, in that kind of way, then our life actually becomes quite joyful and quite meaningful and Dharma practice doesn’t seem like a burden. It seems like, “Wow, I am so lucky. I am so lucky that I have my mental and physical capacities, that I can wake up at five o’clock in the morning and meditate.” Instead of thinking, “Oh, five o’clock, who are they kidding?” But to really see our fortune at having this opportunity instead of thinking, “Oh, I’ve got to go listen to another teaching. My back hurts, my knees hurt. I want to go to the movies instead!” Instead of thinking like that, really see that because we don’t know how long we’re going to have the opportunity, do we? We really don’t know.

Now if we see the opportunity as something very precious, then like I said, our life becomes quite meaningful and joyful. We want to take the opportunity. It’s not a burden. It’s not, “Oh, I have to do this,” or “This is too hard. I’m dragging myself to enlightenment because I’m supposed to and I ought to and I should. And everybody’s going to judge me if I don’t get enlightened for them.” Instead of looking at things like that, our mind can be really quite happy. We think, “Wow, I have a precious opportunity and I don’t know how long it’s going to be in this life or future lives. I did many good things in previous lives to get the opportunity I have now!” One of the inmates I write to said that what really enters his mind when he’s practicing—and practicing in prison is not especially easy—is that he realizes that whoever he was in previous lives created a lot of causes for him to have this opportunity. He doesn’t want to blow it for whoever he was in a previous life that worked so hard. So he feels like he really wants to practice now. If we have that kind of insight then our attitude is very different.

Beginner’s mind

Sometimes when we’re around the Dharma a lot we become saturated and we take things for granted. Then we think, “Oh yes, I heard this teaching before. Yes, impermanence. Yes, yes, precious human life, there they go again.” We become like that. We become really saturated and we take the experience for granted. It’s important to make our mind fresh. I think in the Zen tradition when they talk about a beginner’s mind this is what they’re talking about. Come in and your mind is fresh, “Wow, I get to listen to this. Great.” Then you’re open-minded and you take it in. You’re eager. You have that fresh mind, that beginner’s mind—that isn’t saturated and exhausted and so tired of serving sentient beings. Like, “They say it’s going to be easier at enlightenment, but I don’t know.” Just think of how precious this opportunity is to serve sentient beings. We don’t always have an opportunity to serve sentient beings, do we? Sometimes we’re in too much pain ourselves in another realm, or the mind’s too obscured with stupidity in another realm, or too obscured with sense pleasure in another realm, and we don’t have the opportunity to serve sentient beings. So we should take the opportunity when we have it.

Four seals of Buddhism

Let’s get back to the four seals. When the Buddha was saying that all contaminated phenomena are dukkha, he was saying it in relationship to the mind. This is because the mind that is creating and perceiving these phenomena is a mind that is tainted by ignorance. In the Dasabhumika, the Ten Grounds Sutra, the Buddha said, “The three realms are only mind.” It’s a very famous quote. The three realms of existence: desire realm, form realm, and formless realm are only mind. And so there began a school of philosophical thought called the Cittamatra or the Mind-Only school. They take this quotation quite literally and say that the objects we perceive, plus the perceiving mind, all originated from the same substantial cause which was an imprint on the mind. They say there are no externally existing objects—that things arise due to imprints on the mind. Some glitch—holes come in that philosophy when you start to debate and ask some questions. The Prasangika Madhyamika school, which is said to be the most accurate of the philosophical systems, do not interpret “The three realms are only mind” to mean that the object and the subject both arise out of the same karmic imprint. Instead they take that to mean that there’s no absolute creator, but that things are created by the karma and the afflictions on the mindstream, by our intentions, by our attitudes. Saying that doesn’t mean that our mind is the only thing that creates things—because we can get very confused if we think in that way. There are external phenomena. There is an external world. But the things arise because we have the physical cause and effect system of physics, the biological cause and effect system of organic biology, the psychological cause and effect, and the karmic cause and effect. There are many different kinds of causality.

The way that afflictions and karma cause phenomena is not that the karma produces the metal that the bowl is made out of or the ceramic that the cup is made out of. It’s not like that. The mind doesn’t create the material. Don’t get confused. Rather there’s an intersection between the mind’s intentions and these other systems of cause and effect that occurs. At the time of the evolution of the universe, the karma of the sentient beings who are going to be born there influences the physical development of the universe. But the physical laws of seeds growing into sprouts, and oxygen and hydrogen combining to make water, these kinds of laws still function. Don’t go back to the Cittamatra view and think that this quotation means that there’s nothing outside, and that only the mind, the karma functions to create things. Rather, there’s an intersection there. The thing is, how we experience things, the way in which we experience them, depends a lot on our karma. For example, the system of physical causality may make an earthquake. Whether the earth is going to move and have so much tension depends on the law of physics and all the scientific laws. But us being there when the earthquake is happening is influenced by our karma and our actions. And if we’re there when the earthquake is happening, whether we’re injured or not injured in the earthquake is dependent upon our karma. There’s this intersection there between the different systems, and our karma is quite important.

Physical, verbal and mental karma

We have physical, verbal, and mental karma. The subtlest of those is the mental karma. This is because we have to have a mental intention before the mouth moves or the body moves. When we take precepts we start with controlling our physical and verbal behavior before controlling our mental behavior because that’s easier. It’s harder to control our intentions. But sometimes we can catch it before the intention becomes speech or the intention becomes physical action. At the first level when we are taking precepts, we take the pratimoksha or individual liberation precepts. These have to do with our physical and verbal actions. Of course, to keep those precepts well we have to start working with our mind. But we don’t break the precepts unless there has been a physical or verbal action. We don’t break them completely unless there has been a physical or verbal action. The bodhisattva and tantric vows, on the other hand, are higher levels of vows. Some of those, not all of those, can be broken just by the mind itself without the mouth or the body doing anything. So those systems of vows are much more difficult to keep. We can see here how the mind is involved with creating our unsatisfactory conditions. It’s the mind and the ignorance that keeps us involved in cyclic existence. During our lives we create all sorts of karma because we have all sorts of intentions. So what we want to be on the lookout for is at least not to create the very heavy, complete karmas. A complete karmic action is one where you have the object, you have a motivation to do it, there’s the action, and then there’s the completion of the action. For example in killing, which is the first one that we’re advised to abandon, there’s someone that you want to kill. There’s the motivation to do it and there’s an affliction behind that motivation. Then there’s the action of killing. And lastly, there’s the completion of the action—which is that the other person dies before you do.

Likewise with the ten nonvirtues, we have killing, stealing, and unwise and unkind sexual behavior. Those are three physical nonvirtues that we want to abandon. Then there are four verbal ones: lying, using our speech to create disharmony and division, harsh words, and idle talk. Finally, there are three mental nonvirtues which are coveting, ill will or malice, and wrong views. Those last three are very well-developed mental states. So it’s not just a passing thought of attachment, but you’re really dwelling on the thing you’re attached to so you really covet it. It’s not a passing thought of anger, but it’s really sitting down and plotting your revenge and having ill will. It’s not a passing, confused thought, but it’s a very stubbornly held wrong view that makes the mind very closed. We want to avoid those kinds of actions because when they’re complete—with all the factors complete—they put the seeds on our mindstream.

Time of death

Then what happens at the time of death is that we all have it planned out, right? You have your own little death scene all planned out, the perfect way you want to die. Have you ever thought about that? How many people have thought about their perfect death and how we want to die? So we have our little perfect death scene. Forget it. That’s just our grasping that thinks that we can control the world and we’re going to control all the people around us. What our mind is thinking is, “I’ve been trying to control everybody my whole life, and they haven’t cooperated. At least at the time of death, I’ll be successful with them. They’ll do it because they’ll know I’m dying.” Forget it, folks. We’re not going to be able to control other people at the time of death. The question is are we going to be able to control our own mind at the time of death? Can we control our own mind while we’re doing the breathing meditation for ten minutes? You know we can’t, can we? Our mind is all over the place. So thinking that we’re going to have this perfect death scene where we’re going to be in complete control, and everybody else is going to finally do what we want them to do, it’s not going to happen. If we can’t do it while we’re alive, how are we going to do it when everything is so confused and we realize we’re departing from this life? People tell me, “Oh, I want to practice dream yoga.” But if we can’t focus our mind when we’re awake, how are we going to do it when we’re dreaming and we have less control? Just think about it. We’ve got to be practical. Getting these airy-fairy ideas we have isn’t going to work. We’ve got to get our feet on the ground here.

Twelve links of dependent origination

What happens at the time of death? There’s something called the twelve links of dependent origination—which actually comes in the Heart Sutra. In the twelve links of dependent origination they talk about how we are born and die, born and die—again, and again, and again. What happens at the time of death is that craving arises. Now, we have a lot of craving while we’re alive, don’t we? We crave a ton of different things. At death time we crave to remain in this body. We crave this life. We crave the familiarity of our idea of who we are, and of everybody we’re attached to, the whole scene we’re in. Even though it’s unsatisfactory, even though it’s miserable, we don’t know anything else—and we’re terrified of separating from it. Our mind goes, “If I don’t have this body, who am I going to be? And if I’m not in this particular social situation, with people relating to me in this way and me relating to them in that way, who am I going to be? If I don’t have these possessions that describe my self-image, who am I going to be?” So a lot of strong craving comes at the time of death. This craving acts as the water and fertilizer on some of our karmic seeds and makes them start to ripen. The seeds that are most likely to ripen are the ones where we have a complete virtuous or non-virtuous action. And if, when we’re craving, there’s also a lot of holding onto this life—or maybe the mind is angry. We’re dying and we’re angry at the doctors because they aren’t God and they haven’t saved us. Or we’re angry at our relatives because of something they did thirty years ago—whatever it is. If we die with that anger, that’s going to act as fertilizer for a negative karmic seed to ripen. If we die with a mind that is rejoicing in our own and others’ virtue, and a mind of kindness, that will make a positive karmic seed start to ripen. But to have a virtuous mind at the time of death, because we’re very much creatures of habit, means training our mind to have a virtuous, wholesome attitude while we’re alive. So we just have to look at our mind and say, “How often do I have a virtuous attitude compared to how often am I grumbling and griping and angry and vindictive? Or just plain old spaced out?” Zoned out on the TV and the Internet and the drugs and alcohol and driving around because we don’t know what to do. We’re very much creatures of habit. We have to ask ourselves how we’re living—because that’s going to influence how we die.

Self-grasping

So we have the craving. At a certain point it becomes evident to us we’re not going to be able to hold onto this life. Then what we do is we grasp to have another life: “If I’ve got to separate from this one, I want another one. I want another ego identity.” There arises this self-grasping at this big “I,” “Me!” “I am here!” There’s this feeling like you’re going to go out of existence because the mind is changing and you’re separating from the body. There’s this fear, “I’m just going to cease to exist.” So there’s this grasping, “I want to exist, I have to exist. A body’s going to make me exist.” Or, “Some kind of ego identity is going to make me exist.” That grasping together with the craving really acts as the fertilizer that makes a previously-created karmic seed start to ripen. That karmic seed, as it’s starting to ripen, is the tenth link [of the twelve links of dependent origination] which is called existence. This tenth link of “existence” is giving the name of the result to the cause. This is because even though you haven’t been reborn yet, that seed is going to create another existence in samsara. And then as that seed is ripened, at a certain point when it becomes possible to enter into a new body, boing, there we go and the next life begins. We’re reborn again and again and again in this way without end as long as ignorance is there—because ignorance is the root of samsara.

Ignorance is the root of samsara

We talked a little bit yesterday about how ignorance is the root of samsara. Let’s approach it a little bit differently today. We can see that a lot of greed, clinging attachment, and anger cause suffering, right? Would people agree with that? When you have a lot of clinging—your mind is just clinging and sticky and greedy, it causes suffering. When the mind is angry and hostile, it causes suffering. Now how do those attitudes, or those mental states, those emotional states of attachment and anger arise? What are they based on? What fuels them? How come they’re there? Let’s look at attachment first of all. Let’s say I’m attached to my flowers. I’m just saying flowers because they’re here. This could be your car, this could be your partner, this could be your kids, this could be your social status, it could be your body, it could be whatever it is. I’m attached to my flowers. Well, before somebody actually gave me the flowers they were just flowers growing in a garden. I wasn’t especially attached to them. When you’re walking through the garden, you know, you enjoy them. They’re pretty. But there’s not this sense of, “They belong to me.” As soon as someone gives me the flowers, as soon as we buy the car, as soon as we get engaged, as soon as the baby comes out, as soon as we get the promotion, as soon as we get the trophy or acknowledgement, whatever it is—then the thing becomes “mine.”

This is mine!

What happens when I label things “mine”? There’s a big distinction between others and me; and what belongs to you and what is mine—because if it’s mine, it’s not yours! And you better be very careful about how you relate to things that are mine. If you interfere with the things that are mine that give me happiness, whether it’s a person or a situation or praise or reputation or material possessions, if you interfere with it, look out! Now, has anything actually happened to the flowers themselves from their side? From when they were in the garden to when they became mine? They got cut, but they’re still basically the same flowers, aren’t they? Okay, they’re more wilted now. But basically there has not been any big physical thing that’s changed the nature of the flowers. So what happened? The mind labeled them, “mine.” So it’s just a label, “mine.” “Mine” is just a concept. There’s nothing inside these flowers that makes them mine, is there? You send them to a lab to be tested, are they going to find “mine” inside there? Are they going to find “these belong to Thubten Chodron” inside those flowers? No. It’s just a label that we’ve given to the flowers. But that label has a lot of meaning. What gave that label the meaning? Our mind. Our mind gave that label the meaning. So when I call it “mine,” it becomes a big deal. There’s some grasping there at “me,” isn’t there? There’s already some grasping at this notion of a real, solid, truly existent “me,” who now has become the owner of these. Somehow, mystically, magically, I have permeated these flowers with mine-ness that they inherently have. And so because of that, because they’re mine now, I’m very attached to them in a way that I wasn’t attached to them when they were in the garden. Now when people interfere with my flowers, I get upset. This is because there’s this real me who’s deriving real pleasure out of these real flowers. And a real you is interfering with them. So then anger arises. You can see that below the attachment and below the anger, there’s this notion of a real, solid, truly existent “me” who exists.

Self-grasping of persons and self-grasping of phenomena

That is called “self-grasping of persons.” That’s the grasping at “I” and “my,” the self-grasping of persons. When I’m looking at the flowers and I think they have some essence on their own—they truly exist, or my body truly exists, or something like that, it’s called “self-grasping of phenomena.” Self-grasping of phenomena means all the other things that are existent besides persons. Now, we have to look at the wording here. This is because we have in self-grasping of persons and person, one way of using the word “self.” Self, person, I, all these things are synonymous. The self is the person. We each have a self, hence self-grasping of person—as opposed to self-grasping of phenomena. The word “self” has different meanings in different contexts. This is quite important and if you remember it, it will save you a lot of confusion. The word “self” has different meanings in different contexts. When we’re talking about myself, ourselves, my I, your I, that way self is synonymous with persons. But in another context, “self” means the object that is negated in the meditation on emptiness. In other words, self means inherent existence. Self means the fantasized way of existing that we have projected onto people and onto things. So when we talk of the self of person it means the inherent existence of persons. When we say the self-grasping of phenomena, it’s the grasping at inherent existence of phenomena. Similarly, when we generate wisdom that realizes no such self, no such inherent existence exists, that becomes the selflessness of persons or the selflessness of phenomena. So you have to figure out what self means in different contexts. It would be so easy, wouldn’t it, if a word only had one meaning—period. We’d avoid a lot of confusion. But even in English things have multiple meanings; one word has multiple meanings that sometimes make it very confusing. Take the word “sanction.” This word always puzzles me. Sometimes sanction means you impose sanctions and you’re not going to do business with somebody. Sometimes sanction means you approve. So it has two opposite meanings, doesn’t it? You know, it’s very confusing. I can’t even figure it out.

The common meaning of empty and selfless in the four seals

As we move into the third of the four seals—empty and selfless, we need to know the meaning of empty and selfless. Here we’re going to get a little bit into the tenet systems, but not too much. The four seals are principles that are accepted by all Buddhists. I mentioned before that within Buddhism there are different tenet systems, so there are sometimes different beliefs and different assertions about the nature of reality. Since in general the four seals are accepted by all the traditions, then the common meaning of “empty,” in the terms of the four seals, is that there is no permanent, partless, independent self or person. We talked about that yesterday. And then “selfless” means there’s no self-sufficient, substantially existent person—which is the person that’s the controller. These are the commonly accepted things by all the Buddhist tenet systems. The Prasangika Madhyamika actually have a different assertion, and while they refute a permanent, partless, independent self and a self-sufficient substantially existent self, they say that both of those are gross levels of fantasized meaning, and that actually the subtlest level is an inherently existent self—not only of the person but also of phenomena. So from the Prasangika viewpoint, “empty” and “selfless” have the same meaning of the lack of inherent existence.

We’re not expected to understand the first time we hear it!

There are a bunch of terms here. Let’s go back and unpack them. When you’re first learning this, you have to learn the terminology, and it can be very confusing at first. But we’re not expected to understand everything the first time we hear it. If you can, get some kind of an idea and learn the terminology. Then the next time you learn a little bit more. It becomes a little bit clearer. You have a better idea of what the concept means. Then the next time you hear it you can pay more attention to different kinds of things. So don’t get worried if everything’s not completely clear the first time you hear it. It’s expected that this is going to take repeated listening—which is why we listen to the Dharma repeatedly, and why it’s not so good to say, “Oh, I’ve heard that teaching before, I got it,” because we just might not have.

Negating the permanent, partless, independent self

The permanent, partless, independent self that is the very gross object of negation, the very gross object of person that we’re saying does not exist, is the idea of a soul or a self that is totally separate from the body and the mind. And it’s an idea. There are different levels of misconception, different levels of grasping. Some grasping is innate—it goes with us from life to life. Even animals and all the beings have it. Some grasping we human beings create with our conceptual mind, and that’s called acquired grasping or acquired ignorance. This is because we acquire it through learning incorrect philosophies, or incorrect theories, or incorrect psychologies. This idea of a soul, permanent, partless, unitary, independent of causes and conditions is an idea that we human beings have created. It’s not even an innate grasping that goes with us from life to life. But you can see how, as we talked about yesterday, we got this thing instilled in us when we were little, and we believe in it, and it provides a lot of emotional comfort. We can think of all sorts of reasons why such a soul exists. God created it. There’s an absolute creator. God created this. We have a soul that is beyond the body and mind—that does not depend on causes and conditions. Even when the body falls apart and we lose our mind, the soul is still there and the soul gets reborn somewhere. We can make up a whole religious system or philosophical system based on that idea.

But as we did yesterday, if we really examine things, we have to ask, “Can there be a self that is permanent and unchanging?” That becomes very difficult. Even though we sometimes have the idea that there’s this permanent self that just bumps into things, actually, when we think about it, we realize that due to everything we bump into we change. Don’t we? We are a conditioned phenomena. We don’t think to ourselves when we say “I” that, “I am a conditioned phenomena, I exist only due to causes and conditions.” We don’t have that feeling. To think of the self that is unitary—without any parts, without a body, that doesn’t have a mind, that is something separate from those—is also very difficult to sustain when we analyze it. Think of the self that doesn’t depend on causes and conditions, that’s not created, that doesn’t change moment by moment. When we examine it, “Yes, we change moment by moment.” All the Buddhists’ systems agree that kind of self [permanent, partless, unitary] doesn’t exist. This was the self that was propounded by many of the non-Buddhist philosophical systems at the time of the Buddha. When you read the Pali sutras, you’ll see the Buddha’s always engaging in dialogue with these people, “Let’s have a debate and see, and really talk about it,” and then he explained why that kind of thing can’t exist. (People at the time of the Buddha were also asking, “Is the universe infinite or finite? Is the Tathagata, the Buddha, permanent or impermanent? Is the self permanent?” They were very similar kinds of questions.) Okay then, so we negate that one.

Self-sufficient, substantially existent self

The common understanding for all Buddhist schools is that “selflessness” means the lack of a self-sufficient, substantially existent self. What does that mean? This is a person—the feeling of “I” that we have—that controls. The “I” is a controller of the body and mind. It is self-sufficient. It’s substantially existent. It’s there and it controls the body and mind. It’s kind of mixed in with the body and mind. It’s not seen as a separate soul. It’s mixed in with the body and mind, but it’s the ruler. This is the one that controls—that thinks we can control our body, that thinks we can control our mind. But when we look, is there any kind of self that exists like that, that’s separate and can control the body and mind? There isn’t such a self. All we find is a body and a mind. We don’t find any super thing above and beyond it that’s controlling it.

The I that exists from its own side

Now, from the viewpoint of the Prasangika negating these two: the permanent, partless, independent and the self-sufficient substantially existent person is not sufficient. Prasangika says negating them are steps on the way. They assert that underlying both of those wrong conceptions of the person, or wrong graspings of the person, is the notion that there’s some objectifiable locus for who we are—some essence that is really me—something that, when you take everything away, is truly the essence of me-ness. So the inherently existent I, or as it’s also called “the I that exists from its own side,” exists from its own side without depending on being labeled by the mind. It has its own inherent nature that doesn’t depend on anything conceptualizing it and giving it a label and creating it in that way. But rather it radiates its own inherent nature, something that makes it “it” from its own side, without depending on the mind.

The basis of the label

Now, when we look around and we look at things, for instance when we look at the flower. It seems like there’s a flower in there, isn’t there? Yes, there’s a flower essence. We don’t look at the flower and think that flower depends on being mentally labeled, do we? We just think there’s a flower there. There’s something in this that makes it a flower—independent of the mind. But then we examine (and here’s more terminology) the basis of the label. The basis of the label is the collection of parts, the basis of designation, the basis of the label. They all mean the same thing. This is the basis of designation. It’s a collection of the parts. But, is the collection of parts itself sufficient for this to be a flower?

Labeling, conception, and dependent arising

If we separated all the parts and put the petals here, and the stamen and pistils—and all those other things that I learned in fifth grade and I forgot what they mean now. You put all those other things there piled in a heap. Is that the flower? It’s not. But has anything been added to that collection of parts when it’s put in this shape? No, it’s just a rearrangement of the parts. So this shape, this configuration itself isn’t the flower. It’s when our mind looks at it, picks out these things as details, conceptualizes this as a thing and gives it the name “flower.” At that point it becomes a flower, it becomes a flower at that point. So there’s nothing in it that actually makes it a flower. But its being a flower depends on our mind labeling it, and this thing being able to perform a function that we’re assigning or the meaning that we’re assigning to that word. We could call this “ickydoo.” So, I mean, in another language you could call it ickydoo, but it could be an ickydoo as long as it performs the function of what you’re assigning the sound ickydoo to mean, okay? In other words, we can’t call a thing anything we want to, and change it and make it into what we call it. But a thing doesn’t become something until we give it a name and believe it to be that way.

Early childhood perception

To me this fits in with the little bit I know about early childhood development and early childhood perception. When babies are born, babies’ perceptions are just of colors and sounds and everything’s mixed up. And when a baby cries, the baby doesn’t know that it’s making the sound. So babies, when they hear themselves cry, will often get frightened by the sound. They don’t have the concept, “I’m making this sound.” And when babies lie in their crib and there are these little things floating above them, they don’t have the idea, “Oh, there’s an angel. Oh, there’s a frog.” When babies see their mother and father, they don’t have any idea of what “mother” means or what “father” means. They don’t think, “My body came from these people.” All they know is, “Oh, there’s warmth, there’s comfort, there’s food.” But they don’t have the conceptualization in their mind of all these being discrete objects.

When the baby looks at a flower, beside the fact that it doesn’t have the language to label it “flower,” it doesn’t even have the idea that this is a discrete object. This is because all the colors are blurred together. The color of the flower is blurred with this and that. The baby doesn’t know which things are in the foreground, which are in the background, which things belong together. As we get older, as the baby grows up, we develop more conceptual ability, and we begin to put pieces together and make them into objects. Then we label. We give them labels and then they come to function.

The flower lacks its given meaning

We have a definition, we have a label and it’s societally agreed upon most of the time, but when it isn’t, we quarrel about it. We create these objects and then we impute more and more meaning on all these things. “This flower is beautiful, this flower is mine, this flower gives me pleasure, this flower symbolizes how successful I am as a human being.” We impute so much meaning onto it. But the flower in itself completely lacks all that meaning of attachment and aversion that we put on it. It even lacks having the essence of flower itself.

The example that is very often given, when we talk about things being merely labeled, is the presidency. We look at Obama right now and say, “He’s the president,” as if he’s the president from his side. But actually he wasn’t born the president. He only became the president when we elected him and after he was sworn in. At that time, he really has the name “President,” and he’s able to perform the function of president and he actually becomes the president. But before we collectively give that name, he isn’t the president. So many things depend upon being merely labeled.

How about the idea of the flower becoming mine? Why does it become mine? Well, it became mine because somebody gave it to me. We’ve all agreed that when one person, who’s the owner, gives something to another person, that new person becomes the owner. And that new person has now certain privileges. So we have the idea of what “mine” is and we respect something that belongs to others—supposedly. We see that when people don’t do that we have a lot of difficulties in society—difficulties, for example, such as stealing. All of our minds agree upon all of these things and imbue them with some kind of meaning. So the idea is that things exist in relationship to the mind. They don’t exist out there on their own, having their own essence independent of any mind that perceives them.

Disproving inherent existence

Because things are dependent, they are not independent. This is because dependent and independent are mutually exclusive. If things are dependent, they’re not independent—and independent is the meaning of inherent. So “independent existence” and “inherent existence” mean the same thing. It means independent of any other factor, able to stand on its own under its own power. Here’s where we learn that if things were independent, they would have to be permanent. This is because if they’re independent, they’re independent of any other factor. It’s not only the mind that conceives and labels them, but also they’re independent of causes and conditions. Anything that’s independent of causes and conditions is permanent. If things were really inherently existent, then they would have to be permanent—and they aren’t. This acts as a rebuttal that disproves inherent existence.

What we pile upon the labels and objects

We’re getting into the third of the four seals. We’ll talk a little more about nirvana next session. But now, try going around and looking at how your mind conceives and labels things. It’s very interesting how actually a lot of our education is learning labels. When we talk about a court case, we talk about deciding what label we’re going to give: innocent or guilty. Wars are fought over labels—do you call this piece of dirt mine, or do you call it yours? So, how we label things and how we relate to the labels is very important. There’s nothing actually wrong with labeling itself. Labeling allows us to function together as human beings, sharing things. Labeling is not the problem. But when we think that the objects exist from their own side independent of the label, and then we pile all sorts of other stuff on top of it, then that is what breeds attachment and anger. And when other people pile different stuff on top of the label than what we’ve piled, they’ve piled “mine,” and we’ve piled “mine,” then we fight over whose it is.

Okay, so keep this in mind and we’ll continue this afternoon. Sorry we didn’t have any time for questions this morning.

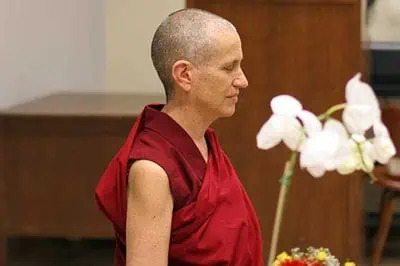

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.