Create karma, accumulate merit, apply antidote

Part of a series of teachings given at the Winter Retreat from January to April 2005 at Sravasti Abbey.

Something to look at is the negative karma that we’ve created in relationship to our spiritual masters, in relationship to the Buddha, to the Dharma, to the Sangha and to our Dharma friends; the people who are really encouraging us in virtue. We need to look at what kind of negative karma have we created in this life that we need purify. And even if we haven’t created things in this life, when we study some of the descriptions of negativity, who knows what in the world we did in previous lives? Sometimes you hear the stories of these things or you look at the Bodhisattva Vows—the Bodhisattva Vows contain a lot of these things to abandon—and you say, “Who in their right mind would ever do that?” Let me tell you, if you hang around the dharma long enough, you see people doing these things; it’s absolutely amazing sometimes what you see people do. And even at the time of the Buddha, lots of his disciples became arhats, but some of them were really off the wall. Others shaped up by the end and became arhats, but some of them started off pretty good and then ran out of merit and did some pretty strange things.

Thinking about this in terms of the Buddha, criticizing the Buddha in any way or making sarcastic comments can come from a mind that has no exposure to the Dharma, that has not heard the Dharma and so hasn’t had the opportunity to think about it and see the truth and accuracy of what the Buddha was saying, and makes all sorts of negative comments. Or using Buddha statues to make a living, selling them like you would used cars. “How much can I charge for this Buddha statue so that I can go the Caribbean for holiday?” Regarding the offerings we make on the altar—though I’ve never heard this in the scriptures, it makes sense to me—that we should request permission to take the offerings down. We’re not just giving something to the Buddha and then taking it when we want it, that’s not a pure offering—that’s like stealing from the Buddha. “I’ll put it on the altar, until it’s time for dessert, then take it off the altar”. People in Singapore sometimes did that. Oh, I really got after them—they didn’t know.

It’s important to treat the objects representing the Buddha in a respectful way. Not that we’re worshiping idols but because they represent the Buddha’s qualities which we aspire to attain. We need to investigate our negativities with the Dharma, criticizing the Dharma, or being one of these flaky teachers who makes things up and passes it off as the Dharma—teaching something that looks like the Dharma but isn’t. Or disregarding certain things—there may be things in the Dharma that we don’t like, so we just say, “Well, the Buddha didn’t teach that”. Or, “The Buddha didn’t really mean that”. You know how we don’t like hearing teachings about the lower realms, so we decide, really it’s not important, we can just ignore it. We also don’t like hearing teachings about negative karma, do we? Well let’s just ignore that too. Who knows what we did in previous lives, we might have been one of these flaky teachers. [A brief exchange to make sure the Mexican students understand the slang, ‘flaky’—“Charlatananada”—a phrase coined by Patricio in Xalapa, Mexico. A new word was offered in Spanish—maestros chafas.]

Who knows, we could have been somebody like this in a previous life; using the Dharma to make money, modifying the teachings to suit followers and get a lot of offerings. Who knows what we could have done in a previous life? Anything that you see around you can think, “I may have done that in a previous life.” It’s a good idea to purify and make a strong determination not to do that again. Whenever we see someone doing any kind of negative action, instead of just blaming, blaming, blaming—think, maybe I did something like that in a previous life. Instead of being so pre-occupied that what the other person is doing wrong, think, “Oh, maybe I did that, so it’s very good that I do some confession, even if I can’t remember doing it. You know, we’ve done everything in samsara. In any case think, “I want to make sure I don’t do it in the future. So if I do the Four Opponent Powers and especially make a very strong determination that I will never mislead people in the Dharma intentionally and I pray that I never mislead them unintentionally or accidentally also.”

Doing that helps us in the future not to become like that. And it helps us stay focused on practicing the Dharma ourselves instead of pointing the finger at somebody else. Because we can go through and point the finger, but there’s no end to ‘maestros chafas’ and wrong views which gets us into pointing the finger at everybody, and basically it’s arrogance; the conclusion is I’m the best one. All these other people are bad and if you’re going to find something bad, you’ll find something bad in great masters also. The conclusion is, “Well, I’m the best one!”—then we make our own path to enlightenment. The Buddha said that when a monastic goes into town he or she is not concerned with what other people have done or left undone, but concerned with what they have done or left undone. Or when a monastic goes into town they are like a bee that goes from flower to flower extracting the nectar but not getting stuck in the mud. What this means to me is to be able to see people’s good qualities but not get stuck in pointing the finger at them. We might recognize they have some faults, and do what I just said, an say to yourself, “Oh, I may have those faults too. I may have done that in a previous life. I don’t really want to ever do that.” And make a strong determination not to do that. Or instead of, “they have such and such fault. Oh, do I have that fault in me at all?” Ho, ho, ho, ho! “So and so is so arrogant, so and so is so moody.” What about me? Am I arrogant, am I moody? I feel good, I feel bad. You look at me and say good morning and I get angry. Good reason for keeping silence. [VTC takes an informal poll of who’s moody in the morning.] But when we see this to ask ourselves, to what extent am I moody or to what extent am I grumpy? Or to what extent am I arrogant or full of attachment or singing my own praises. Use the Dharma like a mirror; turn the mirror to look at yourself. “Oh, I’m so beautiful, there’s Buddha nature, but there are some pimples too; a lot of pimples, I’ve got to clean them up.”

Then there’s negative karma with the Dharma—making up teachings or criticizing the Dharma, not treating Dharma materials respectfully; using things with Dharma words and then throwing them in the garbage or putting your glasses, tea cups, pens, pencils and everything else on top of your Dharma books, or putting your Dharma books on the floor or stepping over them. It is basically a mindfulness practice of respecting the written materials that describe the path to enlightenment.

Retreatant (R): I would like to ask about underlining, highlighting or making notes in Dharma books, if this is okay as a method of Dharma study?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): I think it’s okay to write in Dharma books if your motivation is that you want to learn the Dharma. If you were scratching out words you didn’t like, that would not be good. Lama Zopa also said you can also think that you’re offering color to the Buddhas when you underline or highlight a text. I often do this myself, to remember important items or to find a quote easily. So much depends on our motivation. They tell the story about treating the Buddha statues with respect: Somebody who was walking along the road saw a Buddha statue on the ground. They immediately thought that it was not good to have the Buddha statue on the dirt and found an old shoe nearby and put the statue on top of the shoe—yes it’s an old shoe but at least it is up off the ground—and did that as a way of respecting the Buddha. Later, it was raining and someone else came by and saw the Buddha getting wet and put the shoe over the Buddha to protect it from getting wet. We might look at these actions and ask why a dirty shoe under or over the Buddha? However, their motivation was one of paying homage and respect. It is a similar thing here about marking Dharma materials.

R: On a related topic, it is sometimes very difficult to get Dharma books in Mexico, so often people want to make copies of them.

VTC: Yes, the photocopying of printed materials. This pertains not just to Dharma books but to other materials as well. I’ve discussed this with some of my friends, but let me give you my ideas on it. If the book is out of print and you can’t it get it anywhere, then I think it’s okay to photocopy. The thing is, why do people photocopy the book rather then buy the book? If it’s because they don’t want to pay for the book, it becomes a way of stealing because the company and author should get some income. By photocopying because you don’t want to pay, it’s a form of stealing. Sometimes even with books that are still in print, I find myself photocopying something I want to give to students because I clearly can’t buy enough books to give to all the students. But what I try to do is to say who wrote it and where it comes from and I’m giving you this one section but if you want the whole book here’s how to get it. In that way, I try not to steal from the author. Or sometimes you write to somebody and ask if you can make copies. Photocopying a chapter is quite different that photocopying the whole book. And if it’s a book that‘s hard to get and you can’t get it anywhere and your motivation isn’t to steal or to avoid paying, but rather to spread the Dharma…a lot depends on motivation here. It’s a similar thing to making illegal copies of computer programs and applications. In some countries this is just standard practice, you make an illegal copy, when in fact it’s a form stealing—it doesn’t belong to you. If it’s one book that’s hard to get, I think that’s okay. Again, it all depends on your motivation.

Negativities with the Sangha can include criticizing the Arya Sangha or criticizing the monastic community. People make all sorts of remarks nowadays, “If you ordain you’re just escaping relationships and denying your sexuality.” People say all sorts of ridiculous things like this—that’s putting down the path the Buddha taught, isn’t it? So, I think it is important, now, not all monastics are perfect, we aren’t perfect. But, what you are respecting when you respect the Sangha, is the pure vows in that person’s continuum. And the part of them that keeps their pure vows, you’re respecting that and taking it as a good example. And the part of them that has faults—maybe they lose their temper, gossip, or whatever; you take that as an example for yourself of what not to do. You can talk about the actions that person is doing, but that is quite different from criticizing the whole Sangha community.

Things in relationship to our spiritual mentor: there are all sorts of things in terms of etiquette. I tend to be very informal so I find often that my students don’t know how to act when somebody like Rinpoche (Lama Zopa) comes. You don’t know what the etiquette is because I tend to be quite informal with people. But, it is good sometimes to learn the etiquette. The teachers that like to be treated in a formal way, you treat them like that. The teachers that like to be treated in an informal way, then you go according to how they like to be treated. One of my teachers, Geshe Jampa Tegchok, he’s a very highly respected Lama, the former abbot of Sera Je. And when I go into see him he sits on the floor and he makes me sit on a chair. For me this is horrible; to sit higher then my teacher, never ever, ever. You know? But he makes me do it. So I have to do what he says. And then he cooks food for me. I mean again, what is my teacher doing cooking food for me, especially a former abbot, somebody who’s teaching me the path to enlightenment—what’s he doing cooking my dinner? I should be cooking for him. But, this is how he likes it, so I go along. I have to. I always make an effort and then he stops me.

But then other teachers… I mean Lama Zopa, you come in and of course you bow and you sit lower, there’s no question about it, Lama is quite formal. So, there are things like that to pay attention to. Making your teacher’s mind unhappy is another issue. You know, getting angry at your teacher; yelling, screaming, criticizing, or blah, blah, blah. You may not agree with things your teacher says, so you discuss them with others. Having a good relationship with you teacher doesn’t mean you take everything they say with undiscriminating faith and do it. No, you discuss and ask questions. But that is quite different from criticizing, bad mouthing, spreading rumors, fighting and quarreling. But in general, in terms of etiquette, when you’re dealing with a western teacher it is different from when you’re dealing with a Tibetan teacher. Some of the things are Tibetan, some things are western, you have to learn. Give some thought to how you relate to the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha and your spiritual mentors. Also, your spiritual friends; how do you treat your other Dharma friends? Do you treat your Dharma friends respectfully, or do you compete with them? Are you jealous of them? Do you get involved in all sorts of politics?

Letters from inmates

I have lots more issues to cover; I could go on all night, but maybe I’ll stop at that. Oh, I got a letter from Gunaratana, who’s one of the inmates doing the Vajrasattva practice. I wanted to read what he said to you.

R: What is his name again, Venerable?

VTC: Gunaratana, that’s his refuge name. He changed his name.

R: Ahh, he wanted it professionally changed?

VTC: Yeah, he officially changed his name. In his letter, he says, “Here are a few points and/or realizations that have come to me during this Vajrasattva retreat. #1—Negative things that I have done, things that I totally forgot about are suddenly resurfacing.”

Anybody else having that experience? [laughter of recognition]. “Sometimes these memories are just there, but at other times I find that I am overwhelmed with a sense of remorse and sadness over my past actions. Interestingly though, I have found that when these past actions and/or hurtful speech arise in my consciousness, the focus does not seem to be on me, but on those to whom these negativities were directed at. In that, their reactions and feelings seem to be the focus of my conscious memories of these events.”

Ok, so what he’s finding out is that he actually cares about other people and he’s realizing that his actions affect other people. “But, this is even more interesting to me. As soon as I acknowledge these past actions, and offer them up so to speak, they diminish and fade away. For me, it seems that I must go through this process of: seeing them, having remorse for them, acknowledging, offering and letting go. Afterwards, I have been experiencing a feeling of being cleansed, being purified—a pure happiness.”

Is that what is happening to you too? Sometimes when your negative stuff is coming up?

He writes further: “#2—The more I do this retreat, which is a kind of continuation to the Vajrasattva practice you already had me doing, the clearer my visualizations are becoming. For a while I could do nothing but imagine a feeling of having the Buddha sitting on my head, but following your advice I am finding that the more persistent I am in my daily practice, the easier it seams to get. Of course the wonderful photo of Vajrasattva, that Jack sent has helped me out a lot; so things are going very well; very revealing and very inspiring. #3—How very caught up I am in name and form. I attribute this to several issues, but during this retreat I have found Je-Song-Khapa’s warnings about teachings and teachers to be more relevant in my life, these days more then ever before. So, I must be careful with what I associate myself with. The eight worldly concerns are very insidious and subtle, in ways we don’t even consider in our daily lives.”

Those are his comments about retreat. Nice huh? Then, one other inmate, Bill Suesz, said that he was only able to listen to the tape once, before he had to give it up, or they took it away. I’m not sure what happened so we need to write and ask him. He is the one at St. Anthony’s in Idaho, write him and ask him what happened. And see if you can send him another one. Because I think it would nice if… he said it was very helpful for him to just hear someone leading it and talking about it. Bill, and I don’t know how to say his last name, [spells out Suesz].

Emptiness of inherent existence and attachments

Then, a few of you asked to have a meditation led on emptiness. I think rather then do that right now, because I want to give you some time to ask some questions… just a little tip here.

When some strong emotions come into your meditation, or you are remembering some past event, some memory, ask yourself, “Who is feeling this?” Or, if you find that you’re getting down on yourself, and beating yourself up, falling into self-hatred or self-pity, “Who is hating who? [chuckles]. Who’s the one doing the hating and who is the one that I am hating or putting down or whatever?” If you are finding that you are having a lot of attachment come up, you know, you’re missing somebody, or whatever; ask yourself, “Who is this person that I am missing? Who?” Ok, so first the name comes up. I shouldn’t mention any names should I?

R: P [name of husband of one R]! [laughter].

VTC: I miss P.… P.… did you hear that? [laughs]. Then C. and S. are going to get very jealous that I don’t miss them.

R: You’re missing them too…?

VTC: Oh… yes of course. [laughter]. Who do you miss the most?

R: Not C. [continues laughter]

VTC: So you can really sympathize? You can get together and talk about how wonderful C…

R: It will be P, tomorrow. I will wonder, why am I missing P—[not her partner]—Who is the person I am missing? Why am I missing him? [group laughter]

VTC: You can imagine everyone else in the group going, “why am I missing S?” [Continuous laughter.] …It can be very interesting to look at. Because you say the name and… let’s pick out another name, ok?

R: J

VTC: Are you still missing J? I thought you got over that. He’s a slow learner. Ok, give me another name. [laughter].

R: Joe

VTC: Joe, ok an innocuous name; but now Mary down the road is going to ask me why are you missing Joe? [laughter] Yes, there is Joe down the road. Ok, our mind has this image of this real person. You say the name, you know, “Joe.” And this person comes, Technicolor—right in your mind. You know, Joe, C, or J, P, or S—whoever it is, they come into your mind. And then they look so real don’t they? Ok, then just say to yourself, “But who are they?” You see their face so clearly, you know, who are they? Are they their face? …If there’s just this face there, is that the person I miss so much? …Yeah? …Is it some other part of their body that I miss so much? …So you can start looking through different parts of their body. You know. Look at the spleen, the liver, the intestines, the brain, the esophagus. Who are they? Who’s this person I miss so much. You start checking it out. Are they just the face? If they were just this face, this two dimensional face, is that the person you love so much that you miss, that you want to be with? This face? …Looking at you with the perfect look. You know you always have the look, the special look that they give to you and nobody else. [VTC makes a face] I don’t know what it is. [laughter] It’s been too many years.

R: S. still doesn’t know how to do that one. I’ve been trying to train him. [laughter].

VTC: You know you start looking at exactly who is this person? And then you start going to their mental qualities, because at a certain point you get past their body. No, they’re not their body. Because if their body is lying there dead, are you going to miss them so much? I mean imagine the person that you’re missing so much, imagine what they look like when they die. You know they’re laying out there—a dead body. Are you going to miss them? Are you going to want to hug and kiss them? You’re going to go “AHHeee!” [laughs] No, I’m scared. And I’m not talking about when they’re looking beautiful, just a dead body. So that’s how we get past their body.

Ok, so eventually we get past the body—but, what about their mind? You know? Ooh, who is it that I miss? Who are they? I want their ear consciousness that hears sound. That’s who I miss so much, their ear consciousness that hears sound. Do I miss their nose consciousness that smells? Do I miss their taste consciousness? Do I miss their tactile consciousness? Do I miss their eye consciousness, their visual consciousness that sees things? Oh, I miss their mental consciousness. Their mind! They have such a wonderful mind. Which mind do I miss—the mind when they’re sleeping? The mind when they’re angry? The mind when they’re spaced out? The mind when they’re full of competition—the mind when they’re loving? Which mind is it that I miss? Who is this person? And we begin to see that even the person’s mind or even what we call personality isn’t one solid thing—there are many, many, many different parts, and some of those parts are very contradictory, aren’t they? Do you miss their mental consciousness that is angry or do you miss the mental consciousness that has love and compassion? What about their mental consciousness that has love for the other women—do you miss that mental consciousness that has that love and compassion? No, we miss the mental consciousness that has love and compassion for ME! [laughs]. You know?

But you start going through and looking at who exactly is this person? Then you get to the mental consciousness that has love and compassion for me. So here’s this mental consciousness that has love and compassion for me… that is what I miss, a mental consciousness. [laughs] If only that mental consciousness were here right now… is that going to turn you on? [laughter]?

R: What does it look like?

VTC: That is the thing, it doesn’t look like anything does it? You know? Actually somebody told me about a ‘Star Trek’ program. I never watched ‘Star Trek,’ maybe once I think I watched it, but they told me about this program that they had, I forget who the characters are, but two people in a spaceship fell in love with one another. They were having this grand love. You know how in science fiction people can change their forms—get morphed out? Well initially this was a man and woman in love, but the woman got morphed out and returned as a man, same personality that she had before, now in a man’s body. Was he still in love with “her”? So, if the person you love that you miss so much were all of a sudden in different body, let’s say they came back with their same personality but they came back in their five year old body—are you going to miss them? Or maybe they come back in an eighty-five year old body—wrinkles, gray hair, saggy, shuffling along or sitting in an old folk’s home with a table holding them up, drooling. [Much laughter as someone says, that VTC has taken away all of their joy related to their partner.] Who exactly is this person that you’re missing?

Then you come to yourself—who is this person who’s missing them so much? “I’m missing them, I’m missing them.” Then you ask, “Who am I, who is this that’s doing the missing?” Who are you? So you start going through—go through your body, the different parts of your body; go through your mind, the different types of consciousness, different mental factors. “Who am I? Am I something different then the body and mind—this disembodied me with a personality, that is independent from anybody else, and that’s the one who is doing the missing? Am I the mind that’s missing them?” If I were the mind that’s missing them, then that’s all I would ever be, is the mind that’s missing them—but I don’t miss them every single moment of the day, do I? How much do you miss them, how often? Not really so often. Start investigating and ask—it can be very helpful. Or look at something that you’re very attached to, “I really have to have this”. What is it? What’s something you daydream about having, that distracts you in your meditation because you want it so bad? New curtains, a car, a computer, new clothes, what’s for lunch today—nobody ever thinks about what’s for lunch, do they? What is this lunch that I’m so attached to, what is this thing I want so much? And you start taking it apart.

We had pizza yesterday—it was very interesting—was it really pizza? Doesn’t ‘pizza’ always have tomato sauce and it didn’t have tomato sauce, so was it really pizza, or should we give it some other name? When I saw the crust I immediately thought ‘pizza’—“Oh, I like pizza! But it doesn’t have tomato sauce—is it really pizza, maybe it’s not?” Well, what is it that makes it pizza? Is it the white flour—no. Is it the tempeh—no. Which thing is it? Of all the different ingredients, which item is the pizza? Actually, maybe it’s not pizza because there’s no tomato sauce. What’s the definition of pizza? Whatever you’re attached to, break it up into parts and ask yourself, what is this thing that I want so much? Is it the collection of all the items? If they were all sitting out on the counter—would you go “Yum”? No, who wants to eat raw, uncooked tempeh, or white flour. You begin to see that it’s not the individual items, it’s not the collection of the items. What is it? It’s a bunch of things arranged in a certain way, and in dependence on that, my mind gives it the label pizza. All a pizza is, is a label what my mind has given in dependence upon all the things that form the basis of the label.

It’s just like being with the person that you miss—Joe: you’ve got the body, you’ve got the mind, all these different parts of the body, all these different parts of the mind, you give it a label ‘Joe’—that’s all Joe is. It’s just that label that’s given in dependence on the body and mind—there’s nothing more in there. This is such a good one for people when you’re attached to somebody or upset with somebody—you say their name and you’re ready to attack them or to hug and kiss them. Then you go, “Who are they?” Joe is just a label in dependence on that body and mind, that’s all. There’s no special thing that’s a real person, just a body and all these kind of consciousnesses; all the kind of consciousnesses, all these kind of mental factors—that’s all, all those different body parts. Then we can do the same for ourself, when we’re getting attached to some object, start asking, “What exactly is that object?”

When you’re first looking at it like there’s a real thing there—when you analyze it, you can’t find something. That doesn’t mean there’s nothing, it means your lunch exists; but lunch is the term that is given in dependence upon all of these different dishes, it’s nothing more then that. The verses that you’re chanting every other day about emptiness and dependent arising—this is what we’re getting at. Things arise in dependence upon causes, conditions, parts, bases of label and the mind that conceives and labels them. It’s not that they’re non-existent. They exist dependent on these things. But when you search for something that really is ‘it’ something really to get attached to, something to really get upset with, you can’t find the thing that’s ‘it’. When you think of somebody who harmed you, who did such a horrible, mean thing to you—which coincidentally sometimes is the person that you’re missing the most—who are the people that we’re the meanest to—the people we love the most or the people we don’t know? Who are the people that we get the angriest at, or who are the people who hurt us the most? The people we’re attached to. Often the real person that you’re attached to is also the one that you’re meditating on when anger comes. If we look from our side, we are the meanest to the people that we are most attached to. Because when we have so much attachment, so much expectation, then our anger and our jealousy, our meanness comes out against those people too. Similarly, sometimes the person that we’re very attached to has also been person who has hurt our feelings the most.

R: It could be.

VTC: Yes, it could be. But often it’s the person who has hurt us most because they’re so attached to us; we’re so attached to them, when you have a lot of attachment in a relationship, it’s a setup for hurting each other. R: For example: when you are meditating and you reach out for him or for her, you think that it is an advantage to feel attachment, but the meditation’s purpose is to see the attachment as a disadvantage.

There are many points I’m trying to bring out. One point is seeing the disadvantages of your attachment and how your attachment also brings the anger. That is one point I’m trying to get across. Another point is that we think there is one person who is either very mean to us or very wonderful to us. Ok… but who is that person? It looks like one solid person. But, just think, if that has some kind of inherent essence, they can’t be both mean and wonderful. So, when you can see that a person can be nice to you sometimes, mean to you other times and sometimes, they cannot even think about you, then you realize that what this person is, is not some kind of concrete person that you can find. They are an accumulation of all these different thoughts, all these different parts of the body, and they just have the name, “C, P, S, or J, Joe or Harry or whoever it is. We give them some name, but there’s nobody there when you’re looking; when you really analyze and check. Ok?

But that doesn’t mean there is nobody there, that the person doesn’t exist. The person exists, but they don’t exist in the way that they appear to us. Yeah? So, they appear in a way that’s false. It’s kind of like when you watch Television. When you’re really watching Television, you have a lot emotions come up don’t you? You know you’re watching this movie or watching the news and you have so many fears; you like this and you don’t like that, and you get really involved in the story. But, if we step back and ask, why do we have so many emotions around this story—because at that moment we’re relating to the television as if there were real people inside that box. Aren’t we? You know when the murderer comes to stock somebody and we’re sitting there scared to bits—I’ve had that happen to me. I’m watching a movie and I’m shaking. Why? Because we’re relating to it as if there were real people inside that box—are there real people inside the box?

R: Yes! [laughter]

VTC: Wrong answer! [more laughter]. You know there’s no real person inside the box. It’s a false appearance isn’t it? False appearance; but we bought into it and so we get so emotional about it. We’re actually misapprehending things. Yeah, so let’s go back to the example. It looks like real people but there are no real people there. Ok? When we know that then we still watch the movie, but we don’t need to get scared and we don’t need to get attached and we don’t need to get so judgmental. Ok?

Similarly in regular life, the way we apprehend people and they way they appear—and not just people but also things—as if they are real, findable with some inherent essence there. But again, when we search we don’t find anything real there. There is an appearance. All these things exist—they exist as appearances. They exist as labels that our minds have given to embrace that kind of object. But if we think there is anymore then that, it is like thinking there are real people inside the television. Yeah… so things exist, they appear—but there’s nothing real in there that we can hold onto. And so therefore there’s nothing real in there to get attached to, or to get so upset about. And there’s no real “me,” you know, that has to be the one through which everything is getting filtered. Why does attachment arise? Because something is pleasant to “me.” Why does aversion arise? Because something is unpleasant to “me.” Ok, so then we see first that we have this idea of a very solid “me,” then self-centeredness arises—everything is interpreted in terms of how it relates to me. If it’s nice to me, it is good, if it is not nice to me, it is not good. Yeah? And this is relating to what we were talking about in the beginning.

Creating karma

If somebody says nice sweet words to us even though the person is totally insincere, they’re a great person! We like being around them. Somebody points out to us our faults or something we need to work on, unpleasant words—we don’t like them. Because we’re filtering everything through “me.” Yo, yo, yo [Spanish for I, I, I]! So, then all these emotional reactions come and then with these emotional reactions we create karma, don’t we? Yeah, we like something, then, “I got to get it!” And so we’re doing all sorts of things; some of them harmful to other people, some of them unethical, some of them illegal—all to get the things that please “me.” Then when something doesn’t please me, we have to reject it and again, we’ll do things that are harmful to that other person or object or illegal or whatever to get them away from “me.” Because we see them as inherently harmful; and so we create karma. The attachment creates karma, the hostility creates karma. Yeah. Karma is what influences the situations we find ourselves in. At the time of death what karma ripens is going to influence what we get reborn as.

So we create all sorts of karma. Yeah? And then we’re just stuck in samsara, because we have all of these experiences. You know we wind up getting another body, having another set of experiences, and then, our afflictions again react—I like these things and I don’t like those things. These things are pleasant, those things are unpleasant get them away. These things I like, grab them, everything for me. Those things I don’t like gather them and get them away.” Create more karma. And then when you begin to really think about it, this is the whole evolution of my existence. This is what it means being in samsara, and this is what I’ve been doing since beginningless time and what I’m going to keep doing if I don’t make any changes. Then when you think about that, the preciousness of having met the Dharma… becomes… I mean—unbelievable! Because the Dharma is the one thing, you know, that is going to get us out of this vicious cycle.

R: Venerable, this thing creating the karma is it real or is it an appearance?

VTC: The creator of the karma—like everything—exists by appearance. There is nothing that is inherently existent. Ok? Because if things had their own inherent nature, they couldn’t function, they couldn’t change. If things had their own inherent nature they would exist independently from other things. If you exist independently, then things can’t affect each other and they can’t change. If there is one solid thing that is “me,” if there’s a real “yo” in here, you know, the sorrow that is forever and ever “me…” then how come that “yo” can one day be happy and the next be miserable? It shouldn’t be able to change; because it is “me.” You know, one solid unchangeable, independent thing that is me. It shouldn’t be able to change; to be happy one day and miserable the next. Because if something changes, that means it is dependent upon causes and conditions. If something changes it means it has parts. You know? Something that changes and has parts is not independent—it’s dependent. And it also depends on the concept and label that is being put on it. So there is nothing that exists inherently. Nothing! Not the creator of the karma, not the good karma, not the result of the karma—it all exists by being merely labeled, it all exists dependently. That is why it functions.

So this can also be helpful to think about, because you’re purifying different negative actions, sometimes some negative action may appear to be this incredible super solid thing, you know? I lied to somebody, or I hurt somebody and it just becomes like this action is so solid. “How can I ever purify that? I was such a horrible person who did that.” But, then look at the action. You know? Take the action of telling somebody off; saying some mean, horrible cruel words to somebody, and we think, “How can I ever forgive myself?” But, what was the action of saying the mean, horrible cruel words? Which word was it? Who said this tirade? Which sentence was it that was the mean, horrible, cruel one? Which word was the cruel, horrible, unforgivable one? We look and there were just a bunch of words. Maybe it was my mind that was cruel and horrible. Which moment of mind was cruel and horrible? The first moment—the last moment—the moment in between? To come up with this whole action that I call “telling somebody off, or being mean to somebody—doesn’t it depend on many, many moments of mind? Many, many different words? Doesn’t it depend on all these different parts? And my mind putting those parts together in such a way that I call them the action of, “being mean and cruel”? So, we begin to see that these negative actions that we’re purifying also exist by being merely labeled. Again, it doesn’t mean they don’t exist—they do exist. We do them and experience the results of them, but they’re not concrete. And the person who did them is not concrete either.

R: I can really see… and this is the first time that I have ever gotten a sense of why the two extremes are taught… the danger of falling into the two extremes is real… when you dismantle that mis-perception we have of reality, there are moments when you say, well, there isn’t anything there, period. You can see where the nihilists went to.

VTC: Yes, and then you begin to see that the two extremes actually come to the same point, which is, it’s got to inherently exist and if it doesn’t inherently exist, then it doesn’t exist at all. So that’s the belief that those of the two extremes hold. It’s just that one side says it exists and the other side says it’s totally non-existent. And that’s why the middle path is not somewhere between them; the middle path is totally out of that; because the middle path says they exist, but they exist dependently; they’re empty but they appear and they function.

R: It is so difficult to get. My mind is like—when I read about it or listen to the tapes on the Heart Sutra that you did—it’s like if I got it, I’d be terrified. I have that same fear when I meditate on my death—that I’m going to die. It’s so scary, I just want to get away and my mind says, “No”. It’s too different from everything and every thought I’ve been taught before.

Accumulate merit

VTC: Our mind is so immersed in its present view, that the idea—and we build our whole life on this hallucination—and the idea that it is all a hallucination and that everything we’ve been putting our energy into is a total hallucination—it’s scary to your ego, isn’t it? So it is very important to remember that it’s your ego mind getting scared, it is not wisdom mind that is getting scared. And this also shows us why it is important to accumulate a lot of positive potential or a lot of merit, because when we’ve accumulated a lot of positive potential, that acts as a basis so we don’t get quite so frightened. We might get frightened, but we’re able to bear the fear because we know that even though it is a fearful way of approaching reality; that reality is going to eliminate our suffering. So, even though it might be scary, we go towards it because we know that that’s the thing that in the end is going to bring happiness. It is like when you have cancer, you know, the doctor says you have to go in for this horrible surgery and it takes out half your insides, but you go because you know it is the thing that is going save your life.

R: But how does merit do that? How does it create that basis?

VTC: It… it does it somehow. [laughter]

R: Is it like our great, great, great Grandma? (referring to the teaching Khensur Rinpoche gave in which he noted that we do not know our great, great, great Grandma, but she had to exist—for us to exist.) [laughter].

R: Except that I think we have mixed feelings about this topic with time. The longer we keep precepts, the longer we practice, the longer we put our minds to gaining merit, there is some shift. And as you start to give up some of the things you’re clinging to, and you gain some confidence in the teachings—that is based on your own experience—then, that is all linked up with the merit; that is what merit of positive potential means. It acts as a firm base to stand on. To accumulate merit we start chipping away at some of our old belief systems, don’t we?

VTC: But to create positive potential by making offerings, we’re chipping away at ego’s belief system that says, “if I give it, then I won’t have it. I should just keep everything best for myself.” Ok? So the practices we do create positive potential and are chipping away at that ego structure in a very threatening way [slight laughter]. But we get used to that and it becomes easy. So then we begin to have more faith in the Dharma of emptiness, because also as we practice more we begin to hear more teachings and we think about the teachings.

So at first when we think about them we’re just trying to understand the words—“what’s this inherent existence? I’ve never heard that before.” Yeah? “Object of negation—why don’t they talk English?” [laughter]. Then, you get the words, you get the vocabulary, then you’re just trying to understand the concepts. “What does that word really mean? Ok I got! Object of negation, I can say it and it is English, but what does it really mean?” Then you’re just trying to get the concepts. This is all at the intellectual level, so it takes a lot at the beginning—just this. Then, after a while you begin to say, “Object of negation, Ooooh, that’s talking about what I see. Oh! It’s not just this concept in a book. Object of negation is what I see when I open my eyes. Object of negation is what I feel when I’m happy or unhappy—the truly existent “I”—Oh. Oh!” You know, so you begin to notice that. But you still forget it. I mean as soon as anything nice comes—boy that’s out the window isn’t it? [laughter]. “Object of negation is grasping at that truly existent object—not just anything. [laughter]. I want this!” Ok?

But then slowly with more familiarization you start to catch it. You can’t control it, but you still keep meditating; trying to understand this. “What does this mean dependent arising? And emptiness—what kind of words are these? Dependent arising, emptiness, yeah my mind is empty, my stomach is empty and my bank account’s empty. [laughter]. What is she talking about emptiness—I know emptiness. [VTC laughs]. What’s this thing about emptiness and dependent arising coming to the same point?” You know? “What does that mean? They’re contradictory. Emptiness is empty. Dependent arising is there… don’t tell me it’s not [tape unintelligible]… it sounds like George Bush. You just have to work with it for awhile. [Laughter—for a long while]. Start with looking for the inherent ‘I’—the inherent S

R: Well, now you’ve ruined everything! [laughter].

Apply antidotes

R: The other thing is with the positive potential, I think it’s the first time that I’ve ever considered how important the antidotes are. That’s the positive potential that we accumulate—this keeps flashing in my mind—that handout that Barbara gave us on antidotes—for jealousy, for pride… then I look and I say let’s try it, let’s see what this feels like in my mind instead of having this pride or competition around someone. What are the disadvantages of pride… what are the advantages of rejoicing in other’s good qualities? What does that feel like in my mind—instead of the habituation of being competitive and jealous? I never ever used the antidotes… I just complained in my mind all the time—and wondered why those thoughts never went away.

VTC: Think—affliction comes and we sit there, overwhelmed—hey, I’ve listened to the Dharma—but never think to apply the antidotes.

R: It’s the positive potential, right?

VTC: Yes, that’s what creates it… the positive potential is the prime antidote. You can see it is the advantage of doing retreat, the way it deepens your practice in a way that just doing a daily practice doesn’t necessarily do. Once you have a retreat experience, then you… … because to go through three months, you have to apply the antidotes somewhere along the line. Otherwise, you would get up and run away. You have to start practicing; and when you start practicing in the retreat you remember some of that later. And afterwards your practice becomes much richer because you have some experience in applying the antidotes.

You have more confidence, “I made it through three months without running away and hitchhiking home down Country Lane, where one car every hour comes by”. Some retreats are done in four sessions, some are done in six. I set up the schedule so that you would have little breaks between sessions but a break between sessions doesn’t mean you forget what you did in the previous session, you still try to keep your mind focused as to what went on. So when you start the next session, you can pick up where you left off before. You don’t have to do the sadhana slowly every session. In the morning you set your motivation, you might do the sadhana more slowly. Or if your mind is completely distracted you might do the sadhana more slowly. You can also do the sadhana more quickly. There’s an advantage to be able to do it slowly and there’s an advantage to be able to do it quickly too—sometimes you can concentrate better if you do it quickly; the sadhana is not that long. When you send out the light to invoke all the Vajrasattvas from all the Pure Lands you don’t need to think of each one, or you’ll never get through the session. At this point in the retreat, try and focus more on the mantra! You do want to accumulate 100,000 mantras in the retreat. Now that you are familiar with the sadhana, you have the steps down, so it’s easier to get the feeling from it, so you can spend more time with the mantra.

R: What if we don’t get to that number by the end of the retreat?

VTC: You have to stay here! [laughter]. They advise finishing it on one seat [cushion]. If you absolutely can’t stay on and finish it, you could take it home and finish there—but it’s good to try and finish here. Or I guess you can just stay on. You’ll still be here for the retreat next year [laughter].

R: Lama Yeshe was saying that he wanted his students to do at least one of these in a lifetime and I’m thinking that it would be great to do one every four or five years, to make sure the karmic load is kept in balance—it’s so powerful. Just having Barb in the space with us—what was it, five or six years ago that she did the retreat—and you can still see how it affected her practice. She really holds the space—she’s right there with us. I have to think some of that came from that retreat. She continued the momentum, she sustained something; a number of people from that retreat sustained something afterwards. Once in a lifetime is great, but more than once in a lifetime seems better.

VTC: Let’s dedicate! [Dedication of Merit]

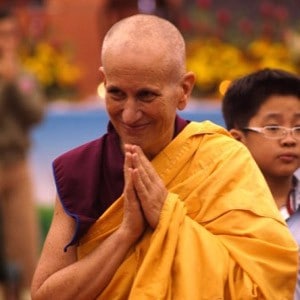

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.