Amitabha practice: Refuge and bodhicitta

Amitabha practice: Refuge and bodhicitta

Part of a series of short commentaries on the Amitabha sadhana given in preparation for the Amitabha Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2017-2018.

- Introduction to the Amitabha sadhana

- What it means to take refuge in the Three Jewels

- Why the Dharma is the real refuge

- Keeping in mind our long-term goal of becoming buddhas in order to benefit all living beings

This winter we’re doing the retreat on Amitabha, so I thought I would do a series of BBC talks about the Amitabha practice in preparation for doing the retreat this winter, because I think a number of people will be doing the retreat-from-afar. So we’ll put it on the BBC and that way everybody can hear it.

The Amitabha sadhana begins—as all sadhanas (the manual of the practice texts) do—with taking refuge and generating bodhicitta.

Refuge is stating at the beginning to ourselves what path we’re following. Why do we take refuge? So we get clear what spiritual path we’re following. We’re not: “Monday night I do Sufi dancing, and Tuesday night I do Kabbalah, and Wednesday night Buddhism, and Thursday night chanting Hare Krishna, and Friday night Jehovah’s Witness….” Like that. We’re really clear on what path we’re following, so we take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

The actual refuge, of the Three Jewels, is the Dharma refuge. The Dharma refuge means the last two of the four truths: true cessation and true path. The true paths are the wisdom consciousnesses that will help us overcome all our afflictions: ignorance, anger, attachment, pride, jealousy, and so on. The true cessations are the absences, the lack, of these afflictions on our mindstream as well as the emptiness of the purified mind.

The reason that this Dharma refuge of true cessations and true paths is said to be the actual refuge is because when we actualize it ourselves then our mind is free of afflictions, and as a result all of our dukkha (our suffering, our unsatisfactory experiences) cease. That’s what we really want to actualize.

The Buddha is the one that we see as the teacher. He didn’t make up the Dharma, he just explained it from his own experience, so we see him as the teacher. And then the Sangha as the people who have realized the nature of reality directly, non-conceptually, themselves. They have the actual experience of the nature of reality–of the emptiness of true existence.

We take refuge in these three because they’re all beyond the way of our ordinary, afflicted minds. Here what we’re doing is we’re taking refuge in the outer Three Jewels: the Buddha who already lived (actually, all the buddhas), the Dharma in their mindstreams, the Sangha, the people who have realized it. And our goal is by practicing the path that’s set out under the guidance of the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, that we will transform our own mind into the Dharma refuge. We will become the Sangha jewel and then, later on, the Buddha jewel.

The whole idea is, we’re not taking refuge in the outer Three Jewels thinking the Buddha’s going to swoop down and save us, and that all we have to do is pray and then Buddha does the work, and then we’re going to be liberated because the Buddha will take us someplace called Nirvana. It’s not like that. Nirvana is a mental state. The outer Three Jewels teach us that path to get to that mental state. We have to practice it ourselves. When we’re taking refuge we rely on the external Three Jewels in order to become the internal Three Jewels ourselves.

This is very important to understand, otherwise it’s really easy to bring in—if you’ve been brought up in a theistic religion—to bring that idea into Buddhism and think that we are taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha as external beings, and that they’re going to rescue us and take us to some place three clouds up and two to the right called Nirvana. It’s not like that. Buddhism is very much a path where we have to do the work ourselves.

This is good, isn’t it? If we’re the ones responsible then there’s the chance to actually make progress. If our liberation depended on propitiating some external being we could never control whether we get liberated or not because we can’t control that external being. The only thing we can possibly control is our own bananas mind. That’s why this whole path comes back to looking at ourselves and owning our own stuff. Instead of always “it’s outside, other people have to change, they’re doing this and that to me, and Buddha’s going to save me.” It doesn’t work that way.

We take refuge in that way and then we generate bodhicitta–the second part of the first verse, which is the usual one:

I take refuge until I am enlightened

in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

By the merit I create by practicing generosity

and the other far-reaching practices

may I attain buddhahood in order

to benefit all sentient beings.

Whenever I have to recite something alone that I have memorized I mess it up.

Bodhicitta is the second part of that. While refuge is making clear to ourselves what spiritual path we’re following, bodhicitta is making clear to ourselves why we are following that path. What are we doing, and why are we doing it?

Why are we doing it? Here our ultimate, long-term motivation is to become fully awakened buddhas so that we’ll have the capacity to benefit all living beings. That’s a very noble, fantastic motivation. It’s a long way out there, isn’t it? It’s going to take us creating multiple causes and conditions to attain that state. So we have to go step by step. But it’s kind of like, if you want to get to Dharamsala, first you have to get to Spokane, then you have to get to Tokyo, then you have to get to Delhi, and then you have to get to Dharamsala. You take it in little chunks. Similar for us, when we practice the path we take it in chunks. We start out with ethical conduct, we progress to concentration, then we progress to wisdom. Or another way of formulating it: we start with generosity, then ethical conduct, fortitude, joyous effort, meditative stability, then wisdom. There are many different ways to outline how we do this. There are also the three principal aspects of the path, there’s the lamrim (the three capacities of beings), many different ways. If you look in “Approaching the Buddhist Path”, volume one of “Wisdom and Compassion” there’s a whole chapter about the different ways to approach.

The idea is we’re all going towards full awakening motivated with love and compassion, and right now our love and compassion is kind of theoretical. Isn’t it? “I have equal love and compassion for everybody as long as I’m sitting here and they’re not bugging me.” As soon as somebody bugs me my love and compassion are out the window. Somebody says something I don’t like–POW–I’ve got to set this person straight. They can’t talk to me that way, they can’t do this. For their own good I’m going to punch them in the nose so they’ll get a taste of their own medicine and they’ll correct themselves. That is our afflicted mind, isn’t it? What we’ve done our whole lifetime. And where’s it gotten us? Nowhere.

When we generate bodhicitta we’re committing to ourselves that we’re going to try and change a lot of our adverse emotional habits. This takes time. It takes willingness to do it, to practice. To sometimes fall down. We’re trying hard and sometimes we blow it. But to pick ourselves up every time we blow it and keep going. Because what’s the alternative? There’s no other good alternative but to practice.

We keep generating love and compassion as much as we can. We keep watching ourselves not meet our own expectations. We come back to the cushion, we try and penetrate what’s going on inside: Why am I upset? Why am I angry? Why am I fearful? Regenerate love and compassion. Go out again, keep trying. We do this on the cushion, we do it off the cushion. This is why this verse of taking refuge and generating bodhicitta we do at the beginning of every single practice that we do, because we repeatedly need to say to ourselves, “I am following the Buddha’s methods because I want to get to full awakening for the benefit of all beings. I’m committed to that and, slowly slowly, I have to accept my own abilities, I have to accept that other people are also trying as hard as they can and they’re going to fall down just like I fall down, but all of us, in our minds, are trying to go in that direction. I’m going to train my mind to see other people in that kind of light instead of my old habit of seeing other people as threats.”

It’s a big practice for all of us. Isn’t it? This is why we say it at the beginning of the practice, so that we’re clear in our minds: “This is why we’re doing the Amitabha practice.” We’re not doing the Amitabha practice because we can visualize the pure land and that makes us feel so good, like we’re in Disneyland. That’s not why we’re doing it. We’re doing it because we’re willing to engage in the hard work of transforming ourselves, because we see that that’s the most worthwhile thing we can do in our lives. Even if it’s difficult. Doesn’t matter. We keep doing it.

That’s the first verse of the sadhana.

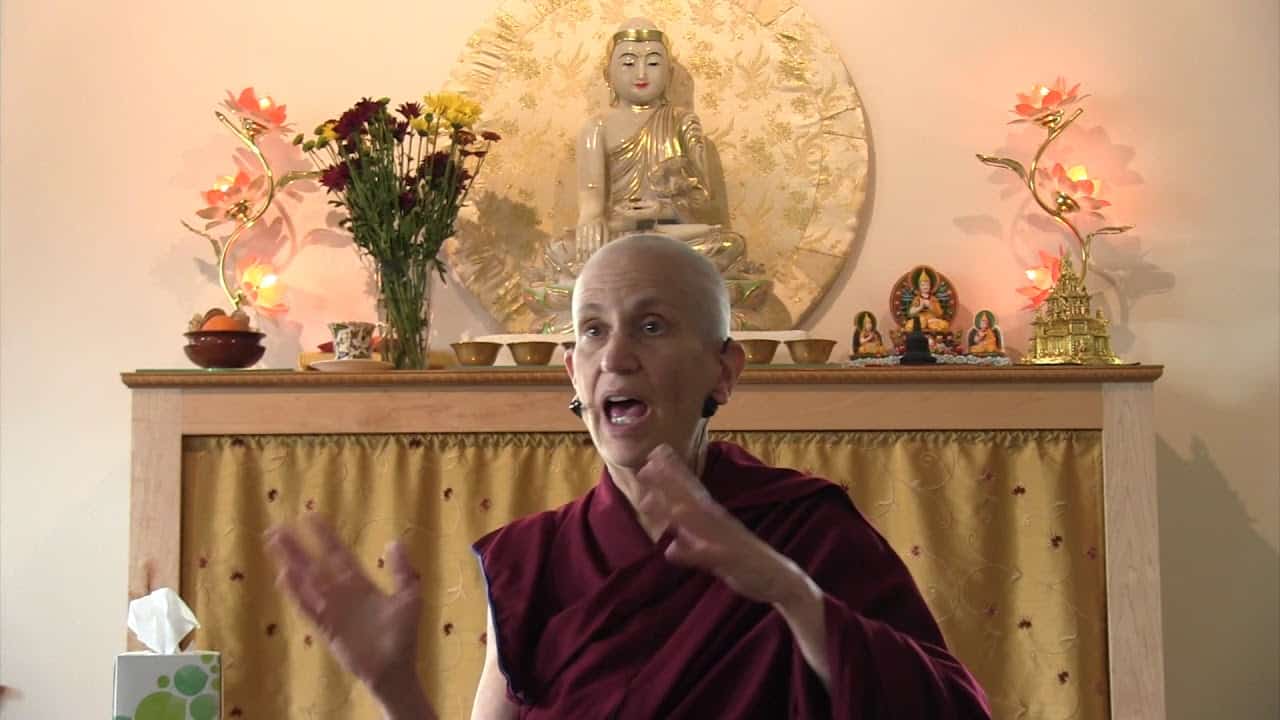

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.