The second noble truth: the root afflictions

The second noble truth: the root afflictions

Part of a series of teachings on The Easy Path to Travel to Omniscience, a lamrim text by Panchen Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen, the first Panchen Lama.

- The first five of the six root afflictions and how they cause dukkha

- Attachment and how it is related to fear

- Anger and the ways we justify our anger

- The eight types of conceit

- The different types and levels of ignorance

- Deluded doubt

Easy Path 24: The root afflictions (download)

Venerable Thubten Tarpa: Good evening everyone here and from afar. Venerable Chodron will be joining us in about 10 or 15 minutes. As we recite these prayers, I’ll go through the various visualizations very briefly.

[Recitation of prayers]

Although we have said these words of wanting to become a Buddha in order to help all sentient beings and we have that aspiration, we haven’t really got ourselves all the way there to be able to do that. Now we want to contemplate the four immeasurables and we’ll spend some time with this to help to bring our minds around to this vast motivation of bodhicitta. We will pause between each of the four verses, because it takes some time to contemplate. Make your mind into that sentiment.

[Recitation of prayers]

Take some time to let go of anything that’s keeping you from having that motivation.

[Recitation of prayers]

Let’s do the seven-limb prayer. We’ll go straight through and do the visualizations, contemplating each line as we say it.

[Recitation of prayers]

Then we’ll offer the mandala, wishing to offer everything in the universe in order to receive teachings and to generate realizations within our mindstream. We’ll do the short mandala offering and the mandala offering to request teachings on that page.

[Recitation of prayers]

We make requests to imagine that, from the Buddha in front of you, a replica of your teacher in the aspect of the Buddha comes to the crown of your head facing the same direction as you and as we make this request, imagine the Buddha on the crown of your head acting as an advocate for you.

[Recitation of prayer]

Now the Buddha in the space in front of you merges with the Buddha on the crown of your head. As we recite the Buddhist mantra, imagine this beautiful light and nectar flowing into you completely filling your body. You can imagine this on the heads of all sentient beings surrounding you as well. Start with the visualization.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): We are focusing on the Buddha on the crown of your head, and let’s make the following aspirations. Think: “the fact that I and all other sentient beings have been born in samsara and are endlessly subjected to various kinds of intense dukkha or unsatisfactory conditions is due to our failure to cultivate the three higher trainings correctly. Once we have developed the aspiration to liberation, Guru Buddha, please inspire me and all sentient beings so that we may cultivate the three higher trainings correctly.”

Then continue thinking: “mind on its own is by nature ethically neutral. In relation to the thoughts I and mine first arises the thought that they are inherently established. Then, on the basis of this mode of apprehension of the I, arise various kinds of wrong thinking, such as attachment to what is on my side, anger towards what is on the other side, arrogance that deems me superior to others. Then on that basis arise doubt and wrong views that deny the existence of the guide the Buddha, who taught selflessness, and of his teaching karma and its effects, the four noble truths, the Three Jewels and the like. And then, based on these other afflictions, we accumulate karma under their influence. And by this we are obliged to experience a wide variety of dukkha in cyclic existence. Therefore, ultimately, the root of all Dukkha is ignorance.

May I by all means attain Guru Buddhahood that frees me from the root of all of samsara’s suffering. For that purpose, may I correctly train in the qualities that are the three precious higher trainings. In particular, may we correctly guard the ethical discipline to which I have committed myself even at the cost my life, since guiding them as beneficial, and failing to do so, is extremely harmful.”

In response to your request to the Guru Buddha to inspire your mind to gain these realizations, five-colored light and nectar stream from other parts of his body into you, through the crown of your head. Light and nectar absorb into your body and mind. Then think that the light from the Buddha in front of you radiates also to all the sentient beings around you. And this light and nectar flows into their body and mind.

As the light and nectar enter us it purifies all negativities and obscurations accumulated since beginningless time. Especially, it purifies illnesses, interferences, negativities, and obscurations that interfere with cultivating the three higher trainings correctly once we have developed the aspiration to liberation, so think that all of that is purified and feel what it’s like to be free of those obscurations. Your body becomes translucent, the nature of light, and all your good qualities, lifespan, merit and so forth, expand and increase. Having developed the aspiration to liberation, think that the superior realization of the correct cultivation of the three higher trainings has arisen in your mindstream and the mindstream of others.

Last week we were discussing the practice of the middle level of beings, people who aspire for liberation from cyclic existence. They already want a good rebirth and samsara, but they know that that’s not sufficient. They’re wanting to get off the merry-go-round of cyclic existence. To do that, first we have to cultivate renunciation, or the determination to be free. That’s done by contemplating the four truths seen by the noble ones or the arya beings.

Last week and the week before we talked about the first of the four truths, the one explaining dukkha, or unsatisfactory conditions. We talked about all the difficulties of being born in any of the realms in cyclic existence, because all of them come about due to ignorance. There’s nothing healthy or good that’s going to come out of ignorance.

Then the second truth goes into what is the cause of the origin of this kind of situation. First, the Buddha has us meditate on what is our situation and what are its causes so that we can see that clearly and then aspire to get out of the situation. That’s really important before we go on to thinking about nirvana and the path to nirvana, let alone full awakening. This week, we’re going go into the second truth, the origins, or the causes. That involves talking specifically about the afflictions. Yes, primarily, ignorance as the origin and then the other afflictions that come out of ignorance, and then the fact that through acting with these other afflictions, we create karma.

Then that karma is polluted by ignorance, and so it is what, immediately causes the rebirth, because at the time when we die, when the body and mind of one life are separating, then, due to craving and clinging, some karma ripens, and depending on what karma ripens, then our mind is propelled into a specific rebirth. And then once we’re born in that rebirth, then we’re back with aging, sickness, and death, and all the specific miseries of that particular realm of rebirth.

There’s a causal link here. It starts with ignorance, goes to afflictions, goes to polluted karma, goes to rebirth, and all of the attendant dukkha that arises. We have experiences we don’t like and we go, “why is this happening to me?” It happened because of my polluted karma, which arose due to my afflictions, which are based on my ignorance of the nature of things. Why am I having this problem? It’s not due to anybody else—it’s due to the pollution in my own mind. Therefore, I have to purify my mind. That’s also why we’re going to be doing Nyung Ne tomorrow. This particular topic fits in very well with the motivation for the Nyung Ne practice tomorrow.

So let’s go on and look at some of those different things. When we talk about affliction, sometimes it’s translated delusion or I used to call it disturbing emotions and disturbing attitudes. I think I have finally come to the conclusion that I think affliction is better, because we are afflicted by these mental attitudes. An affliction is defined as a phenomenon that, when it arises, is disturbing in character and that through arising disturbs the mindstream. It’s something that when it comes up, by nature, is disturbing, and it disturbs our mindstream to the extent that we then act out of it. Then, through our actions, we create karma. We also disturb the lives of other living beings.

Disturbance is the primary function of afflictions, and I think no good is going to come out of them. There are different lists of afflictions and different ways of categorizing them. One way of categorizing them is into the six root afflictions. They’re root because they’re the fundamental ones. Based on them, all the other auxiliary ones come out. These six: first, attachment, you know that one; anger, we know that one even better; conceit, got that one down pretty well; ignorance, we have that all the time and we’re not even aware of it; doubt; and afflictive views. Then, within afflictive views, there are five types that we’ll go into [later].

Those are the six root afflictions. Let’s look at each one. The first one is attachment. Attachment exaggerates the attractiveness of a contaminated or a polluted object. A polluted object is an object created in the samsaric environment due to the ignorance of all the beings who live there. It’s not a pure object, let’s say like the Buddha, or the realization of emptiness, or something like that. It’s something that exists due to the minds of sentient beings, either a natural thing, our environment, or something that we have created. It’s a new way of thinking—that your computer is polluted, and your iPhone is polluted, and you don’t like that—“no, my computer and iPhone are the basis of happiness.” No, not actually.

Attachment exaggerates the good qualities of this kind of object. Having exaggerated those good qualities, then it wants to hold on to the object or the person. When I say object, it doesn’t necessarily mean an inanimate thing, it could also mean a person. We want to hold on, and we see this thing or person as having happiness in it, and by associating with it, then we’ll have happiness. The happiness will go from the object into us, just like when you eat chocolate, right? The happiness is in the chocolate. Yes. When you eat it, the happiness comes into you. That’s the way we see it, isn’t it? Yes. Or you’re with a person you like, the happiness is inside that person.

When I’m with them, then it radiates out to me, and I get happy. Of course, things don’t always operate that way. There are different degrees and variations of attachment. People will have attachment to different objects, and clearly to different people. The way attachment operates is always the same. It’s based on exaggerating the good qualities or projecting good qualities that aren’t even there. Sometimes we do that too. There are absolutely no good qualities about the object of the person, but we project all these good qualities onto it, then cling and hold on.

This kind of attachment is the source of our dissatisfaction. Because with attachment, we want, we want what we don’t have, and we hold on to what we do have. It brings dissatisfaction because we can never get all we want, or whatever we want. Can you think of examples in your life where you wanted something, and you couldn’t get it and were dissatisfied? Yes. The source of the dissatisfaction is not the external condition that we can’t get what we want, the source of the dissatisfaction is the attachment that is clinging on to the object. Because when there’s no clinging, then there’s no sense of dissatisfaction. It’s only when the mind is clinging that we’re dissatisfied, because we want more, or we want better.

Attachment not only is the source of dissatisfaction, but it also gives rise to fear. Because once we have something, then we don’t want to lose it. Of course, because we can’t hold on to things forever, fear arises that we’re going to lose what we have that we really like. Or if we haven’t gotten it yet, fear comes that I won’t ever get it. It’s quite interesting how the fear is related to attachment. “I got this, this is so wonderful, but maybe it’s going to get taken away from me, maybe this person doesn’t really love me, maybe they’re going to leave me, maybe this thing’s going to break, maybe somebody else will get something even better than what I have”. Fear and anxiety often arise due to the attachment. Then comes the dissatisfaction of not getting everything we want, which everybody suffers from.

Right off the bat, I think it’s very helpful to see these aspects of fear and dissatisfaction. Because we can identify those two mental states as unpleasant. Yes, and then say, “Oh, attachment must be behind it.” When only attachment is in our mind, sometimes we don’t identify it as an afflictive state of mind, because we feel good. “I got what I want. I’m happy. I got the promotion; I got the money. The person I really care about is with me, I’m lying on the beach in Hawaii in the middle of winter, oh, this is definitely happiness.” When we have that happiness, there’s often attachment to it. Therefore, we don’t see the attachment as something that’s afflictive, because often the feeling of happiness accompanies that. The thing is, if we stay with that object long enough, the feeling of happiness goes, and the feeling of discomfort comes. You’re lying on that beach in the dead of winter. You’re lying on that beach, and you’re lying on the beach, and you’re lying on the beach. Eventually, you want to get out of that beach, don’t you? It’s like, “I’m fried on this beach. I’m tired of lying down. I want something else.” That’s called the dukkha of change—that what we call happiness is actually a state of discomfort, that’s still small. It takes some study of our mind, to be able to identify attachment, and then to be able to say: this is something that I want to eliminate.

Because as long as we’re getting what we want and we feel happy, our renunciation of cyclic existence is out the window. Yes, why renounce samsara if it feels so good. Attachment makes us feel good. How could it be an affliction? Then when we hear, “Oh, it’s an affliction,” then we misunderstand. We think, “Oh, Buddhism is saying you shouldn’t be happy.” Have I said that? In this whole discussion of the disadvantages of attachment? Did I say that means that it’s bad to be happy? No. That’s where our mind goes, “Oh, attachment is bad, happiness must be bad. Buddha doesn’t want us to be happy. We have to renounce and we’re renouncing happiness. Somehow, I’ve got to suffer. Through suffering, I will gain redemption.” Sorry, folks, that is your Christian background, that is not what the Buddha is saying.

It’s quite interesting, isn’t it? We have that in our culture, don’t we? You somehow have to suffer to atone, and the body is evil, and happiness is evil. You’ve got to beat your body and deny yourself? No, that’s not what the Buddha said. The Buddha said, look at your own mind. When you do you see that in the long-term attachment, and all of its varieties, craving, clinging, greed, possessiveness, you see that all of these things don’t bring you happiness, and they bring you suffering. Because we want to be happy, we want to be free of these things that, in the long term, bring us suffering. Because we want happiness, and it’s fine to have happiness.

Where our problem arises is when we cling to the happiness. We can’t just let the happiness be, it arises, it ceases. It arises, and we go “Oh,” and we hang on for dear life. Like this can’t go away. And that mind state that is suffering is that mind state that is greedy, that never feels satisfied. Whatever we have, we want more, we want better. We take advantage of other people, we’re self-centered, we take the best for ourselves, leave the non-best for somebody else. This whole mind of attachment really creates a lot of problems.

The Buddha is not saying don’t be happy, he’s saying be happy. Just don’t cling to the happiness because the clinging will make you unhappy. You can really see that in your life when you consciously practice not clinging, or not being greedy. When you really consciously practice it. Yes, then you couldn’t watch the happiness come, you are satisfied with what’s there. You know it’s going to go away. When it goes away, you’re okay about it. Whereas when we have attachment, the happiness comes, we hang on. “I can’t ever be separated from this never, ever, ever.” Of course, as soon as things come together, they are going to separate sometime, or they’re going to decline in happiness. Then we go, “Oh, woe is me. I’m so miserable. I’ve lost my happiness. How am I going to survive? Nobody else has ever been suffering like me.” This is part of the problem with attachment.

That’s the first one of the six. Now, when we can’t get what we’re attached to, or when what we’re attached to goes away, then how do we respond? Anger. Another by-product of attachment is anger and anger is the second of the root afflictions.

Similar to attachment, [which is] exaggerated and projected good qualities on someone or something and then clinging, anger exaggerates or projects bad qualities on someone or something, and then pushes away from it, or wants to destroy it. It’s a similar mechanism, but in the opposite direction. Our mind is very good at creating many reasons to justify our anger. We’re quite good at that. Any reasonable person would be angry at this person, “Look what they did, they did this and this and this, and this, I have every right to be angry.” My anger just says it’s an exaggeration of negative qualities. “No way, that’s not true. I’m seeing reality, the same way as when I’m attached to something, I’m not exaggerating good qualities, I’m seeing that person or that object as they really are, they are the best thing since sliced bread,” and then a few years later, they are the worst thing since. They invented sewers. Our mind is perpetually refusing to accept that we are exaggerating. Especially with anger, “I am not exaggerating, I am seeing reality. The situation is very simple. That person is wrong. I am right. The way to remedy is they need to change, very simple.” Isn’t that how we think when we’re angry? “I’m right, you’re wrong. The solution is you change. Because you’re wrong and I’m right. I’m not going to change. I’m not going to give in.” You see individuals do this, groups do it, nations do it.

We’re in a big mess because of it. There are nine reasons in particular that we often use to justify our anger. You can maybe make some examples for these in your life. When we’re doing Nyung Ne and when you can’t talk, you need something to think about. Yes, this is a real good thing. Think about this teaching. The nine things, what we think about. “This person harmed me in the past, therefore I’m furious.” Can you think of somebody right this instant? Only one, not ten. I bet, sure.

We can think of ten that fulfill this description. “They harmed me in the past.” That’s one. Second, “They’re harming me right now.” Third, “They’re going to harm me in the future. Gosh, I don’t know that but I’m certain they are.” It’s called paranoia, suspicion. Then the second set of three: “They harmed my dear friend or relative. In the past, they harmed them. The person who I cherish so much, somebody harmed them, that’s awful. Or they’re harming my dear friend or relative right now. Or they’re going to harm them in the future.” You’ve had all those thoughts? I bet you can think of a lot of examples like this.

Then the last set of three are, “They helped my enemy? People I don’t like people who threatened me. People who interfere with me getting what I want. They helped that idiot. Terrible. They deserve my anger. They helped my enemy. They are helping my enemy. They will help them in the future.”

Those are nine justifications for our anger. True, not true? True. It can be very helpful for us to sit down and write out examples of all these things so that we can begin to learn how to identify our afflictions. The next one is conceit. Some people translate this one as pride, or sometimes arrogance. But for me conceit has a particular flavor, because being proud like a parent who often says to their child, “I’m proud of you.” Pride can have that kind of good side. When they say I’m proud of you it means I rejoice in your good qualities. But conceit: you never heard that word said in a virtuous sense, do you? Does conceit have a special flavor to you? Proud. Yes, that’s not so good. Arrogant: that’s worse than being proud. Conceit: that person’s beyond the beyond if they’re conceited. In the sixth grade somebody said I was conceited.

You see, this is what 58 years ago. No, how old was I in sixth grade anyway. How many years later, and somebody said I was conceited. “How dare they say I’m conceited. Just because I’m better than they are.” Yes. We often have a hard time; I can see two.

There are different kinds of conceit. Here there are seven kinds. The lists are very good. There’s the conceit of thinking, I am superior in relation to somebody who’s inferior. Here and in the next two kinds of conceit, also those first three, we’re comparing ourselves to others, based on maybe our wealth, or the kinds of possessions we have. “I have a nicer car than they do.” “I’m more attractive,” smirking, “you have the same hairdo. Mine looks better than yours.”

We get conceited over our knowledge; our social standing, “Oh, I have a higher social standing. I’m from a better family a better socio-economic group;” we get conceited over our athletic ability; over fame; over our musical abilities, or artistic abilities. We even get conceited if the cat lets us pet her more than she lets other people pet her. That is a cause for superior social standing. Good luck. We are always involved with comparing ourselves to others.

This comparison with others is, I think, one of the worst things we do. Because when we compare ourselves with others, we come out conceited because we think we’re better. Or we come out jealous because we think we’re worse. Or we come out competing because we think we’re equal. None of this comparison when people have an afflictive mind brings about cooperation. Yes, and really, it’s cooperation that is going to make us happy. It’s not survival of the fittest. It’s survival of the most cooperative.

Interesting, spend a little time thinking, “What areas of my life do I compare myself to somebody who’s inferior—they don’t know as much as I do, or they aren’t as good looking or as talented or whatever as I am.” It’s the conceit thinking, “I am superior.”

The second one is the conceit thinking I am superior in relation to somebody who’s equal. In the first one, we were, in fact, better than the other person, and we’re conceited about it. In this one, we’re equal to the person, but we still think we’re better.

The third one is conceit thinking, “I am superior in relationship to somebody who’s better than me.” That happens too. Doesn’t it? We so much want to be good or the best that we will put down somebody who’s better than us so that we can come out looking good in our own eyes.

The fourth type of conceit is conceit with regards to the aggregates or with regards to the self. This is the conceit of I am. I love that terminology, that conceit I am, because just the thought I am, when we are grasping onto inherent existence, reifying this I, making it something that it isn’t, is a form of conceit, isn’t it? It’s building it up to be something it isn’t. It’s just the conceit saying, “I am, I exist in this universe, I am a presence, you have to deal with me.” It is the conceit of I am.

Based on self-grasping, we flaunt ourselves as important simply because we exist. It is the conceit I am. Yes, “I am, you cannot ignore me. I am going to yell and kick and scream and shout and cry until you pay attention to me. Or if you still don’t, then I’m going to go shoot somebody or beat somebody up, or I’m going to go in my room and cry, or I’m going to do something until you recognize that I am and that I am a force that you have to deal with.” Yes, but the best is,” If you think I’m wonderful, then I don’t have to do the tantrums to prove that I exist”.

Oh, I didn’t do all of the forms, those are only four forms of conceit. The fifth one is conceit that we have good qualities that we don’t have. We’re kind of average about something, but we think we’re really good. Or we might have something a little bit better than what somebody else has but it’s really not spectacular. Again, we inflate it and think, that “I have good qualities that other people don’t have: I know how to wash the dishes in the Abbey so that the inspector will pass us, and you flunk when it comes to washing dishes. Yes, I’m a failure. I dare not wash a dish in the kitchen because I’ll do it wrong. Other people are better than me. They let me know it too. Get out of here. Go give a Dharma teaching or something, get out. You don’t know how to wash dishes worth beans”. Conceit thinking that we have good qualities that we don’t have.

The sixth one, this is a very interesting one, is the conceit thinking that we’re just a little bit inferior to somebody who’s really wonderful. “In this group of esteemed persons, I am the least qualified.” Yes, you know that one? “Of all the people who got to sit on the stage with His holiness, at His teachings in New York, I’m the one who least deserved it”. But you noticed I sat on the stage, didn’t you? Yes. This is the conceit that implies that although we are less than those who are world-renowned experts, we’re definitely better than the majority of nincompoops. “I’m not nearly as good a swimmer as Michael Phelps,” implying, “But I’m getting there.”

Then the seventh is the conceit thinking our faults are virtues. This is a really horrible kind of conceit. For example, somebody who is ethically degenerate thinks that they’re upstanding and righteous. This is Wall Street, isn’t it? Yes. This is politicians, people, none of those people think, “Oh, I’m morally degenerate.” They all think “I’m morally upstanding, I’m upstanding, that’s why the people voted for me, that’s why I got as high as I did, because I’m morally upstanding,” and they can’t see their faults or see their nonvirtues. That kind of conceit is really bad because then we’re going to continue to create a lot of nonvirtue, and we’ll never even be able to recognize it so we can’t purify it.

We can never be free of it if we can’t purify it. It’s the conceit that says, “I closed the business deal with that guy, and he didn’t even know that I charged an extra 1 percent.” Or, whatever we do, sometimes when we’re making deals with people, it’s like, “I talked them into buying this thing that they don’t really need, but I made them think that they needed it. Now I get a big commission. I’m fantastic. What a great salesperson I am.” Actually, morally, that’s not very good, is it, to talk somebody into buying something they don’t need then they’re going to sweat to have to pay off. You pat yourself on the back, “Look, what a good salesman I am.” That’s another kind of conceit, thinking our faults are virtues. You know what it’s like.

Also, some people take real pride in being rebellious. It’s like, “I’ve got to be rebellious for the sake of being rebellious”. Then I can say, “Look at me, I don’t go along with the crowd.” The way we’re rebellious sometimes is in quite obnoxious ways that are really not very pleasant to other people. We take great pride in being rebellious in that way. It’s like the pride we took when we were teenagers, when we could talk our parents into giving us what we wanted, or the pride we took when we were able to make our parents think we were in the house when actually we had snuck out. Or whatever it is, we’ve done something that’s not very good, and we take immense pride in it. That’s a form of conceit. The sixth kind of conceit, here, it’s listed as thinking we’re just a little bit inferior to somebody who’s really wonderful. In other lists of the seven kinds of conceit, this is the conceit that thinks I’m the worst of everybody.

This is the conceit of “If I’m not going to be the best, I’m the worst. Yes, I can screw this up. I screwed that up. I can make a mess of anything; I do everything wrong.” This is the conceit of guilt and self-loathing. I bet we never thought of self-loathing as a form of conceit. It is, isn’t it, because it puts undue emphasis on the self? “I am so powerful; I can make it all go wrong. That’s how powerful I am. Of course, I hate myself because I made it all go wrong. I only have myself to blame. I always do that.” So it’s this reverse kind of conceit.

Conceit: one of the disadvantages, I suppose you can see many already, one of them is when we’re conceited, we become invincible to learning anything. Because when you already know everything, then you can’t learn anything from anybody. Every time somebody offers us some suggestions, we say, I know, I know. I know. I know, before the person’s even said it. We make it very hard to learn anything because we’re always, “I’m very good already. Don’t tell me how to do anything.”

Shall we go on to the next one? What’s your favorite so far? Attachment, anger, or conceit? Then the fourth one is ignorance. There are many, many different types of ignorance. The term can refer to slightly different things, or sometimes very different things in different contexts.

In general, we say there are two kinds of ignorance, the ignorance of the ultimate truth, in other words, the ignorance of the ultimate mode of existence of phenomena. Then the second is ignorance of the conventional truth, which is principally ignorance of karma and its effects. The ignorance of the ultimate truth is what grasps at people and things as existing inherently from their own side. It misapprehends them. The ignorance of karma and its effects is just our total confusion in what to practice and what to abandon, what is virtuous and what is not virtuous. “What should I do and what should I stop doing if I want to be happy?” Now, sometimes when we talk about the ignorance of the ultimate truth, each religion is going to have a different definition of ignorance, what it says that we are ignorant of. But even within Buddhism, there are two views about this ignorance of the ultimate nature. One is that ignorance is just like a smoke screen. You can’t see the ultimate truth clearly. It’s a non-knowing, it’s obscuration. It’s a not knowing of something. There are other schools that say, it’s not just a not knowing it’s an active misapprehension of how things exist. This is a big difference.

One is just, “Well, I don’t know the nature of reality.” The other is, “I grasp at things existing in the exact opposite to the way they actually exist.” It’s an active misapprehension. For example, the sautrāntikas they say or, and even the Sangha, in the chittamatra, he’ll say ignorance is just this obscuration of not knowing. According to the prasangikas, ignorance is actively grasping at ourselves and all phenomena to exist in a way that we don’t. You can see even within Buddhism in the different philosophical schools, there are going to be different definitions of ignorance. Especially regarding the self, some philosophical schools within Buddhism say, “Oh, we think that there’s a permanent partless independent person.” That’s the wrong idea that we have, we’re just plain old, obscured, we don’t see that there’s no permanent partless, independent person, or soul, or self with a capital S. This is a very gross kind of grasping, thinking that there’s a permanent soul. Because this is something that is taught to us—it’s not an innate kind of grasping, we learn it. When we’re kids, don’t we, we learn it, that you have a soul. “What’s a soul”? Then they tell you. That’s one level, then beyond that, it’s the ignorance thinking that there is a self-sufficient substantially existent person. This is like the ignorance that thinks of the self, the I as a controller. “I’m in control of my body and mind. I make decisions around here.” We have that feeling, don’t we? But when we search for the controller of the body in mind, we can’t really find anything. There’s ignorance in that we think that there’s some kind of self that is in charge.

Then last is the ignorance thinking of the self or the person as something totally independent of everything else. Yes, so it doesn’t depend on parts, it doesn’t depend on causes and conditions, it doesn’t depend even on being conceived and given a name. The truly inherently existent self.

There are different levels of ignorance, even regarding the self, the person, what we’re obscured from seeing or what we are actively grasping at. Then there’s the ignorance that is the mental factor. That’s the obscuration or unknowing about the four truths of the aryas, or ignorance of the Three Jewels, ignorance of the law of cause and effect, ignorance that is a mental factor. There’s ignorance that is one of the three poisons, we say the three poisonous attitudes—ignorance, anger, and attachment. There, ignorance means specifically, ignorance regarding the law of karma and its effects. Sometimes, instead of ignorance, we call that confusion, although at other times, that term confusion also refers to self-grasping. Then there’s the ignorance that is the first link of dependent origination, the 12 links. That’s the ignorance that grasps at a truly existent self, that gives, from the prasangika viewpoint, that gives rise to afflictions and then leads to karma. That’s ignorance. That one is the source of the whole thing because it’s a fundamental obscuration and misunderstanding.

Then fifth is deluded doubt. There are three kinds of doubt, and this is one of them. There’s one kind of doubt that’s inclined towards the correct conclusion. One that is in the middle, and one that is deluded inclined towards the incorrect conclusion. An example of doubt inclined towards the right conclusion is, “I’m not sure about rebirth, but it kind of makes sense.” Then in the middle is, “I’m not sure about rebirth, I could go either way on it.” Then the deluded doubt is, “I really don’t think there’s rebirth. Yes, I’m pretty sure that whole thing’s a bunch of baloney.” If you really feed your deluded doubt, then it’s going to go all the way to wrong view. Like, “Oh, rebirth is just a bunch of garbage, and somebody made it up in order to scare people.” We get really cynical about the whole thing. Deluded doubt. Here, it isn’t the doubt, like, “Well, should I vote for this party or that party”? Yes. Or the doubt of, “Well, what’s the cause of all the bees dying, it could be this or it could be that?” This is the kind of doubt that is in relationship to important things in terms of your spiritual practice.

Then the sixth one is afflictive views. There are five kinds of afflictive views. Maybe before I go on to that, let’s see if you have any questions or comments so far. Otherwise, we will get snowed under.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, the conceit of I am—the real antidote to that is the realization of emptiness. Even before that, if you can negate a permanent partless independent self, that’s helping to get rid of the conceit. Or if you negate a self-sufficient, substantially existent self, that’s going to help you too.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes. It makes you think, like, “Why are they in this order?” It’s a good thing to think about because in some ways you put ignorance first because it’s the root of the whole thing. I’m thinking maybe attachment comes first. Because that one we’re really familiar with. It makes us feel good and it leads us to be greedy. Yes, in some way it’s obvious. Are you on this same topic?

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, that’s true and with attachment we can be attached to our other negative emotions, can’t we? Yes, and then that anger follows naturally after attachment because when you don’t get what you want you get angry. Then with conceit, we seem to be swinging back towards building up the self again. Yes, and then ignorance, kind of sandwich ignorance in there.

Then doubt—then you’re really going towards wrong thinking. Ignorance is, you’re obscured and your wrong grasping doubt is you’re really beginning to form a view about that. That’s erroneous. Then afflictive views are you’re really stuck in the middle of a bunch of wrong views. Yes, but of course, afflictive views can also be said to be a form of ignorance, too. It’s not like these things are totally separated from one another.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Why does the inherit wisdom of the mind allow these negative emotions to become so strong and lead us in a way that’s opposite to wisdom? Because our inherent wisdom is sleeping. Because our inherent wisdom is teeny, teeny, teeny. It’s sleeping and it needs to grow, and it needs some exercise, needs to be developed. Yes.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Good question. In trying to abandon attachment to others, how do we connect with them in a balanced way so that we don’t get attached on one hand, and so that we don’t become like an ice cube so that over time, so I’m not detached? On the other hand, we don’t want to go to either of those things. If you say, “Oh, you’re so wonderful. I can’t let you go.” And like, “Yes, whatever.” You can’t imagine being a Buddha and happy, and have in your mind either one of those two ways, can you? That’s just not going to cut it. I think, especially, what I find very helpful is the more we are capable of generating love and compassion and using those as ways to connect with others, then the less we need to rely on attachment as a way of connecting to others. Because right now, we only know attachment, don’t we? It’s like, “Oh, that person makes me happy.” Whereas when we really take some time and try and develop love, and here, I’m meaning the kind of love in Buddhist practice that is impartial, and can be extended towards all living beings, simply because they exist.

It’s a love that just wants somebody to be happy because they exist, not because they do something wonderful for us. Similarly, compassion, wanting them to be free of misery. Again, simply because they exist, not because they are somebody special to us. I think the more that we can cultivate love and compassion, then attachment just becomes superfluous and unnecessary and a big pain in the neck. I think that’s one thing that is very helpful. Another thing is that when I see that I’m getting attached to some ordinary person, then I remember I am an ordinary being, obscured by ignorance, anger, and attachment. This other person is an ordinary being, again plagued by ignorance, anger, and attachment. How are we going to bring each other happiness? Or, how is this person going to bring me happiness? If my mind is overcome by afflictions, how are they going to make me happy, with my afflicted mind, and their mind is overwhelmed by affliction, how am I ever going to make them happy? I find that very good for lessening the attachment.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes. It’s hard to cultivate attachment because we’re surrounded by objects of attachment. Yes, so it’s difficult to recognize attachment, and cultivate balance and non-attachment when we’re surrounded by objects of attachment. Do we have to stay away sometimes from objects of attachment? Yes. When our attachment is too strong, and we just go crazy with something then we have to stay away from it. Because our mind is just, it goes bonkers. I mean, if you weighed 300 pounds, are you going to be able to go to the ice cream parlor, and have a chat with your friend and not buy ice cream? That’s hard. Be kind to yourself, don’t go near the ice cream parlor. In the same way, when there are other things that we’re very, very attached to, then we keep a respectful distance from them. So that we can then cultivate our wisdom mind that can see the disadvantages of getting attached to those things and can see how those things aren’t worthy objects of attachment. This is part of the idea behind monastic precepts: they help us separate from objects of attachment.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: How do you lessen the attachment? The same thing, practice generosity instead of practicing possessiveness, transform your mind. You take delight in giving instead of delight in procuring? Yes, think of the virtue that you create by sharing what you have, by being generous, and the nonvirtue you create when you’re only thinking of yourself. “I want, I need, I have to have, isn’t this beautiful? It’s all for me.”

In the society, we live in, you have to be kind of strong-minded, to separate yourself from possessions, because the whole society’s telling us we need more and better and more and better. We had a young man come out here recently, who is an architect, and he was telling us about the tiny house movement, and people really looking at simplicity in accommodations, and it was very interesting, because he just sent me a draft of a piece he wrote about it. He was saying, for people who are low income, this thing of tiny house is really good, because you can live in a small space and live quite comfortably and not spend a lot of money. He was saying that the tiny house movement is also very popular among yuppies. I don’t know if that term is still used anymore. Is it still used, kind of the upward mobile, young people who, have everything in their hand? It’s kind of fashionable to have a tiny house with the kind of furniture that turns into something else and this and that. You’re nodding, yes, you’re from New York, yes, this is the latest thing in New York. Yes. Those people are actually getting a sense of attachment and social status from advocating for tiny houses. The point is, our mind can get attached to almost anything given the right circumstance, we can get attached to anything. So you really have to think of the disadvantages quite regularly.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: Yes, she’s commenting about us renunciates who have given up so many things, but then in the mind, it’s like, did you see that nice sweater Venerable Semkye’s wearing now? It’s nice, you noticed it and I noticed it, it’s really woven quite well. Very nice colour, maroon? Yes. Did somebody give it to you as a present? Venerable Semkye: it’s like six years old. Venerable Chodron: It looks brand new it doesn’t look six years old, it’s really nice. It kind of comes up and keeps your neck warm. Yes, it doesn’t look like my old scruffy thing that thank goodness Venerable Yeshe put back in shape by changing the things around here and that I had to wear in New York, where everybody else was wearing black.

I was in New York, wearing maroon and so were you and you and you. Where everyone was wearing very new clothes. Very new clothes and they’re all black. You’re not in New York you can put on another color. Yes, we can get, kind of perked up about our own things. Oh, and this is an example of when I said, we can get attached to almost anything. Some years ago, somebody who I hope now is not listening to this gave me a pair of shoes, you know the shoes, they look like wooden clogs of some sort, except they were gold colored. They had fur inside with a gold rim around them, gold rim for a gold clog. Perfect for a nun, right? I used them to wear into the forest. They got really beat up in the forest. They went from gold to brown, and the fur got kind of raggedy. Finally, I decided, I’m going to throw them out. I threw them out and I never throw anything out. To get me to throw something out, it’s a big thing. I threw these shoes out. The next day, I noticed there on the shoe rack. Somebody took them out of the garbage because they thought they were great. This is two or three years later, and people are still wearing them. Yes. You can get attached to almost anything. [laughter]

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: When we have wrong conclusions during an analytical meditation, is that deluded doubt? It could be deluded doubt, it could be ignorance, it could be wrong views. Yes, it could be grasping onto permanence, or, like when you do a meditation on the disadvantages of self-centeredness, and you come out hating yourself because you’re so selfish. That’s the wrong conclusion. That’s kind of ignorance of some sort. Or you meditate on death, and you come out thinking, yes, everybody dies, but I’m going to outwit it. Now, if I think of every possible way I could die, then I won’t die, because once I think of dying that way, then it won’t happen. That’s not reasonable.

One more question.

Audience: [Inaudible]

VTC: What daily practice can we do to reduce ignorance about the nature of the self?

Meditate on emptiness. And if that’s difficult to do right off the bat, think about dependent arising, look at different things, and see how they arise because of causes and conditions and go really into the causes and conditions that makes something arise. Then as your conclusion, think, well, they’re very dependent, so they can’t exist under their own power. Or look at things and analyze how they’re dependent on their parts or their characteristics and can’t exist apart from their components and then think, they’re dependent on their components, therefore they don’t have their own inherent nature. And then think about how things are merely labelled. How we give names to things and then sometimes forget that we’re the ones that gave the name to something and that, when you think about this enough, then you can really see “Wow, our names and our concepts, really reify things.” That can be quite helpful too. I think with these five there’s enough to think about. Next week we’ll do afflictive views.

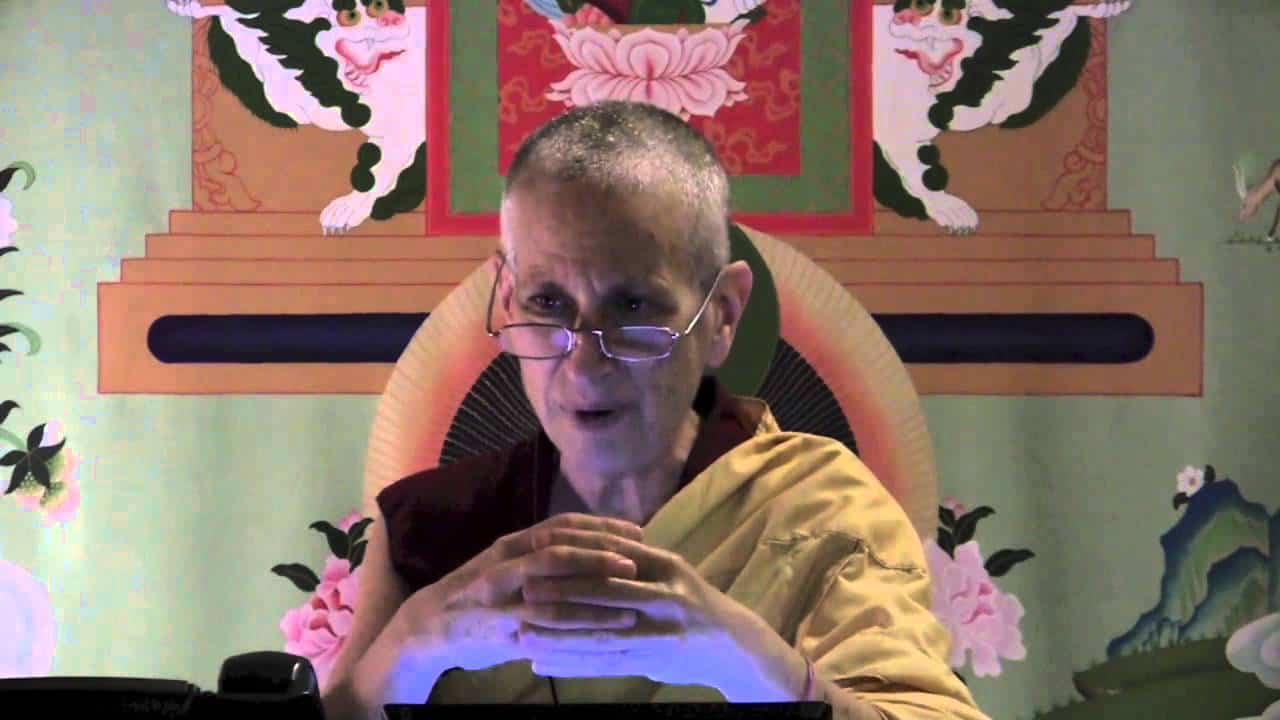

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.