How to approach Dharma practice

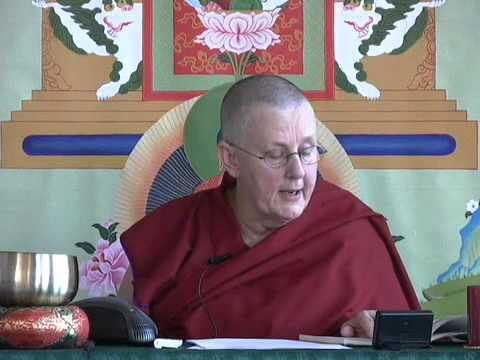

A talk given at Thösamling Institute, Sidpur, India. Transcribed by Venerable Tenzin Chodron.

It’s good to be here again with all of you. I come every year to Dharamsala and Thösamling invites me to come and give a talk every year. So it’s nice to be back and see the community growing and flourishing and new Sangha members coming. It’s really quite wonderful.

Motivation

Before we actually begin, let’s take a moment and cultivate our motivation. Think that we will listen and share the Dharma together this morning so that we can identify and then learn the antidotes to our weak areas and our faults, and so that we can recognize and learn the ways to enhance our good qualities and our talents. Let’s do this not simply for our own benefit—but by improving the state of our own mind, by gradually approaching Buddhahood, may we develop the wisdom, compassion, and power to be able to benefit all beings most effectively. So let’s keep that bodhicitta motivation in mind as we talk about the Dharma this morning. Then slowly open your eyes and come out of your meditation.

General advice on Dharma practice

I thought this morning to give some general advice on how to approach Dharma practice, because you already have teachers here who are giving you teachings in the actual Dharma studies. How to approach the practice is something really important, and how to manage everything else in our lives is very important. Because sometimes we get the feeling—at least I did at the beginning— “I’ve just got to hear a lot of teachings and do everything that the Tibetans do, and then somehow I get enlightened.” I took me falling flat on my face a few times to realize that’s not what Dharma practice is all about—that practice is all about changing what’s inside here.

It’s much easier to try and do external activities that are deemed “Dharma” and in the process to ignore the internal ones. Sometimes we think that we are getting somewhere in our practice because we can do the external activities well. However, that doesn’t go on for very long, because at some point we can’t sustain it. That’s why it is important to continually come back to focusing on the actual practice of Dharma, which is changing what is inside our own minds and hearts. Learning Tibetan is good and it is a tool. Studying philosophy is good and it is a tool. Getting ordained is excellent, it’s a tool. But the real thing is to use all these tools to change what’s inside ourselves.

I say that because it’s so easy to just get involved in the external activities: to learn lists of phenomena, learn definitions, know how to make tormas, know how to play musical instruments. We may learn all these things and think, “Oh, I am becoming a good Dharma practitioner.” But in our personal relationships we are grouchy, we’re angry, we’re irritable, we’re demanding, we’re self-centered, and we are unhappy.

The basic thing for knowing if our practice is going well is to see if our mind is becoming happier and more satisfied. For example, when love, compassion, and patience grow inside us, our mind is happier and our relationships with others go better. When our understanding of impermanence increases, our contentment with external possessions increases.

This doesn’t mean when you are unhappy, something is wrong with your practice. There are different reasons for being unhappy. If we are unhappy for a long period of time, we are missing the point somewhere along the line. But if we sometimes get unhappy or the mind gets confused, that can actually be an indication that we are ready to grow and to go deeper in our practice. This was advice that I received from a Catholic nun one time. She had been ordained about fifty years and I was ordained maybe about five at that time, so that was quite a while ago. I asked her, “What do you do when you go into crisis?” She said, “It’s indicative of the fact that you are ready to grow and go deeper in your practice. Sometimes you get to a plateau and your understanding has leveled out. You are not really pushing your boundaries, you are not really scratching the surface, you are kind of gliding along. Sometimes when a lot of stuff comes up in your mind, don’t see it as something bad, see it as new things surfacing that you can now work out, because you are ready to work them out. Before, you weren’t ready to work them out.” In other words, when we are in crisis, instead of feeling like a failure, we should think, “This is happening because I’m ready to grow and go deeper in my practice. I’m ready to work on certain aspects of myself that I wasn’t even aware of before.” Then we can rejoice at what is happening because, although it may temporarily be difficult, it is taking us in the direction of the enlightenment that we seek.

I found that very, very helpful advice because sometimes our mind gets confused. We could be practicing well for a while and then all of a sudden doubts come up, seemingly out of nowhere. Or our practice seems to be going well and then we see some really good-looking man, and then all of sudden so much attachment arises. These things happen. The real trick is to learn how to work with the mind when these things happen, so that we really stay on target and don’t get distracted. The mind is very tricky and very deceptive and we can talk ourselves into just about anything. Even if we have taken precepts we can rationalize all sorts of things in order to justify our actions. We may think, “Well, the precept doesn’t really mean this, it means that. And therefore I should be able to do this…” and we begin to slide down the slippery slope of destructive thinking and non-Dharma actions. We have to be wary when our mind is involved in preconceptions, rationalizations, justifications, and denial because that doesn’t get us anywhere good.

Using our motivation wisely in this very life

I think one of the most important things in practice is to have the long-term bodhicitta motivation. That’s the thing that really keeps us going over the long-run. The trick to stay ordained is to keep showing up. You have to keep showing up. Maybe you’re thinking, “Keep showing up? What’s that?” It means you keep showing up to your meditation cushion, you keep showing up to your community. You keep showing up to your own inner goodness and your genuine spiritual aspirations. You don’t say, “I need a holiday,” and off you go. You don’t rationalize, “I am so tired, so I’m going to sleep until nine o’clock in the morning from now on.” You don’t let your mind trick you into thinking, “People invited me to a party where there will be drugs and alcohol. I’ll go for their benefit. Otherwise they may think Buddhist monastics are out of it.” Showing up does not mean pushing; it means tuning in to what we really seek. The moment we stop showing up for our practice, the moment we stop showing up for our Dharma community and for our teacher, then our negative mind is going to take us on a journey somewhere else, which is not where we want to go.

That’s why I find that this long-term motivation is so important, because it really keeps us on track. The bodhicitta motivation keeps us focused, “What my life is about is practicing the path to enlightenment for the benefit of all beings.” This is going to take a while. They always talk about enlightenment in this life, but as His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, “Sometimes, that sounds like Chinese propaganda.” (laughter) I don’t know about you, but I look at my mind and it’s going to take longer than this life for me to become a Buddha. And that’s okay. However long it takes I don’t care, because as long I am going in the right direction, I’m getting there.

But we have this mind thinking, “I have got to get enlightened right away” we’ll become stressed and have lots of unrealistic expectations. I’m not talking about a virtuous aspiration and enthusiasm for enlightenment, but a high achieving mind that wants to do everything right and finish it off so that I can check it off my list. “I’ve got enlightened! That’s done, so now I can do what I want!” I am talking about that mind, because that mind just takes us all over the place. Rather, we have to make sure our bodhicitta has calm enthusiasm, not stressful expectations. We want to think, “I am going towards enlightenment because it is the only viable thing to do in life.”

When you think about it, we’ve done everything else: we have been born in every single realm there is to be born in; we have had every single sense pleasure; we have had every single relationship; we have had all types of high status and good reputation—we’ve had it all! They have an expression in the States that says, “Been there, done that, got the T-shirt.” We’ve done everything in samsara. What more do we really want to do that brings us any kind of happiness and joy? None of the samsaric activities we have done since beginningless time has proven satisfactory. Going down that path again is useless, it doesn’t get anywhere. It’s like the mice who keep running around in the same little maze, thinking they are getting somewhere. You don’t!

But if you really cultivate bodhicitta and say, “I am going to enlightenment,” that’s something we have never done before. That’s something that is really meaningful, not just for ourselves, but for everybody else. If we deeply feel, “This is the meaning of my life, this is the direction I’m going in,” then when we hit some bumps on the road, it doesn’t matter—because we know where we are going and we know why we are going there. We have the confidence that the path we are following will lead us towards where we want to go.

So we keep going. We get sick, it doesn’t matter. When we get sick, okay, maybe we can’t sit up in your meditation, but we can still keep our mind in a virtuous state. We have to take it easy, that’s fine; but we don’t give up the Dharma because we’re sick. Attachment may come into the mind, but we don’t “exit left” with attachment, and instead we stay focused on, “I’m going towards enlightenment.” Somebody swears at us, some of our best friends criticize us— we don’t get bummed out. Instead we realize, “This is just part of the process of samsara. It’s nothing new to be alarmed about. But I am going to enlightenment.”

If you keep coming back to your basic motivation and know where you are going, you stay on track. That’s why that motivation is so beneficial. Otherwise, if our motivation is just words “I am going towards enlightenment,” when our best friend drops us, when our parents criticize us, cut us off of their inheritance we get so upset, “Oh, the world is falling apart. Woe is me, what did I do wrong?” Or anger says, “What’s the story with them? It’s not fair that they are treating me this way,” and we are going completely berserky. Then there’s the danger that we think, “I have been practicing the Dharma and people are still treating me mean! Forget ordination. Forget the Dharma. I am going to go to find some pleasure somewhere.” That’s like jumping back into the cesspool thinking that you are going to find some happiness there.

We have to be very, very clear where we are going so that when these bumps in the road happen, they don’t disturb our mind a lot—they don’t make us go this direction or that direction. It is very easy to hear this when our mind is in a steady state and say, “Oh yes, that’s true, that’s true.” But the moment a problem comes up in our life, we forget the Dharma. You see this all the time. There are people who are going along, and the moment they have a problem, they forget the Dharma teachings. They don’t know how to apply the Dharma to their problem. Or they are going along and something really good happens and a lot of attachment comes up. They forget the Dharma because they don’t know how to apply it to their mind of attachment. They aren’t skilled in bringing their mind back to a state of balance in which they know the meaning, purpose and direction in their life. That’s really important to do because we’re in samsara and problems are going to come, aren’t they?

Looking at our expectations and attitudes

Problems come, things just don’t work the way we want them to. It’s quite natural that problems come. We are in samsara. What do we expect out of samsara? I say this as a question, because if we look, in the bottom of our mind somewhere is the thought, “I expect happiness out of samsara, I expect to get what I want, I expect other people to treat me well.” Or, “I expect to have good health.”

There is one phrase that I find very helpful, “We are in samsara, what do we expect?” I find that very helpful to say to myself when I face difficulties and problems, because we are always so taken aback when we have a difficulty or problem. It’s like, “How can this happen? It shouldn’t be happening to me. These things happen to other people but for me, I shouldn’t have problems.” We think that way, don’t we! Whereas, this is samsara, why shouldn’t we have problems? (sound of dogs barking) So now, we have to still talk louder than the dogs. (laughter) So this is samsara, why shouldn’t we have problems, what do we expect?

Of course we are going to have problems. Then the whole thing is to know how to deal with our problems and how to apply the Dharma that we are learning to deal with our problems because that’s the real purpose of the Dharma—to transform our mind. Even if you want to study, and gain all your philosophical knowledge, to be able to go through the program, you still have to be able to work with mind and make your mind happy. Otherwise, if our mind gets unhappy it becomes very difficult to do anything.

One of my teachers used to always say, “Make your mind happy!” and I would be puzzled, “If I knew how to make my mind happy, I wouldn’t be here!” I didn’t say that because it was not polite, but that was what I thought. “Make my mind happy? I can’t make my mind happy. Why not? Because this person does this, and that person says that, and I don’t like it.” Why wasn’t I happy? Because everything is not going the way I wanted it to. Everybody is not being what I want them to be. So I get unhappy. In that frame of mind, I think that to be happy I have to change everybody else so that things are happening the way I want them to. If we try and change everybody else where does that get us? Nowhere.

My mother had an expression—there are certain things your mom said when you were little that have a new meaning when you practice the Dharma—that was, “Don’t knock your head against the wall.” In other words, don’t do things that are useless, that aren’t getting you anywhere. Trying to change everybody else is knocking our head against the wall. How are we going to change everybody else? We have enough difficulties changing our own mind. What makes us think that we can change everybody else’s mind and change their behavior?

When you live in a monastic setting, this becomes so clear. So there are three things that drive you totally buggy in a monastic situation. Number one: you don’t like the schedule. Right? Anybody here who likes your daily schedule? We think, “It would be nice if we began this activity fifteen minutes earlier, and I’d like that other activity to begin fifteen minutes later.” We want to rearrange something one way or another. Nobody likes the monastic schedule. The second thing that we don’t like in the monastery is the prayers we do together, “You do them too slow; she chants them too fast; you are not chanting loud enough; you are off key.” We are not happy with the prayers, “Why are we doing this prayer? I want to do that one.” We are not happy with meditation sessions we do together—we think they’re either too long or too short. The third thing we don’t like is the kitchen in the monastery, “There is not enough protein. There is too much oil. Why are we cooking this? We had carrots yesterday. Why are we having them again today? Can’t we have something else? I can’t stand rice. The cook should make something I like.”

These three things: the schedule, the chanting sessions, and the kitchen. You are not going to like them and you know what? In any monasteries nobody likes them. This is what I tell people at Sravasti Abbey, the monastery I live in. When people come in I tell them, “You are not going to like the schedule. Nobody here likes the schedule, so just accept that. Nobody likes the way the meditation sessions are organized; everybody always wants to change them, so forget that. Nobody likes the way the kitchen is run, you’re not alone. So, forget that one too.” The sooner we accept the schedule, the meditation and chanting sessions, and the way the kitchen is run, the happier we’ll be.

I have suggested the following to the people in the Abbey but we haven’t done it yet. My idea is that everyone take turns being queen for the day. You have a day in which you make the schedule, the kitchen, and the chanting the way you want it for that day. Then you see if you are happy. Then the next day another person gets to make the schedule, and the chanting, and the kitchen the way they want. We begin to see: everybody wants it to be different. Nobody likes the way it is, everybody wants to change it slightly. We see that it is impossible to satisfy everybody. Impossible. So relax. Just relax. Follow the schedule the way it is. Adjust yourself because when you do, your mind will be peaceful and happy. If you are constantly fighting the schedule and complaining about it, you are going to be miserable.

The same way with the chanting. When I was a new nun at Kopan many years ago, we chanted the Jor Chö every morning. In it is a long list of request prayers to the lineage lamas. I didn’t know who any of them were. We chanted this long prayer in Tibetan and the person who was leading it chanted so slowly. It just drove me nuts. I would try to speed it up a little bit and everybody would give me a dirty look because I was going a little bit faster than everybody else. I was hoping that they would follow me and chant more quickly, but of course they didn’t. They continued chanting soooo slowly.

I spent most of the meditation session being unhappy and angry because I didn’t like the speed of the chanting, rather than just making my mind happy with what was. I could have made my mind happy and done the practice, I could have let my mind be happy with whatever was going on. But instead I sat there and assiduously created negative karma by being angry. How useless! But I did it anyway. It took a while to get smart.

There are these kind of things that we continually grumble about, again, and again, and again. Or, we adjust ourselves and accept the reality of the situation. We can change our attitude, and when we do so, we’ll fit in with whatever is happening when we live together as a group and as a society. If we are always trying to change everybody else, we’ll be miserable, and in addition, it won’t work.

Looking at afflictions, working together in community

Before some people are ordained they look at the sangha and think, “Look at them, they get to sit in the front row. If I get ordained I’ll get to sit in the front row too! Then people might give me some offerings, they will respect me. That kind of looks good! If I get ordained I’ll live in a peaceful place, where everybody is working on their mind and we just live in nirvana together.” (laughter) We have these kinds of romantic expectations. The problem is that our afflictions come with us into the monastery.

I really wish that the Indian government would not let my afflictions enter into the country, would not give them a visa, and would stop them at the airport. That way I could come into India and leave my afflictions outside. The same thing with the monastery—I wish that I could enter a monastery without my afflictions. But the thing is they come right in with me.

When people say, “You are escaping from life by ordaining,” I say, “Really? Try it!” If you could escape from your afflictions just by shaving your hair and changing clothes, everybody would do it. That would be a cinch, wouldn’t it? But all of our afflictions come right in with us. That is why Dharma practice is about dealing with our afflictions. The nice thing about monastic life is that we are all dealing with our afflictions together, so we know that we are all trying, that everybody here is trying. Sometimes when our mind gets negative it seems like nobody else is trying. It seems that what they are doing is trying to make us miserable. But that is not exactly it, is it? Everyone is trying to work with their mind.

Our Dharma friends are quite precious and special to us. Why? Because they know the teachings, they are trying to practice them; they are doing what they can. None of us is perfect. Having respect for our Dharma friends and friends in the monastic community is really important. We must recognize that they are trying, they are doing their best. They are just like me. Sometimes their minds get overwhelmed by confusion, by attachment, or by resentment, or jealousy. I know what that’s like because it happens to my mind sometimes too. They are just like me.

If I see my Dharma friend having a problem, I talk to her instead of criticize her. There is no use in complaining, “Why are you doing like that? You are sleeping too late. Puja is at this time. You are supposed to be there!” Instead I think and say, “You missed puja. Are you sick? Can I help?” Try to find ways to reach out and help our Dharma friends, instead of judging them and wanting them to be what we want them to be. This is so important.

Building a community with the diverse Buddhist traditions

Something wonderful that you have here in Thösamling is that you come from different Buddhist traditions. This is something special that you can build upon. When I did my training it was all within one tradition. It wasn’t until my teacher asked me to go to Singapore that I began to learn about other Buddhist traditions. In Singapore there are so many different traditions: Chinese Buddhism, Theravada Buddhism, and so on. It was an eye opening experience for me that I value.

When starting Sravasti Abbey, I was initially working with a Theravada monk and also some Chinese monastics. The way we set up our meditation session or our chanting sessions is we had mostly silent meditation, but at the beginning we would do some chanting and at the end we would dedicate. Each day we would take turns doing the initial chanting and the dedication from a different Buddhist tradition.

I found that very helpful and very beautiful because it made me see that the same meaning is expressed in different words in different traditions. I found changing the words I used to take refuge was very helpful, it made me look at refuge in a little different way. Similarly changing the verses of praise to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha helps me see their qualities in a slightly different way. I personally found that very helpful. I also learned to bow in different ways according to the various traditions—the Theravada way of bowing and the Chinese way of bowing. I also found that very helpful because each way of bowing affects your mind in a slightly different way.

In Chinese Buddhism, one purification practice is done with everyone in the room chanting “Homage to the Fundamental Teacher Shakyamuni Buddha.” While doing so, one side of the room bows while the other chants. When you bow down, you stay down for a long time. The Tibetans always say, “No, you don’t stay down for a long time. You come up quickly symbolizing to come out of samsara quickly.” Well, the Chinese do it differently: you stay down for a long time. This way of bowing completely empties your mind. Having your nose on the floor for a long time is humbling and all our rationalizations and justifications fade away. That helps you to confess and purify. While your side of the room is down, the others chant, and when you stand up, they go down while you continue the chanting. You alternate like this, and it is so beautiful. I found it very moving.

It’s completely different from what I learned in the Tibetan tradition but I found it helped my practice a lot. Learning these different things from the different traditions can be helpful for our own practice. Also, when we travel to other Buddhist countries, we understand something about their tradition, their way of chanting and bowing. We know their etiquette.

For example, I just came from Singapore where I taught in three Theravada temples. I also taught in a Chinese temple. I felt at home in each of them because I had done some training in each tradition: to become a bhikshuni I went to Taiwan to train and a few years ago, at the request of one of my Tibetan teachers, I stayed a couple of weeks in a monastery in Thailand. I found that very helpful. This helps me to see that all of the teachings come from the Buddha. We hear, “All the teachings come from the Buddha so don’t criticize any other Buddhist traditions.” You hear that said in teachings, but then what do you hear outside the teachings? “These people, they don’t have the right view,” and “Those people don’t follow Vinaya properly.” The only conclusion of all this bad-mouthing is, “I am the only one who does it right!” Imagine that. Coincidently, it’s me again who is perfect, everybody else is wrong. It’s the same old stuff.

I found learning from the different traditions helps me to not fall into that trap and to have genuine respect for the different traditions. I really respect the Buddha as a very skillful teacher who taught different things—or taught the same thing in different ways—to different people according to their aptitudes and dispositions. The Buddha was able to teach in such a way that so many different people could find a way to practice what he said. How skillful he was! Since we are aiming for Buddhahood, we want to become skillful teachers in other to reach out to as many sentient beings as possible, so we are going to have to learn to be flexible like this.

When learning about other traditions, I do not encourage jumping around from one tradition to the other. I am not encouraging you to do the “try every ice-cream flavor in the store before you eat something trip,” because that doesn’t get you anywhere. If you go from one teacher to the next teacher, and one tradition to the next tradition, and one meditation to the next meditation without sticking to anything and going deep in it, you won’t get anywhere in your practice. But once you have established your basic practice and have teachers that you trust and are sure of your direction, then you can “add the frosting” of learning from other Buddhist traditions. This will enhance your practice and you will come to appreciate the Buddha as a really tremendous teacher.

So those were just a few ideas of what I had. Let’s have some questions and share your reflections.

Questions and answers

Full ordination and one’s Dharma practice

Question (from a lay woman): I see a lot of Western nuns here in India and I wonder like how it feels not to be fully ordained. People from the West think of everybody as being equal and think it’s important that everyone that everyone should have equal access to various opportunities. How it makes you feel to be in a tradition where you don’t have that?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): How does it feel to be a nun in the Tibetan tradition where you don’t have the equal access to full ordination? In the early days—I’m speaking personally here—I didn’t even understand that there were different levels of ordination. I took the sramanerika vow in the Tibetan tradition and as time went on I learned that there was a higher ordination for women but that the lineage hadn’t come to the Tibet. I wanted to practice more deeply, so I asked His Holiness the Dalai Lama for permission to go to Taiwan and take bhikshuni vow. He gave his permission so I went and I took it.

Becoming a bhikshuni was a major step for me. It completely transformed my practice. Before taking the bhikshuni vow, I had no idea it would have such a strong impact on my practice. You can understand this only after you do it. The way it transformed my practice was that it made me grow up. You take the bhikshuni vow from a lineage of nuns and monks going all the way back to the time of the Buddha. Through their diligent practice, they have been kept this tradition alive. You feel like there is this big wave of virtue and you just plunked yourself right on the top of it and are riding on the energy of twenty-five-hundred years of other peoples’ virtue. It becomes so obvious that your opportunity to study and practice the Dharma is due to the kindness of all these monastics who came before you, and you feel, “How fortunate I am.”

Then you begin to realize, “If this big wave of virtue is going to continue, I have to contribute and make that happen.” Until that time, I had the perspective of taking whatever I could: I took teachings, I took ordination, I took opportunities. I was very, very focussed on my Dharma practice and how to advance my own practice and progress on the path. Becoming a bhikshuni made me realize that much more than my own Dharma practice is important. It’s essential that the Dharma and the monastic lineage continue to exist on this planet, in this world. That depends on there being people who are fully ordained. I can’t just sit back and think other people are going to perpetuate the Dharma for future generations. I too have a responsibility to pass this tradition on to future generations. The people who have been so kind to give it to me are probably going to die before I do, and so somebody has got to help out. Shakyamuni Buddha isn’t alive on the Earth right now, so it’s up to the sangha to preserve these precious teachings by studying and practicing them and sharing them with others. I’ve got to do my part to pass the Dharma on to future generations.

If I am going to help sustain this, I have to get my act together. I can’t just sit here and think, “My Dharma practice, my Dharma practice, my Dharma practice.” I have to think, “What can I do for the existence of the Buddhadharma in the world?” Of course that entails working on my Dharma practice, but I also have to use my Dharma practice to make the tradition continue to exist on this planet so that other people will have the same fortune that I had.

Becoming a bhikshuni made me grow up in that way and take responsibility. It made me practice better; it made me reach out to others in a different way. It made me more appreciative of my teachers and of the tradition. It made me much less self-centered. It had many good affects that I didn’t realize it would have before I took the ordination. My reason for taking the bhikshuni ordination wasn’t to have equal access. It was, “I want to keep those precepts. I want to cultivate more self-restraint than I am currently cultivating,” and precepts help you cultivate self-restraint. They act as a mirror to make you mindful and aware of your body, speech, and mind. I wanted the help that the precepts gave me and that’s why I took the ordination.

Having respect for the sangha

Question: There are a lot of monastics, but even as His Holiness says, only some of them are practicing properly. I see some monks gambling yet I’ve been taught that you’re not supposed to talk badly of Sangha. As lay people we are supposed to look up to the sangha yet we encounter some angry nuns who push us out of the way to get something. How do you have utmost respect for the Three Jewels and yet deal with the humanity of the sangha?

VTC: Oh, yes, I had that problem too. It’s important to respect the Three Jewels; but the monastic community is not one of the Three Jewels. The monastic community is the representative of the Jewel of Sangha. The Jewel of Sangha that we take refuge in is anybody who has realized emptiness directly. That’s the Sangha Jewel that is the object of refuge. The sangha community represents that. We are taught to respect the sangha community and that we create negative karma if we don’t. Yet we see people not behaving properly and we generate negative mental states in us. Or it could generate genuine concern for the existence of the Dharma. What do you do in that kind of situation?

I asked Ling Rinpoche that question many years ago. What I realized was that in my own case, as a new nun I wanted role models to look up to. I wanted really good, clean clear, perfect role models to emulate. Yet monastics are human beings with human foibles, and I was expecting these imperfect human beings to be perfect. Even if the Buddha appeared as a human being, he probably wouldn’t satisfy what I wanted as a role model.

What I wanted was perfection and perfection means that somebody does what I want them to do! That is the definition of perfection. It’s a ridiculous definition of perfection—we have to throw that out. Why should somebody doing what I want them to do and being what I want them to be indicate perfection? Sometimes what I want people to be is off the wall and I am wrong. So let’s drop that idea of Sangha being perfect. Instead, let’s realize that Sangha members are human beings, just like us. They are doing the best they can—they are trying.

If someone acts poorly, take that as an instruction for yourself about what not to do. If you see somebody getting angry or you see somebody gambling, watching kung-fu movies, or playing video games—doing what you wouldn’t expect sangha to be doing—have compassion for that person. Then think, “I have to be careful that I don’t behave like that.” In this way, use it as a lesson for yourself about what you should not do. It then becomes quite effective because lots of times the things that we are critical of are things that we also do. I find this way of thinking helpful to deal with it.

Integrity and consideration of others

There are two mental factors out the eleven virtuous mental factors that are important for being able to keep our precepts and being able to train well. These two are integrity and consideration for others.

Integrity is abandoning negative actions because you respect yourself as a practitioner and you respect the Dharma that you are practicing. It is more self-referenced.: “I am a Dharma practitioner, I don’t want to act like that.” Or, “I am trying to become enlightened. I don’t want to get stuck in this emotional rut.” It’s out of a sense of your own integrity, with a feeling of self-worth, that you abandon negativity.

The second mental factor is consideration for others. With this one, we abandon negativity because we realize that our actions affect other living beings. When you are concerned for the overall existence of the Dharma on this planet and you are wearing robes, you realize that some people will judge the value of the Dharma based on how you as an individual act. I don’t think it’s right for other people to judge the value of the Dharma based on one individual’s actions. That’s a narrow way of looking at things, but some people do that anyway. Understanding that they do that, I don’t want them to lose faith in the Dharma because that’s damaging for their practice. I want all beings to become enlightened. I want people to feel excited about Dharma practice, so I don’t want to do anything that’s going to cause somebody to lose faith, to become discouraged, or to lose confidence. For that reason I have to restrain my body, speech, and mind from doing negativities because if I don’t, I might do something that damages somebody else’s practice. Thus both integrity and consideration for others are important for keeping our precepts and behaving properly.

It is good to remember these two and to think about how our behavior impacts other people. Thinking about this makes us pause. I might feel it’s okay to go to the movies, and I may have not a negative mind when I go the movies, but other people are going to see me as a sangha member in the movies and that is not going to inspire faith in them. They are going to lose faith, and maybe the movie might affect adversely my mental state too. Watching the sex and violence in the movie is not good for me if I am trying to be celibate and peaceful. So I’d better not go to the movies for the sake of my own Dharma practice also.

They say copy the good behavior of the sangha, respect that. Don’t copy the negative behavior. The Buddha recommended that rather than focus on what others do and left undone that we become mindful of what we do and leave undone.

In general, whenever somebody is doing something that is harmful or damaging you can comment on the behavior and say that behavior is not appropriate, but don’t criticize the person who does the behavior. That person has Buddha nature, so we can’t say the person is evil. But we can say, “That behavior is not helpful, that behavior is damaging.” In that way, don’t let your mind get angry or disappointed.

When I got ordained, I had so much respect for the sangha and I really wanted to ordain and become like them. At the same time I was ordaining, there was a Tibetan monk and a Western nun, both of whom I respected, who were falling in love. They disrobed and got married. It had never entered my mind that somebody would do this, because from my perspective, if you have the good karma to become ordained, why in the world you would give it up to get married?

Seeing this happen with two people I had a lot of respect for frightened me because I realized if their mind could be overpowered by attachment due to previous negative karma, then my mind could be too. Therefore I better be very careful what’s going on in my mind and constantly apply the antidotes to any kind of romantic emotional or sexual attraction that I have for somebody else. If I don’t, some karma could ripen and take me in a direction that I don’t want to go in because my mind is confused. Seeing that happen to them, I started to do a lot of prostrations and confessing anything that I did in my previous life that could ripen in me breaking my vows or wanting to give them back. I don’t want to create that karma again and I don’t want to lose my ordination. I did a lot of purification for that and I also made, and still make, very strong prayers to keep my ordination purely and to be ordained again in my future lives. Doing the prostrations, confessions, and making those aspirations has helped me.

Take others people’s misdeeds as examples of things to purify in yourself. Who knows what karma we have from previous lives? There is no reason at all to be complacent or smug, “Oh that could never happen to me.” Because as soon as you think, “My mind could never fall under the influence of that kind of attachment, or that jealousy, or that anger,” something happens and you do. When we are complacent, it comes right smack in your face! That’s why it is better not to become complacent.

Comment from audience: You are talking about the Sangha. I just spent four or five months in Dehradun, and you had 2500 Sangha all in there together. Some of the lay people were appalled with the behavior of some monks. I thought, “Let’s think about this. Most of them are boys. They are fifteen to twenty-five year old boys.” It was almost like a giant boys’ school. Many of the monks were just starting their training. They have the karma to put the robes on, but it doesn’t mean they have a complete monastic education yet. That’s why they are there, to get an education.

Some of the nuns were just as naughty. At first I was appalled too. I was just like, “Oh, I can’t believe they are doing this! They are falling asleep on each other’s backs. This is an incredible situation and they don’t even appreciate it.” You have to learn not to judge them and as there were things I did that were just as naughty when I was young. As I thought more about it, I realizing that they have the incredible karma to be here and hear these teachings. I don’t know the far-reaching karmic results of their being here and hearing the teachings, but they certainly will be good. I have to rejoice about that. And I have to take care that I use this opportunity wisely too and not waste it.

We took bodhisattva vows three to four times a day, and once someone said to me, “Why should I be kind to him, he wasn’t very kind to me.” He was too angry at that point to hear any advice, so I thought, “We are human beings. Have compassion.” Having compassion and bodhicitta for our fellow Sangha can be hard, but it’s what we have to practice.

VTC: Thank you for sharing that.

Giving and receiving admonishment skillfully

Question: I have a question the balance between working on your own mind and the responsibility to address things with people.

VTC: The question is, when you are living in a community, it is important to work on your own mind when you see people misbehaving. But at what point do you say something to that person? You can work on your own mind and let it go, but the person is still doing that behavior that doesn’t benefit them and doesn’t benefit the community. Yet what happens if you are not very skillful and anger comes up in your own mind? Then if you say something to them, it is not skillful and they get more angry and it disturbs the community.

When we live in community, it is important to have some things clear in our mind. Number one: we are here to train—that’s our purpose. We are here to train, not to get what we want. My purpose is to train my mind, that’s why I am here. Second, we are all training our minds and we are all trying to help each other.

The way the Buddha set the sangha up was that we admonish each other. But admonish doesn’t mean scold; it doesn’t mean we yell and scream at somebody when they do something wrong. It means learning how to talk to them so that they can understand the effects of their actions on themselves and others. It is important that we learn not only how to give admonishment, but also receive admonishment. This is essential in the monastic community. In several monastic rituals, admonishment plays a key factor.

How and if you admonish someone depends on many different circumstances. One is the state of your own mind. If your own mind is angry, upset and critical, then for sure the words that come out of your mouth are probably not going to be very skillful and the other person won’t be able to hear. So you have to work with your mind. But sometimes it is not possible to completely subdue your own mind before you say something to somebody. Sometimes the situation is such that there is tension or misunderstanding that must be dealt with immediately. In that case, you have to do the best you can. Speak with as much clarity and kindness as you can, without exaggerating what they did or blaming them.

One way to speak is to say, “When you do this, I don’t know if this is your motivation and I don’t know if this is what you mean, but this is how I am perceiving it. This is causing some distress in my mind, so I’d like to talk about it.” This works much better than saying, “You are doing this and you have a bad motivation- stop it!” Instead, say, “I don’t know what your motivation is”—it’s true, we don’t know their motivation. “I don’t know what your motivation is, but my mind is making up a story about it. That story is distressing and causing imbalance in my mind. I think it would be helpful to talk about that with you.” You can approach it that way. But if you do that, you have to be ready to listen to somebody. Your mind may not be completely free from anger, but you have to be ready to listen—and listen from your heart, not just listen with your ears.

Whether and how you admonish people also depends on your relationship with them. If that person has respect for you, it becomes much easier to admonish them. Whereas if that person doesn’t have respect for you, you might say the same words as somebody they respect, but they are not going to listen. That is a fault on their part, but that’s the way we human beings are. We often look more at the messenger than the message and we lose out.

Sometimes you have to see if you are the right person to say something. Perhaps other people in the community are having the same problem and it would be better if somebody else says it. Another thing is to check when you speak to them. In some situations it is much better to go to the person individually and talk about the difficulty privately. In other situations it is better to do it as part of a group discussion.

For example, sometimes there might be a lack of clarity about a particular behavior because within the monastery we have the rules that are specifically for our monastery that are not in the precepts. There may even be a lack of clarity about how to keep the precepts. If the community has regular meetings, you can bring that doubt up. Here you would bring it up in reference to the behavior, not in reference to the person. You say, “Our community has agreed not to do such and such. Does doing XYZ behavior fall within that?” You speak about the behavior and hopefully the person who is doing it will notice that it is something that they do. That can often be a better environment for them to hear the admonishment, they don’t feel that they are being put on the spot and pinpointed.

At Sravasti Abbey we have community meetings ten days or two weeks. We meditate in the beginning and set our motivation. Then we begin with a check-in where everybody speaks one at a time and talks about what’s been going on for them in their own practice since the last community meeting. We found that to be helpful to create community harmony and to prevent people from holding things in.

At one meeting, a nun said, “I have had a lot of anger come up last week, and I know some of you have been at the other end of my anger. I apologize, and I am trying to work with my anger as best as I can.” By her owning it and admitting that she had been angry, all the other people who had experienced her anger didn’t need to say anything to her. They didn’t want to say, “You hurt my feelings. You blamed me for something I didn’t do.” No one said, “How dare you talk to me in that insulting way.” They didn’t feel need to say such things to her because she owned it herself. Her doing that completely diffused the situation. Instead, the other members of the community asked what they could do to help her.

It is helpful when you are living in a community to be able to talk about whatever problems you are having. Somebody might be feeling down or depressed or they might feel stressed out. When they open up and share what is going on inside of them, the whole community says, “What can we do to help you? If you are really tired and exhausted and that’s why you haven’t been coming to meditation session, how can we help you so that you get enough sleep or so that you don’t feel so stressed out?”

The whole community wants to help to support that person. In that way, instead of scolding and blaming which makes others become rebellious, resentful, and antagonistic, you create an environment in which people want to support each other. If you continuously and consistently explain the reasons why we have different rules and how that benefits our practice, people will understand why the community does things in a certain way. You let them know that if they have trouble following something, they should tell us and we will support them so that a solution can be found.

Transparency in community

In order for others for others to support us, we must be willing to open up and acknowledge our problems and admit our faults. This is important to do. I realized after many years of not doing it, that I didn’t know how to admit my faults to others because I thought that sine I was a nun I shouldn’t have any! So I was squeezing myself mentally, thinking, “I have got to be this perfect nun so I can’t let others know I have problems and doubts. I can’t talk about my insecurity, anger, and attachment. Since I’m a nun, I should just look good to other people, and they might lose faith if I talk about these things.”

That created so much tension inside because I was trying to become my image of a perfect nun, which is useless. We are what we are, and we try to improve from there. To do that, I found it helpful to admit my own defects—if I am struggling with something, to say that, of course in an appropriate situation and to appropriate people. For example, to say in a community meeting, “I am struggling with this or that or the other thing,” or, “I have been a little depressed,” or “I have been out of sorts,” or, “My practice is going well and I’ve had a really happy mind.” When we share that with others, we become real human beings instead of trying to put on a false image.

In our community meetings, someone may talk about their difficulties and faults in the three or four minutes that each person has to share how they’ve been. We don’t moan and groan or to try to drag the community into our own little drama. If people have that tendency, don’t let them do that. It’s not helpful for them or for others. But if you just talk for a few minutes and maybe even ask for help, then you’ll also learn how to receive other people’s help. Similarly, you’ll learn how to give support when others ask.

Sometimes we don’t see our own problems and faults, and during a community meeting someone will say, “When we were working at this or that last week you said xyz to me and that really took me aback. I don’t understand where you were coming from when you said that.” Then the other person explains and if need be, you can talk about it in the presence of the rest of the community, which sometimes is good because people are more careful with their speech when others are listening. When other people are around you don’t do your drama, you try and express yourself better.

Maybe somebody is doing something that isn’t so helpful and you have to tap them on the shoulder sometimes and say, “That’s not so beneficial to do.” I’ve done that. At Sravasti Abbey people take the eight precepts for a period of time before they ordain. One woman had taken the eight precepts, and sometimes she would pat a man in the community on the shoulder in just a friendly way, not in a sexual way. Still, I had to say to her one day, “It isn’t appropriate for someone training to be a nun to touch a man like that, even in a friendly way.” She said, “Oh! I feel like he is my brother, but you are right. I won’t do that anymore.” And it was finished. It was something that hadn’t even entered her mind not to do. These kinds of things are ways of helping people.

When other people who are senior to us try to point things out to us, lets’ try to be receptive instead of defensive, retorting, “Why are you telling me?!” As soon as we get defensive and riles, what’s happening? Ego is there, isn’t it? Part of our training is to put our palms together and say, “Thank you” when people give us feedback. It’s the last thing in the world ego wants to do, which it’s why it is good to do that.

Fear of criticism

Question: There is always a lot of talk about antidotes to anger and attachment, what would you say is the antidote to fear, especially fear of criticism and rejection?

VTC: Fear of criticism and rejection. Does anybody else have that problem? I think that is a universal problem. We are all afraid of criticism and rejection. I find it helpful to listen to people’s criticism with an open mind. Don’t listen to their tone of voice, don’t listen to the volume of the voice. Listen to the content of what they are saying. Then evaluate it and ask yourself, “Did I do that? How does that apply to me?” If it applies to us, admit , “What that person said is correct, I am sloppy in this area. Thank you for pointing that out to me.”

We don’t have to be ashamed because somebody saw our fault, because you know what? Everybody sees our faults. Pretending we don’t have them is only fooling ourselves. It’s like saying, “I don’t have a nose. Really, I don’t have a big nose.” Everybody sees our big nose, so why deny it? When somebody points out a fault and they are right, then realize, “It doesn’t mean I am a bad person. It doesn’t mean anything except that I have this quality or did that action. I know it, and so I need to be a little bit more vigilant and try to do something about it.”

On the other hand if somebody criticizes us for something that is totally off the wall, something we did not do, then they are operating with a misunderstanding. Or perhaps the person’s criticism is justified, but instead of commenting on the behavior, they trash us as a person. In the case of somebody criticizing us for something that doesn’t apply, think, “It doesn’t apply to me, so I don’t have to be upset about it. I will explain the situation to this person and give them some more information about what I was doing, why I was doing it, and how I was thinking. If they have that information, maybe they’ll settle down.” So we try to do that.

If the person still continues to speak rudely and inconsiderately to us, then think, “This is part of my bodhisattva training. If I am going to become a Buddha, I have to get used to people criticizing me. This is going to make me stronger, because if I want to benefit sentient beings, I am going to have to get used to them criticizing me.” That’s true, isn’t it? In order to help sentient beings, even the Buddha had to endure a lot of criticism.

Then think, “This person is criticizing me, I’ll just take it. It is the result of my own negative karma anyway.” If we have that fault, we should correct it. If we don’t have that fault, what to do? It’s that person’s thing and if we can help to assuage their anger, do that; but if we can’t, what to do? Then think, “

To help sentient beings, we have to get used to their criticizing us. Think about it: Do some people criticize your teachers? Look at His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Do some people criticize him? Oh you bet! The Beijing government says lots of horrible things, and even amongst the Tibetan community people say, “Yes, yes,” to His Holiness, and then do whatever they want. People act in all sorts of ways with His Holiness. It’s not that everybody loves and respects him and follows his instructions.

Does His Holiness gets depressed? Does he sits there and feel sorry for himself? No. He knows what he is doing and he has a beneficial attitude so he keeps going. When I get criticized and feel is unjust, I remember that people criticize even His Holiness. If they are going to criticize His Holiness, of course, they are going to criticize me. I have many more faults than His Holiness does! Of course they are going to criticize me! What’s so surprising about that? But, in the same way as His Holiness keeps going in his virtuous direction in spite of the criticism, I have to do that too. If I’m sure that my motivation and the action are positive, yet someone is still angry with me, I say, “You’re right, I am doing that. I can’t stop you from being mad about it. I can’t stop your suffering, and I’m sorry you’re suffering, but I will continue with what I’m doing because in my eyes it is beneficial for others in the long run.”

We’re going to end now. Let’s sit quietly for a few minutes. I call this “digestion meditation.” Think about what we talked about and remember some of the points so you can take them home with you and continue to reflect on and remember them.

Dedication

Then let’s rejoice that we were able to spend the morning in this way. Let’s rejoice in the merit we created and the merit that everybody here created. Rejoice in the goodness in the world and the merit of all living beings: whatever practices they are doing, ways they are training their mind, kindness that they are extending to others. Let’s rejoice in all of it and dedicate it all to full enlightenment.

Thank you. I really want to extend my congratulations for what you are doing in starting Thösamling. It is so important to have a nun’s community and for nuns to be well-educated and be a good example.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.