Survival of the most cooperative

The first of two talks in response to an article in the New York Times by David Brooks entitled "The Power of Altruism."

- How “fundamental selfishness” is emphasized in our society

- How the view of fundamental selfishness cynicism and skepticism

- Looking at children’s natural desire to be helpful

Part 2 can be found here: Reversing selfishness

I had another interesting article, this was from a while ago, on the “Opinion” page of the New York Times. It’s called “The Power of Altruism.” Which is nice. I’ll read it then comment on it. Actually, this is from July 8th, so it’s before the (political) conventions, but in the middle of all the ruckus.

Western society is built on the assumption that people are fundamentally selfish.

Isn’t it? That’s kind of what we’re taught in school: “Everybody’s fundamentally selfish, you need to look out for yourself because otherwise nobody else will.” It’s even taught in religion. You should take care of others and treat others as you would treat yourself, but look out for yourself first.

And definitely, I think the whole thing in evolution theory has really emphasized this, too, kind of like there’s something hardwired into our genes to be selfish, because our ultimate aim in life is to get our genes into the gene pool.

Don’t you feel that’s the purpose of your life? [laughter] Good, I’m glad you don’t. I mean, it certainly doesn’t account for all those who don’t have children. But that’s kind of the way it’s put forth, like this is your ultimate purpose in life. Otherwise, why exist? And so you’ve got to get your genesnot somebody else’s genes, because your genes are better than their genes. Why? Because they’re yours.

This is the view in society, and it’s kind of the basis of so much cynicism that we have, so that even if somebody does something good we’re skeptical: they’ve really got something in it for themselves otherwise why would they be doing it in the end? So even if somebody’s nice we don’t really trust it. And so it leads to attitudes of cynicism, being guarded, being suspicious of other living beings.

Machiavelli and Hobbes gave us influential philosophies built on human selfishness. Sigmund Freud gave us a psychology of selfishness.

That’s true, isn’t it? Our philosophical underpinnings, our psychological underpinnings.

“Children,” he wrote, “are completely egoistic; they feel their needs intensely and strive ruthlessly to satisfy them.”

That sounds more like adults than children. Doesn’t it? Children, kind of, they have sometimes a little bit more sympathy. But adults….

they feel their needs intensely and strive ruthlessly to satisfy them

This kind of view, it just… Well, he’s going to talk about this. It just prevents us from conceiving ourselves in any other way except as a self-centered being. So, growing up with that kind of cultural influence, we can’t think that we can be anything other than that. We can’t trust other people’s motivations to be anything other than that. We completely limit our possibility for growth.

Classical economics adopts a model that says people are primarily driven by material self-interest. Political science assumes that people are driven to maximize their power.

True, isn’t it? Classical economics, the whole idea of competition: “I’ve got to be better because I want to earn more, because I want more stuff.” That’s the economic view. Political science is not so much that you want the material stuff, but you want the power. And of course material wealth brings power in many cases. So again, all the theories, the whole way we look at the world, are based on selfishness.

And even if you think of art and music, and some of the things that are more expressive, emotionally expressive. There’s always you want to be the best artist. You want to be the most acclaimed musician. In being an athlete, you want to win the game, you want to be the best athlete. As if nothing is ever worthwhile just for the pure enjoyment of it. You have to get some status, some reward for it. That’s how we grow up, isn’t it?

And then he says says:

But this worldview is clearly wrong.

Isn’t that nice to hear by somebody writing in the New York Times?

In real life, the push of selfishness is matched by the pull of empathy and altruism. This is not Hallmark card sentimentalism but scientific fact.

Thank goodness he said that, because Hallmark card sentimentalism, it’s like that’s not going to be a sound philosophical basis, or a sound emotional basis. Because we send cards saying all sorts of things, that maybe we think and feel for the duration of writing the card, but not before or after. I don’t know.

So he says it’s scientific fact:

As babies our neural connections are built by love and care.

That’s really true. His Holiness talks a lot, after he had dialogues with many scientists, about the experiment showing that children who bond with somebody—their mother or some other caregiver—when they’re young, that they grow up to be more emotionally stable, that their brains develop better, that this whole thing of empathy and care and connection for others, not just thinking “me me me me me, ” is something that nourishes us.

We have evolved to be really good at cooperation and empathy. We are strongly motivated to teach and help others.

Again, His Holiness talks about, when he talks about ants and bees, how they cooperate for the good of all. So, okay, once in a while one ant colony fights with another one. But compared to the times that they have to cooperate…. If you walk up the path here before you get to the landing, on the right hand side, you’ll see at least one, sometimes more, big anthills. If you go in the daytime. So many ants, all over the place. Thousands of them. And they cooperate with each other, because they know that as one ant they cannot survive, so they have to cooperate.

The same with the bees in a hive, they have to cooperate. The same with human beings on this planet. Could any of us…. Just go into our wilderness here, go a quarter of a mile away and live on your own, and see how long you can live on your own, just even a quarter of a mile away from the Abbey. Can we live on our own? Do we know how to grow the food, make the clothes, build our shelter? Even get the tools to do any of this, do we know how to make the tools for it? No. We’re completely lost without each other. It’s impossible for us to survive.

Cooperation is really essential. That’s why His Holiness talks about it. Instead of survival of the fittest he talks about eh survival of the most cooperative. Especially in this day when we have so many weapons to kill each other very efficiently, you can really see why cooperation is really needed if as a species—let alone individuals—we’re to survive. It’s got to be cooperation, survival of the most cooperative. And that’s what really kills us, is when we don’t cooperate and we try and destroy each other because we want to be best: “I want to be the most recognized. I want to be the most talented. I want the most praise. I want, I want.” Or, “I AM.” Once you get something: “I’m better than other people. I got this. I got that. Oh you poor slob.” This kind of attitude, where in the world is that going to get us? It doesn’t do us any good at all.

So he says we are strongly motivated to teach and help each other. And if you look, all species, the adults teach the kids. If you watch the turkeys, mama turkey teaches the baby turkeys what to do, how to peck for their food, where to go. It’s very interesting. And we have to teach each other. We have to teach the younger generation. And it seems to come very naturally to us. Not just competing with each other, but really cooperating so that all of us can be better.

As Matthieu Ricard notes in his rigorous book “Altruism,” if an 18-month-old sees a man drop a clothespin she will move to pick it up and hand it back to him within five seconds, about the same amount of time it takes an adult to offer assistance.

This is a baby of a year-and-a-half, who’s a year-and-a-half years old, who will pick up a clothespin, offer it back, want to help somebody, which is about the same time as it takes an adult. Except we sometimes think, “Well, they dropped it, so why should I pick it up?” Or, “It would be nice if I picked it up, but oh my back hurts, I can’t pick it up.” We’ll think of some kind of reason, won’t we, why we can’t pick up the clothespin.

If you reward a baby with a gift for being kind, the propensity to help will decrease, in some studies by up to 40 percent.

Now this goes completely against the psychological theory that if you reward people for something they will do it more. That some studies have shown, by up to 40%, if you reward a child they won’t do it as much in the future. That’s interesting, isn’t it? Because it’s kind of like you would think they would do it more because they’re getting something out of it. But it’s as if, by rewarding them, you’re taking the real pleasure away from the kids.

And if you look at kids, they really want to help. If you’ve worked with small children, the teachers in the group know this, they want to help. When they’re really small, if you say, “Please come help me,” they want to be included. So we should foster that instead of rewarding them with something or another, but just foster, “Wow, don’t you feel good when you can help?”

And wouldn’t it be nice as adults if we started feeling that way more ourselves? “Wouldn’t it be nice if I could contribute? Wouldn’t it be nice if I could rejoice at what other people do well?” Wouldn’t it be nice if, I may not be the best, I may not contribute the most, but everybody’s contribution is valuable. And so to derive pleasure and joy simply from contributing, without measuring how much I contribute, or how good I am compared to the other person, or any of that stuff.

I think we’ll stop here, and then I’ll continue with the article tomorrow. There are a couple of more pages.

It’s interesting to think about, isn’t it? And to become more aware in our own minds of how, as adults, we may seek a reward for being cooperative. And really examine, well why, and what good does that reward really do me? Maybe come back to the attitude of a young infant…. Well, maybe not come back to the attitude of a young infant, because they are quite self-centered. But come back to Shantideva’s way of looking at things, that the joy is the process of doing it, not the reward, not winning, not being right.

Part 2 can be found here: Reversing selfishness

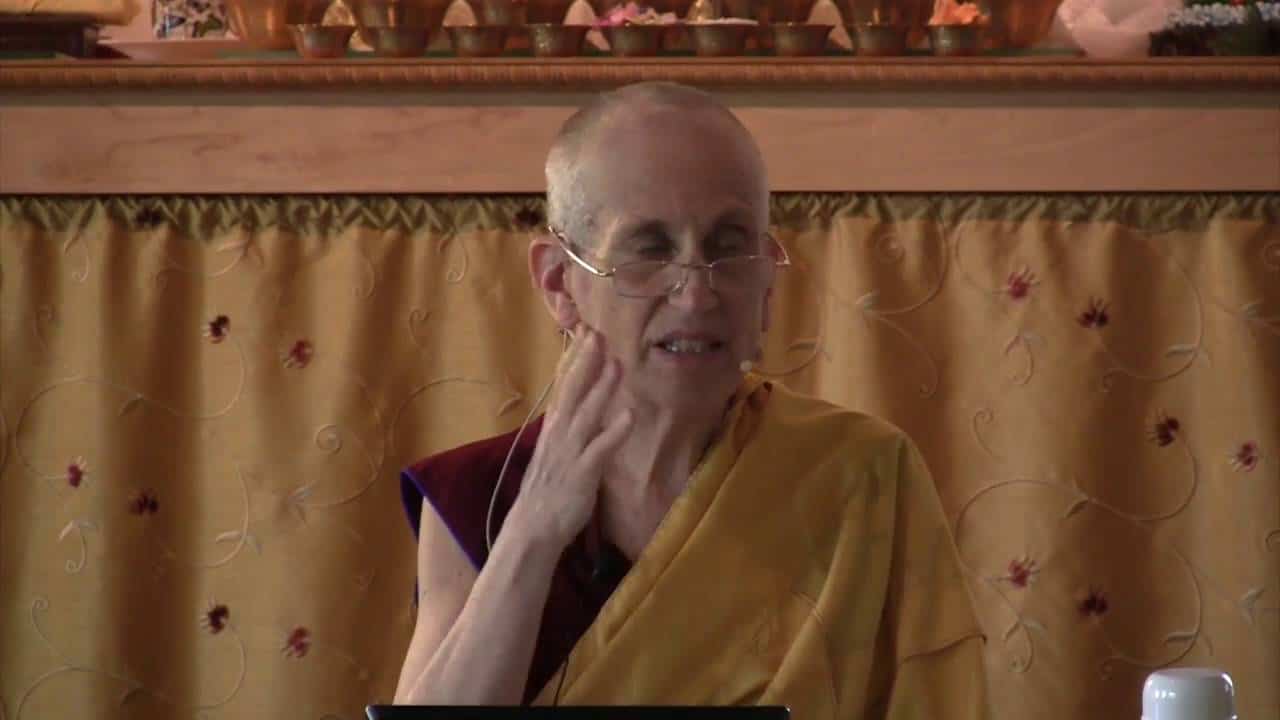

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.