Disappointment and delight—the eight worldly concerns

An interview conducted by Sara Blumenthal, associate editor of Mandala, about the eight worldly concerns. This article was initially published in Mandala in 2007.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Back in the 1970s, Lama Zopa Rinpoche compassionately taught us again and again the evils of the eight worldly concerns. Here’s what they are, listed in four pairs with each revolving around a certain kind of object.

- Taking delight in having money and material possessions, and the other one in the pair is being disappointed, upset, angry when we lose them or don’t get them.

- Feeling delighted when people praise us and approve of us and tell us how wonderful we are, and the converse is feeling very upset and dejected when they criticize us and disapprove of us—even if they are telling us the truth!

- Feeling delighted when we have a good reputation and a good image, and the converse is being dejected and upset when we have a bad reputation.

- Feeling delighted when we experience sense pleasures—fantastic sights, sounds, odors, tastes and tactile sensations—and feeling dejected and upset when we have unpleasant sensations.

These eight worldly concerns keep us pretty busy in our life. Most of our life is spent trying to obtain four of them and trying to avoid the other four.

Lama Yeshe used to talk about how we have a yo-yo mind. “I get a present! I feel so happy!” “I lost that wonderful gift. I’m so unhappy.” Somebody says “You’re wonderful,” and we feel up; somebody says, “You made a mistake,” then our mood goes down. This constant yo-yo mind is dependent on external objects and people and leaves us oblivious to how our mind is the actual source of our happiness and misery. We have bought into the appearances of this life, thinking that money and material things, praise and approval, a good reputation and marvelous sense experiences are the epitome of happiness. In our confusion, we think these things will bring us lasting and perfect well-being. This is what our consumer culture tells us and we unthinkingly believe it. Then—at least in wealthy countries—we wind up disappointed and frustrated because we thought all of these things are the cause of genuine happiness and they aren’t. They bring their own set of problems—such as fear of losing them, jealousy when others have more, and empty feeling inside our hearts.

Sara Blumenthal (SB): How can we distinguish a destructive worldly concern from something that seems almost benign, as in “This pleases my senses,” and “I’m delighted in that” and we think we’ll feel fine and won’t be disappointed if it’s taken away—where is that line crossed that we should be careful of?

VTC: We have an extraordinary ability to justify, rationalize, deny, and fool ourselves. We think, “I’m not attached. This is not disturbing my mind.” Yet the moment it is taken away from us, we freak out. That’s when we know that we have crossed the line. What is tricky is that the feeling that accompanies attachment is happiness. We ordinary beings don’t want to give up happiness, so we don’t see that by clinging and grasping at it, we’re setting ourselves up for disappointment when it goes away. If it’s a small attachment, then it’s a small disappointment. But when it’s a big attachment, we are devastated when it is gone. We have so much grief around that. For example, we see something we like—a cool car, some sports equipment, or whatever—and we buy it because we anticipate sense pleasure from it. In addition, we believe having it will create a certain image of ourselves so that others will think we’re successful and will approve of us. Does having the car fill that inner feeling of emptiness inside of us? In addition, since we’ve invested a lot in that car, when the neighbor accidentally dents it, we’re furious. It’s so sad—here we are with a precious human life and the possibility to generate impartial love and compassion for all sentient beings and to realize the nature of reality, and instead we use our lives to create a lot of negative karma procuring and protecting external things and people that we think will make us everlastingly happy.

SB: How can we check up that the feeling of happiness is not one that has a lot of attachment?

VTC: You mean before it crashes? You look at your mind. When we meditate we become aware of the “tone” or “texture” of our minds. I know when I get this kind of zing or a giddy feeling, then, definitely, it’s attachment. That’s one way to tell. When my mind says, “That’s super, how about a little bit more?” there’s attachment there, too. For example, if someone praises me, I want more. I never get to the point where I say, “That’s enough.” When my mind doesn’t want to separate from someone or something, there’s usually attachment there. Another signal is when I become more self-absorbed, relishing my own delight and forgetting about the fact that I and other sentient beings are drowning in samsara, then I know I’ve gone down the wrong path, the path of attachment.

SB: Is there a relationship between “all-pervasive suffering” and this cycle of having some worldly concern that we hang onto and experiencing disappointment?

VTC: All-pervasive suffering is having a body and mind under the influence of ignorance, afflictions and karma. As beings in the desire realm, we are glued to sense objects. So once we take those aggregates we are sitting in the middle of it—unless we practice the Dharma and make our mind strong and clear.

For somebody at my level, the eight worldly concerns are the chief obstacles to practicing the Dharma. I’m nowhere near realizing the emptiness of inherent existence or eradicating the afflictions from their root. I can barely concentrate more than a few moments when I meditate. My mind is immersed in the “mantra,” “I want, I need, give me this, I can’t stand that!”

The expression “struggling for happiness” perfectly expresses what the eight worldly concerns are about. We struggle for happiness, constantly trying to rearrange our world to get wealth, praise and approval, good reputation, and sense pleasure and to avoid lack, blame, bad reputation, and unpleasant sensations. Life becomes a battle with the environment and the people in it, as we try to be near everything we like and get far away from or destroy anything we dislike. This brings us so much grief and suffering because our mind is so reactive. We also create a lot of negative karma which brings future misery, and we’re too busy to practice the path that makes our lives meaningful and leads to genuine peace and joy.

SB: How about those things we gather around us, telling ourselves this is what we will use to help other beings?

VTC: (laughs) I can’t tell you the number of people who have said to me, “I’m going to make a lot of money and use it all for Dharma purposes.” Once in a while they send a $10 donation. I joke a lot about the eight worldly concerns because we have to laugh at how we fool ourselves. One of Lama Yeshe’s skills was that he made us laugh at ourselves while showing us how stuck and small-minded we could be.

Sometimes we Westerners misunderstand the teachings, thinking, “Without the eight worldly concerns there is no way for me to be happy, so Buddhism says it’s bad to be happy. Buddha thinks we’re virtuous only if we’re miserable.” Or we think, “I’m bad because I am attached.” We judge ourselves when there is attachment in our mind. “Can’t I just enjoy this cheesecake? Buddhism is so strict and unreasonable!”

Actually Buddha wants us to be happy and is showing us the way to peace. We have to spend time reflecting on our life experiences, discerning what happiness is and what causes it. When we figure out that the eight worldly concerns are terrorists posing as sweethearts, we will let go of many misconceptions and won’t have to battle with attachment so much, because there will be wisdom that says, “This is nice and I enjoy it, but I don’t need it.” When we have that attitude there’s so much space in the mind because then whatever we have, whoever we’re with, we are satisfied.

SB: I’m thinking of people in situations of poverty who search for worldly things. Wouldn’t it be hard to find the mental spaciousness to go beyond that?

VTC: On the one hand, it’s true that when we are in dire poverty, it is difficult to find the space to reflect on the workings of our mind. On the other hand, I have seen people who have very little yet who are incredibly generous. In many impoverished places, people recognize, “All of us are poor. We’re all in this thing called “life” together, so let’s share what we have.” Whereas in cultures where resources are plentiful, many people lack this attitude because they are so attached to things, and thus so fearful of losing them. Their ego identity is totally wrapped up in the eight worldly concerns.

For example, in Dharamsala, many years ago, an old nun with hardly any teeth invited me back to her home where she lived with her sister. It was a mud brick shack with a corrugated tin roof and dirt floor. They offered me tea and kaptse (Tibetan sweet fried cookies) and were so warm and generous.

Another time I was teaching in Ukraine and stopped in Kiev for the day to see a friend of the man who was translating for me. The food she offered us was several varieties of potatoes. That’s all she had. But we were her guests so she pulled out some chocolate she had been saving and shared it with us. Although she had little money, when we got to the train station she got some baked goods for us to have on the train.

I had a maroon cashmere sweater which I loved—talk about the eight worldly concerns! On the way to the train station the thought came into my mind to give Sasha my sweater. And instantly another thought said, “No! Get that idea out of your mind, it’s unreasonable and stupid!” There I was, someone from a wealthy country, I was only going to be there another couple of weeks, it was springtime, I didn’t really need the sweater and I could get another sweater (perhaps not a beautiful cashmere one) back in the States. But I was so attached to that sweater. My mind was so painful and an internal civil war waged the whole ride to the station, “Give her the sweater! No, you need it. Give it to her. No, she won’t like it,” on and on. Just before the train left the station, I gave her the sweater, and I’ll never forget the look of joy on her face. And to think my attachment and miserliness almost sabotaged that!

SB: We sometimes hear about the Peace Corps volunteer who comes back home and says, “This South American community where I worked has no money but they are so happy, so much happier than us.” We receive it with a lot of cynicism, thinking they must be fantasizing their experience. Or we’ll say, “If I didn’t have such a hectic life, I could be that way too.” Why is it that in our society we don’t trust that we can be happy with less?

VTC: Our attachment prevents us from seeing clearly. Not only do we have innate attachment, but also there is so much hype in Western society about the joys of consumerism, and that generates more attachment. We are terrified of questioning the hype, so we discount somebody else’s experience. Or we think, “That’s okay for them, but I couldn’t live like that.”

SB: What other tools can people use when they explore whether something is good for them? Or seems benign? When they don’t know how to analyze whether it is proper to move forward? For example, “Should I stay in my relationship or should I ordain?” “Should I take that job?”

VTC: The criteria I use for making big decisions in my life are:

- In which of these situations can I best keep ethical discipline ?

- Which situation would be most supportive for me developing bodhichitta?

- In which situation could I be of greatest benefit to others?

I don’t use the criteria, “Does it make me feel good?” That one doesn’t work!

SB: What is a good way to avoid getting attached to praise? When we receive approval and good feedback, we may wonder, “Should I listen to this praise as it might be really instructive, or might it be indulging in ego?”

VTC: When I first started teaching, people would come up and say, “That was a really good Dharma talk,” and I never knew what to say. So I asked (Buddhist teacher) Alex Berzin and he said, “Say ‘Thank you.'” I found that it works. When I say thank you, they feel satisfied. In my mind, I know that anything people praise me for is actually due to my teachers who taught me with great kindness. If somebody got some benefit from what I said, that’s good—but the praise actually goes to my teachers.

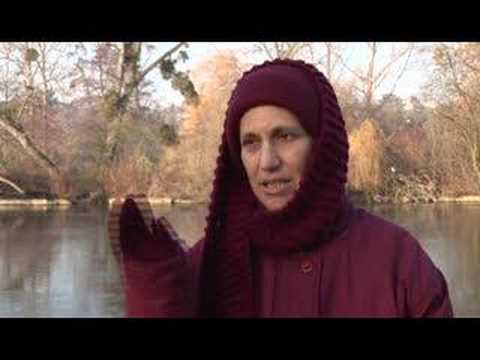

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.