Multi-tradition ordination (long version)

Tibetan precedent for giving bhikshuni ordination with a dual sangha of Mulasarvastivada Bhikshus together with Dharmaguptaka Bhikshunis

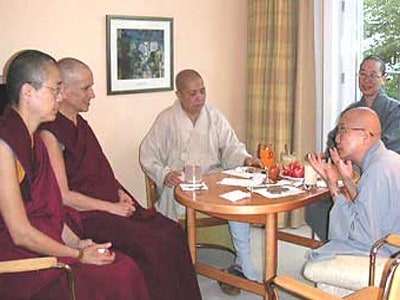

After the First International Conference on Women’s Role in the Sangha in Hamburg, Germany, in July, 2007 this paper was published in the book of the conference proceedings. (See also the shorter version of this paper that Venerable Thubten Chodron presented at the conference.)

When I received sramanerika ordination in Dharamsala, India, in 1977, I was told the story behind the blue cord on our monastic vest: it was in appreciation of the two Chinese monks who aided the Tibetans in reestablishing the ordination lineage when it was on the verge of extinction in Tibet. “Full ordination is so precious,” my teachers instructed, “that we should feel grateful to all those in the past and present who preserved the lineage, enabling us to receive the vow today.”

A bhikshu sangha of three Tibetan and two Chinese monks ordained Lachen Gongpa Rabsel (bLla chen dGongs pa rab gsal) after wide-scale persecution of the Buddhist sangha in Tibet. Lachen Gongpa Rabel was an exceptional monk, and his disciples were responsible for restoring temples and monasteries in Central Tibet and ordaining many bhikshus, thus spreading the precious Buddhadharma. His ordination lineage is the principal lineage found in the Gelug and Nyingma schools of Tibetan Buddhism today [1].

Interestingly, thirty years after learning about Lachen Gongpa Rabsel’s ordination and the kindness of the monks who ordained him, I am returning to this story of the re-establishment of the bhikshu sangha, beginning with Lachen Gongpa Rabsel’s ordination. His ordination is a precedent of multi-tradition ordination that could also be used to establish the bhikshuni ordination in Tibetan Buddhism.

In recent years discussion of the possibility of establishing the bhikshuni sangha in countries where it has previously not spread and or has died out has arisen. Everyone agrees that dual ordination by a sangha of bhikshus and a sangha of bhikshunis is the preferable mode of giving the bhikshuni ordination. In the absence of a Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni sangha to participate in such an ordination in the Tibetan community, is it possible for either:

- The ordaining sangha to consist of Mulasarvastivadin bhikshus and Dharmaguptaka bhikshunis?

- The Mulasarvastivadin bhikshu sangha alone to give the ordination?

The ordination and activities of Bhikshu Lachen Gongpa Rabsel, who restored the bhikshu lineage in Tibet after the widespread destruction of Buddhism and the persecution of the sangha during the reign of King Langdarma provides precedents for both:

- Ordination by a sangha consisting of members of different Vinaya lineages

- Adjustment of Vinaya ordination procedures in reasonable circumstances

Let us examine this in more depth.

A Precedent in Tibetan History for the Ordaining Sangha to Consist of Mulasarvastivadin and Dharmaguptaka Members

Scholars have different opinions regarding the dates of Langdarma, Gongpa Rabsel, and the return of Lumey (kLu mes) and other monks to Central Tibet. Craig Watson places Langdarma’s reign as 838 – 842 [2] and Gongpa Rabsel life as 832 – 945 [3]. I will provisionally accept these dates. However, the exact dates do not affect the main point of this paper, which is that there is a precedent for ordination by a sangha composed of Mulasarvastivadin and Dharmaguptaka monastics.

The Tibetan king Langdarma persecuted Buddhism almost to extinction. During his reign, three Tibetan monks—Tsang Rabsal, Yo Gejung, and Mar Sakyamuni—who were meditating at Chubori, took Vinaya texts and after traveling through many areas, arrived in Amdo. Muzu Salbar [4], the son of a Bon couple, approached them and requested the going-forth ceremony (pravrajya). The three monks gave him novice ordination, whereafter he was called Geba Rabsel or Gongpa Rabsel. The ordination took place in southern Amdo [5].

Gongpa Rabsel then requested full ordination, upasampada, from these three monks. They responded that since there were not five bhikshus—the minimum number required to hold an upasampada ceremony in an outlying area—the ordination could not be given. Gongpa Rabsel approached Palgyi Dorje, the monk who assassinated Langdarma, but he said he could not participate in the ordination because he had killed a human being. Instead, he searched for other monks who could, and brought two respected Chinese monks—Ke-ban and Gyi-ban [6] who joined the three Tibetan monks to give bhikshu ordination to Gongpa Rabsel. Were these two Chinese monks ordained in the Dharmaguptaka or Mulasarvastivadin lineages? Our research indicates that they were Dharmauptaka.

The Spread of Four Vinaya Traditions to China

According to Huijiao’s Biographies of Eminent Monks, Dharmakala traveled to China around 250. At that time, no Vinaya texts were available in China. Monks simply shaved their heads to distinguish themselves from the laity. On the request of the Chinese monks, Dharmakala translated the Pratimoksha of the Mahasamghika which they used only to regulate daily life. He also invited Indian monks to establish the ordination karma procedure and give ordination. This was the beginning of bhikshu ordination taking place in the Chinese land [7]. Meanwhile in 254-255, a Parthian monk named Tandi, who was also versed in Vinaya, came to China and translated the Karmavacana of Dharmaguptaka [8].

For quite a while, the model for Chinese monks seemed to be that they were ordained according to the Dharmaguptaka ordination procedure, but their daily life was regulated by the Mahasamghika Pratimoksha. Not until the fifth century, did other Vinaya texts become available to them.

The first Vinaya text introduced to Chinese communities was Sarvastivadin. It, together with its bhikshu pratimoksha, was translated by Kumarajiva between 404-409. It was well received, and according to Sengyou (d. 518), a prominent Vinaya master and historian, the Sarvastivadin Vinaya was the most widely practiced Vinaya in China at that time [9]. Soon after, the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya was also translated into Chinese by Buddhayasas between 410-412. Both the Mahasamghika and Mahisasaka Vinayas were brought back to China by the pilgrim Faxian. The former was translated by Buddhabhadra between 416-418, while the latter by Buddhajiva between 422-423.

The Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya was brought to China much later by the pilgrim Yijing, who translated it into Chinese between 700-711. According to Yijing’s observation in his traveling record, Nanhai jiguei neifa juan (composed 695–713), at that time in eastern China in the area around Guanzhong (i.e. Chang’an), most people followed the Dharmagupta Vinaya. The Mahasamghika Vinaya was also used, while the Sarvastivadin was prominent in the Yangzi River area and further south [10].

For three hundred years after the four Vinayas—Sarvastivada, Dharmaguptaka, Mahasamghika and Mahisasaka—were introduced to China, from the fifth century until the early-Tang period in the eighth century, different Vinayas were followed in different parts of China. Monks continued to follow the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya for ordination and another Vinaya to regulate their daily life. During 471-499 in the northern Wei period, the Vinaya master Facong 法聰 advocated that monastics follow the same Vinaya for both ordination and regulating daily life [11]. He asserted the importance of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya in this regard because the first ordination in China was from the Dharmaguptaka tradition and the Dharmaguptaka was by far the predominant—and maybe even the only—tradition used for ordination after the first ordination.

Dharmaguptaka Becomes the Sole Vinaya Used in China

The renowned Vinaya master Daoxuan 道宣 (596-667) in Tang period was Facong’s successor. A very important figure in the history of Vinaya in Chinese Buddhism, Daoxuan is regarded as the first patriarch of the Vinaya school in China [12]. He composed several important Vinaya works that have been closely consulted from his time to the present, and he laid the solid foundation of Vinaya practice for Chinese monastics. Among his Vinaya works, the most influential ones are Sifenlu shanfan buque xingshichao 四分律刪繁補闕行事鈔 and Sifenlu shanbu suijijeimo 四分律刪補隨機羯磨, which no serious monastic in China neglects reading. According to his Xu Gaoseng juan (Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks), Daoxuan observed that even when the Sarvastivada Vinaya reached its peak in southern China, still it was Dharmaguptaka procedure that was performed for ordination [13]. Thus, in line with Facong’s thought, Daoxuan advocated that all of monastic life—ordination and daily life—for all Chinese monastics should be regulated by only one Vinaya tradition, the Dharmaguptaka [14].

Due to Daoxuan’s scholarship, pure practice, and prestige as a Vinaya master, north China began to follow only the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya. However, all of China did not become unified in using the Dharmaguptaka until the Vinaya master Dao’an requested the T’ang emperor Zhong Zong [15] to issue an imperial edict declaring that all monastics must follow the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya. The emperor did this in 709 [16], and since then Dharmaguptaka has been the sole Vinaya tradition [17] followed throughout China, areas of Chinese cultural influence, as well as in Korea and Vietnam.

Regarding the Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya tradition in Chinese Buddhism, the translation of its texts was completed in the first decade of the eighth century, after Facong and Daoxuan recommended that all monastics in China follow only the Dharmaguptaka and just at the time that the emperor was promulgating an imperial edict to that effect. Thus there was never the opportunity for the Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya to become a living tradition in China [18]. Furthermore, there is no Chinese translation of the Mulasarvastivadin posadha ceremony in the Chinese Canon [19]. Since this is one of the chief monastic rites, how could a Mulasarvastivadin sangha have existed without it?

While the other Vinaya traditions are discussed in Chinese records, there is hardly any mention of the Mulasarvastivadin and no evidence has been found that it was practiced in China. For example, the Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya was not known to Daoxuan [20]. In the Vinaya section of the Song gaoseng zhuan, written by Zanning ca. 983, and in the Vinaya sections of various Biographies of Eminent Monks or historical records, Fozu Tongji, and so forth, there is no reference to Mulasarvastivadin ordination being given. Furthermore, a Japanese monk Ninran (J. Gyonen, 1240-1321) traveled extensively in China and recorded the history of Vinaya in China in his Vinaya text Luzong gang’yao. He listed four Vinaya lineages—Mahasamghika, Sarvastivadin, Dharmaguptaka, and Mahisasaka—and the translation of their respective Vinaya texts and said, “Although these Vinayas have all spread, it is the Dharmaguptaka alone that flourishes in the later time” [21]. His Vinaya text made no reference to the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya existing in China [22].

The Ordaining Sangha that Ordained Lachen Gongpa Rabsel

Let us return to the ordination of Lachen Gongpa Rabsel, which occurred in the second half of ninth century (or possibly the tenth, depending upon which dates one accepts for his life), at least one hundred and fifty years after Zhong Zong’s imperial edict requiring the Sangha to follow the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya. According to Nel-Pa Pandita’s Me-Tog Phren-Ba, when Ke-ban and Gyi-ban were invited to become part of the ordaining sangha, they replied, “Since the teaching is available in China for us, we can do it” [23]. This statement clearly shows that these two monks were Chinese and practiced Chinese Buddhism. Thus they must have been ordained in the Dharmaguptaka lineage and practiced according to that Vinaya since all ordinations in China were Dharmaguptaka at that time.

For Ke-ban and Gyi-ban to have been Mulasarvastivadin, they would have had to have taken the Mulasarvastivadin ordination from Tibetan monks. But there were no Tibetan monks to give it, because Langdarma’s persecution had decimated the Mulasarvastivadin ordination lineage. Furthermore, if Ke-ban and Gyi-ban had received Mulasarvastivadin ordination from Tibetans in Amdo, it would indicate that there were other Tibetan Mulasarvastivadin monks in the area. In that case, why would the Chinese monks have been asked to join the three Tibetan monks to give the ordination? Surely Tsang Rabsal, Yo Gejung, and Mar Sakyamuni would have asked their fellow Tibetans, not the two Chinese monks, to participate in ordaining Gongpa Rabsel.

Thus, all evidence points to the two Chinese monks being Dharmaguptaka, not Mulasarvastivadin. That is, the sangha that ordained Gongpa Rabsel was a mixed sangha of Dharmaguptaka and Mulasarvastivadin bhikshus. Therefore, we have a clear precedent in Tibetan history for giving ordination with a sangha consisting of Dharmaguptaka and Mulasarvastivadin members. This precedent was not unique to Gongpa Rabsel’s ordination. As recorded by Buton (Bu sTon), subsequent to Lachen Gongpa Rabsel’s ordination, the two Chinese monks again participated with Tibetan bhikshus in the ordination of other Tibetans as well [24]. For example, they were the assistants during the ordination of ten men from Central Tibet, headed by Lumey (klu mes) [25]. Furthermore, among Gongpa Rabsel’s disciples were Grum Yeshe Gyaltsan (Grum Ye Shes rGyal mTshan) and Nubjan Chub Gyaltsan (bsNub Byan CHub rGyal mTshan), from Amdo area. They, too, were ordained by the same sangha which included the two Chinese monks [26].

A Precedent in Tibetan History for Adjustment of Vinaya Ordination Procedures in Reasonable Circumstances

In general, to act as preceptor in a full ordination ceremony, a bhikshu must be ordained ten years or more. As recorded by Buton, Gongpa Rabsel later acted as the preceptor for the ordination of Lumey and nine other monks although he had not yet been ordained five years. When the ten Tibetan men requested him to be their preceptor (upadhyaya, mkhan po), Gongpa Rabsel responded, “Five years have not yet passed away since I was ordained myself. I cannot therefore be a preceptor.” Buton continued, “But Tsan said in his turn, ‘Be such an exception!’ thus the Great Lama (Gongpa Rabsel) was made preceptor… with the Hva-cans (i.e. Ke-van and Gyi-van) as assistants” [27]. In Lozang Chokyi Nyima’s account, the ten men first requested Tsang Rabsel for ordination, but he said he was too old and referred them to Gongpa Rabsel, who said, “I am unable to serve as the upadhyaya as five years have not yet elapsed since my own full ordination.” At this point, Tsang Rabsel gave him permission to act as preceptor in the bhikshu ordination of the ten men from Central Tibet. Here we see an exception being made to the standard bhikshu ordination procedure.

In the Theravada Vinaya and the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, no provision can be found for someone who has been ordained less than ten years to act as the preceptor for a bhikshu ordination [28]. The only mention of “five years” is in the context of saying that a disciple must take dependence [29] with their teacher, stay with him, and train under his guidance for five years. Similarly, in the Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya found in the Chinese Canon, no provision for acting as a preceptor if one has been ordained less than ten years can be found. Such an exception is also not found in the Mahasangika, Sarvastivada, and other Vinayas in the Chinese Canon.

However, in the Tibetan Mulasarvastivadin Vinaya, it says that that a monk should not do six things until he has been ordained for ten years [30]. One of these is that he should not serve as preceptor. The last of the six is that he should not go outside the monastery until he has been a monk for ten years. Regarding this last one, the Buddha said that if a monk knows the Vinaya well, he can go outside after five years. While there is no direct statement saying that after five years a monk can serve as preceptor, since all six activities that a monk is not supposed to do are in one list, most scholars say that what is said about one can be applied to the other five. This is a case of interpretation, applying what is said about one item in a list of six to the other five items. That is, if a monk who has been ordained five years is exceptionally gifted, upholds his precepts well, abides properly in the Vinaya code of conduct, has memorized sufficient parts of the Vinaya, and has full knowledge of the Vinaya—i.e. if he is equivalent to a monk who has been ordained ten years—and if the person requesting ordination knows that he has been a monk for only five years, then it is permissible for him to serve as preceptor. However, there is no provision for such a gifted monk to be a preceptor if he has been ordained less than five years.

Therefore, since Gongpa Rabsel acted as preceptor although he had been ordained less than five years, there is a precedent for adjusting the ordination procedure described in the Vinaya in reasonable conditions. This was done for good reason—the existence of the Mulasarvastivadin ordination lineage was at stake. These wise monks clearly had the benefit of future generations and the existence of the precious Buddhadharma in mind when they made this adjustment.

Conclusion

The ordination of Lachen Gongpa Rabsel sets a clear precedent for ordination by sangha from two Vinaya traditions. In other words, it would not be a new innovation for a bhikshuni ordination to be given by a sangha consisting of Tibetan Mulasarvastivadin bhikshus and Dharmaguptaka bhikshunis. The nuns would receive the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni vow. Why?

First, because the bhikshu sangha would be Mulasarvastivadin, and the Extensive Commentary and Autocommentary on Vinayasutra of the Mulasarvastivadin tradition state that the bhikshus are the main ones performing the bhikshuni ordination.

Second, because the bhikshu and bhikshuni vow are one nature, it would be suitable and consistent to say that the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni vow and the Dharmaguptaka bhikshuni vow are one nature. Therefore if the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni ordination rite is used, even though a Dharmaguptaka bhikshuni sangha is present, the candidates could receive the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni vow.

Applying the exception made for Gonpa Rabsel to act as a preceptor to the present situation of Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni ordination, it would seem that, for the benefit of future generations and for the existence of the precious Buddhadharma, reasonable adjustments could be made in the ordination procedure. For example, the Tibetan Mulasarvastivadin bhikshu sangha alone could ordain women as bhikshunis. After ten years, when those bhikshunis are senior enough to become preceptors, the dual ordination procedure could be done.

Tibetan monks often express their gratitude to the two Chinese monks for enabling ordination to be given to Gongpa Rabsel, thereby allowing monastic ordination to continue in Tibet after the persecution of Langdarma. In both Gongpa Rabsel’s ordination and the ordination he gave subsequently to ten other Tibetans, we find historical precedents for:

- Giving full ordination by a sangha composed of members of both the Mulasarvastivadin and the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya lineages, with the candidates receiving the Mulasarvastivadin vow. Using this precedent, a sangha of Mulasarvastivadin bhikshus and Dharmaguptaka bhikshunis could give the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni vow.

- Adjusting the ordination procedure in special circumstances. Using this precedent, a sangha of Mulasarvastivadin bhikshus could give the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni vow. After ten years, a dual ordination with the bhikshu and bhikshuni sangha being Mulasarvastivadin could be given.

This research is respectfully submitted for consideration by the Tibetan bhikshu sangha, upon whom rests the decision to establish the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni sangha. Having bhikshunis in the Tibetan tradition would enhance the existence of the Buddhadharma in the world. The four-fold sangha of bhikshus, bhikshunis, and male and female lay followers would exist. It would give many women, in many countries, the opportunity to create great merit by upholding the bhikshuni vows and progress toward enlightenment in order to benefit all sentient beings. In addition, from the viewpoint of the Tibetan community, Tibetan bhikshunis would instruct lay Tibetan women in the Dharma, thus inspiring many of the mothers to send their sons to monasteries. This increase in sangha members would benefit Tibetan society and the entire world. Seeing the great benefit that would unfold due to the presence of Tibetan nuns holding the Mulasarvastivadin bhikshuni vow, I request the Tibetan bhikshu sangha to do their utmost to make this a reality.

On a personal note, I would like to share with you my experience of researching this topic and writing this paper. The kindness of previous generations of monastics, both Tibetan and Chinese, is so apparent. They studied and practiced the Dharma diligently, and due to their kindness, we are able to be ordained, so many centuries later. I would like to pay my deep respects to these women and men who kept the ordination lineages and practice lineages alive, and I would like to encourage all of us to do our best to keep these lineages alive, vibrant, and pure so that future generations of practitioners can benefit and share in the tremendous blessing of being fully ordained Buddhist monastics.

Partial Bibliography

- Daoxuan 道宣 (Bhikshu). 645. Xu gaoseng zhan 續高僧傳 [Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks]. In Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo 大正新脩大藏經 The Chinese Buddhist Canon Newly Edited in the Era of Taisho, 1924-32. Vol. 50, text no. 2060. Tokyo: Daizokyokai.

- Davidson, Ronald. Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Fazun 法尊 (Bhikshu). 1979. “Xizang houhongqi fojiao” 西藏後弘期佛教 (The Second Propagation of Buddhism in Tibet). In Xizang fojiao (II)-Li shi 西 藏佛教 (二)- 歷史 The Tibetan Buddhism (II)- History. Man-tao Chang, ed. Xiandai fojiao xueshu congkan, 76. Taipei: Dacheng wenhua chubianshe: 329-352.

- Heirmann, Ann. 2002. ‘The Discipline in Four Parts’ Rules for Nuns according to the Dharmaguptakavinaya. Part I-III. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- _______. 2002. “Can We Trace the Early Dharmaguptakas?” T’oung Pao 88: 396- 429.

- Jaschke, H. 1995. A Tibetan-English Dictionary: With Special Reference to Prevailing Dialects. 1st print 1881. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

- Ngari Panchen. Perfect Conduct. Translated by Khenpo Gyurme Samdrub and Sangye Khandro Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1996.

- Ningran 凝然 (J. Gyonen) (Bhikshu). 1321. Luzong gangyao 律宗綱要 [The Outline of Vinaya School]. In Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo. Vol. 74, text no. 2348.

- Obermiller, E. tr. The History of Buddhism in India and Tibet by Bu-ston. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications, 1986.

- Obermiller, E. 1932. History of Buddhism by Bu-ston. Part II. Materialien zur Kunde des Buddhismus, Heft 18. Heidelberg.

- Sengyou 僧祐 (Bhikshu). 518. Chu sanzang jiji 出三藏記集 [The Collection of Records for Translation of the Tripitaka]. In Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo. Vol. 55, text no. 2145.

- Shakabpa, W.D. Tibet: A Political History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

- Snellgrove, David. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1987.

- Szerb, Janos. 1990. Bu ston’s History of Buddhism in Tibet. Wien: Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Tibetan-Chinese Dictionary, Bod-rgya tshig-mdzod chen-mo. Min tsu chu pan she; Ti 1 pan edition, 1993.

- Uebach, Helga. 1987. Nel-Pa Panditas Chronik Me-Tog Phren-Ba: Handschrift der Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. Studia Tibetica, Quellen und Studien zur tibetischen Lexikographie, Band I. Munchen: Kommission fur Zentralasiatische Studien, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Wang, Sen. 1997. Xizang fojiao fazhan shilue 西藏佛教发展史略 [A Brief History of the Development of Tibetan Buddhism]. Beijin: Chungguo shehuikexue chubianshe.

- Watson, Craig. “The Introduction of the Second Propagation of Buddhism in Tibet According to R. A. Stein’s Edition of the sBa-bZhed.” Tibet Journal 5, no.4 (Winter 1980): 20-27

- Watson, Craig. “The Second Propagation of Buddhism from Eastern Tibet according to the ‘Short Biography of dGongs-pa Rab-gSal’ by the Third Thukvan bLo-bZang Chos-Kyi Nyi-Ma (1737 – 1802).” CAJ 22, nos. 3 – 4 (1978):263 – 285.

- Yijing 義淨 (Bhikshu). 713. Nanhai jiguei neifa zhan 南海寄歸內法傳. In Taisho hinshu Daizokyo. Vol. 54, text no. 2125.

- Zanning 贊寧 (Bhikshu) and et al. 988. Song gaoseng zhan 宋高僧傳 [Biographies of Eminent Monks in the Song Dynasty]. In Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo. Vol. 50, text no. 2061.

- Zhipan 志磐 (Bhikshu). 1269. Fozu tongji 佛祖統紀 [Annals of Buddhism]. In Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo. Vol. 49, text no. 2035.

Endnotes

- This ordination lineage was brought to Tibet by the great sage Santarakshita in the late eighth century. At the time of the second propagation (Phyi Dar) of Buddhism in Tibet, it became known as the Lowland Vinaya (sMad ‘Dul) Lineage. During the second propagation, another lineage, which was called the Upper or Highland Vinaya (sTod ‘Dul) Lineage, was introduced by the Indian scholar Dhamapala into Western Tibet. However, this lineage died out. A third lineage was brought by Panchen Sakyasribhadra. It was initially known as the Middle Vinaya (Bar ‘Dul) Lineage. However, when the Upper Lineage died out, the Middle Lineage became known as the Upper Lineage. This lineage is the chief Vinaya lineage in the Kargyu and Sakya schools.

*I am indebted to Bhikshuni Tien-chang, a graduate student in Asian Languages and Literature at the University of Washington, Seattle, for doing the bulk of the research for this paper. She also graciously answered my many questions and points for clarification as well as corrected the final draft of this paper.

Return to [1] - These dates are according to Craig Watson, “The Second Propagation of Buddhism from Eastern Tibet.” Both W.D, Shakabpa, Tibet: A Political History, and David Snellgrove, Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, say Langdarma reigned 836-42. T.G. Dhongthog Rinpoche, Important Events in Tibetan History, places Langdarma’s persecution in 901 and his assassination in 902 or 906. The Tibetan-Chinese dictionary, Bod-rgya tshig-mdzod chen-mo is in accord with the 901-6 dates. Tibetans “number” years according to animals and elements that form sixty-year cycles. The uncertainty of the dates is because no one is sure to which sixty-year cycle the ancient authors were referring. Dan Martin in The Highland Vinaya Lineage says “ … the date of first entry of the monks of the Lowland Tradition (Gongpa Rabsel’s Vinaya descendants) into Central Tibet is itself far from decided; in fact this was a conundrum for traditional historians, as it remains for us today.”

Return to [2] - According to the Third Thukvan Lozang Chokyi Nyima (1737-1802) in Short Biography of Gongpa Rabsel, Gongpa Rabsel was born in the male water-mouse year. Which male water-mouse year remains uncertain: it could be 832 (George Roerich, The Blue Annals) or 892 (Wang Seng, Xizang fojiao fazhan shilue, places Gongpa Rabsel as 892 – 975, his ordination being in 911), or 952 (Tibetan-Chinese dictionary, Bod-rgya tshig-mdzod chen-mo). I assume Dan Martin would agree with the latter as he provisionally places the date of return of the Lowland monks to Central Tibet as 978, while Dhongthog Rinpoche places the return in 953. The Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center says Gongpa Rabsel lived 953-1035, but also notes, “the sources differ on the birthplace of dgongs pa rab gsal… and the year (832, 892, 952).

Return to [3] - Aka Musug Labar

Return to [4] - Fazun identifies the area as nearby present-day Xining. Helga Uebach identified the place where the two Chinese monks were from as present-day Pa-yen, southeast of Xining in his footnote 729.

Return to [5] - Their names are recorded with slight variation in different historical sources: in Buton’s History they are Ke-ban and Gyi-ban, which can also be transliterated as Ke-wang and Gyi-wang; in Dam pa’s History, they are Ko-ban and Gim-bag; Craig Watson says that these are phonetic transliterations of their Chinese names and spells them Ko-bang and Gyi-ban; in Nel-Pa Pandita’s Me-Tog Phren-Ba they are Ke-van and Gyim-phag. The Tibetan historians, for example, Buton, referred to them as “rGya nag hwa shan” (Szerb 1990: 59). “rGya nag” refers to China and “hwa shan” is a respectful term originally used in Chinese Buddhism referring to monks whose status are equivalent to upadhyaya. Here it seems simply to refer to monks.)

Return to [6] - Taisho 50, 2059, p. 325a4-5. This record does not specify the lineage of that ordination. However, ordination Karma text of Dharmaguptaka was translated into Chinese by Tandi at about the same time. So it is clear that the Karma procedure for ordination performed by the Chinese began with the Dharmaguptaka. For that reason, Dharmakala is listed as one of the patriarchs of the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya lineage.

Return to [7] - Taisho 50, 2059, p. 324c27-325a5, 8-9.

Return to [8] - Taisho 55, 2145, p 19c26-27, 21a18-19.

Return to [9] - Taisho 54, 2125, p205b27-28.

Return to [10] - Taisho 74, 2348, p.16a19-22. Facong first studied the Mahasamghika Vinaya but then realized that since the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya was used to give ordination in China, this Vinaya should be seriously studied. He then devoted himself to studying and teaching the Dharmagupta Vinaya. Unfortunately, little is known about his life, perhaps because he focused on giving oral, not written Vinaya teachings. As a result, his eminent successor Daoxuan could not include Facong’s biography when he composed Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks.

Return to [11] - However, if Dharmagupta in India is counted as the first patriarch, then Daoxuan is the ninth patriarch (Taisho 74, 2348, p.16a23-27). There are several ways of tracing back the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya masters. Ninran summarized one of them in his Luzong gang’yao: 1) Dharmagupta (in India), 2) Dharmakala (who helped establish the ordination karma in China), 3) Facong, 4) Daofu, 5) Huiguang, 6) Daoyun, 7) Daozhao, 8) Zhishou, 9) Daoxuan.

Return to [12] - Taisho 50, 2060, ibid., p620b6.

Return to [13] - Taisho 50, 2060, p. 620c7.

Return to [14] - Also spelled Chung Tzung.

Return to [15] - The Biographies of Eminent Monks of Sung Dynasty (Taisho 50, p.793).

Return to [16] - Song gaoseng zhuan, Taisho 2061, Ibid., p.793a11-c27.

Return to [17] - A living Vinaya tradition involves an established sangha living according to a set of precepts over a period of time and transmitting those precepts from generation to generation continuously.

Return to [18] - Conversation with Bhikshuni Master Wei Chun.

Return to [19] - Taisho 50, 620b19-20.

Return to [20] - Taisho 74, 2348, p16a17-18.

Return to [21] - Dr. Ann Heirman, private correspondence.

Return to [22] - Me-Tog Phren-Ba by Nel-Pa Pandita.

Return to [23] - Buton, p. 202.

Return to [24] - Buton and Lozang Chokyi Nyima say that Lumey was a direct disciple of Gongpa Rabsel. Others say that one or two monastic generations separated them.

Return to [25] - According to Dampa’s History, Grum Yeshe Gyaltsan’s ordination was performed by the same five-member sangha as Gongpa Rabsel’s (i.e. it included two Chinese monks).

Return to [26] - Buton, p. 202. According to Lozang Chokyi Nyima, Tsang Rabsel, Lachen Gongpa Rabsel’s preceptor, gave him permission to act as preceptor.

Return to [27] - According to Ajahn Sujato, it is a little known fact in the Pali Vinaya that the preceptor is not formally essential for the ordination. “Preceptor” should better be translated as “mentor,” for he plays no role in giving precepts as such, but acts as guide and teacher for the ordinand. According to the Pali, if there is no preceptor, or if the preceptor has been ordained less than ten years, the ordination still stands, but it is dukkata offence for the monks taking part.

Return to [28] - After receiving full ordination, all Vinayas require the new bhikshu to stay with his teacher for at least five years in order to learn the Vinaya, be trained as a monastic, and receive Dharma instruction.

Return to [29] - Vol 1 (ka), Tibetan numbers pp. 70 and 71, English numbers 139,140,141 of the sde dge bka’ ‘gyur. Choden Rinpoche said passage can be found in the lung gzhi section of the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya.

Return to [30]

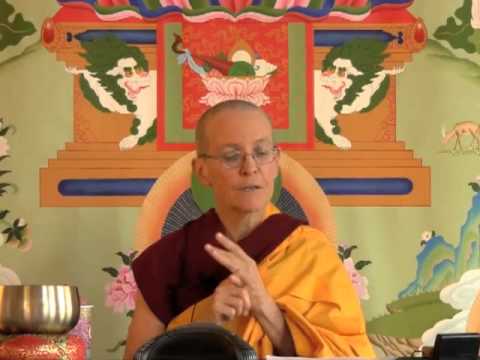

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.