The rise of women in Buddhism: Has the ice been broken?

A discussion of the issues faced by women in Buddhism, recorded at a panel discussion during the visit of H.H. The Dalai Lama as part of the supporting program in the Congress Center of Hamburg in 2014.

For many years, H.H. the Dalai Lama has encouraged women worldwide to take on leadership positions and to work as spiritual teachers. In 2007, the First International Congress of Buddhist Women took place in Hamburg. Scientists and Buddhist scholars from all Buddhist traditions examined, among other things, the question of the importance Buddha attached to women, and how they have continued and developed this over the centuries.

In this panel discussion, held during the visit of H.H. The Dalai Lama as part of the supporting program in the Congress Center of Hamburg in 2014, Dr. Thea Mohr discusses these issues with Venerable Thubten Chodron, Sylvia Wetzel, Dr. Carola Roloff and Geshe Kelsang Wangmo (Kerstin Brummenbaum), who was the first nun in Tibetan Buddhism to receive the geshe title.

What ideals do these women follow, and what difficulties have they seen and been confronted with on their way toward equality? What are the current problems, and what have these pioneers changed in the status quo and thus paved the way for other women to gain access to Buddha’s teaching? What are their visions for the future? In which direction should these developments proceed?

Thea Mohr: A wonderful evening to all of you. We’re happy to come together tonight to discuss the topic “The Rise of Women in Buddhism – Is the Ice Broken?” We thought that we would first start the discussion amongst the invited panelists, and then at 8PM include the audience in the discussion.

Introduction of Thubten Chodron

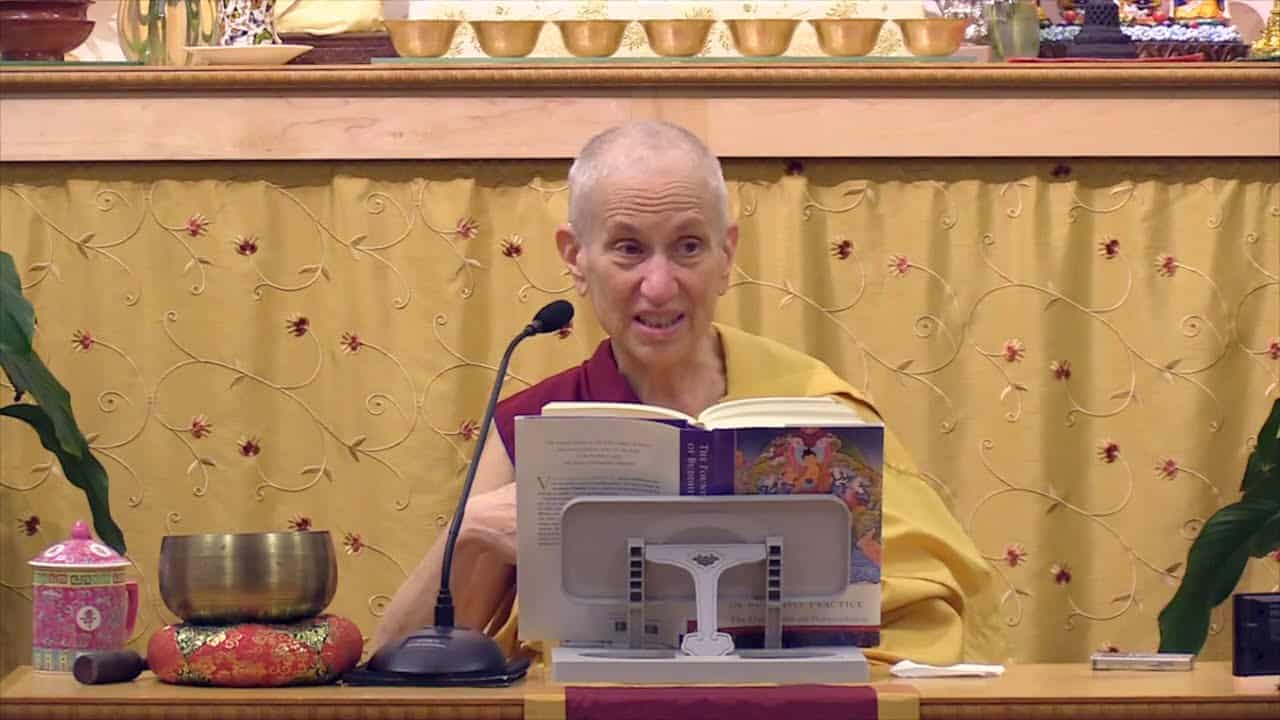

First of all, I would like to extend a warm welcome to and introduce the panelists on the podium, starting with Venerable Thubten Chodron. She was born in 1950 in the U.S., and studied Tibetan Buddhism in India and Nepal under His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Lama Zopa, and many others. She presided over the Tzong Khapa Institute in Italy and the Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Singapore, and she has propagated the Dharma worldwide. She has been a frequent guest in Hamburg and given lectures here, and she is the Abbess of Sravasti Abbey, which is located in the state of Washington in the northern part of the US. [applause]. Welcome! I would like to ask, how did you first encounter Buddhism?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: I had gone traveling in Asia and saw a lot of Buddhist images and things in India and Nepal. I came back and put them in my flat so that people would think that I was really special because I’ve been to far-out countries—even though I didn’t understand anything about Buddhism. Then in 1975, I went to a course led by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa, and the rest is history.

Thea Mohr: Thank you. How many nuns live at Sravasti Abbey?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: There are ten of us.

Thea Mohr: Great! We’ll come back to that later.

Introduction of Sylvia Wetzel

Next, I would like to introduce Sylvia Wetzel. She was born in 1949, and if I may say, she is proud to be part of the 1968 movement, yes? She was 19 when she first began getting involved with political and psychological freedom. At 28, she turned to Buddhism, particularly the Tibetan tradition. Her teachers were Thubten Yeshe, Lama Zopa, Geshe Tegchok, Ann McNeil and Rigdzin Shikpo, if I remember correctly.

You lived as a nun for two years, and this morning you told us that these two years only made you tougher and more austere, and that it wasn’t how you imagined yourself as a Buddhist nun.

Together with Carola, with Jampa Tsedroen–and we will get to Lekshe in a bit—you had supported the Sakyadhita International Conference back then as a nun, yes? And here in Germany, you are a renowned meditation teacher with innovative and creative methods. I heard that we got to experience it during the previous session. You are also a co-founder of the Buddhistischen Akademie [Buddhist Academy] and you have written countless publications with a critical lens on culture and gender roles. You are a pioneer of Buddhism. Welcome!

A question for you: how did you encounter Buddhism as a “‘68er”?

Sylvia Wetzel: In early 1977, I wrote in my diary: “I want to finally be for something, and not always against.” I led a women’s travel group to China to observe the situation of women there, and I thought to myself: “On the return trip, I’ll go and take a look at India.” In ’76, a friend of mine visited India and impressed me incredibly–a doctor and her transformation. She told me, “If you want to meditate, go to Kopan.” On the first day of my travels in India, I was in Dharamsala and came to a Tibetan party in the ashram. A boy on the street said to me, “There’s a party in the Tibetan ashram. Do you want to come?”

“Yes, a party is always good, with the Tibetans as well.” I sat in a Guru Puja and after half an hour, I had the feeling of being at home, and since then I am spending my time trying to realise what happened there.

Thea Mohr: And maybe another quick question to follow: what do you do at this Buddhist academy?

Sylvia Wetzel: I have been working for 15 years at the Dachverband der Deutschen Buddhistischen Union (DBU) [the umbrella organization of German Buddhist Unions] and wanted to find people with whom I could reflect about the cultural aspects of Buddhism, without the focus on the lineage or tradition.

We have accomplished this at the DBU with some success, but in the umbrella organization, we need to orient ourselves with different perspectives. We did this by simply gathering people in Berlin, some of whom we have known for a long time, who enjoy reflecting on Buddhism in today’s age, albeit with different methods. Innerbuddhist dialogue is a key aspect for us – that means to include all traditions while including as well the dialogue with society, i.e. politics, psychotherapy, and the religious dialogue.

Thea Mohr: Okay, we will discuss this further in a moment. Thank you very much.

Introduction of Geshe Kelsang Wangmo

Now I would like to come to Geshe Kelsang Wangmo. Please listen closely. In April of 2011, she became the first nun to be awarded the academic degree of geshe in Tibetan Buddhism. Let us give her another big round of applause.

Kerstin Brummenbaum was born in 1971 near Cologne and went to Dharamsala after her high school graduation to attend a two-week introductory course on Buddhism. Those fourteen days ended up turning into years and years. How many has it been exactly?

Geshema Kelsang Wangmo: Let me recall. I went in 1990 or 1991, so it has been 24 years.

Thea Mohr: Twenty-four years of intensive Buddhist study. The Dalai Lama and his sister have been supporting the Geshe Project for many years, and the Dalai Lama as well as the Tibetan Ministry for Religion and Culture have given you permission to take the exam [to get the geshe degree]. Why did you go to Dharamsala after high school?

Geshema Kelsang Wangmo: I had a bit of time actually after high school and did not know what I wanted to study. A few things caught my eye, but there was no major that combined all of my interests. Then I thought: “I’ll travel a bit,” and so I went to Israel.

At a kibbutz, someone told me about India: fakirs, white elephants, people meditating everywhere – that became my notion of India.

Then I went to Calcutta, India. My first shock upon arriving: no white elephants!

Well, whoever has been to Calcutta at least 20 years ago might know this: of course I had chosen the best time to go to India – it was already so hot, 40 degrees Celsius in April. And that was why I went north.

I was briefly in Varanasi and that was also unbearable, so I went further north. I still didn’t know what I wanted to study, but I somehow had the thought: “Well now it won’t work out anyway, I better drive back. I’ll stay two more weeks in the north.” I have to say, frankly the story is a little embarrassing.

The reason why I went to Dharamsala is, I first went briefly to Manali – and anyone who has been to Manali knows that it is close to Dharamsala – and in my two weeks there, while I was pondering where to go, I overheard someone saying on the […?] [unintelligible] “Dharamsala is a great place. The Dalai Lama lives there, and they have the best chocolate cake.”

Thea Mohr: Which is true!

Geshema Kelsang Wangmo: …and I thought: “I’ve heard about the Dalai Lama before, but I don’t know much about him. But after all, there is chocolate cake. Okay.” Then I went to Dharamsala because of chocolate cake. In fact, the chocolate cake in Dharamsala is truly delicious!

Whoever has been to Dharamsala knows that the atmosphere is very special, because the Dalai Lama, as well as many Tibetan monks and nuns, lives there. There is definitely a very special, very tranquil atmosphere despite all the tourists. That atmosphere simply fascinated me after I arrived, and then I thought: “I’ll stay here two to three weeks and then I’ll see.” I did a Buddhist course that captivated me, and from then on, I continued further and further, becoming a nun and beginning my [Buddhist] studies.

Thea Mohr: And how was it like to have only monks as your classmates?

Geshema Kelsang Wangmo: I mean, that was not planned as well. I actually wanted to study together with nuns, but it was challenging during that time. There were in fact nuns who were studying, but it was difficult for them. I was in a tight situation and couldn’t get accepted. Other nunneries didn’t exist yet, so I just enrolled at the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics. It was difficult – forty monks and one nun – but I learned a great deal from my classmates. Many good things came from that [experience] and I am very grateful, but it was not easy.

Thea Mohr: I can imagine that. And how did those monks who were your classmates react to the fact that you are now the first nun to hold practically the same academic degree as they do?

Geshema Kelsang Wangmo: Oh, positively. My classmates have actually always been supportive of me, particularly when it came to my studies. In general, every Tibetan – even monks who were not my classmates as well as other nuns – has really supported me. Everyone I knew – the monks and nuns, including my classmates – realized the importance of studies and were always supportive in that regard. When I was sick, [they would say to me,] “Get well soon! You have to come to the debate, okay?”

Introduction of Venerable Jampa Tsedroen

Thea Mohr: Nice. Yes, great that you have joined us tonight! I will now go to Dr. Carola Roloff, maybe better known as Jampa Tsedroen. She was born in 1959 and has been a research fellow and lecturer at the University of Hamburg for quite some time. I vividly recall how you organized in 1982 the first visit of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Hamburg. That was a large gathering, which was topped later by a larger gathering in Schneverdingen, the year of which I don’t remember.

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: That was 1998 – no, it actually occurred in 1991 here at the CCH, during the “Tibet Week” under the patronage of Karl Friedrich von Weizsäcker. At that time there wasn’t the large hall with a capacity of 7000 people yet. There was only this auditorium that we are in now, through which the Dalai Lama walked at the end [of the event]. Next door there was a hall with a capacity of 3000 people, which was already sold out before we had even advertised the event. The tickets were gone within 2 days.

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: The visit to the fairgrounds of Schneverdingen [by the Dalai Lama] was in 1998 [Note: Reinsehlen Camp is the venue referred to here]. That was the largest project [I’ve undertaken].

Thea Mohr: You have just heard – and undoubtedly must now know – of her unbelievable organizational talent. She goes about everything with a certain meticulousness, even to the point of waking up at two in the morning and saying, “We need to comply with these safety requirements here and there.” She planned everything meticulously. Yet, you set aside your organizational talent in order to devote yourself to Buddhism/ Buddhist ideology, later studying Tibetology and Indology as well and receiving an outstanding promotion. Since 2013 she has been working at the an Academy of World Religions [Akademie der Weltreligionen] with an emphasis on “Religion and Dialogue in Modern Society” [Religion und Dialog in Moderner Gesellschaft]. In addition, she runs a DFG [German Research Foundation] research project on nun ordination, gives many lectures all around the world, and is a well-renowned scientist. I am interested in why you put your excellent organizational talents aside and devoted yourself to Buddhism.

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: Yes, as a matter of fact, the more I organized [events], the more I realized that I didn’t become a nun for this. I encountered Buddhism in 1980 and met Geshe Thubten Ngawang here in Hamburg. I was enrolled at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala as a student for the first three months, and then I moved from Holzminden in Weserbergland to Hamburg to study here with Geshe Thubten. Back then when I was still a doctor’s assistant, others always told me that I could organize very well, and the Tibetan Centre discovered this fact quickly as well. I was assigned to organize the office layout, since everything was still packed up in boxes from the last relocation because no one felt responsible for unpacking them.

At the next general meeting they were looking for a new treasurer and said, “Carola, you can do accounting,” and that is how I got the position. As the first employees came and the Center grew bigger, we purchased the house in Rahlstedt and I thought: “Well, I didn’t become a nun to become a manager.” I noticed that we didn’t have as many debates as in India; two hours of debate occurred every evening and there was class every week, just like that for novices in the monastery. The larger the Center grew, the less time there was for debate, and then at one point, it was clear that I wanted to create more content.

There were a few monks in the Center who helped to translate and later returned to lay life. Because I lived there, I always had to jump in [for them] and translate. But then at one point, I felt that I did want to study Tibetan grammar from the ground up. I had learned it on my own more or less with Geshe Thubten during our India travels as well as at the breakfast and lunch table.

Then I received a lectureship offer at that university for a position in [the Department of] Continuing Education in Science [Arbeitsstelle für wissenschaftliche Weiterbildung]. A Professor of Mathematics, who was particularly impressed by the logic founded by Dharmakirti and Dignāga, suggested that I pursue another academic degree. So then I went through second-chance education, because I did not have a high school degree. I started university studies and did a major in Tibetology with a secondary focus in classical Indology that centered around Buddhist studies. Before this, I had done fifteen years of traditional studies with Geshe Thubten and had already served as a tutor in the systematic study of Buddhism.

Thea Mohr: So you applied the same meticulousness to research as you did toward organizing. Welcome!

Introduction of Thea Mohr

And to briefly complete the introductions of the panelists on the podium, my name is Thea Mohr. I am a religious studies scholar. I have been in discussion with Carola for many years about nun ordination, and made it the topic of my thesis as well. I have been fascinated and impressed again and again [by this topic]. There has been progress, albeit small steps, but progress nonetheless.

I would like to take this opportunity to mention three people in particular, who I am delighted to have with us this evening. Please excuse me if I don’t see any others who should also be mentioned. So, when I say “Female Pioneers of Buddhism”– I will start with Lekshe.

Introduction of Karma Lekshe Tsomo

Karma Lekshe Tsomo, welcome! Karma Lekshe Tsomo is a professor of Comparative Religion in San Diego. From the very beginning, together with Sylvia and Jampa, she has been supporting and organizing Sakyadhita International. She devotes special emphasis toward the nuns in the Himalayan region, who face great difficulties to receive an education or even go to school. She founded a small monastery in Dharamsala, which had great success with limited resources. Every other year she organizes large-scale Sakyadhita conferences in Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, Taiwan, and other countries in Asia – if I remember correctly, which is unbelievable. You have continued to inspire us all with your perseverance for these international nuns. Thank you very much for coming tonight.

Introduction of Gabriele Küstermann

I would like to welcome our next guest of honor, beloved Gabriele Küstermann. As far as I recall, Gabrielle Küstermann has been closely working with the topic of women in Buddhism for thirty or forty years. She regards everything with a critical lens, but it should be mentioned here that she was one of our major supporters in 2007 when we organized the first International Nun Congress here in Hamburg. Back then, she was the chairperson of the Foundation for Buddhist Studies. I’m sorry, you weren’t the chairperson – you were the founder and led them at that time. And thanks to your tireless support and effort, we owe what we see here in Hamburg, what was established here in Hamburg for Buddhism, to you. So glad that you could come!

Introduction of Gabriela Frey

I would like to mention a third lady. Supported by Lekshe, Gabriela Frey has been very dedicated in founding an organization, a Sakyadhita department, in France. She shows deep concern for the French nuns and their ability to organize themselves, and she dedicates her heart and soul to Buddhism. She is also – let me see – a member of the Council of the European Buddhist Union. That’s so wonderful! Thank you very much.

First Topic: Reasons for becoming excited about Buddhism

Now I would like to start our discussion at the podium with the following question to our four pioneers: What was it that got you excited about Buddhism? Which ideals of Buddhism were you attracted to?

Who would like to begin?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: I think what first struck me was that I was looking for a worldview, a way to view the world, that made sense to me. Buddhism really gave me some structure, you know, talking about samsara, the nature of the mind, rebirth, [and] the possibility of full awakening. It gave me a way to understand my life and my place in the universe. Otherwise, I had no idea why I was alive and what the purpose of my life was.

The second thing that really struck me was pointing out that ignorance, anger, clinging, [and] attachment were defilements and that [the] self-centered mind was our enemy, because I didn’t think that way before. I thought I was a pretty good person until I started looking at my mind and seeing all the rubbish in it and then figured out that that was the source of my misery, not other people. So that was a big change in perspective. Also when I did the thought training teachings, they really worked and helped me deal with my emotions and improved my relationships. So I just kept on with it. When I first started I didn’t know anything about anything. Seriously. I didn’t know the difference between Buddhism and Hinduism or anything about the different traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. All I knew is that what these teachers said made sense and it helped me when I practiced it. And So I kept going back.

Thea Mohr: I need to apologize – I forgot to introduce you, dear Birgit. Birgit Schweiberer is a doctor and has acquainted herself with Buddhism for a long time. She teaches at the Tsongkhapa Institute in Italy and now she studies Buddhism in Vienna, so I’ve heard. Thank you very much for your translation. Maybe Kelsang Wangmo, you can say again what fascinated you about Buddhism?

Geshema Kelsang Wangmo: Now I’m having trouble finding words. I might need help. What I was very fascinated with in the beginning was that Buddhism places a strong emphasis on asking questions. What I learned until then – well, I grew up a Catholic and nobody ever encouraged me to question anything. In Buddhism, the first thing was to accept nothing without first questioning and analyzing it, and then to take the part that is helpful to you and to leave the rest. Thus, this was the first thing that attracted me to Buddhism.

Then, similar to what Venerable Thubten Chodron said: the idea that actually not my parents had screwed me up, or my sister or anybody else. Instead, I had to search for the underlying causes within myself by looking within. Yes, my selfishness and the resulting actions that I did [out of selfishness] and so on.

And of course to see fears that I had, strong fears, especially at that age, and insecurities – simply the normal teenager. How do you call it, “a mess.” All that. Right, that whole mess. So there were techniques in Buddhism that helped me to see things more clearly and to actually solve these problems. They initially became less and less significant, but then some of my fears and insecurities actually disappeared completely, so that I became happier. I believe that I also became a better daughter, so my mother was pretty happy too. That was really what drew me to Buddhism. And the more I did it, the more it became apparent that it really worked. What was promised – that you become more balanced, calmer and happier – was realized. It is slow, and it takes a very, very long time, but I always say to myself there is no deadline, so [I keep going].

Thea Mohr: Sylvia, what was it like for you?

Sylvia Wetzel: Yes, I have already mentioned the first point. I finally wanted to be “for” something, and the Bodhisattva ideal was my calling. That everybody is a part of it and that violence, hatred, and opposition cannot change the world. Instead, talking with, appreciating, and acknowledging others is one way.

The other thing was: I had spent a lot of time doing psychotherapy and attending workshops in Gestalt therapy. That was all great, and you felt amazing after one of those weekends, but then I’d ask myself: “What should I do at home?”

I was actually longing for a practice, and Buddhism offered me this big toolbox of exercises with which I could engage in self-cultivation. I always said during my first two or three years: “Buddhism? That is actually a self-help therapy with meditation. Great!” For me, that was what kept me going. And I knew, after Dharamsala, I would never be bored again. Which of course wasn’t my problem before either.

Thea Mohr: Jampa, what was it like for you?

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: Well, for me it was more the existential questions. Thus, the question of “where suffering comes from” worried me all the time. When I was sixteen, I read Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha multiple times, as well as The Tibetan Book of the Dead and several other books from Hesse and Vivekananda.

Then, I was actually assimilated into Protestantism and found myself in Protestant youth groups, where I spent most of my time wrestling with socio-political questions. I was also enrolled in the boarding school at a local Protestant church, where we had regular prayers and so on. I also had various religious teachers who all had a background in pedagogy and Protestantism.

However, when someone that I knew – the grandmother of my boyfriend – actually took their life, this question preoccupied me: what happens after you die, and why does the family suddenly need to suffer so much, even though they did not do anything to anyone? The Protestant pastor could not give me an answer, so I continued down this other path and continued to question. Then a friend came back from a trip to India, where he had run into Tibetan Buddhists, and told me that he was a Buddhist. I asked: “What does that mean?”

Then I got a booklet about the Four [Noble] Truths of the Buddha. I had already read something about reincarnation, more from a scientific perspective, and had assumed that it was possible that something like reincarnation could exist. Then I learned about karma [through the booklet], and suddenly I had an “Aha!” moment. That was the solution; everything fit together and could now be explained. The causes for suffering don’t need to be from this lifetime; they could also be from a previous lifetime.

These days you always have to make sure to acknowledge the teachings of karma and reincarnation [when talking about Buddhism], because these are where the most questions arise in Western Buddhism. But for me it has always made sense, even to this day, and it has led me along this path.

Second Topic: Being a Woman/Nun in Buddhism

Thea Mohr: Very nice. We’ll continue with you: so these ideals, these wonderful teachings that Buddhism has is one thing. The other thing is reality, and in reality difficulties come up quickly. Difficulties arise quickly for everyone because we approach Buddhism with our Western understanding and have the same expectations of [gender] equality. Then the world looks completely different. I would like to know: were there noteworthy situations when you felt specifically discriminated against, or other situations that you felt were beneficial, especially in relation to males?

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: Very difficult question. To be honest, I could not believe that Buddhism would actually discriminate. For decades, I’ve tried to explain it differently to myself, because I thought that it just couldn’t be that Buddhism discriminates. When I wanted to become a nun, my teacher Geshe Thubten Ngawang told me here in Hamburg: “There is a problem. The complete ordination for nuns does not exist, but we are working on it. You met Lekshe Tsomo in Dharamsala back in 1980. Why don’t you write to her and find out?”

To be fair, we received many lam rim instructions about the path to enlightenment, and it was explained that from a Buddhist point of view, one earns the most merit when one upholds the precepts of a monk or a nun. I just wanted to accumulate as much merit as possible and to receive these precepts. These monks, who were all ordained after me, were able to do all that, but I could not go any further.

I thought that was very bitter, and since the first time I asked His Holiness the Dalai Lama this question in 1982, he kept putting me off until the following year. Then in 1985, I met Thubten Chodron in the lobby, who was also very interested in this question. I asked His Holiness yet again and he replied, “I think now is the right time for you to leave. You can go to either Taiwan or Hong Kong; it doesn’t matter.” So I left in December of that year. My teacher supported me, yet I had similar experiences as Kelsang Wangmo, who spoke of them just now.

I received the full support of all the teachers that I had here in Hamburg. I applied all that I had learned from debates with them to discussions that I have in my field research with Tibetan monks about Vinaya today. That actually prepared me for all types of arguments and has served me well.

Thea Mohr: Sylvia, how was it for you?

Sylvia Wetzel: When I was at Kopan [Monastery] in 1977, there was always an hour of discussion in the afternoon with older students, who had been there for a year or a year and a half and so were experienced. One afternoon, I was in a discussion group with an American nun who had grown up in Hollywood, and she openly and fiercely declared, “I pray to be reborn as a man because it is better and has more merit.”

I was so upset that I jumped up. I couldn’t stay any longer in the discussion group, so I stormed out of the tent and ran straight into Lama Yeshe. He saw that I was furious and said, “Hello my dear, what’s happening?” I said, “Lama Yeshe, I have a question. Is “being reborn as a female is worse than a male” a definitive statement or an interpretive one?” I had already learned that there are teachings that are definitive (emptiness) and teachings which are to be interpreted.

Lama Yeshe looked at me and said, “Sylvia, do you have a problem with being a woman?” I was shocked. That moment when I said nothing seemed to last an eternity. I thought, “What should I say now? If I say ‘Yes’ – no, I cannot say that. If I say ‘No,’ then I am lying.”

Then he smiled at me and said, “Sylvia, I believe nowadays it is much more favorable to be reborn as a woman, because women are more open to the Dharma and earnest in their practice.” He basically told me what I wanted to hear, but he first asked me a different question. For me, that was incredibly important. I then realized that it was about my perception of “being a woman,” which values I associated with it, and – in this sense – different definitions of gender roles, which are up to personal interpretation. I understood that, but it was still inspiring for me.

Thea Mohr: Many thanks! A question for Thubten Chodron: For many years we have discussed the reintroduction of the order of nuns in Tibetan Buddhism. Why is it so difficult to reinstate the order of nuns in Tibetan Buddhism?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: My take is that the real issue is something emotional in the men. First of all in Tibet, the Tibetan community in India is a refugee community. They lost their country, so there is a feeling of insecurity. They are trying to maintain the Dharma as much as they can, the way they had it in Tibet. They are confronted with modernity for the first time. So this whole issue of women wanting to participate in an equal way is new to them. It’s shaking something. It’s an aspect of modernity that they don’t know how to deal with, that hasn’t fit into their paradigm. So, I think there is some underlying anxiety and insecurity and fear. Like, if you have bhikshunis, how is everything going to change? Or all of a sudden, the nuns sit in front of the monks. What would happen if that happened? Are the nuns going to build big monasteries and get lots of offerings? How will that affect us?

There are a lot of unknowns for them. I think the issue is mainly an emotional, a mental one. I don’t think the real issue is legal. It’s phrased in legal terms, so we don’t know if it’s possible to ordain people according to the Vinaya in a legitimate way. But my feeling is often that human beings… we first decide what we believe, then we find scriptures that support it. We think that when some shift in the underlying culture and in the minds of men [happens], then they’ll find the passages, and all of a sudden everybody, all together, will say: “Oh yes, this is a good idea. We agreed with this all along.” That is my take.

At Sravasti Abbey we have a community right now of ten nuns – seven bhikshunis and three shiksamanas – and we have a number of Tibetan Lamas who come and teach at the Abbey. We let them know that we have bhikshunis here. We are ordained in the Dharmaguptaka tradition. We do the three monastic ceremonies: the posada, the fortnightly confession, [and] also Pravarana, which is the ceremony of invitation at the end of the annual retreat. We tell them that we do that. They see that our community is very harmonious and that people are practicing well. None of them have made any comment that is adverse, you know. If anything, they are encouraging. They are kind of surprised that there are bhikshunis but then they, you know, are encouraging.

Thea Mohr: Yes, I think that was a beautiful analysis. It happens a lot in life that one first makes emotional decisions and then applies a rational justification in retrospect.

Carola, you have been doing this type of research for many years, fully engaging and familiarizing yourself with the material on a rational level. We take these emotions as facts, saying: “This is simply how it is, but we don’t want [to accept] it yet.” Yet you have uncovered the rationale behind this. Maybe you can give us your impression on this.

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: I believe that would be too difficult now [to explain]. I have focused primarily on questions relating to monastic rules, which are [already] very complex. But the elaboration of those rules is too much to put on anybody [here].

But, in any case, solutions have been found. There are three different Vinaya traditions that still exist today, which belong to the three mainstream traditions of Buddhism respectively. The first is the Dharmaguptaka Tradition, which is the East Asian form of Buddhism prevalent in Korea, Vietnam, China, and Taiwan. Then there is the Theravada tradition, based primarily on the Pali Vinaya, which is prevalent in Southeast Asian countries such as Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Burma, and Thailand. Finally, there is the Mulasarvastivada tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, which has rituals that need to be performed together by monks and nuns. For example, the ordination of nuns traditionally requires monks and nuns of the same Vinaya tradition.

Because these rituals have rarely occurred in the history of Tibetan Buddhism – not happening for the past thousand years or so for one reason or another – the validity of such ordinations have always been questioned in retrospect, even if they were performed by great Vinaya scholars. Following the Congress in 2007, everyone agreed that each individual Vinaya tradition should decide what necessary steps should be taken to revive that.

In countries following the Theravada tradition, these same problems existed and the order of nuns no longer exists there. I believe that, from a scientific viewpoint, solutions have been found. When I last visited southern India in 2012 to conduct field research, I spent four entire days in intensive meetings with over twenty leading Vinaya experts from three of the largest monastic universities: Sera, Drepung, and Ganden. On the last evening, everyone from Sera Jey and Sera Mey, the monasteries that my teacher came from, was convinced that based on the Vinaya, it was really possible. However, I should not raise my hopes too high, because there is resistance from those who are against it.

This even went so far that a leading monk in the Gelugpa Tradition tried all he could to prevent my seminars from happening, which had already been scheduled months in advance. In the end, I had to submit an application to the Department of Culture and Religion in Dharamsala, which in turn had to confer with the Minister before allowing me to go there to seek approval. Only after I had received confirmation was I allowed to ask my question on this topic. Therefore, the entire process appeared at times as if we were still in the Middle Ages, and it begs the important question: “Who actually makes this decision?

Based on the rules of the order, consensus from the community is needed. But I have the feeling that everybody is kicking the bucket around, and nobody actually wants to make the decision. A Theravadan monk once said to me: “It’s similar to having many mice near a cat. They would all prefer if the cat had a bell around its neck. The only question is, which mouse is brave enough to put the bell around the cat’s neck?”

Similarly, we have letters of support from almost all of the leaders of Tibetan Buddhist traditions, but whenever meetings are set up to make a clear decision and this item on the agenda is raised, the decision-makers are not present. Instead, their representatives are there, who then say they are not authorized to make that decision. From what I see, this is a sign that they do not want to make the decision, even if everyone says otherwise and puts it in writing that they do. It is like sand in the gearbox. My suspicion is, looking at the politics, that there needs to be more discourse.

The people in that country are not yet ready [to accept these changes]. One could lose votes and make oneself unpopular by making a decision now. So let’s have a few more rounds [of discussion] and wait and see if the people are ready and a majority has been reached. And then when the majority wants it, we will make a decision. That’s how I see it anyway.

Thea Mohr: Yes, that’s a typical Asian way to maintain harmony: avoid engaging in an open conflict on the one hand, and trusting that a solution will be found or the matter will resolve itself over time on the other.

We are discussing women’s awakening/emergence [in Buddhism], and you, Sylvia, walked the monastic path for some time. Looking back at your own development with Buddhism of the European/German tradition and perhaps looking forward, would you say there is an awakening?

Women’s Awakening

Sylvia Wetzel: Definitely. I learned so much from Ayya Khema and practiced meditation with her for five years. At some point I interviewed her for Lotusblätter, and she said, “You know, Sylvia, if we women want change, then we have to bring it about ourselves. Nobody will do it for us.”

And then it clicked. I began noticing starting around ’87, when I had my first seminar “Women on the Way,” which was offered as a Buddhist seminar for women. Then I started hosting seminars for women but also a few for both genders, since I found it meaningful, toward an introduction of the theme of equality in Buddhism. At the same time, my colleague, Silvia Kolk, was tasked with introducing Buddhist ideas into the feminist scene. We always communicated well with each other.

From that day on – or around that time – I found things to be less problematic. I did not ask men for their approval and simply said, “I will just do my own thing. I am polite. I am friendly. I am accommodating.” I was in the umbrella organization, but I didn’t bring upon a great revolution or anything like that; I simply did my own thing. With sheer stubbornness I brought in the women’s point of view.

I think it’s important that a podium is not just filled with men. I think it’s important that it is not only men who write about the Dharma in Lotusblätter, and women instead write about their childbirth or household experience, or their Buddhist practice at home. Rather I believe that women should – and I put the following words in quotation marks – “be allowed to discuss real Dharma topics.”

I really made an effort to find female columnists for Lotusblätter, and I had to beg and search fifteen times harder to find women who were willing to write. Naturally I received a constant flow of articles written by men and in the end, I had to put a stop to it and wrote back to them: “Perhaps insufficient experience in Buddhism. Please come back and write an article after three more years of practice.” Well, I simply did things that way. I represented the women’s cause in a polite and friendly manner, and suddenly the atmosphere changed and I became the “token woman,” basically the alibi in all situations. It was, “Sylvia, isn’t this your concern. Please say something about it.”

I was accepted as well as respected [by others] at least. For me, it was one of the most important experiences and spurred me to continue representing the women’s cause in a polite and friendly manner. I get along well with men. Men are allowed to study with me and attend my courses. We just get along.

Thea Mohr: Ok, wishing you the best. Now I would like to ask you, Venerable Thubten Chodron, another question: I see that your books discuss strong emotions a lot, such as anger and the power of anger. Therefore, I have the impression that the issue of a female or male master is not so much your focus. Compared to Sylvia and Carola, who have expressed their dissatisfaction with patriarchy in society, it seems that you are more focused on the question of whether one’s master is an authentic Buddhist.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Yes, because my experience at the Abbey is that we have so many gender stereotypes in our minds, like, “Women are emotional, they quarrel or don’t get along with each other.” “Men are cold and can’t discuss their problems.” I found that these stereotypes really don’t hold the water when you live with people and see how they behave. His Holiness the Dalai Lama says that we are the same human beings with the same emotions and the same cares and concerns. That’s what I’m finding is true. I mean there is different variety of flavor according to gender, social classes, ethnicity and all of these things, but underneath all that, we are all the same.

Thea Mohr: It doesn’t matter which lineage is important or not?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Yes! I have a little story which I think shows how my view came about. When I lived a number of years in Dharamsala, whenever we did the Tsog Puja, you know, the monks would stand up and offer the Tsog to His Holiness, and then the Tsog – the offerings – were passed out to all participants. And the monks always did that. So, when I first went to Dharamsala I asked myself, “ How come the nuns don’t stand up and give the Tsog out? How come the nuns don’t get to pass out the offerings, what’s going on here?”

And then, one day, it really hit me. If the nuns were standing up and were passing out the offerings, then we would ask: “How come the nuns have to get up and pass out the offerings, and the monks just get to sit there and be served.”

At that moment I realized, you know: This is coming from me.

Thea Mohr: Thank you so much!

We also want to give the audience time for questions and comments. Therefore, I would like to ask the panelists a final question. We have talked about the awakening of [women in] Buddhism in the West and how such an awakening is happening right now. In your opinion, what needs to be done in the future in order to keep Buddhism appealing to women, so that it enriches their lives? What do you wish could change with regards to the Buddhist traditions? Let’s start with Kelsang Wangmo.

Venerable Kelsang Wangmo: My answer to your question is somewhat related to the topic that Jampa Tsedroen raised just now – the general situation within Tibetan society is changing and depends a lot on women.

I recognize that currently some people oppose these changes with regards to the full ordination of women, and that even some women are not fully supportive of it. Some nuns still don’t see the need to be fully ordained, because they were not fully educated in Buddhist teachings in the traditional sense. I think that now is the first time in Tibetan Buddhist history that nuns can receive the same [Buddhist] education as monks. Consequently, sooner or later more and more nuns will recognize the importance of ordination and say, “We want the full ordination.” But as long as they don’t express this, not much will happen.

I think that there will be many significant changes for the order of nuns once they receive the geshema certificate. Upon that female teachers – geshemas – will move to Western countries and teach at Buddhist centers there. That will make a big difference.

One of my wishes is that both geshes and geshemas will teach at Buddhist centers. People of Western countries will realize that even in Tibetan society, it is possible for both women and men to teach and practice Buddhism. What we see at the moment in the West is that most of the teachers – geshes – who are teaching at Buddhist centers are male. This is something that I really want to change.

I would also love to see more Buddhist scriptures translated. This is very important because there are so many scriptures that have not been translated yet and are not available in English, German, or any other Western language. The more translation work that is done, the more scriptures people get access to. This will make it easier for monks and nuns in the West, of course, since it is also not easy to be ordained in the West.

I admire my ordained colleagues (looking at Jampa Tsedroen, Thubten Chodron and Brigitte). I always had it easier in Dharamsala. There were naturally other difficulties that I encountered there, but wearing strange clothing and having a peculiar haircut was accepted. It was completely normal; nobody stared at you. I hope that this can become normalized here as well, so that more people can take the step of becoming ordained.

Becoming a monk or a nun is not necessarily important for your own practices, but it is key to the continued existence of Buddhism, because monks and nuns have the time to study Buddhism, translate scriptures, teach and hold extended meditation retreats. That is my wish: Buddhism should become normal in Western societies, so that it is no longer seen as something exotic.

I also notice that no one looks at me strangely here. But if I just go one or two hundred meters outside of this building, perhaps to a restaurant, I immediately feel: “Oh my goodness, I’m not in Dharamsala.”

So I wish that being a monk and nun becomes more normal in Western societies; that the exotic perceptions and cultural labels disappear; that people finally see the essence of Buddhism as international in scope, not just Asian; that people realize Buddhism can help every person in one way or another; and that everybody can gain insights from Buddhism. Yes, that is my wish.

Thea Mohr: Sylvia, what’s important to gain further development of Buddhism in the West?

Sylvia Wetzel: I have noticed in the last 20 years, that more and more women teach Buddhism, that more and more women are getting educated [in the Buddhist scriptures] so that they can teach. This very fact significantly changes the perception of Buddhism in Western societies.

I remember the very first “Western Teachers in Buddhism” conference, which was held in Dharamsala and also attended by Thubten Chodron. About twenty men and five women attended that conference. At the next conference, approximately a quarter of the teachers were female, and at the conference in Spirit Rock in 2000, half of the 250 teachers in attendance were women. This change created a drastically different atmosphere; it had a strong influence on [the manner of] course instruction. That’s my main focus for the future: To have more well-educated female teachers teaching Buddhism at Buddhist centers. That will have a strong positive impact.

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: What is becoming ever more evident is that we must begin to take responsibility for Buddhism in the West. We should not always be waiting for permission from someone in the Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy, or for a Tibetan person to instruct us on how to practice Buddhism in the West, because they do not feel responsible for that. I heard this today in another context – I believe you, Sylvia, mentioned it while talking about the first “Western Teachers in Buddhism” conference in Dharamsala. At this conference, His Holiness the Dalai Lama told us: “You should make things work yourselves.”

I also remember that my teacher [Geshe Thubten Ngawang] always felt that he was not that high in the Tibetan hierarchy and questioned his authority in making decisions on difficult issues alone. In 1998, he had a lengthy conversation – for over one hour – about that subject with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Schneverdingen. He returned from the talk in cheerful spirits and said to me, “His Holiness told me that I should just experiment more and have the courage to decide what I believe is right. After doing this for a few years, I could share my experiences with others, and we could discuss whether those decisions were right or needed some modifications. ” I really believe that this is one of the main issues – the misconception that authentic Buddhism can only be taught by Tibetans.

But as we see in the example of Kelsang Wangmo, even a German woman can go through education in a Buddhist monastery and attain a geshema degree [the same degree as monks]. I’m really excited by that; I would have done it myself if it were possible back then. But now we have established these educational programs for Tibetan nuns, and in two years’ time they will be the first group to graduate with a geshema degree. That’s a major accomplishment.

What’s important is that we reflect on the current state of Buddhism in Western societies – what’s working and what’s not working – and that we make decisions based on our findings.

This reminds me of the first conference on Tibetan Buddhism in Europe, which was held in 2005 in Zürich, Switzerland. All the European Dharma Centers had sent their representatives to this conference. As the moderator for one of the sessions, a Tibetan monk said that the Tibetans wondered if gender issues are so important in Western societies, why do Dharma Centers in Europe silently accept the patriarchal structures of Tibetan Buddhism?

Since then, I have been under the impression that the Tibetans also hoped for fresh impulses from the diaspora which had happened to other traditions. But this new wind never arrived. Instead, the West has taken steps backwards, and some Western monks are actually fond of it, because they can sit in the front while nuns have to sit in the back. There is something wrong with this.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Regarding the issue of women, I don’t think that Buddhism will survive in the West without gender equality.

With regards to Buddhism in general in the West, my hope is that people really start to study and understand the teachings correctly. I’ve been to a few conferences of Western Buddhist teachers, and sometimes I’ve been quite shocked. For example, at one of the conferences approximately only half of the attending teachers believed in rebirth, and this is a very central tenet of the Buddhadharma. So my concern sometimes is that people are so eager to modernize Buddhism and make Buddhism culturally relevant, that there is the danger that they throw out the Buddha with the bathwater. I think we have to go slowly and really understand the teachings, and then we can decide how to adopt the form to our own culture, but without changing the meaning.

Questions from the audience

Audience: During the meeting with His Holiness the Dalai Lama today, I noticed that the nuns were sitting in the back again. I expected that it would be segregated based on gender, such as monks on the left and nuns on the right, but the nuns are in the back again. This is even after the Dalai Lama has emphasized several times in the past that gender equality is key. So my question is: What would happen if the nuns come earlier tomorrow morning and take a seat at the front of the stage, where the monks were sitting today? Would that be possible?

Jampa Tsedroen: I think I can answer this question, because some weeks ago the organizational committee for this conference asked for my advice on how to seat the monks and nuns. And yes, just as in previous years, I proposed that monks should be seated on one side and nuns on the other. But then we realized that many geshes would attend this conference, who, according to Tibetan tradition, have to sit on the stage. However, this guideline is not specified in the Vinaya.

Anyhow, to make a long story short, the floorplan of the stage, including the seating arrangement of monks and nuns, had to be sent for approval by the representative of the Dalai Lama. They told us that the idea of having monks and nuns sitting on opposite sides would be impractical because the audience might get the impression that some monks are sitting behind nuns, which could not be the case and needed to be changed.

The organizers replied that by changing this, the press may get the impression that there are no nuns in attendance. It would seem as if only monks are sitting on the stage, which is unacceptable. In the end, the plan for the stage design had to be sent to Dharamsala, and what we see today reflects the final decision according to the official protocol in Dharamsala.

Audience: And what about a rotating seat plan?

Jampa Tsedroen: No. If you look in the book Dignity and Discipline, which was published by the second Nun Congress in 2007, you will see that His Holiness the Dalai Lama said: “Once the issues with the full nun ordination are resolved, there will still be some minor issues to be clarified (e.g. the seating of monks and nuns on stages). This is handled by the principle of consent. No single monk, not even the Dalai Lama, can make such decisions. There must be unanimous consent among the monks.”

If we look at the Vatican, we see that they still haven’t ratified the Charter on Human Rights. The reason behind this has to do with the issue of gender equality. Basically, we haven’t even achieved gender equality in Europe yet. That implies that it will take some more time.

Sylvia Wetzel: I would like to add to what she said. I forgive the Tibetans everything; after all, they entered modern times in 1959, which is why I understand if they still hold patriarchal viewpoints. I find it much more problematic when my Western colleagues, both male and female, express themselves in a patriarchal way. So, I forgive the Tibetans everything; they gave me the precious gift of Dharma. They can take another 300 years to adjust to the new era. It took Europe 300 years, despite the Age of Enlightenment.

Thea Mohr: Yes, I believe you were next and then the lady on my left, or the audience’s right.

Audience: My question does not necessarily refer to monks or nuns; it’s more about the dignity of women in India. The media is full of articles about terrible rape crimes. I cannot comprehend it, but as we have many people here who know India well, maybe you could give me some form of an answer.

Jampa Tsedroen: Maybe I can quickly comment on this one. Indeed, even during the Buddha’s time, rape existed. That is one of the reasons why the Buddha proclaimed that nuns should not meditate under trees, but in houses built by the monks. The issue of gender is heavily debated in modern-day India. With my current work experience at the Academy of World Religions, I think that if we look at the issue across various religions, it becomes clear very quickly: we must always differentiate between the ideals of individual religions – how they are being described in religious texts and lived by the saints – and the social realities of individual countries.

It is a known fact that religions always evolve, which should not be a surprise for Buddhists, who understand that everything is impermanent. In this way, Buddhism has already changed several times due to various cultural influences. But in Asian countries, there is always a very strong hierarchical system, and in such hierarchies, men are always higher than women. That is indeed what Venerable Thubten Chodron talked about earlier, the great fear that societal harmony is at risk when the hierarchy is shifted. But in those countries, democratic processes and modernization have set things in motion and prompted hierarchical shifts. And that triggers fear.

So, the question is, how will it level out? Because when the processes of modernization occur, more conservative segments will naturally form that believe, due to the pressures of modernization or so-called Neo-Colonialism, that everything must be preserved as it is and must not be changed under any circumstances. Issues thus become more rigid. And so that is why I think dialogue is so important.

And the question for which I have yet to find an answer – and maybe someone has an idea of how it can be done, as I am feeling a degree of helplessness – is how we should talk to people who refuse to discuss these topics. We can always engage in dialogue with those who are on our side and who think discussion is good, but we really want those on the other side to come on board. And we should achieve this by listening to and understanding them and taking their arguments seriously. I believe we have been trying this for decades.

The difficult question to answer is how to reach this point where we actually listen to each other and engage in dialogue. And I believe this is the exact problem surrounding the entire conversation around gender – perhaps not gender, but rather the liberation of women. Sylvia, you once said to me that equality can only be bargained for with the opposite sex. But the fact of the matter is, women cannot become independent without having discussions and negotiations with men. We need this partnership between both sides of society.

Thea Mohr: Does this somewhat answer your question?

Audience: I would like to raise another point that I picked up during yesterday’s religious interfaith dialogue. I thought it was really quite nice how important a role education played [in the conversation]. I believe that this also affects the „Geschlechterfrage“ [gender question], to use the German expression. I believe that if education can really be integrated into all levels of society, the thinking of future generations can be influenced.

What makes me a little sad is less the issue of gender equality and more the issue of Buddhism in the West, which was prompted by the comment made by Thubten Chodron, who said that among all the many Western Buddhist teachers she knew, half of them did not believe in rebirth. As a part-time tutor of the raining course ten, I have to say, listening to some of the discussions, that I was quite surprised at the beginning, when the point of having faith in rebirth was raised. I noticed how many doubts exist, even among those who I expected to be well established in Buddhism. I thought: “Well, even though this issue is definitely clear to me, others might not have understood it in the same way.” And I have to say that this will still take some more time.

Thea Mohr: Thank you. I think we will continue on this side.

Audience: I noticed something earlier, when you, Sylvia, spoke about your path in life. You highlighted a problem that I have frequently observed and perhaps even personally faced. You said, “‘I am again responsible for, I don’t know, the kitchen? How do I practice and so on” This contains subtle discrimination. I had the same problem when I was getting my degree and my children were still young – I now have all the time in the world since they have grown up. But you have to take on a certain role: either you are the emancipated woman and fight through it, or if you have children, then you are a “Kampfmutti” [battle-mom] and put your children first: “I request these changes since I have children: this seminar has to be on such and such a date because that is the only time I am free.” Or you quickly hold yourself back because everybody else is annoyed by you.

The ways of life and realities of women, due to their biology, tend to be pushed aside. Women ought to be like men. It has to do with hierarchy and the loss of respect for this demographic of society, which has been maintained [until now]. We all have a mother; half of the population is making sure that things run smoothly at home. And it is worth nothing. Therefore, I find this really shocking. Of course, education is still very important – you don’t stop thinking when you have five children running circles around you. In fact, it’s the exact opposite.

In our museum there hangs a beautiful Hindu painting, which illustrates three women visiting a guru and teaching the child in their arms how to place its hands in prayer. As an [indistinct word] ascetic who always keeps his hands up in the air so that they have become withered, the guru points to the student next to him with withered hands. But the child does not just appear from thin air, but comes into being due to the women, although not entirely. As his Holiness said earlier today, we are in the midst of a complex situation. Venerable Jampa Tsedroen also asked how we should get people to talk to us? I believe we need to remember that we are all in this situation together, which does not work without both men and women.

A harmonious situation can only exist when nobody feels disadvantaged, in this case women. We should keep this dynamic in mind, but I do not know whether anyone is all ears. For nuns, the problem of children and who knows what else does not exist. The ordinary problems of women do not apply to us. This is of course great freedom, and an enormous advantage of being a part of the Sangha. But do nuns, when they talk about women’s rights or gender equality, still comprehend that women in general have to shoulder other problems as well? These are, after all, Buddhist laywomen.

Thea Mohr: Yes, thank you very much. Let’s go back to this side [of the room].

Audience: I really want to ask you a question, Sylvia – if I may call you Sylvia. You have experience with Gestalt Therapy from earlier days. I am a Gestalt Psychotherapist and fortunately, Gestalt Therapy has evolved. We are no longer revolutionaries as in the days when [indistinct word] were against it but more pro-something. I could sympathize with your reaction. I would like to ask you, what is your take on this now? We have roots in Gestalt Therapy, which is also Zen Buddhism. But what disturbs me is – and I got this from the Mister… I cannot say Holiness, it is not my style… I say Dalai Lama, whom I very much respect – that he does not have such a natural attitude towards eroticism as we have in the West and as Gestalt Therapists. And that is what I am missing in Buddhism. Otherwise, I have the utmost respect for him.

I also do not understand why the hair has to go, especially as men and women treasure it so much. So basically I am raising the issue of “Body Image Positivity,” whereby there may be a correlation to men respecting women. What do you think, Sylvia, as you have experience with Gestalt Therapy?

Sylvia Wetzel: Well, that would be a much longer discussion. It is a huge topic, and it contains both Western and Eastern connotations. We do have “body hostility” here as well, and the strong emphasis on the body is also a reaction of longstanding “body aversion.” But for the past twelve years, we have held seminars here in Berlin that address the themes of Buddhism and psychotherapy. We take our time to discuss with male and female psychotherapists from a variety of disciplines. And I find it very beneficial to dive into the details, but to be honest, I cannot address this [question] in three or five minutes.

Audience: But I am pleased that you are actively involved in this field. I believe that it will result in our society and Buddhism moving forward.

Thea Mohr: Yes, I would like to conclude the questions now. Okay, maybe one more.

Audience: Okay, I will keep it short and use keywords. I believe it is important to include another level, a spiritual one. Why can’t the Third Karmapa be a woman? Why can’t the Dalai Lama [immanieren – an uncommon German word for the concept of just inhabiting a body] instead of reincarnate, and then the problem would be solved without us having to wait another twenty years? And why is Maitreya – here in Germany every position need to be spelled out as female as well – why can’t this be a woman? If we look at the letters [in Maitreya], Maria is included. We need to get our head around such things. That is the spiritual level. There are so many women who should remember Tara, who vowed to be reborn in a female body. Why should one have to somehow achieve balance through meditation?

Thea Mohr: Most definitely. Tenzin Palmo, who I believe is relatively well known here, also made vows similar to those of Tara to be reborn in female form – and wants to become enlightened first.

Audience: Let me backtrack a bit with my question. We briefly talked about the growing number of nuns getting geshema degrees. Maybe somebody could say something on how Tibetan women judge this progress, including positive developments at Dolma Ling Nunnery in Dharamsala. Maybe Kelsang Wangmo or Carola could say something, as they are very much involved.

Venerable Kelsang Wangmo: Well, with regards to the geshema, the title for nuns, the first group is indeed in the process of getting their degrees. Originally there were 27 nuns, two of whom did not pass their exams. But as for the rest, they have been taking their exams for the past two years and need two more years to attain the geshe title. Now is the second year for the first group and the first year for the next group. Every year, a group of nuns from various nunneries across India will have an opportunity to get their geshe title. Five or six years ago, we would be amused when someone mentioned the “Nun Geshe” title. Nowadays it’s more like: “Of course, Nun Geshe”.

It has now become quite normal in Dharamsala. And the nun who placed first in the exams this year was from Dolma Ling Nunney, which is near Norbulingka. Yes, a lot is happening in that respect, and Tibetans have become acquainted with nuns receiving the same title as monks. In my opinion, the next step is full ordination. Nuns themselves can say, “Now that we have the geshe title, we want the full ordination.” That is something that has to come primarily from Tibetan women.

Thea Mohr: Thank you. And very quickly, the final three comments.

Audience: Actually I did not have a question. I just wanted to express my sincerest gratitude to you all for your commitment, understanding, and wholeheartedness with which you engage in these issues. I am very grateful for that, as I am convinced that Buddhism cannot survive without women.

You are essential to us because of your clarity of thought and tactfulness. My wife is in her sixth year here at the Tibetan Center and studies Buddhist Philosophy. The very first book I read on Buddhism was a recommendation by Carola Roloff, and because of this I can say for certain, that we cannot do without women. Thank you very much.

Thea Mohr: Thank you.

Audience: May I just chime in on this? I believe that no sangha can be without us female Buddhist practitioners. I am from Monterey, California, and have a small sangha – but the women are so much stronger than the men. Is there actually a sangha where the women are not? That is something that was missing tonight. What can we female Buddhist practitioners do to support you?

Thea Mohr: Yes, that is a good point.

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen: Yes, as I just said, we have this lovely brochure, which was made by Gabriela Frey with plenty of support from various sides. There are also some new brochures out on display about the Sakyadhita International Buddhist Women’s Movement. If you want to focus on women’s issues, then I would recommend that you take a look there and perhaps become a member and meet up with other women.

Today’s discussion was a little more centered around monastics. Karma brought us together to focus more on this subject today. But I think it is very important to reconsider, even with the arrival of the female geshes, that an important part of religion is also the rituals. And when we refer to the ritual handbooks, they often state that those who carry out such rituals are fully ordained monks and nuns, monastics of the highest order.

My concern is that if we stop now, when the geshemas can receive philosophical training but are not allowed to study the monastic rules and receive the complete ordination, they will still be excluded from carrying out rituals. It is similar to the Catholic Church and the sacraments, where some of the female pastor counselors are allowed to preach but not to offer the sacrament. A similar development seems to be taking place in Tibetan Buddhism. Therefore, it is the responsibility of us men and women in the West to consciously point out that we wish to have these points properly addressed. I think this will be very important.

Thea Mohr: Very quickly.

Audience: I have a technical question for Venerable Kelsang Wangmo. How did you manage to move to a foreign country and say, “I will stay here,” and then spend the next 24 years there – especially India, which is not part of the European Union?

Venerable Kelsang Wangmo: There is this expression: “One day at a time.” How do we say it in German? “Einen Tag nach dem anderen.” Of course, I never planned to stay that long in India. If I had this plan from the beginning, I probably would have left after fourteen days. But you get used to a lot – in fact, you get used to everything. It was very beneficial; it opened my mind so that I could see different things and experience different cultures.

After all, not everything is perfect, and you can get by with much less. Over the years this was very helpful for me – to learn a new language, experience a different culture and, of course, see the poverty in India and reflect on how lucky I have been to be born with opportunities to make the very best out of my life.

Audience: I actually meant the bureaucratic hurdles.

Venerable Kelsang Wangmo: Oh… the bureaucratic obstacles. Well, if I have to go to an office, then I have to plan in three days instead of two hours. Everything takes so much longer, but you get used to it. Although Indians can be very bureaucratic, the people are friendly and smiling when you walk into an office. One needs a strong bladder because one will drink a lot of tea, but overall there is so much friendliness and fun to be had.

Audience: It seems very easy to get permanent residency there, no?

Venerable Kelsang Wangmo: Not always. I have to apply for a new visa every five years. Sometimes it is more difficult, while sometimes it is easier – but generally once every five years. I would like to mention another thing: it has to do with the issue of rape, as I just thought of something. It is not specifically related to Buddhism, but it came to mind just now. Recently, the Prime Minister of India gave a talk on India’s Independence Day, where for the first time the Prime Minister of India gave an Independence Day speech on the mistakes of Indians rather than an attack of the Pakistanis.

He said. “It is so embarrassing that so many women are raped in India. Every parent should stop asking their daughters, “What are you doing every evening? Where are you going?” and instead ask their sons, “What are you doing? How are you treating women?” I think this is a large movement. A lot is happening in India, even around issues concerning women. The fact that rape crimes are being made public is another sign of change in India.

Thea Mohr: Thank you again. We have gone a little over the time. Just a quick final statement from Gabriela.

Gabriela Frey: Yes, I just wanted to give a quick reference, because the question “What can be done?” has been asked a number of times. I also have heard remarks that we should translate more [Buddhist] texts.

We have specially launched this website BuddhistWomen.eu for those in Europe, because I have always wanted to share my texts with friends in France. However, because most of them speak French, I would say to them, “Here is a great article, perhaps by Carola.” And I would want to share it with them. Unfortunately, because they also did not know English, I would have to translate it for them.

We have started to collect articles, book recommendations, and other things on this website. It has really grown into a network under the European Buddhist Dachverband. If you have something interesting – perhaps a great text in any language – I encourage you to please send it to us, because this is not just a website “for women by women”, but for everyone. I have many male friends who say, “Man, this is really a great text. You should include it.”

There is a tremendous amount of information on there. We even collect social projects. Slowly but surely, the website has turned into a valuable resource. And the great thing is, you can all contribute. Go and take a look. If you don’t like something or notice a mistake, please let me know. After all, we are all human, have our own jobs, and do this voluntarily. It is not perfect, but we are trying our best. It’s really just a collaboration by friends that all of you can take part in.

Thea Mohr: Let me repeat the website again: it is www.buddhistwomen.eu or www.sakyadhita.org. I assume flyers have been distributed.

Gabriela Frey: I have put some more at the corner of the stage. If they are all gone, they will be at the stall tomorrow.

Thea Mohr: Thank you very much. We would like to thank you for your attention and your contributions. I hope that we managed to provide food for thought with the panel discussion this evening. I will keep it short: we wish you all a wonderful evening and an interesting day tomorrow with lectures by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Good Night!

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.