Refuting a permanent self

02 Commentary on the Awakening Mind

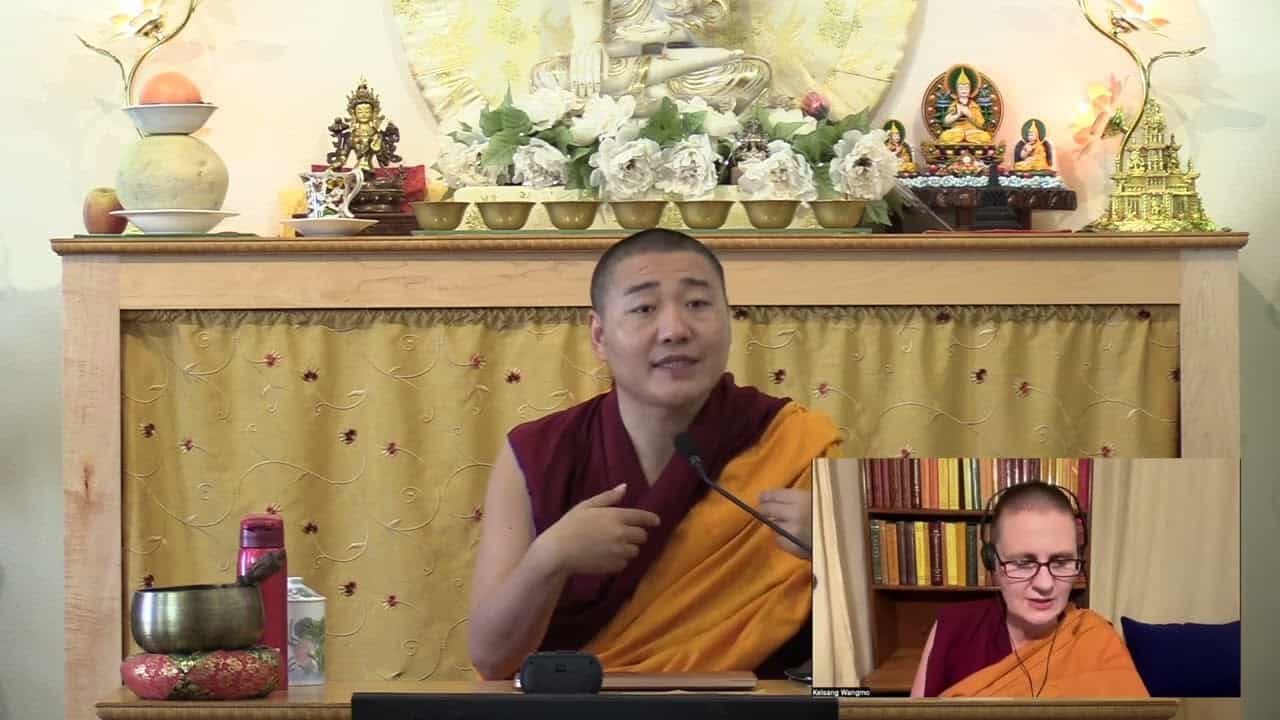

Translated by Geshe Kelsang Wangmo, Yangten Rinpoche explains A Commentary on the Awakening Mind.

Let’s start with the advice of the Buddha: what is the advice that the Buddhas give? When we listen to the Buddha’s advice or we read the Buddha’s advice, what is unique? What is a unique characteristic of the Buddha’s teachings? Well, we aspire to the Dharma. In particular, we aspire to the Buddhadharma. In comparison to those who are not spiritual or who have no spiritual beliefs, there’s a huge difference.

Of those who follow a religion, who have faith, there are those who assert a creator god, and then there are those who don’t accept that there is a self. In that way, there are different kinds of spiritual systems, and this is especially true when it comes to the Buddhist system. We talk about lack of inherent existence; we talk about dependent arising—that phenomena are dependent on each other—and we talk about how all phenomena are merely labeled. So, we belong to this particular Dharmic system or this particular religion that holds all these assertions.

Taking responsibility

As Buddhists, we don’t assert a creator god. It’s said in the scriptures that we are our own protector. Our future is in our own hands. What’s going to happen in the future, whether it’s positive or negative, all depends on our own mind. It’s in our own hands. We have to take personal responsibility. It all depends on us. Based on that understanding then, we should practice. We should practice on the basis of that understanding that we are our own protector.

There are a lot of people who may criticize us and so forth, but it actually doesn’t matter what other people say and think. Sometimes we have this view, like “I may make a mistake. Maybe it’s not okay what I do.” We may have doubts. We don’t really see the virtue of something or the benefits of something, so this kind of doubt arises. We don’t really understand the situation. If we really understand the Dharma well, then when it comes to our future happiness, we understand that we have to work hard for this right now. Therefore, it comes all from our own mind. Our motivation is important. Many of our mistakes come mainly from our afflictions, from our own mind—these different afflictive minds.

These afflictions have existed since beginningless time, so we are used to them. We are familiar with them; we are habituated to them. They are so strong in our mind since they have been with us since beginningless time. Since we have this habit of allowing the afflictions to run wild, therefore it is difficult to make changes. Our attachment controls our mind, and this is not unique to us. This is true for a lot of people. We need to recognize that as a problem, as something that harms us. And if we do that, if we actually recognize the fault of the afflictions, then we are moving towards liberation and Buddhahood.

We make a lot of mistakes because of the afflictions, but this is also true for bodhisattvas. For instance, even on the path of seeing, bodhisattvas make mistakes. Actually, until the forbearance part of the path of preparation, bodhisattvas can still be reborn in the lower realm. So then, of course, all the way up to the seventh ground of a bodhisattva, afflictions may still arise. Only from the eighth ground onward is a bodhisattva liberated. Up to the seventh ground, they still have afflictions. Then once they reach the eighth ground of a bodhisattva, they still have the imprints. The imprints still affect them. Because of the defilement of the afflictions, there are still faults that manifest in the continuum of a bodhisattva.

If we think about that, we should compare ourselves to a bodhisattva in that sense that if even the bodhisattva makes mistakes then we make mistakes as well. There’s no need to be discouraged because the afflictions are not in the nature of our mind. Our mind is clear in knowing. The afflictions are not in the nature of the mind, and therefore, changes are possible. We have a lot of opportunities to change our mind. We have a lot of opportunities to transform the mind. Of course, it depends also on the outer circumstances and our attitude. Our own attitude is really important in this. So, I wanted to share that with you, to stress that again. This will also come up.

As I said earlier, for someone who practices the Dharma, it says you are your own protector. We are our own protector. When we think about a creator god, it’s difficult really to think that there is a creator god. Definitely the view is beneficial for some people. It is a great view from the perspective of how we can benefit others. But from a Buddhist point of view, there is no creator god.

How to subdue our mind

Based on the understanding that we are our own protector, what does that mean that we have to subdue our mind? That is really important. To really find happiness, to find well-being, we need to subdue the mind, to find this inner peace. How do we subdue the mind? Well, we meditate on love and compassion, on bodhicitta, on ethical discipline and so forth. These are all aspirational kinds of mind, but the most beneficial kind of virtuous mind is wisdom. Wisdom is like pouring water on hot iron. Right away the iron cools down. Likewise, wisdom is very effective when it comes to subduing the mind.

For instance, take wisdom analyzing rebirth: based on a lot of reasoning, a lot of analysis, we can come to an understanding that there is rebirth. And this helps us understand cause and effect, to understand that a positive cause gives rise to a positive effect, so the law of karma. And it’s wisdom that helps us to gain certainty with regard to these facts: “Therefore, if there are past and future lives, then there is also karma.” We have to take into consideration the fact that karma has certain actions, and based on that, because of this wisdom and understanding, our actions will change right away. We will adjust our actions based on the law of karma and the concept of rebirth. We need to think about this. We need to apply our wisdom in that way and make changes. We shouldn’t just be obsessed with the sense objects that we perceive around us.

What we see with our eye consciousness, with our ear consciousness and so forth, doesn’t accord with reality. First of all, we don’t hear everything. We hear a few things. We don’t take in all the sounds in the environment. Therefore, we’re very limited in what we actually perceive. It’s the same with the eyes: our eye consciousness doesn’t perceive everything that is around us. Actually, it’s just whatever is in the sphere of vision that we can see. And even with this there are a lot of limits.

So, how should we think? What should our attitude be? Our attitude should be very expansive. Of course we can use our sense consciousnesses, but they’re not totally reliable. Whatever we perceive with them is not most important; most important is our mental consciousness. It’s important to generate a mind that is in accordance with reality, to think in an appropriate way—to use our brain in the right way, to use our mental consciousness to analyze things, to investigate things. Then we can even perceive things that we can’t see with our eyes, and we can’t hear with our ears. We can get a profound understanding of things that we ordinarily don’t know. That is the special attribute, the special characteristic, of our mental consciousness.

Of course, we need to understand the things around us that are obvious, but it’s also important to examine them on a more profound level. It’s like when we say, “For as long as space endures and for as long as sentient beings remain, may I, too, abide to dispel the misery of the world.” It’s important to have this vast view. It’s about this entire life: it’s not important to just be happy in this very life, but in many, many future lives. So, when this verse says, “As long as space endures,” it’s saying that for as long as there is space, we’ll be around. Basically then, this is based on the fact that there’s rebirth. We’re going to be around. We’re really thinking far ahead into the future. It’s not just the immediate future but the long-term future. And in that way, it’s extremely important to focus on the long-term future and what lies ahead of us.

If you only think of the happiness of these 50, 60 or so forth years in this life, or if we think about the happiness of this particular day, does that make sense? That’s too narrow-minded. If we’re only interested in the happiness of right now, if we ignore the future, even if we’re 50 or 60 now, we might live to be 90. Therefore, just as it doesn’t make sense to just be obsessed with the present, we should also think of our future beyond this life. We should think of other sentient beings and so forth; we should take on the personal responsibility also for other sentient beings.

So, this means to actually have joy in our mind that we have this opportunity to work for the benefit of other sentient beings. If we compare ourselves with those who don’t follow religion, they work really hard every day to get a little bit of benefit, so if they get that benefit, they do it joyfully as well. Therefore, if we gain some benefit in the future from working hard, we enjoy doing this. And it’s the same here in the case of Dharma practice. We attain a wonderful result, and we should therefore practice with joy. Of course, there are the essential objects that we do perceive, but we shouldn’t be totally obsessed only with these. Our happiness shouldn’t just be dependent on perceiving these sense objects. That’s not enough. If we’re only interested in the sense objects—beautiful visual objects, nice sounds, delicious tastes and so forth—then we may be in great danger.

Well, the problem with having that attachment to these objects is that as long as we have these objects, we’re okay, but maybe at some point there aren’t any beautiful visual forms, there are no nice sounds and so forth. Then we have a problem. The thing is that the sense objects are impermanent, so they keep changing; they keep disappearing. Therefore, the happiness that comes from our own mental consciousness, that is important. The happiness that rises from our mental consciousness, from our conceptual mind and so forth, doesn’t depend on external circumstances because happiness comes from within. That’s very important advice.

If we practice, study and train in the Dharma then we will get a kind of a real taste of the Dharma. This is practical. On a practical level, this is very helpful. We can change on the basis of our own thoughts, on the basis of our own analysis. Of course there are beautiful aspects outside in the external environment, but even beautiful aspects can harm us. They have beneficial and harmful aspects. Therefore, it’s not the case that the external environment, the sense objects, always bring us happiness. They also have disadvantages. It’s so important to really understand the situation.

If the external situation is positive or not, it doesn’t matter. We should be accepting of whatever happens; we should be satisfied with whatever happens. What is most important is our wisdom, our concentration: the mind that wants to benefit other sentient beings. So, this kind of very expansive attitude is important. We shouldn’t be narrow-minded. When we talk about being content with little, we’re not trying to force it at all. We’re talking about generating true satisfaction. Being content with little means that we are satisfied even if we only have a few things. If we don’t have the things that we don’t necessarily need, that’s okay. We need to understand that since certain objects aren’t essential then it’s okay if we don’t have them. This means understanding that all of these objects that we usually desire are not necessary.

It’s a voluntary kind of process where from your own side, you agree to just let it be, and it gives us a kind of freedom. It’s not forced. Therefore, it’s important to control our desire, to not always have desire for things that are not needed. In that way, if we really strengthen our thoughts, our mental consciousness, it’s extremely beneficial. And also, when it comes to mental qualities, no one can steal them from us. No one can steal our positive qualities, our positive characteristics. When we study, reflect and meditate on the Dharma and develop certain attainments, certain insights, in dependence on that, no one can take them away from us. Of course, external objects can be stolen from us. A thief could rob us of these objects. We could also lose our friends and our relatives. Some people may not even like to give something to us. Therefore, this dependence on external objects is a problem. So, I wanted to stress this again, that our inner qualities are so much more important.

Refuting wrong views

So, now we will go to verse number two:

The Buddhas maintain the awakening mind

To be not obscured by such conceptions

As consciousness of “self,” “aggregates,” and so on;

It is always characterized by emptiness.

So here, Buddha Shakyamuni and all the other buddhas, what are they saying? They maintain that the awakening mind—the wisdom body of a Buddha—is not obscured by such conceptions as consciousness of self, aggregates and so forth. “The self or the aggregates” includes, for instance, the very subtle particles; there are no partless particles and so forth. It’s free from such conceptions. For instance, the Cittamatras say that there are no external phenomena, that there are no truly existent external phenomena. There’s only a truly existent mind. But this kind of view is actually not okay. Actually, the Buddha’s maintain that it’s not obscured by such conceptions as consciousness of self, aggregates and so forth, but it’s obscured by such conceptions of truly existent external phenomena.

Now, with regard to the wisdom body of a Buddha, or the wisdom nirmanakaya of a Buddha,, this is free from all obstructions. This is free from all obstructions now. It’s not in the nature of the mind, but it’s also completely free from all temporary kinds of afflictions, and of course, of the natural kind of obstructions as well. It’s totally free from those.

Then verse three says:

It is with a mind moistened by compassion

That you must cultivate [awakening mind] with effort.

The Buddhas who embody great compassion

Constantly develop this awakening mind.

So, we need a mind that is moistened by compassion. It needs to be controlled by compassion. Therefore, our actions should always be controlled by our compassion. Bodhichitta here should be conjoined with compassion so that we always work for the benefit of sentient beings that are always influenced by this compassion. So, this goes back to that aspiration we discussed earlier: “May I save those who are not saved; may I liberate those who are not liberated; and so forth.” It’s this kind of mind of bodhichitta, of compassion. Here we are talking mainly about conventional bodhichitta. Conventional bodhichitta is the mind that should always be moistened by compassion. And then verse number four refutes the view of the non-Buddhist philosophers when it says:

The self postulated by the extremists,

When you thoroughly analyze it with reasoning,

Within all the aggregates [of body and mind],

Nowhere can you find a locus for this.

Now, when we talk about the self, we’re always totally obsessed about the self. We’re always thinking about the self. The self is the center of our universe. It seems like of all the different existences, the self is the center. So, we are the center of the universe. We are the center of everything. Whatever we do, the self is involved: “What happens to me? What am I doing?” And so forth. In every moment, whatever we do, the thought of “I am” is just always present. Therefore, it’s so important to really reflect on the self. That which wishes to be happy is the self. That which doesn’t want to be unhappy is the self. When we say that there’s happiness, it’s the self that is happy. And when there’s suffering, what suffers is the self. The self is that which wants to be free from suffering.

What we really wish for is happiness; what we really don’t want is suffering. So, what is the main cause of happiness and suffering? It’s important to recognize where happiness comes from and where suffering comes from. The main cause is the self. Usually, there’s a sense that it’s the self that brings us happiness. Therefore, we think the self is so important. And the non-Buddhist systems talk a lot about the self. They describe a self; they present a particular self. And on that basis, they explain that happiness is the self. Then they explain happiness and suffering. Therefore, we need to analyze, does that self exist or not?

When the Buddha talks about liberation, karma and so forth, if there is no self, then from a non-Buddhist point of view that becomes imbalanced. That’s why it’s important to analyze this. Of course, it’s not okay to force someone not to talk about certain things. It’s not about forcing other people to assert what we assert. But we need to analyze, “What is reality? Does it accord with reality or not?” We need to understand the way the self is presented by the non-Buddhist philosophers and question whether it is in accordance with reality or not. That’s important. And this is what Nagarjuna says here in verse four:

The self postulated by the extremists,

When you thoroughly analyze it with reasoning,

Within all the aggregates [of body and mind],

Nowhere can you find a locus for this.

So, what is the self that the non-Buddhists assert? It’s a partless, independent self. Most of the non-Buddhist philosophers assert such a permanent, partless, independent self. It’s a self that is permanent, that is partless and independent. What does it mean to have a permanent self, a self that does not change moment by moment? Here, when we say partless, it means it doesn’t have any parts. It doesn’t exist of anything other than itself. That’s what it says in Blaze of Reason, for instance, by Bhavaviveka. He explains the meaning of a permanent, partless, independent self.

When we say independent here, it means that the self is not dependent on causes and conditions. That’s why we say it’s independent. Such a self is what’s being asserted: a self that is permanent, partless, and independent. But when we check where does this self exist within our aggregates, well, we can’t find it. If such a permanent, partless, independent self did really exist then it needs to exist somewhere. We need to be able to point at the basis on which it exists. But we can’t point at such a self. There’s nothing to point at. But if it existed, we should be able to find it.

And then this goes on in verse 5:

Aggregates exist [but] are not permanent;

They do not have the nature of selfhood.

A permanent and an impermanent cannot

Exist as the support and the supported.

As I said before, this is refuting the non-Buddhist philosophers. Of course the aggregates exist. But all philosophical Buddhist schools, except for the Madhyamaka system, believe that the aggregates exist substantially—that there’s something that we can find. They believe that there’s something findable from the side of the aggregates. The aggregates exist, but they’re not permanent. So, the self that the non-Buddhists assert is permanent. But there is no self that can be asserted with regard to the aggregates because the aggregates are not permanent. We also can’t say that the aggregates are the self because we say the aggregates are owned by the self. We say my aggregates. Therefore, the aggregates and the self are separate.

When I say my body, when I say my feelings and so forth, it implies there’s an owner. The aggregates are of the self, so the self is like the owner of the aggregates. The aggregates are that which is owned, and it cannot be the same as the self. The aggregates and the self cannot be separate. So, they do not have the nature of self, but a permanent and impermanent cannot exist as the support and the supporter. What does that mean? We cannot have one being the support and the other one being the supporter—one being the basis and the other one being based on that. If one is permanent and the other is impermanent, it doesn’t make sense.

If the aggregates are impermanent and the self is permanent, it doesn’t make sense to have that relationship of one being the support and the other one being the supporter. That’s contradictory. If the aggregates are impermanent, how can the self then that serves as their basis be permanent? That would not make sense. If the self is based on or dependent on the aggregates, then how are they related? Are they of one nature, or is there another way in which they are connected? Here, support and supported is actually a relationship of being of one nature. But if that’s the case, they cannot be different in terms of one being permanent and impermanent.

Then verse number six says:

If the so-called self does exist,

How can the so-called agent be permanent?

If there were things then one could

Investigate their attributes in the world.

If you say that there’s a self that is permanent, partless, independent—a substantially existent self—that’s not possible. Such a self logically doesn’t make sense. It cannot be positive. If such a self doesn’t exist substantially, if it cannot be found, then how can it be an agent? We talk about a self as the one that does things. So, it’s that which is reborn in samsara or that which is cycled in samsara, that which is liberated. It’s that kind of self. That’s the kind of agent. We talk about an agent as someone that does something: the one that generates or accumulates karma, the one that experiences happiness or suffering. So actually, it doesn’t make sense that the self that is permanent is such an agent or does such things—accumulates karma, for instance, or experiences the karmic effects—because it has to be impermanent.

It’s not possible that those experiencing entities, since they change, are permanent. An agent has to be impermanent. Something that performs an action has to be impermanent. So, this view says the self is the agent—that which experiences suffering, that which experiences happiness and so forth—but this self is that which cycles in samsara. It’s that which is liberated. That is one characteristic of this self. If that is the case then the self has to be impermanent. Otherwise, this view doesn’t make any sense. It’s impossible. It’s impossible for a permanent self to experience anything. So, you need to understand this. You need to investigate that. Because if there were things then one could investigate their attributes in the world. If there is a basis, if there’s something like some base that we assert, then we have to talk about certain characteristics. For instance, consider this table: there are certain characteristics that this table has. We can put things on top of it. We can put our phone on it. We can put our computer on it. It performs certain functions. It has certain attributes. And on the basis of that object, we can talk about these attributes.

Since it’s impossible for the self to experience suffering and so forth, you can’t talk about someone who experiences suffering and happiness and so forth. If there’s no experiencer, that doesn’t make sense. So basically, if the self is permanent, experience and so forth doesn’t make sense. When we talk about a basis that has certain characteristics, it’s only possible for the characteristics to exist if the basis is there.

And then verse 7 says:

Since a permanent cannot function [to cause]

In gradual or instantaneous terms,

So both without and within,

No such permanent entity exists.

We can say that the self experiences happiness. It’s the common locus of that which experiences suffering and happiness and so forth. It’s that which accumulates karma. There’s no contradiction that there’s one basis that does all these things, that experiences these things and so forth. Here we’re talking about non-Buddhist philosophers who existed at the time of the Buddha, so the Sravakas, for instance. They actually don’t say that the self is the agent, but they do say that the self experiences happiness and suffering. A permanent cannot function to cause in gradual or instantaneous terms, so both without and within no such permanent entity exists. Whether external or internal, no permanent, independent kind of self can be found. Why? Because in gradual or instantaneous terms, it’s impossible.

The non-Buddhist philosophers talk about this self that does certain things, that experiences. In many philosophical systems they do assert that. So, there are a lot of non-Buddhist systems that actually assert such a self. They assert such a self that is like an agent, but it doesn’t make sense because a self that is permanent cannot affect our experiences. It cannot affect phenomena. It cannot be a cause of something. Because if a self does bring forth a result, either simultaneously or progressively, then first you have the cause, which is the self, and then a result arises. It’s impossible, though, that the self can actually give rise to an effect simultaneously. That doesn’t make sense. First there’s the cause, and then there’s the result.

For instance, if we accumulate virtue in this life then in the future we experience happiness. Of course we assert that the self accumulates karma, but if the self were to be permanent, how could it have a karmic effect? It wouldn’t make sense. And if it were hypothetically the case that it happened simultaneously then cause and effect would exist at the same time, and that doesn’t make sense. If I accumulated positive karma, I would right away experience the positive result of that, which doesn’t make any sense. But if it happens gradually then again, that doesn’t make sense. Why? Because the self is permanent. So, if the self accumulates negative karma and then in the next life the result is experienced, it doesn’t make sense because then the cause would still have to exist at the time of the result. Why? Because the self is permanent. It doesn’t change. If it’s a cause now, it must be a cause in the future. It must be a cause at the time when this result comes into existence.

Therefore, with the self being the main cause, it doesn’t make sense that it gives rise to a result gradually either. Why? What is the reason for doing so? It exists at the time of its result because it’s unchanging. It’s always a cause. So with the self being a cause, with the self being permanent then even in the future when the result ripens, the cause has to be there as well. The self has to be there as well because it is permanent. When we talk about cause and effect, if they’re both existing at the same time, that doesn’t make sense. Therefore, why do we not have a result right now? It’s because all the causes are not there yet, because they’re not complete. That’s what it says in the Pramanavarttika, for instance.

If not all the causes and conditions are there, you don’t have the result. Why does a result not ripen? It’s because some causes and conditions are missing. But if the cause is always there then actually, cause and effect have to ripen instantaneously. If there’s a permanent, partless, independent self, it doesn’t make sense because cause and effect would have to exist at the same time. Therefore, there is no self. There’s not a self externally nor internally. There’s no self that can be found.

Refuting a permanent self

Then verse 8 says:

If it were potent why would it be dependent?

For it would bring forth [everything] at once.

That which depends upon something else

Is neither eternal nor potent.

This is another kind of analysis. If something is permanent, can it give rise to an effect? Does it have the potential to propel an effect or not? If it did, it wouldn’t need any other conditions. This is the same kind of analysis that you apply when refuting a creator god. If there’s a permanent cause that gives rise to an effect—like a creator god or a permanent self—then giving rise to the effect, it wouldn’t be dependent on anything other than itself. If it had to depend on something else then we wouldn’t say it’s a creator. We wouldn’t say it is that entity that in itself could create a result if it depended on other causes and conditions. So, does it give rise to an effect gradually or instantaneously? Well, it actually doesn’t make sense because the question that arises is, “Does it depend on something else or not? Does it not have the potential to give rise to an effect?”

If it does have the potential to fully give rise to an effect, you don’t need other phenomena. But if it doesn’t have the potential to give rise to an effect in itself, then it cannot be that main cause. In that case, it would bring forth everything at once. That which depends upon something else is neither eternal nor potent, as it says here. So, it would be able to at once bring forth everything at the same time; all effects would arise immediately. Everything at once would arise. This verse says that that which depends upon something else is neither eternal nor potent, so if it were to depend on something else, it would have to change itself. It would slowly change in dependence on other factors, and then it would give rise to an effect.

For instance, it’s like a seed: when you plant a seed, the seed is changing, changing. You add the other conditions, such as water and so forth, and through that slow, gradual change then a sprout arises. Therefore, when it comes to the self, it doesn’t make any sense to say it’s permanent, and it gives rise to all these different effects. It doesn’t make sense. It’s much better to say that the self is impermanent. Why do you insist that the self is permanent? There’s no need to say so. As Nagarjuna argues here, it doesn’t make any sense to say it’s permanent. Just as we say other things are impermanent, what’s the problem with saying that the self is impermanent, that it’s dependent on other causes and conditions, that it depends on other factors and changes? Such a phenomenon must be impermanent. If it depends on other things, then it’s constantly changing. Therefore, it doesn’t make sense.

Then verse 9 says:

If it were an entity it would not be permanent

For entities are always momentary;

And with respect to impermanent entities,

Agency has not been negated.

So, this is the last verse that refutes the non-Buddhist philosophical Indian systems. If this self that you assert to be permanent, partless and so forth were an entity, it would not be permanent. This particular entity wouldn’t be permanent because entities are always momentary. We talk about entities as something that performs some function. So, when we say entity, it refers to different kinds of things. External things, like possessions that we have, the things we own, are described as entities. It’s something that exists by way of its own character. It’s something that performs a function that can be perceived without sense consciousness. If the self were such an entity, it would not be permanent because entities are always momentary. They’re always changing. They’re momentary in the sense that they constantly change.

How do entities exist? They have to exist in a way that it has this particular characteristic that it shares with other entities. So, if the self were an entity, it would have to change all the time; it would have to be impermanent. With respect to impermanent entities, agency has not been negated. Therefore, entities would always be changing. With respect to impermanent entities, agency has not been negated. What does that mean? When we talk about impermanent entities, impermanent things, first of all, it’s impossible for an impermanent entity to be permanent. For that reason, if it’s impermanent then we can say it’s an agent. We can say it performs a function. It does things. If something is permanent, it cannot do things. But if it is impermanent, agency is possible. So, it has not been negated. Something that is impermanent can be an agent; agency is possible. This is discussed a lot in the Pramanavartiika: it’s impossible to have a cause that is permanent with a result that is impermanent, or a result that is permanent and a cause that is impermanent. That’s impossible. It doesn’t work at all. Cause and effect have to both be impermanent. If the cause is impermanent, the result has to be impermanent. Otherwise, if the cause is permanent and then all its results are impermanent, that is contradictory. It doesn’t work. This is what it’s saying here.

Analyzing the aggregates

And then verse 10 says:

This world devoid of self and so on

Is utterly vanquished by the notions

Of aggregates, elements and the sense-fields,

And that of object and subject.

Here, when it says, “Aggregates, elements and the sense fields, and that of object and subject,” we’re talking about the five aggregates mainly. Basically, all phenomena can be included in the five aggregates. Physical objects are the form aggregate—the things we can see with our eye consciousness, what we can hear with our ear consciousness. In other words, it’s the different sense objects that we experience on a daily basis, the objects we can enjoy on a daily basis. That includes also our own body as the basis on which we can experience, we can utilize, other physical objects. It’s kind of the basis for our mental consciousness, for instance. So, what is the physical basis? It’s a collection of many atoms. Here, it’s utterly vanquished by wisdom. The wisdom vanquishes this notion, or the wisdom vanquishes aggregates and so forth.

Then verse 11 says:

[Thus the Buddhas] who seek to help others

Have taught to the disciples

The five aggregates: form, feelings, perception,

Volitional forces and consciousness.

The most extensive explanation you find of the aggregates is in the Abhidharmakosa, The Treasury of Knowledge, by Vasubandhu. It describes the different meanings of each of these aggregates, so it’s important. We’re not saying that there are six aggregates. We’re not saying there are three aggregates. Why are we talking about five aggregates? The first chapter of the Abhidharmakosa describes the five aggregates especially well. If you can read this text, it’s very helpful. It’s also in the higher Abhidharma from Asanga. There you can also read about this—in the companion to the Abhidharma. You find that also in Asanga’s text.

Anyway, form is that which is suitable to be physical in the sense that it’s obstructive. You can touch it and so forth. It’s something you can touch, something that can obstruct. When you move your hand and come close to a wall, you won’t be able to move your hand through the wall because it is obstructed. Of course there are some very subtle forms that are not obstructive, which is slightly different. There are different types of form. Touching and obstructing is different, but in general, there’s no obstruction. So, there are physical objects: objects that are kind of solid. When they appear to our mind, they appear as physical objects to the mind, as material objects to the mind. That’s why we say it’s suitable to be physical. That’s the definition of form.

Then feeling refers to pleasant, unpleasant and neutral feelings. This means feeling happy, feeling pleased, feeling unhappy. And then there’s perception—being able to perceive this is this. This is a vase. This is a pillar. This is the size of the vase. This pillar is kind of long. It supports other objects; it supports a beam and so forth. That which is able to distinguish between this is called perception or discernment. And then there’s volition or the volitional forces. We usually speak of 51 mental factors; the Abhidharmakosha talks of more than 40 mental factors. When we say volitional forces, they all are included. They are all compositional factors. There are all these different mental factors, and they’re all included in this.

And then there’s consciousness. The Buddha is such an expert when it comes to teaching the Dharma. So, why did he talk about the five aggregates? Everything the Buddha said, there’s always a reason for it. The Buddha, when he talks, when he gives teachings, his teachings are so profound. He has this special ability to give teachings. By teaching the five aggregates, the Buddha actually also implied selflessness. By describing the five aggregates, implied in that is selflessness. Why? Because when you talk about five aggregates of a person, it becomes obvious that there’s no self. You have the form aggregate; you have the feeling aggregate; you have the aggregate of feeling; you have the aggregate of perception; you have the aggregate of the compositional factor; and you have the aggregate of consciousness. The five aggregates are that which the self owns, basically. It’s that of which the self is the owner.

We say my form, my feelings, my intelligence, and so forth. My intelligence, for instance, is part of the compositional factor. When it comes to feelings, we say, “I’m happy; I’m not happy.” So, our feelings are seen to be owned. We usually understand our feelings to be part of the self, as in the self owning them. Basically, when we say the five aggregates, there’s no sixth aggregate. It’s better to say that all impermanent phenomena are included in the five aggregates. It doesn’t really apply to permanent phenomena; therefore, we usually say that all impermanent phenomena are included in the five aggregates. They’re one of the five aggregates.

So, basically, when we talk about the five aggregates, there’s no self that can be found as existing separately. We have form, feeling, perception, etc., but no separate self. So, on the basis of understanding these five aspects, we understand that there’s no self. Some phenomena are part of form. Some impermanent phenomena are part of feeling. Some impermanent phenomena are part of perception. Some are part of the compositional factor and some of consciousness. But there’s no self left. There’s no separate self that is not included in any of the five. Therefore, the Buddha implies selflessness in this teaching.

The aggregates are illusory

Then in verses 12 and 13, it says:

The excellent among the bi-peds

Always taught as well “Forms appear as mass of foams;

Feelings resemble bubbles in water;

And perception is like a mirage;Mental formations are like the plantain trees;

consciousness is like a magical illusion.”

Presenting the aggregates in this manner,

[The Buddhas] taught thus to the bodhisattvas.

A biped is someone who is a living being who has two legs, so that’s a human being. Most other living beings have four legs. Are there beings who have two legs? Well, birds have two legs but no arms. The Tibetan word used here is two-legged, referring to humans. In the second chapter of the Pramanavattika, it uses a term meaning the one who has an arm. That’s actually another word for an elephant. Actually, it’s probably from the Sanskrit. Another term for an elephant is like the one who possesses an arm. Similarly, this term for two-legged probably developed according to a certain environment or certain time and so forth. So, the excellent among the bipeds—the excellent among the humans—always taught that forms appear as masses of foams. Feelings resemble bubbles in water and perception is like a mirage. Mental formations are like the plantain trees. Consciousness is like a magical illusion and so forth. So here, the Buddha is teaching selflessness to the bodhisattvas.

You understand a mirage, right? In the summer or in the autumn, when the sun hits sand, it creates the illusion of water. Some of the wild animals believe there’s water, so they walk towards this mirage because they actually perceive water. So, perception is like a mirage. Similarly, mental formations are like plantain trees. Some say it’s a banana tree, but there are also other kinds of plantain trees. These trees have no essence. When you take the stem, for instance, you can actually remove all these different layers of it, but there’s no kind of essence to it. You can just continue removing all these different layers and never find something concrete in the center. That’s why it’s used here as an analogy.

Then consciousness is like a magical illusion, which is talking about a magician or the magical apparition. They use these mantras and special substances to conjure—from like a pebble and wood, they’re able to conjure like a horse and an elephant. These are magical apparitions. That has to do with the mantra they recite and external substances that affect our eyes. On the basis of that, these illusory appearances arise. So, the Buddha taught that to the Bodhisattvas. Phenomena do not exist inherently. They do not exist in and of themselves, but they are like these illusions. They’re like dreams. They’re like these magic apparitions of a horse and an elephant.

Then verse 14 says:

That which is characterized by the four great elements

Is clearly taught to be the aggregate of form.

The rest are invariably established

Therefore as devoid of material form.

They’re not material; they’re not physical. Without the form, certain things cannot arise. Without having material objects, without having the great elements, you couldn’t have the form aggregate. This is what this verse explains.

Then verse 15 says:

Through this the eyes, visible forms and so forth,

Which are described as the elements,

These should be known also as [the twelve] sense-fields,

And as the objects and the subjects as well.

In the Vaibhasika and the Sautantrika school, they talk about objects existing as truly externally existent. They arise as a result of many atoms, and so forth. So here it says that these should be known also as the 12 sense fields. So, these are the sense fields: the six objects and the six sense powers.

Refuting partless particles

Then verse 16 says:

Neither atom of form exists nor is sense organ elsewhere;

Even more no sense organ as agent exists;

So the producer and the produced

Are utterly unsuited for production.

The main meaning of this is that there are no coarse objects that arise as a result of partless particles. Partless particles, or partless atoms, which some of the lower Buddhist schools assert, are refuted here. It’s talking about the different objects, the six elements—form, visual form, sound, smell, and so forth. So, for instance, when we see the color blue, we see a coarse object that’s blue. When it says “Neither atom of form exists nor is sense organ elsewhere,” it basically means that this coarse object which is blue is not made of partless atoms. It’s not a coarse object that is made of partless atoms because there are no partless atoms. Even more, no sense organ as agent exists. It’s impossible that this sense organ itself serves as agent. You need external objects as well. Therefore, the producer and the produced are utterly unsuited for production.

Then verse 17 goes on to say:

The atoms of form do not produce sense perceptions,

For they transcend the realm of the senses.

[If asserted] that they are produced through aggregation,

[Production through[ collection too is not accepted.

How does an eye consciousness arise, for instance? The very subtle atoms do not produce sense perceptions to the sense because the subtle atoms do not appear or they’re not perceived. They’re not perceived by our sense perception, but they transcend the realm of the senses. So, there’s not something we can perceive. If asserted that they’re produced through aggregation, that all these atoms come together, even that is not possible because here we’re still talking about partless atoms. It’s impossible for partless particles or partless atoms to aggregate. What does it mean to aggregate? Oftentimes we say an aggregation is something coarse, something that is made of many parts. So, just talking about the parts, like if we talk about partless particles, it’s impossible that partless particles or partless atoms serve as a cause for the sense perception, because they can’t be an aggregation.

If you think about partless atoms aggregating it doesn’t make sense, because there’s no relation between them, because they cannot aggregate. They cannot aggregate to become more than just one particular atom because when you remove all the aggregation, you would still have partless particles. So, when we talk about physical objects, such as wheels and different machines and so forth, when we actually remove its parts, there’s nothing left. In reality, there’s nothing left. You can continuously divide it up, and you’ll never find anything. But if there’s a partless particle then you always find something very solid that is left, and that cannot be part of the aggregation. It actually doesn’t make sense. This is the kind of logic applied here.

And then verse 18 says:

Through division in terms of spatial dimensions

Even the atom is seen as possessing parts;

That which is analyzed in terms of parts,

How can it logically be [an indivisible] atom?

It’s impossible to have some aggregation that is a result of many partless atoms. Even the Cittamatra school doesn’t assert that. The Madhyamaka school doesn’t assert that, and the Cittamatra school doesn’t assert that. When we say partless, it’s impossible that it aggregates. There’s a contradiction in terminology. If it’s partless, how can it aggregate with other objects? So the Cittamatra and Madhyamaka school would say that’s a contradiction in terminology. If it’s partless, it will always remain the same. If it comes together with other objects, it will never become bigger. The other verses explain exactly this point. If there were physical objects that come together as a result of partless atoms, that would be impossible. Why? Because they couldn’t aggregate. Partless atoms cannot aggregate in that one is the part possessor of these atoms. That just wouldn’t make sense, because that would mean that if we remove all these different parts of the aggregation, we would be left with something very solid that has nothing to do with the aggregation. So, this would be contradictory.

When we have many then it’s possible to have many particles come together to form an aggregation, to form many objects, to form a coarse phenomenon. That is possible. For instance, with the objects all around us, basically they’re aggregations of many subtle particles. One is the part possessor, and one is the part. We talk about the object that is formed by the many parts as the part possessor, and then there are all these parts. There’s a whole and there are parts. But if something is partless, it cannot form a whole. It cannot form an aggregation or a whole. Why? Because partless particles cannot become bigger. They cannot come together with other objects to become bigger.

So, does it make sense to you that if there’s a partless particle, it cannot aggregate with other things to become bigger? It’s partless. If it’s partless, then it doesn’t matter how many partless particles come together. Nothing big could arise from them. And it’s not just that. Why? Because you’re saying that this view of partlessness doesn’t make any sense. You’re saying that through division in terms of spatial dimensions, even the atom is seen as possessing parts. It has to have parts. An atom is made of parts other than itself—for instance, the directional parts: parts that are part of the southern direction, the northern direction. In that way, they occupy a space. They exist as having different sides and so forth. Therefore, it’s impossible that they are partless.

Then verse 19 applies more reasoning when it comes to the Cittamatra or the Madhyamaka school:

With respect to a single external object

Divergent perceptions can arise.

A form that is beautiful to someone,

For someone else it is something else.

Again, this is the view of the Cittamatra or the Madhyamaka. When we say something is beautiful or something is ugly, something is attractive or is unattractive, it’s the result. If it’s an external object—the result of partless atoms—then we say it’s beautiful because these different kinds of atoms come about. Or based on that, we say it’s ugly. This is talking about being able to say something is nice, good or bad according to this particular view that there are partless particles. If that were really the case, it actually wouldn’t make any sense. Why? There are actually different perceptions of this external kind of object. So, it wouldn’t make sense that there are these partless particles in the sense that you have different perceptions of it.

One object can be perceived in different ways. A form that is beautiful to someone, for someone else, it is different. It’s dependent on a person. For some person, this is attractive. For another person, it’s unattractive. One object can be seen in many different ways. Why? Verse 20 gives us an example:

With respect to the same female body,

Three different notions are entertained

By the ascetic, the lustful and a [wild] dog,

As a corpse, an object of lust, or food.

With one female body, three different notions are entertained by an ascetic, the lustful, and a wild dog; it is perceived as a corpse, an object of lust, or food. But it’s just one object, one particular: a female body. From the point of view of an ascetic, it’s a corpse. Even though a person is still alive, for an ascetic it’s just this body that’s walking around. It’s kind of like a corpse. And then for a lustful person, the female body is seen as an object of lust while a wild, hungry dog perceives this particular human body as food. Wild animals, like a tiger and so forth, would perceive this female body to be food. There are different perceptions based on three different beings. Therefore, if it was really from the side of the object—if there was a concrete object over there, a partless particle, something concrete coming from the side of the object—then it would be impossible to have these three perceptions.

Everyone would perceive it in the same way because from this view of partless particles, that attractiveness is from the side of the object. It depends on the object itself. Everything comes from the object. It comes from this object, this material, physical object over there that is the result of many partless particles coming together. If it existed solidly in and of itself, there couldn’t be different perceptions. Everyone would have to see this object as in the same way. For example, it should be an object of lust for everyone. Even a person who doesn’t have any attachment would still consider this female body to be an object of lust. Or everyone would perceive it as food instead. As another example, let’s say the woman has died. In that case, the woman is actually a corpse, so just like a wolf views it as food, so everyone should view it. In this view, because it exists in and of itself as such, and it’s made of partless particles or partless atoms, it exists in and of itself.

What is this attractiveness from the point of view of the Vaibhasika and the Sautrantika schools? They would say that this beauty comes from the side of the object. It exists in and of itself. It’s this coarse object that is the result of the aggregation of partless atoms. On the basis of that, then beauty and so forth arises. Since it exists in and of itself, there can’t be different perceptions.

For example, consider a body of water, like the Ganges, as it is perceived by a human, a preta being or a hungry ghost. When a human looks at it, they see water. A hungry ghost would see it as empty, like a desert. And a celestial being would perceive this as nectar.

It’s the same object—liquid—but dependent on the different beings, it’s perceived in a different way. If it were actually an aggregation of partless atoms, it would be impossible for these different perceptions. This is what this is saying here. This is a very potent kind of reasoning, isn’t it? It’s a sharp kind of reasoning, and doesn’t it make sense, actually? When we see a body of water, we actually see water. But a hungry ghost perceives pus and blood. Celestial beings perceive nectar. But we don’t know that; this is hidden for us. We can only understand this on the basis of the scriptures.

Let’s take another example: say there are three people looking at flowers in a flower garden. So, we have three people looking at the same flowers. They’re just beautiful flowers with this really nice smell, and so forth. But actually, everyone has a different experience of these different objects. In terms of whether the objects benefit us or harm us, we have a slightly different view. We have a different view when it comes to the different objects we perceive, even if we look at the same object. Even though two people might have similar bodies, similar diseases and similar attitudes, there’s still a difference. For instance, when you take medicine, although we are quite similar, we all have a different experience. There’s a different smell, for example. There’s a different experience. When we perceive things, it’s different. Based on that understanding, we all perceive things slightly differently. We can get a sense of what is said here.

Everything comes from the mind

Then verse 21 says:

“It’s the sameness of the object that functions,” [if asserted],

Is this not like being harmed in a dream?

Between the dream and wakeful state there is no difference

Insofar as the functioning of things is concerned.

Some would argue that when it comes to partless atoms, it’s the same. It depends on the person. For instance, in the Cittamatra school, they say it’s based on the ripening of imprints. In the Madhyamaka school, we say that it has to do with the person. So basically, the Cittamatra and the Madhyamaka school would say that there’s nothing from the side of the object, whether it’s because there’s no external phenomena, or whether the reason is that phenomena doesn’t exist externally, or whether it’s because everything comes from the mind. In both cases, nothing comes from the side of an external, truly existent object.

We have so many different imprints, for instance. Everyone has left different imprints. There are so many different types of imprints, and because of the imprints, we perceive things differently. Therefore, we have different habits; we’re familiar with different objects. Our habits, our imprints, very much affect our mind. Therefore, we perceive different things. We have different appearances. This is what this verse is saying here. When it says, “It’s the sameness of the object that functions…is this not like being harmed in a dream,” it basically means that the objects that we perceive don’t exist in and of themselves. That doesn’t make sense. Whether we see a beautiful object in a dream or while we are awake, it doesn’t matter. None of the objects that appear to us are the result of these particles. So, the dream and the wakeful state are the same insofar as the functioning thing is concerned.

Then verse 22 says:

In terms of objects and subjects,

Whatever appears to the consciousness,

Apart from the cognitions themselves,

No external objects exist anywhere.

When it comes to subject and object, there are no truly existent external objects. In the Cittamatra school, it’s because of the imprints, basically. Due to the imprints, objects appear. So, phenomena appear to exist externally, but they don’t exist in actuality. It’s just because of the imprints. The Cittamatra school would argue that these appearances arise in our mind, but they don’t appear because they’re partless particles that have come together. Again, if they were really partless particles, then we wouldn’t have different perceptions. You wouldn’t have a preta being that perceives liquid to be blood. You wouldn’t have a human that perceives it as water, and so forth. That would be impossible. Therefore, apart from cognitions themselves, no external objects exist.

Then verse 23 says:

So there are no external objects at all

Existing in the mode of entities.

The very perceptions of the individual consciousnesses

Arise as appearances of the forms.

This is the Cittamatra view. They say there are no external objects at all. Whatever appears—forms, sounds, and so forth—just arise as appearances. So, for example, perceiving something as beautiful is because of the appearance to our own mind as beautiful. It’s just an appearance. And that’s individually different. It’s not the same for everyone, because we all have different minds.

And verse 24 says:

Just as a person whose mind is deluded

Sees magical illusions and mirages,

And the cities of gandharva spirits,

So too forms and so on are perceived.

Here, deluded means our mind is deluded. Our mind is affected by mistaken appearances. For instance, when a magician recites certain mantras then there are many magical illusions that appear to the mind. Or for instance, when a certain kind of light hits sand then mirages appear. And then there are the Gandharva spirits. They say that in some places you see these Gandharva spirits, these spirit beings. Maybe it’s because of karma. We don’t know where this mistaken appearance comes from; maybe there’s a karmic connection. In some places, people apparently see this huge city. Although it’s like an isolated place, still people have a sense that there’s a whole city. Actually, when you come closer, there’s nothing there. That’s called the city of Gandharva spirits. Gandharvas are non-human spirit-like beings. And people have these appearances apparently, but that’s a mistaken appearance. In reality, it doesn’t exist. Similarly, there are so many objects around us. They appear as forms, they appear as sounds, and so forth, but none of these are based on partless atoms.

Then verse 25 says:

To overcome grasping at selfhood

[The Buddha] taught aggregates, elements and so on.

By abiding in the [state of] mind only,

The beings of great fortune even renounce that [teaching].

This verse is also refuting these partless atoms. We also refute, basically, external phenomena. This is what the Cittamatra school says. But the lower school would say, “No, the Buddha taught external existence. The Buddha taught aggregates, elements, and so on.” If we say, “By abiding in the state of mind only, the beings of great fortune even renounce that teaching,” that means like you’re renouncing the Buddha. You’re refuting the Buddha. But that’s not true. The answer that Cittamatra would give is that that is just to overcome self-grasping. That’s the reason the Buddha taught external existence, truly existent phenomena. Therefore, there’s a reason for saying “By abiding in the state of mind only.” It’s actually not necessary to say that it’s exclusive to the Cittamatra school, though, because also the higher schools would say that everything is dependent on the mind. So, we can also talk about the Madhyamaka school here that argues that everything is dependent on the mind; there are no truly existent external phenomena. They would argue in the same way.

Usually, when we think of the Mind Only school, we think of the Cittamatra, but here it can also include the Madhyamaka school. So, this is agreeing with the Cittamatra that there are no truly existent external phenomena, and that the mind is needed. The mind without the mind phenomena couldn’t exist. Whatever exists, it is an appearance to the mind. And the way it appears to our mind doesn’t exist in reality. By abiding in that state of mind only, the beings of great fortune even renounce that teaching. That view of truly existent external phenomena is renounced. The beings of great fortune renounce that view.

Next time we’ll continue with verse 26, which refutes the Cittamatra school.

Questions & Answers

Audience: If a human sees the Ganges as water and a preta sees the Ganges as an empty riverbed, then the human needs a raft to go over the Ganges while then the preta could just walk over it. So, they function differently. If they’re both liquid, how can they function differently?

Yangten Rinpoche: It’s actually possible that sometimes when we see water, a preta being sees nothing, just an empty plane or maybe pus and blood. Both are possible. Think about a celestial being of the formless realm. We see a house; we see a roof. But a being of the formless realm doesn’t see anything. They don’t see anything. There’s no contradiction here that they have no appearance of anything material or physical. They function. This is not a mistaken appearance, by the way. This celestial being of the formless realm perceives what’s actually there. In the case of being mistaken, if we don’t see anything even though there actually is something, then we’d be obstructed by certain objects. But here, this is a perception that is based on karma. A human being perceives physical objects; a formless being perceives nothing. So, from our vantage point, it’s contradictory.

Let’s take, for instance, just a liquid here. So actually, we perceive water. Then an animal perceives something very different, or a preta being perceives pus and blood. That is contradictory to water as well. It’s actually said that when you have this basis of some liquid there, three beings perceive something totally different simultaneously. Simultaneously, three different beings perceive something totally contradictory. But they all exist. At the time of these three beings, because of different karma, three different beings perceive it differently. In general, this is in relation to the different beings. We don’t say that in general, all these three factors are in there. It’s not saying that the water is all three. It’s nectar and pus and blood and so forth. We’re just saying that this basis here is this. So, there’s a similarity between what we perceive. There’s a similarity in that it’s all liquid, but we all perceive something different. We don’t say that this one object is all three. We don’t say that one object is water and nectar and so forth. It’s because of our karma that we perceive different things.

And they all exist at the same time, but they’re not the same thing. For instance, consider grass. If I were to give you some grass to eat, you wouldn’t consider that to be food. You’d probably get angry if I gave that to you to eat. But if I give it to a cow, they’d be very pleased. They would be very pleased. Therefore, on the basis of one object, there are different perceptions possible. This is just an example. I’m not saying it’s all the same. Previously, we talked about karma, so from the point of view of these three beings, they’re very different objects that are perceived. Nectar or pus and blood are all so different.

To give another example, when they accumulate a lot of negative karma then the preta beings stay in the winter. When it’s really cold, we human beings go outside and the sun shines. It’s a very pleasant experience. But for the preta beings, it’s quite different. When they’re exposed to the sun, it doesn’t warm them. The experience they have is not being warmed by the sun, but instead they feel colder when they’re exposed to the sun or when the sun shines on them. So, they have an opposite experience than we do. For us, we experience that the sun warms us, especially in the winter. When it snows a lot and then when you go outside and the sun shines, it warms you. It’s a pleasant experience. But the preta beings have a very unpleasant experience. It’s the opposite. And there are so many examples of different beings that are so totally contradictory.

I gave you the example of grass before, but it’s not just grass. For instance, it’s like when two people look at one object. So, maybe we’re looking at my friend. When I see my friend, I see a very pleasant person, a really good person. When they smile at me, I’m really happy. Even if they make a mistake, even if they do something that is unpleasant, I’ll just feel slightly uncomfortable. It doesn’t really affect my relationship because I usually see this person as really good. But then another person may see my friend as an enemy. So, whatever they do, it’s just negative. Even something positive doesn’t count at all. And then there’s another person who sees this friend of mine as a stranger. We have so many contradictory views when it comes to one person. The same is true for the vessel with liquid: the three beings perceive something totally different.

And this holds true also when they drink it: those who perceive pus and blood drink pus and blood. And so forth. This is what it says in Entering the Middle Way. And Asanga in one of his texts also talks about that. So, if we think about this, if we apply the different reasonings, we can analyze whether this is true or not, whether we do have contradictory perceptions. The Cittamatrans usually say that the imaginaries are not truly existent, but the dependent phenomena and the thoroughly established are truly existent.

Audience: When we perceive this suffering of the pretas, and they can’t even go outside, how do we cultivate compassion for these beings who are suffering in this way? As you describe the suffering of the pretas, a picture appears in my brain of a being who is suffering. My response is to cultivate compassion and not grief or cruelty—to not rejoice in their suffering and to not be overwhelmed by that suffering. So, I think, “It would be wonderful if the pretas were free from that,” and then I try to find the joy that will give me the resilience to accept the fact that there are lower realms. Is that the skillful way to approach the suffering that we have to accept?

Yangten Rinpoche: When we talked about the preta beings, for instance, it was in the context of understanding reality. It was in the context of understanding that because of the different imprints, we perceive things in a certain way that there are no external kind of partless atoms and so forth. We just talked about reality: how do phenomena really exist? In this case here, it was very much to do with basically understanding our own afflictions, our wrong views and so forth. But there are many different contexts in which we talk about the pretas. One reason is that if we talk about the suffering of the pretas, the hungry ghosts and so forth, we generate compassion on the basis of that. That’s one reason why we talk about it.

But we also meditate on the different types of existence or the different types of realms. Based on that, we also practice compassion or generosity. For instance, when we eat or drink something, we offer it to the pretas. As a bhikkhu or bhikshu, you take the last of the food and make like a seal. You take the last piece of food and you squeeze it together in your hand, like you seal, and give it to the preta beings. So, you can practice in terms of generating compassion, but also to help them, to benefit them. Where does the suffering come from? We also need to reflect on that. It comes from negative causes and conditions that have been accumulated. We can use that also in terms of our own practice to make sure that we don’t accumulate the same kind of karmic causes, and to help others not accumulate this kind of negative karma. It’s to inspire others, to help others, to advise others, so they don’t accumulate the same causes and conditions. There are so many different ways to think about it: in terms of our understanding reality, in terms of our own situation, in terms of compassion and so forth.

Part 1 in this series:

Part 3 in this series:

Yangten Rinpoche

Yangten Rinpoche was born in Kham, Tibet in 1978. He was recognized as a reincarnate lama at 10 and entered the Geshe program at Sera Mey Monastery at the unusually young age of 12, graduating with the highest honors, a Geshe Lharampa degree, at 29. In 2008, Rinpoche was called by His Holiness the Dalai Lama to work in his Private Office. He has assisted His Holiness on many projects, including heading the Monastic Ordination Section of the Office of H. H. The Dalai Lama and heading the project for compiling His Holiness’ writings and teachings. Read a full bio here. See more about Yangten Rinpoche, including videos of his recent teachings, on his Facebook page.