Establishing the sangha in the West

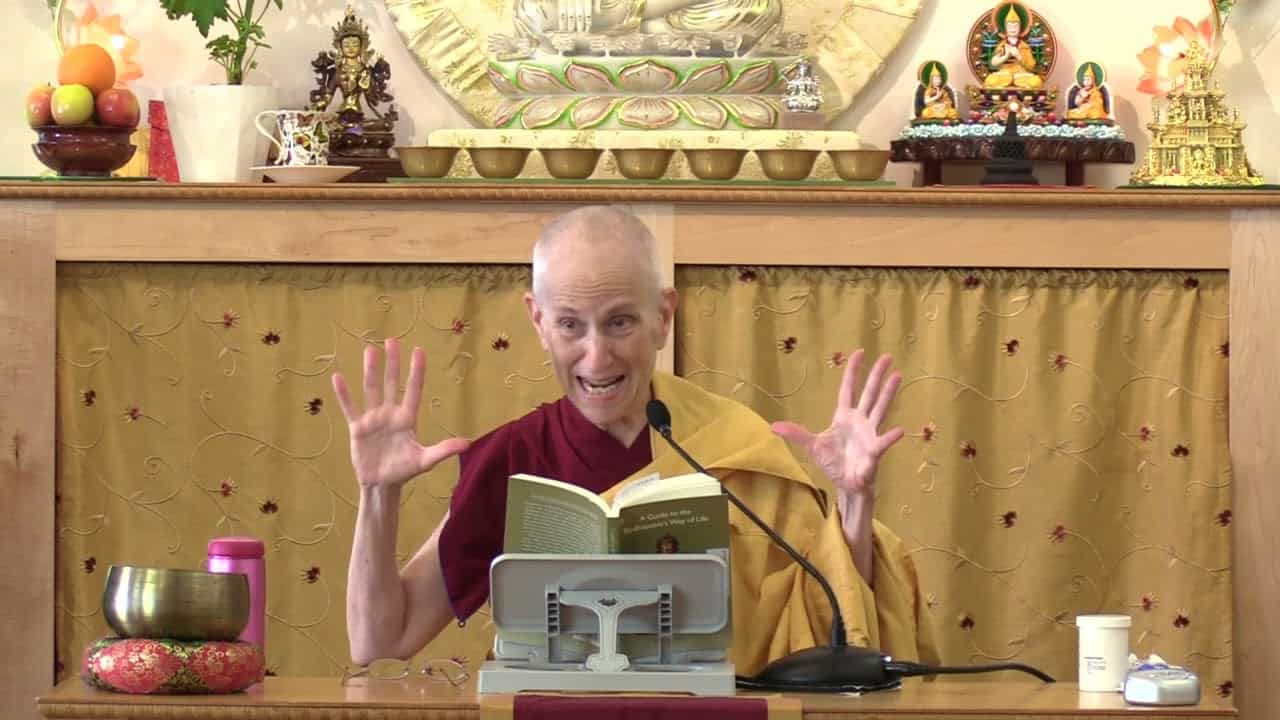

Venerable Thubten Chodron meeting with sangha at Root Institute in Bodhgaya, January 2023.

At the request of the director of Nalanda Monastery in France and nuns from Detong Ling Nunnery in Spain, Venerable Chodron spoke to a group of monastics about monastic training at the Abbey. The lively discussion transcribed below covered, among other topics:

- Venerable’s vision for building an interdependent community through the shared values of transparency and cooperation;

- Structures and processes for taking care of the physical, mental, emotional, and Dharma needs of the sangha;

- How holding the Vinaya is essential for community life in a monastery;

- Pre-screening, preparing, mentoring, and training community members.

The talk took place at the Root Institute in Bodhgaya, India in January, 2023.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Let’s take a minute to remember our motivation. As sangha members, our responsibility is not only for our own practice but also to sustain the Dharma. To learn the Dharma, sustain the Dharma, to be able to pass it on to future generations, and to share the Dharma with whoever comes, whoever is receptive and wants to learn the Buddha’s precious teachings. As sangha members, we are responsible especially for holding our precepts well and for holding the Vinaya tradition, and making ourselves qualified to pass it down and encourage other people who are interested to ordain and join the sangha. We’re doing all this for the ultimate long-term goal of attaining full awakening so we can benefit others most effectively.

Audience: Thank you so much.

VTC: How would you like to begin? What is important to you?

Audience: Nalanda has been going on for 40 years and we are having a different moment of the community. The community is maturing in some ways; monks have been living their entire lives in Nalanda and dying in Nalanda. We had one monk who actually died last year in Nalanda. We started to realize that this is going to be a place where people are actually going to get ordained and then probably die in Nalanda. So we wanted to share some ideas and of course hear from experiences of places that have been very successful as monastic communities in the West. So please you can talk a little bit about your idea, when you set up Sravasti Abbey and how it started. What do you see is actually happening and what do you feel are areas we need to improve? Something like that.

VTC: I lived at FPMT (Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition) centers for many years and at Kopan Monastery and at the Library in Dharamsala. It was very clear to me that Dharma centers are mainly for the lay people. They are geared toward lay people, and the sangha are the people who come and assist and very often hold menial positions. But I really wanted to live in a monastery that was a community, to live with other people who were like-minded. Lay Dharma students are wonderful, but their purpose in life is very different than our purpose in life, I think. When you’re a sangha member, you’ve dedicated your life to the Dharma. It doesn’t mean you are totally renounced, but in your mind that’s what’s most important to you, and it determines how you make your decisions. In lay life there’s just many distractions, with family, social life, financial concerns, and so on.

After living in Dorje Palmo Monastery and attending teachings at Nalanda Monastery for many years, I wanted to see a monastic community where the people are supported financially, where this is their home, where they don’t have to pay. That’s not the case in many monasteries, where monastics have to pay to live there. Personally, I feel that is outrageous. The Vinaya says when you ordain people you’re supposed to take care of them in terms of food and clothing, and in terms of Dharma: food, clothing, shelter, and Dharma. But the Tibetan tradition generally doesn’t do that. Maybe in some khangtsen1 it does and you get some support, or from group pujas you receive meals and offerings. But basically as a Westerner, you ordain and then…. [silence and laughter] Well, you know.

Audience: We know!

VTC: And there’s rich sangha and there’s poor sangha.

Audience: Yes.

VTC: I was one of the poor sangha. I am quite concerned: How can you ordain and then be expected to support yourself and keep your precepts at the same time? To be a real sangha member you can’t do that. You can’t hold a job. I’m sorry if I say things that push people’s buttons. I’m quite straightforward and am telling you my ideas. They may not agree with your ideas. That’s fine. I’m not criticizing you if our ideas aren’t the same. I’m just telling you what my experience and thoughts are.

So I wanted a place where I could really settle down. Not just for me, but I saw so many Western monastics, myself included, being like ping-pong balls. You’re sent to this center and that center and all over the place. You don’t have any control. You’re trying to learn the Dharma and you’re bouncing around the world working in Dharma centers.

I felt very strongly, from the beginning with Lama Yeshe, that the sangha as a community was so important for the establishment of the Dharma in a place, even though in the West there’s so many lay teachers. People often think that the sangha is a tradition that’s patriarchal, hierarchical, old-fashioned, and unnecessary. Some lay people say the sangha is suppressing our sexuality and escaping from the world. You know, you’ve heard it all.

I don’t think that’s what the sangha is doing. I think people have really good motivations and they come in with very good motivations. They need to be taken care of. Not only with the physical needs but with mental and emotional needs, Dharma needs. People are whole human beings and our communities have to take care of everybody in a whole way, not just by studying the classical texts. The texts and that kind of education is wonderful. I love the studies, but I’ve also realized you can study and learn a lot, without practicing or transforming your mind.

For many years I was active within FPMT and then at a certain point…. Well, it’s not necessary to go into the whole story but at a certain point I asked Lama Zopa Rinpoche if I could make my own decisions. He asked me to go to a certain Dharma center, but it didn’t work out. So I sent a message asking if I could make my own decisions. And he said “Yes.” So I came back to India for a while, and then I was resident teacher in Seattle, teaching at a Dharma center. It was an independent center, it wasn’t associated with any international organization. The people there were wonderful, but I wanted to live with monastics, and I felt that monasteries were so important. So I wound up starting Sravasti Abbey.

Sravasti Abbey is independent. It doesn’t belong to an international organization. That was a deliberate decision because what I had noticed is when you belong to an organization where the lamas are highly revered, then everybody only listens to the lamas The Tibetan system generally functions this way. It doesn’t function horizontally, with people making decisions as a group. Everyone looks to the lamas to tell them what to do, so people do not know how to cooperate and do things together as Westerners. For every decision, everybody asks, “What does Lama say? What does Lama want us to do?” People can’t work together so there is quarreling, competition, dissent, and jealousy over who gets to be closer to the lamas and who is outside, not close to the lama. Sorry if I’m talking about things that are obvious that nobody talks about. It’s true isn’t it?

Also, Western monastics don’t know how to open up. Everybody is sitting there. We’re trying to deal with our minds, which are just bananas. But we don’t want to talk about it because we’re all trying so hard to be good monastics, aren’t we? “I’m a good monastic, so I’m not going to talk about my problems, because I don’t have any…. Until I go to my room and I’m depressed and I’m upset. Nobody understands me and I don’t have any friends. What am I going to do?”

I saw that as a real problem, especially with the Western sangha. There’s a value that we hold very strongly at Sravasti Abbey—it’s the value of transparency. In other words, we let people know what’s going on with ourselves. We’re not trying to create an image of being some high, elevated practitioner who doesn’t have any problems, who understands everything…. No. We’re human beings and we want community, we want to belong and to contribute to a group that is working for something bigger than ourselves. But as Westerners, we don’t know how to make community. Tibetans join the monastery when you’re a little kid, your uncle or aunt is a monastic in that monastery and they take care of you. You’re in a khangtsen with people from your own area of Tibet; you speak the same dialect.

We Westerners come along and we’re from diverse countries, speak diverse languages, and we’re ping-pong balls going all around the world. We want community but we don’t know how to do it. We don’t stay in one place long enough to develop a monastic community. Plus we’re all trying so hard to be good and we have a hard time talking about our problems. Or if we talk about them we just: [wails]. It’s like this drama! So Sravasti Abbey is set up with a common goal for the community and for us as a group of individuals. We’re not here for my Dharma practice, my education, where I can study, what I can learn, where I’m going to do retreat, how often I get to see the guru, how much I’m admired for how much I know. That’s not our purpose.

Our purpose is to establish the sangha in the West and in that way, to spread the Dharma in the West. We want to make something that will continue for many, many generations, a long, long time after we’re gone. We want the Dharma to remain in the world so other people can meet and learn it, just like previous generations of monastics in Asia held the teachings and the ordinations and passed them down so that we could meet and practice them. That’s a common value at the Abbey and you learn it when you come. To do that we have to function as a community. We’re not just an educational institute and we’re not a boarding house for monastics. Because an educational institute, a boarding house—you’re there when the programs and the teachings are going on, but when they’re not, then everybody goes where they want to go. There’s no feeling of taking care of the community or checking with the community about what you’re doing or where and for how long you’re going. It’s just whatever you want to do when classes aren’t happening—you go and do it. That’s not a community, that’s an institute. Can you see the difference between that and an actual monastic community where everyone works together?

When there is a monastic community, you join a community; this place is your home. You can go to other places and study at other places, but you check with the community first. Everybody agrees that it’s fine if you go away for a while because we all have the same aim. When you go to attend other teachings, do retreat, or visit family, you know the rest of the community supports you. You know that you will share what you learn with them when you return. Especially as a new community, we really need everybody on board regarding this point. People ask me, “Why didn’t Venerable Sangye Khadro come to the teachings in India?” Well, because we’re a community and three of us are already here. We’re 24 people so more people can’t go away at this time. But they’ll go to other teachings later and we’ll happily remain at the Abbey to keep things going.

So we work together as a community. We check: How long are you going to be gone, and where are you going? What are you doing? What about your responsibilities? Who’s taking over for your different jobs when you’re gone? We check with others. I’m sure everybody in our community would love to have come to the teachings, to go to Singapore and Taiwan with us on this trip, but everyone knows that only a few people go at a time. The Abbey does a three-month retreat in the winter every year, and that’s what the rest of the community is doing now.

Let’s go back to transparency, where people can really open up and say what they’re feeling, what’s going on with them. You can admit things to other people without feeling ashamed or guilty. We have what’s called “stand-up meetings” every morning—“stand-up” meaning that they’re short. You don’t sit down so it had better be short! We stand in a circle and everybody says something that they rejoice about in the previous day, and then they say what they’re going to do that day in terms of offering service work. Then somebody might say, “I’m in a really bad mood today. I’ve been in a bad mood the last three days, so please know that if my speech is a little sharp, that’s why. Please bear with me and be patient.”

People will talk about those kind of things. Everybody hears, everybody knows. It’s better when you’re upset or angry that you tell the community yourself, because anyway, everybody knows you’re in a bad mood. When we try and cover up our mistakes, when we try to pretend that we’re not angry, that everything’s fine, everybody knows that’s phony baloney. It’s so much better to share, because when you share like that, then everybody has empathy because everybody understands. We’re all in a bad mood at one time or another, so people understand. You’ve said it yourself, so they know you’re owning your behavior; you’re not blaming anyone else for it. Then people want to support you, they care about how you feel and want to help. I think that transparency is quite important. The Vinaya also speaks about transparency although it doesn’t use that term.

I think the way we hold Vinaya is really important for community life in a monastery. Do you feel that way? So we do sojong (posadha, the fortnightly confession and purification of monastic precepts). All of us hold the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, which is practiced in China, Taiwan, Korea, and Southeast Asia. Tibetans hold the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya. The reason we follow the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya is that the lineage for bhikshuni ordination exists in the Asian monasteries that hold the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya but not in Tibetan monasteries that follow the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya. So we decided—actually, I decided because I was the first resident at the Abbey—me and two cats, and the cats weren’t ordained, so they didn’t have a say in this! Our nuns want to become bhikshunis and now 11 of them have received that ordination. Now we also have some monks and they’re fine receiving their ordination in Dharmaguptaka. This way, by everyone following the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya, eventually when we have enough people who have been ordained long enough, we can give the bhikshuni and bhikshu ordinations ourselves—in English! So you can understand what the preceptor and acharya say and what you say. Right now we have enough nuns with seniority to do that, but we don’t have sufficient bhikshus at the Abbey yet…. Oh, there’s so many things to tell you! How do I get it all done in this short time?

I think one of the problems that happens with the Western sangha is that people are not screened and prepared properly before ordination, and they’re not trained afterwards. Anybody can ask a lama, “Will you ordain me?” And [the lama often responds], “Come tomorrow morning (in a week, etc.) with a bowl and robes.” You’re in and you’re out of the ordination after an hour and a half later. Then you stop and think, “Now what do I do?” Nobody has screened you, you’re not sure where to live or where your food will come from. You’re asked various questions during the ordination ceremony and nobody’s checked with you that you have those qualifications needed to ordain. No one has checked, what’s the situation with your family? Do you have children? I heard that some years ago somebody came to Tushita Dharamsala for the pre-ordination program. During the program he said he was ordaining and then going back to live with his wife and family. He didn’t know he was supposed to be celibate. To me it is so sad that people are not properly screened and adequately prepared for monastic ordination. This is not how the Vinaya set it up. You need to be screened, you need to be prepared, you need to know what you’re getting into so you can decide if this is what you really want to do.

At Sravasti Abbey, we have a system for getting to know people, screening them, and preparing them. People usually come as a visitor and participate in retreats and teachings for a while. Then they apply to stay as a long-term lay guest with five precepts. They do this for a while, then they request anagarika ordination, which is eight precepts. They hold the eight precepts for about a year and participate in life at the monastery. When somebody feels ready, then they request sramanera or sramaneri ordination (getsul/getsulma), since we have enough senior bhikshunis to give the sramaneri ordination and the siksamana ordination (the two-year training ordination for the nuns). Since we currently do not have enough Dharmaguptaka bhikshus living at the Abbey, we request a respected Chinese bhikshu, who is a friend of mine, to come to give the sramanera ordination to men.

Although according to Vinaya men can take sramanera and bhikshu ordinations on the same day, we don’t do that. We don’t do that because everyone, be they male or female, needs to get used to being a monastic before they go on to receive the full ordination. Also, gender equality is an important value for us, so everyone holds the novice ordination for at least two years before going to Taiwan for full ordination.

In the Chinese procedure for giving bhikshu and bhikshuni ordination, candidates have already lived in their home monastery for a year or two. They know what monastic life is like and most have taken the sramanera/i ordination with the teacher at their monastery. Their teacher refers them to the triple platform ordination program—a large gathering that is anywhere from one month to three months long and is attended by several hundred candidates. During this time people are trained in monastic etiquette and the sramanera/i and bhikshu/ni precepts. The ordination ceremony is explained to them and they rehearse the ceremony. That way everyone understands what is going on.

It is called triple platform because during the program the sramanera/i, (also siksamana for nuns), bhikshu/ni, and bodhisattva ordinations are given. Because there are so many candidates, in addition to the teachers, Vinaya masters, and a lot of lay volunteers who support the ordination program, you live squished together, have little privacy, and your days are full with teachings, training, and purification practices. Your days are full of Dharma from morning till night. We Westerners live in a different culture with different customs and sometimes have a hard time adapting to life in another culture. A simple example: I had just gotten used to sitting for hours and hours during pujas in the Tibetan tradition, and then I went to Taiwan for full ordination, where you stand for hours and hours—which made my feet swell. But I didn’t complain because it was so valuable to experience a program where they teach you from the beginning how to wear your robes, how to fold your robes, how to walk, how to sit, how to eat, how to speak to people so you’ll bring harmony, and so forth.

Historically Chinese culture has been very refined, whereas Tibetans lived in a rougher climate and many were nomads. We Westerners are sometimes oblivious to how to conduct ourselves in various cultures. Lama Yeshe used to tell us, “As a monastic, you have to present a good visualization to people.” You can’t just be all over the place, bouncing off the walls, talking loudly, laughing hysterically, going to movies, staying up late surfing the Internet. In the Chinese program, people receive training, which increases our mindfulness. We must be mindful of how we move through space, where we sit, how to greet various people, the volume of our voice, our mannerisms, showing respect to seniors, and so forth.

For many years, the Abbey has held a two to three-week long Exploring Monastic Life program every summer for laypeople who are interested in ordination. In 2021, we started having a siksamana training program in the autumn that our anagarikas and sramanera/is also attend. We don’t usually publicize the siksamana training course, but if people who live elsewhere want to come, they can apply.

At the Abbey, we make sure that people are screened and prepared well before they ordain—they’ve settled any issues with their family, they have enough money for their medical and dental expenses (the Abbey covers monastic’s medical and dental expenses only after they are fully ordained. No one pays to stay at the Abbey or to attend teachings and retreats). They know where they will live, they know who their teacher(s) are, they have a daily practice, and have lived at the Abbey as an anagarika for at least a year before becoming a sramanera/i.

During our regular schedule, we have Vinaya class every week. People often think that the most important thing to learn as a monastic is the precepts. But being a monastic isn’t just about keeping precepts. There’s so much more to learn and to train in. Nevertheless, it’s important to know the precepts you have received. It happens that people have read the precepts but haven’t received teachings on them right away. How can they be expected to be good monastics if they haven’t been taught the basic elements of monastic life?

There’s daily training going on as well as the Vinaya course. We talk a lot about what a monastic mind is and what it means to be ordained. What are your privileges, what are your responsibilities? What is a monastic mind? What is your attitude? Being a Buddhist monastic involves a total change in how you look at life. You have the Buddhist worldview; you understand and respect the law of karma and its effect; you want to create virtuous karma. You want to benefit sentient beings. You still have problems and obscurations—all of us do; we’re all in samsara together and our job is to get out and to help one another and all others to be free from samsara.

In our Vinaya class and in the siksamana training program, we discuss how should monastics relate to lay people? To your family? If your teachers are from a different culture or if you have lay teachers, how do you relate to them? What is appropriate behavior and speech in different situations we may encounter, for example if you visit old friends and they invite you to go to the pub? The class and program are so rich because people really share ideas and learn from each other.

You receive training daily just by living in a monastery. We live together and things come up. People don’t get along and people have hurt feelings….you know what it’s like. Things happen, but we talk about them. From the very get-go we let people know that our daily life is the environment for our Dharma practice. Our life isn’t solely about attending teachings, studying, and attending pujas and meditation sessions. It’s about living a Dharma life. That means when people aren’t getting along, they learn to own their interpretation of events, their projections on others, and their own emotions. They try to work things out—in their meditation practice or by talking with the other person—and if they run into problems, they ask a senior for help. If I’m around and see someone acting inappropriately, I call it out right away. I’ll either address the whole group, or give a talk about it during our BBC talks. BBC stands for Bodhisattva’s Breakfast Corner—these are short, 15-minute talks that we have almost every day before lunch. Years ago, it started out with me giving all the talks, but now everybody takes turns and gives talks. In the BBC talks, people will share what they’re working on in their practice, they explain how they solved a problem using the Dharma, or what they read in a book or heard in a teaching that made a strong impression on them.

Audience: When you say that when you have some issues that people talk about it, please share how you do that; how do you talk about it? Do you have small groups? Does someone mediate? How do you deal with issues?

VTC: To explain that I have to back up a little bit. Our courses for the public consist of teaching sessions, meditation, and discussion. We have a way of doing discussions where the facilitator chooses a topic and composes three or four questions about it. While everyone is meditating, she’ll ask the questions one at a time and then leave some silent time so people can think what their responses are to the questions. The questions all have to do with what does some Dharma teaching mean to you or how do you integrate that in your life? It might be what does refuge mean to you, with three or four questions about that. Many times the discussion groups are personal questions: Do you get lonely? What does loneliness mean? How do you feel when you’re lonely? What do you need when you’re lonely? What ideas do you have for working with your loneliness? Questions like that.

Everybody thinks about them. Then, in groups of 5 or 6 people, we go around and one by one, everybody shares their reflections on those questions. At that time, there’s no crosstalk, everybody just shares. At the end, there’s time for crosstalk and for people to share with each other, and there is a debrief of the whole group together at the end. Whoever was leading debriefs the group.

So right away from the beginning, when people come to the Abbey, they get used to talking about themselves and what Dharma means to them. When something comes up in the community, people are used to talking about it. It sounds great in theory, but we all know that when people are riled up… So we encourage people to work out their role in the problem in their meditation before talking with the other person or people involved.

Nobody is satisfied with everything at the Abbey. When people come to live at the Abbey, I tell them there’s three things nobody here likes. You will not like these three so just know that nobody else here likes them either. The first is the schedule. Everybody wants the schedule to be different. It’s not going to be different, this is what it is. Live with it. Okay? We’re not changing the schedule every time a new person comes. [laughter]

This is what happened when I lived in a new monastery years ago. A new person comes and they complain until we have a long meeting and change the schedule. We make the meditation sessions 5 minutes shorter and begin morning meditation 5 minutes later as the new person wants. But they keep complaining. Soon they leave and go somewhere else. Then another new person comes and wants to adjust the daily schedule so that it suits their personal preferences. That’s not how we do things at the Abbey. So nobody likes the schedule. There’s nothing to do about it except accept the schedule and adapt.

Nobody likes how the chanting and the liturgy is done either. [laughter] The chanting is too slow, the chanting is too fast. So-and-so can’t hold a tune for the world. Our chanting is an offering to the Buddha but it sounds like a bunch of turkeys!” [turkey noises and laughter]

The third thing nobody likes is how the kitchen operates. We take turns cooking, we’re international, so everybody cooks. One day you have vegetarian meat and potatoes “a la Maine,” you know, Maine in America, Quebec, that kind of diet. Then you have some days with a Singaporean diet. Actually we have three Singaporeans. Then you have German food. You have—

Audience: Potato salad.

VTC: and heavy bread. Then Vietnamese soup, which is delicious, but the next day there are patties made from leftovers. Whoever cooks that day is the one in charge. If you’re an assistant, you chop vegetables and clean up. Sounds simple, but the cook wants the carrots cut this way, and you think it’s better to cut them another way. Then a debate starts over how to cut the carrots. You know the right way to cut the carrots, but the person who’s in charge of cooking that day doesn’t want them cut in that way. They don’t listen to you, and they tell you how to do it and nobody likes to be told what to do, do they? The person who loses the debate feels like no one hears them, no one respects them.

Audience: Sounds like us.

VTC: No, really?! Somebody tells you you’re on dishes. “I’m on dishes again, I was on dishes yesterday! It’s not fair!! I have to do dishes more often that so-and-so.” When they happen, sometimes I’ll talk to the community about it. Sometimes I’ll dramatize it. “Oh, whoa is me, I have to wash three more dishes than someone else. This isn’t equality! This is oppression. I’m going to make a placard and protest in front of the monastery!” It helps to create an absurd scene so people can laugh at themselves. Then I’ll talk about what it means to be a community and to be a team player. To be a community, everybody must care for the monastery and the people in it and be a team player. We emphasize this a lot, over and over again, because it takes a lot of repetition for us to understand what being a team player means. If you say it once it goes in one ear and out the other. People need to hear it again, and again, and again.

“We’re glad you vacuumed the floor, the carpet last week, that’s very good. Thank you very much for your generosity of spending 20 minutes of your precious human life vacuuming….And you’re on the rota again this week to vacuum.” [laughing] If this is the biggest problem in your life, that’s good! The real problem is not who’s vacuuming the floor; the real problem is, “I don’t like to be told what to do.” We’ll have a lot of discussion about not liking being told what to do. In a discussion group described above, the questions will be: what things and in what kind of situations don’t you like being told what to do? How do you react when someone tells you what to do? What are you thinking that you react emotionally like that? These kinds of questions help to get people to think about how they relate to being told what to do.

One thing we do in community that I think is important is we learn to laugh at ourselves. This is so important. If we’re talking about not liking to be told what to do, it’s a teaching moment so I’ll say, “Oh yes, before asking me to do something, it would be so nice if people came, made three prostrations, offered me something, kneeled with palms together, and respectfully said, ‘Please would you mind doing the dishes? If you did the dishes everyone would honor you as a bodhisattva for the next five eons and you would create merit as large as the universe.’ It would be so nice if everybody was respectful and asked me like that. But these people they are so disrespectful, they just say ‘Do it.’” Of course by that time everybody has gotten the point and is laughing.

I find humor very important for conveying important messages, to really make the situation quite absurd so we can see how our minds are attached to stupidaggios. That’s one way to deal with conflict. But you have to be someone respected in the community to do that; otherwise people don’t like it.

Of course, it isn’t skillful to use humor too much. We have to be sensitive and know when it’s more effective to be serious. At those times, we usually turn to Marshall Rosenberg’s NVC or Non-violent Communication. It’s beneficial to study NVC together as a group; then when conflicts arise, everyone knows how to use it…that is, if they remember it then. When people get all worked up, they forget and go back to their default modes of dealing with conflict, which usually don’t work so well.

We do posada—sojong—twice a month. Bhikshunis confess to one another, so do the monks. Then the sramaneris and siksamanas confess to the bhikshunis. It’s not a general confession but you actually say what you did and which precepts you broke. In this way we learn to be transparent. You have to say it and people hear it. This teaches us to relax and accept ourselves and our faults without trying to hide them or justify them. We can be transparent with one another because we know everyone is being transparent.

Audience: Can I ask you please about a problem between two people, like a specific situation like, you know, “Ah he did that to me”— this is a lot of my job at Nalanda and I’m quite young. Some people have a problem and then they say, “Oh this person did that to me….” “He closed the door in my face,” or whatever.

VTC: Yes, “He woke me up in the middle of the night when I was sleeping. Why can’t he hold his pee until the morning?”

Audience: Exactly. [laughter] Those kind of issues, it can affect everyone, these dynamics….

VTC: Oh yes. As a community we studied Nonviolent Communication by Marshall Rosenberg many years ago. Whenever there is a group of new anagarikas, we introduce them to NVC. NVC is very helpful because Marshall talks about feelings and needs. Much of what he says is in accord with the Dharma. Some of it is not because NVC doesn’t include the perspective of rebirth, samsara rooted in self-grasping ignorance, and karma and its effects. But it gives people the idea of having to listen to others from our heart and to rephrase what they say, instead of formulating your angry response while someone else is talking. Instead, you learn to reflect what the person says so that they know we have understood and heard them. You say it in a calm voice so they know that you care; you’re not radiating angry energy.

Also, when conflicts occur we encourage people to use thought training and the teachings in Shantideva’s Engaging in a Bodhisattva’s Deeds. When someone is angry, we listen to them without taking sides. Then we remind them, “When you have a problem with somebody and something may have happened between the two of you, this is the time to notice your afflictions. When there’s a problem, there’s afflictions in the mind, so your frustration or irritation is giving you information about what you need to work on. When you have a problem, don’t come and say, ‘He or she did this and they did this and they did that.’ Come and say, ‘I’m upset and I need help with my anger.’” In other words, the problem isn’t what the other person did, it’s our afflictions.

Everybody has a mentor, so you may talk one-on-one with your mentor about the situation, your response to it, and your contribution to it. Sometimes you ask a senior to help you sort out what you feel, what is the appropriate antidote for the affliction that is currently disturbing your mind. Sometimes the senior will help two people talk to each other. The basic thing is always what’s happening in my mind? If I’m upset, that’s what I have to deal with. This is not about devising a strategy to get the other person to do what I want.

Audience: Everyone has a mentor?

VTC: Yes.

Audience: How does that work?

VTC: We have juniors and seniors. Not all the seniors are prepared to be mentors but those who are have a mentee. Mentor and mentee.

Audience: Like a buddy system?

VTC: Yes, like a buddy. We used to call it a buddy system but we changed it to mentor. The mentor and mentee usually meet once a week—some meet once every two weeks. You discuss how you’re doing and what you need help with with your mentor. If something’s really brewing under the surface and it’s not getting resolved, sometimes people will refer it and I’ll talk to the person. Sometimes one mentor will meet with two people who are having problems. It depends on the situation.

Audience: Would you agree that having that level of good communication would be a key element for a harmonious community?

VTC: Oh yes!

Audience: It’s all about communication.

VTC: Yes, we have to first learn to identify what we’re feeling. Many people were not brought up in a family where they learned the words to express their feelings. Some people have to start with that. “What do you feel?” “I don’t know.” “Make a guess. Is it a pleasant or unpleasant feeling? Do you want something or are you pushing something away? People have come from different backgrounds, so some can easily identify their feelings and needs, while others have a more difficult time doing that. Some cultures are emotionally expressive, others are not. Even within one culture, people diverge in this way.

You learn so much about people by living in a monastery. For some people, their real need is just to feel safe. Especially if they’ve experienced abuse in the past. They view the world through the lens of safety: “Where am I going to be safe? Who can I trust? Is this person kind or will they criticize me?” With them, you have to talk about safety and help them to explain what kind of safety they need and in what ways can other people show them that they are friendly. What are the signs of feeling safe? When we hear “safety,” some people think of physical safety, some people think of emotional safety. What does safety mean to you? What would it look like? What do you expect from other people? You have to get to what the underlying issue is.

Audience: To do that, do you bring in a therapist?

VTC: One of our nuns was a therapist for many years before she ordained. She won’t do therapy with them because that mixes roles, but she’ll talk to them and get them to express themselves more.

Audience: Which is really helpful.

VTC: Yes, it’s really helpful. But I think even those of us who aren’t therapists, as we train over time…

Audience: Yes, you become one. Like a Dharma therapist.

VTC: Yes, like a Dharma therapist. Or Lama used to say “Everybody needs a mother, so you’ve got to be mamma.” No? Even to the men. [laughing] Yes?

Audience: Yes.

VTC: Yes, because everybody needs to feel accepted, to feel understood, to feel valued, to know that they belong and are respected. If you look in a deeper way, you can say these are all attachments that we have to overcome on the path because they’re all somehow ego-related. But at least at the beginning and for a long time, it’s helpful to accept that these are basic human things in a worldly sense. But until people feel comfortable, until they know that they have their best interest in mind, it’s hard for them to feel comfortable expressing them. Instead they may just stuff their emotions and can’t get beyond them. That creates a barrier to understanding the Dharma.

Audience: I agree.

VTC: But we don’t only suggest therapy when someone needs more help than a mentor and the community can give, because therapy is not the Dharma. We bring in a lot of lojong, thought training.

Audience: I guess sometimes when some people are so traumatized it’s even hard to start with that.

VTC: Yes, so that’s where two things come into place. One is the need to screen people well before they ordain. If someone has experienced very severe trauma or is mentally ill, they may want to ordain but not be ready to. A monastery is not designed to help people who need mental health services from professionals. The second is that the senior sangha members in the monastery decide who can ordain. When we started at Dorje Palmo Monastery in the 1980s, the lamas determined who ordained and we had to accept everybody into the monastery, and that doesn’t work.

Audience: That’s how it works at FPMT nunneries and monasteries.

Audience: Well, not really. This is one of the things that has been changing a lot, especially in Nalanda Monastery and Detong Ling Nunnery. It was decided that it will depend on the community. The person needs to apply, and in Nalanda Monastery now we have a screening process and things like that. So actually there is a training, and then the gelongs need to approve.

VTC: That’s so much better. Also, in Vinaya although only 2 bhikshus or bhikshunis are needed to give sramanera/i ordination, a complete sangha is necessary to give full ordination. The sangha has to agree to ordain the person, it is not the preceptor’s decision alone to make.

Audience: Yes, and if they have already ordained, even if they say, “Rinpoche told me it’s good for me to come to Nalanda.” They still need to pass through our inner process.

VTC: That’s good.

Audience: We can accept them to come, if they follow, but then they still need to pass the screening.

VTC: Yes. You can’t create a monastery that meets everybody’s needs and desires. Let’s face it, some people who have severe mental problems may want to ordain. The Tibetan lamas cannot necessarily tell who has mental problems and who doesn’t. They don’t know English or other European or Asian languages. They don’t know the culture. I’m glad to hear Nalanda is changing, but usually it isn’t that way. In most places, the lama decides if a Westerner can ordain. But if a person is going to get ordained and live in a community, it has to be the community who decides. If the person ordains somewhere else—some people who ordained somewhere else later want to join the Abbey. We screen them and if the community approves, they have a probationary period of a year so they can get to know the community better and we can get to know them.

Audience: We have the same.

VTC: First of all, the bhikshunis meet together and we decide if we think somebody is suitable and is ready to ordain. If somebody ordained elsewhere wants to join the Abbey, the bhikshunis usually discuss it first, and then the whole community does. If somebody says, “Oh, I don’t want that person, I don’t like them.” Well, not liking somebody isn’t a good reason. Or, “We have so much work to do. We need somebody with such and such a talent to do the work. This person is very slow to complete tasks.” No, that too is not proper criteria for deciding if someone can ordain or join the community. You have to assess their spiritual yearning and what’s going on inside them. Do they understand the Dharma? Do they really have a genuine aspiration? Or do they have an unrealistic idea of monastic life? Do they see becoming a monastic like a career choice? They think, “I want to be a translator. I want to be a Dharma teacher,” as if it’s a career and a way to be somebody. We should think, “I am a student of the Buddha until full awakening, and my ‘job description’ is to learn and practice the Dharma and serve sentient beings.” So we don’t hurry things up. People often want to get ordained quickly, but we’ve learned to slow it down and have them live with the community and try it out for a while.

Why slow things down? There have been people living in the community for two or three years, and you think you know them really well. They ordain and then a month, a year, three years later, they go into crisis and all sorts of things that weren’t a big issue for them before now becomes huge. They don’t want to cooperate, they are fearful, they are super sensitive, they have health problems or emotional problems that you didn’t know about. When you live in community, you’re constantly learning about people. You’re also seeing them improve and learn to handle their upsets, care more for others, and use their talents.

So that’s one thing. The second thing is, sometimes people have been ordained for many years and then something comes up and they feel like they need therapy, so we’ll refer them to a therapist. We’re not a therapeutic community. We’re a monastery. When you need therapy, we’re fine with that. If people are on meds, we encourage them to stay on their meds unless they talk with their doctor and slowly reduce the dose.

Audience: You said you try to have a holistic approach. I want to hear a little bit more about that, because at least in Nalanda Monastery we are based on study. I loved when you said about a monastery, “It’s not an institute, it’s not a home, it’s not a place where people just come and go as they wish, like a boarding house.” I think Nalanda Monastery has a bit of this problem right now, with the study program being the central aspect of the community. I’m so happy to hear about all these small things that you’re saying about how to actually create community.

VTC: Yes. We’re multifaceted human beings and so many different aspects of us need to be nourished for us to become a balanced person who can be of benefit to others and to society.

Audience: Because that is the point. I heard, before I came to Nalanda Monastery, the term “Hotel Nalanda,” and I was shocked. Now I understand why. Because actually when there’s no teaching, the monastery aspect falls apart in some ways. So I thought, “Ah! Okay! What does that mean? How can we actually change that?” I’d like to hear more, on a practical level, how do you divide the day-to-day activities? How much of an emphasis or time do you spend on study? How much time do you have for self-study? How is the day organized at the Abbey?

VTC: We can send you our daily schedule. That will give you some idea to start with.

Audience: That would be great! [laughing]

VTC: Our annual schedule includes three months of retreat in the winter. The rest of the year is really busy. We have a lot of guests; there are courses and retreats of different lengths for guests, so by the time winter comes, everyone is happy to keep silence. In the three-month retreat we have two groups: one group that is in strict retreat and the other group that does half-retreat; they take care of the everyday tasks—the office, etc. This is for half the retreat time—a month and a half. Then the groups switch, so that everyone has a month and a half in strict retreat and a month and a half in partial retreat with service. We’ve experimented with different ways; that way seems to work quite well.

I don’t know if the feeling of Nalanda Monastery is what it was when I was there in the early ‘80s, but maybe…. Okay. I’m going to be frank.

Audience: Please.

VTC: From what I’ve observed—and this refers to a community of men—when a group of men are together, they compete with one another. They try to prove to each other, to figure out who is the—what do you call it? The alpha male. Who’s the alpha male that’s going to be the boss. This kind of competition—which sometimes can be quite macho depending on the culture—that is not conducive for people to feel relaxed and at home.

In addition, as I mentioned before, we have this image of “the perfect monk,” “the perfect nun.” I’m trying to be that, so I don’t have any emotions. And especially for men: “I don’t have any emotions. Nothing’s bothering me. Nothing. I’m just quiet today,” as you fume. [laughter]

People have to learn to talk about how they feel. They have to learn to trust. That’s what the basis is; you trust each other as monastics; we are all in this together. We are all in samsara, we’re all trying to get out. This is not a competition. We are all helping each other. To do that we have to be open and transparent, and to do that we have to trust others and be trustworthy ourselves.

Audience: Why do you think it’s so difficult for monastics to open up? Why? [laughter]

VTC: Why? I think one factor is we come into the monastery with a fairy-tale image of what it means to be a monastic. “I am ordained now. I am a holy being.” You can always tell the new monastics because they will sit in front in a public teaching. Seniors are sitting in back. The juniors think, “I’m a monk, I’m a nun, I’ll go sit in front.” Our self-preoccupation is strong and we often can’t see it.

Sometimes the monks push against the nuns. “You’re only a sramaneri, I’m a monk. We sit in front of the nuns.” These kinds of attitudes make people quite miserable and they create a lot of discord. Even if you live in an all-male or all-female community, we have to have gender equality. I think that’s absolutely necessary. The way we do seniority at the Abbey is it doesn’t matter what gender you are; we sit in the order we were ordained as bhikshunis and bhikshus, followed by siksamana, and then sramanera/is.

So the monks and nuns are mixed together and we use the term “monastic,” to apply to everybody. But even then, some people get so attached to my place. And one person says, “Oh, I was a novice for 20 years before I could finally become a bhikshuni. But now, these bhikshunis who are newer to the Dharma are sitting in front of me because they received full ordination before me.” So I spend some time talking with that person. Some people are very sensitive about being respected.” Respect—that’s another one.

Audience: Yes, respect.

VTC: Everybody wants to be respected. When people don’t feel respected and they feel cast away, especially if that is done based on gender, ethnicity, seniority, or whatever, it doesn’t create a good feeling. So I tell people, seniority is just so that you know where to sit. It has nothing to do with how much you know, how well you’ve practiced, how much merit you have. It just is a way of organizing people. But some people are quite attached to where they are in the line. That’s just something we work with in the monastery and talk about.

Audience: Can we just go back because for me, one of the things I’m wondering is how to compose a yearly schedule that has all the aspects that we want monastics to be engaged in. You said, “We do three months of retreat a year.” So when was this decision made, why three months, why not just two months? How do you create this? One of the things that I feel we sometimes lack is a balance of the different components of monasticism, right?

VTC: Yes.

Audience: And of course the Dharma and Vinaya. You said you are giving Vinaya classes every week—wow. This is incredible.

VTC: Yes, sometimes the Vinaya class is short—just for an hour. But that’s also a time when I address the whole community about Vinaya. Vinaya is very practical and it concerns many aspects of our lives. It makes us more aware of our actions and our motivations.

To go back to our daily schedule: we have morning and evening meditations—an hour and a half each time. We do not miss morning and evening meditation. In some monasteries and Dharma centers people get really busy building, planning events, giving tours, doing admin, so people start missing morning and evening meditation, or sometimes meditation is canceled for everybody. That’s not a good thing to do in a Dharma community, and we don’t do that at the Abbey. As soon as busyness becomes more important than Dharma, that’s not a good sign.

Audience: And it’s compulsory for the whole community to join this morning and evening meditation?

VTC: Yes.

Sravasti Abbey nun: Someone will come and get you if you’re not there at the beginning of a meditation session.

VTC: Yes! But when I was the gegu (disciplinarian) of the Italian monks [laughter]… A nun being the gegu of Italian monks—can you imagine?

Audience: Oh, it must have been quite something.

VTC: Yes. I created a lot of negative karma! But they made me do it, it was all their fault! Not my fault—I was innocent! They just drove me crazy. [laughter]

Yes, everybody comes to morning and evening meditation. But if somebody doesn’t come, what we don’t do is go to someone’s room and go, “Bang bang bang. It’s meditation time! Get up! You’re late!” It’s not like that. It’s, “Tap, tap, tap. Are you okay? Are you sick this morning? Do you need something?” And then somebody will say “Oh, I overslept!” And they’ll get dressed and come in.

We do it like this because we care about each other. If somebody doesn’t come to meditation, we’re concerned. Are they sick? So somebody goes to check, and you do it gently and respectfully. It’s not like you’re bad if you overslept. Uh oh, I’m having a flashback to waking up Italian monks. Ohhh no! [laughter and sounds of VTC in pain.]

Audience: That’s why I said before, “I’m Italian!” to remind you.

VTC: Yes! [laughing]

Audience: But I was not a monk at that time. [laughter]

VTC: You’ve chilled out a little bit. You were as Italian as the rest of them. You’re chilling, you’re chilling. That’s good. [laughter]

Audience: And after the meditation?

VTC: There’s a half an hour break after morning meditation. Some people will continue their practice, but whoever’s on breakfast will prepare breakfast. Very simple breakfast. Then we have a stand-up meeting, which is really good. It gets everybody together in the morning and everyone shares something that happened the previous day that they rejoice about and then talks about what they will do that day. Any news for the community is said then. If someone needs help with a project or is in a bad mood and wants to be quiet that day, they say that. That is followed by offering service until lunch. Offering service is what other people call work. When you think of what you’re doing as offering service to the sangha and to sentient beings, your attitude changes.

We gather together at lunch and somebody gives a BBC (Bodhisattva’s Breakfast Corner) talk for 15-20 minutes. We offer our lunch together, reciting verses and then eating in silence for half the meal. Breakfast is taken in silence. Halfway through lunch, a bell is rung and then we talk. Lunch is the time we’re all together and can share.

Then there’s a break for about an hour, during which some people do the lunch clean up. Then offering service again for 1.5 to 2 hours, and then study time. Then medicine meal: a few people eat, many don’t. It’s also time when people can talk. That’s only an hour, including cleaning. Then evening meditation and it’s free time until you go to sleep. Some teachings are in the morning from 10 am to 12 pm. In that case then there isn’t the afternoon study time that day. Other times teachings are in the evening. We stream as many teachings as possible. People appreciate that.

Audience: Who chooses who does what?

VTC: Oh! [laughing] I stay out of that because the people who organize it like rotas. Did anybody ever count up how many rotas there are? There’s a rota for who sets up the water bowls, who takes down the water bowls, who makes the offering on the altar, who removes the offering. There’s a gazillion rotas. I would not organize it this way. But a leader has to know when to step back, and they like rotas.

We’re close to two bhikshuni monasteries in Taiwan. At them, each nun is assigned a job, most for 6 months or a year, and they do that job consistently during that time. This applies to jobs everyone can and should learn, for example, helping in the kitchen, setting up the altar and making offerings, running errands for the community. Jobs that require particular skills, for example, bookkeeping and accounting, are not changed like that. To me, that is more efficient than writing so many rotas.

Sravasti Abbey nun: We do have departments. We grew to a size where we had to organize departments. There are people with certain expertise who’ve held a position for a long time. For example, Venerable Semkye has forestry experience, so she does the forest.

VTC: During their study time once in a while someone will choose to work in the garden instead. That’s fine. In the summer we will change the schedule, because it’s really hot. Then we do the garden in the evening and study earlier.

Sravasti Abbey nun: I just wanted to add that we have an anagarika class that I thought was really helpful. When I joined the Abbey I was nun number ten. So, there was maybe only one person in training at a time for a while. Now there’s a group of anagarikas. So starting a few years ago, the nun who is a therapist and another senior nun started to meet the new trainees once a week for about an hour. I went to observe what they do and think it’s very helpful. First they do a check-in on everyone’s experience. This year, the class was initially afraid and so didn’t speak so much. So we created a space where they could talk about what they were afraid of. You could see the relief.

Some people cry, they’re so relieved when we tell them they don’t have to be perfect. Listening to others, they relax and say, “Oh, we’re all going through the same thing.” It takes out a lot of the competition. Once the new anagarikas start to meet every week in a group like that, slowly that group builds trust. It’s very nice to observe how that group has grown over the last two years. A good deal of the anxiety and difficulties that come up in the new people is resolved in that group. At least people understand that they aren’t alone.

Recently in that class, they’ve been going through the Abbey policy guidelines very slowly. First they learn the anagarika precepts, then the guidelines for the Abbey. They read a small section and then discuss, “Why do we have this guideline? How does it help your practice?” The group is focused on practice.

So if people talk about difficulties they’re having with other people, it’s about how they’re angry and how they’re working with their anger. The issue isn’t “So and so did this.” It’s about what’s happening in your mind. People talk personally about what’s happening in their practice and how they’re working with afflictions that come up while offering service builds an open culture in that group, which is very healthy.

VTC: You’re in that group now. Would you like to talk about it?

Sravasti Abbey male trainee: Yes, really helpful. All the unsaid stuff that we’re not sharing at the very beginning comes out and there’s space to resolve it. There was something going on between my roommate and me, but we never spoke about it. Then suddenly one day we just started opening up about competitiveness and this kind of stuff. Both of us were very relieved after we discussed it. A lot of relief came from that. It was very beautiful.

Then instead of having some kind of tension, or trying to be perfect disciples and watching our stress build up—we help each other. That really settles things down. Sharing in a group that’s formed so that people can open up and learn from one another: a good entryway into the community. You have one foot in the community, one foot still outside, but you’re slowly getting in more and more.

VTC: The group is men and women together, which I think helps to break the ice a bit.

Audience: Do they also have a mentor from the beginning?

VTC: Yes. Sometimes people switch mentors. Sometimes the mentor and the mentee aren’t the right fit.

Audience: But there is a mentor after ordination?

VTC: Oh yes. For sure.

Audience: I was just wondering, because now we’re talking about a community that has been founded from the beginning with these kinds of guidelines. But we are in a community that has existed for 40 years. Would you have any advice or ideas about how to slowly form a community? [laughter]

VTC: Having discussion like I mentioned before where someone prepares questions about how you’re understanding and practicing the Dharma while people meditate and then groups of 5 or 6 people discuss the questions—this would be one way. That seems like it would be the easiest way but you’ll meet some pushback from people who don’t know how to share what’s going on inside or don’t feel comfortable doing that. How old are the people who have been at your monastery a long time?

Audience: I think that some of the older monks have over there 20 years.

VTC: I don’t know any of the younger ones. In that case, start slowly. Maybe start with offering the Nonviolent Communication course and encouraging people to come. If there’s already a community culture built up over decades, you’ll have to encourage people. You can’t tell them or require them to learn NVC.

You could do something like our anagarika class for the novice monks. One of our male anagraikas just took novice (sramanera) ordination. He said, “I’m going to miss the anagarika class!” So my guess is he’ll keep going to the group.

So start with the juniors. Use the way of leading a discussion group that I described earlier. When we do those discussions, five or six people form a group. When there’s 15 or more people, the group is too big for everyone to have enough time to share.

Audience: And how often do you do these groups?

VTC: Some of the discussion groups are combined with the courses and retreats that we lead. Sometimes somebody will suggest a topic so we’ll have an impromptu discussion. The anagarika class is every week. Starting something weekly like that, especially for the juniors, is really good. Then the seniors say, “What are you guys doing? What are you talking about?” And you’ll draw them in too.

Sravasti Abbey Nun: For a while, we had weekly Vinaya discussions. During winter retreat one year, Venerable Chodron was not teaching a weekly Vinaya class so we read a text together. We had a short reading and would get together and discuss it. That was very helpful to keep up this kind of Vinaya-based discussion.

VTC: Another example is we could play the recording of the conversation we’re having now during a Vinaya course, and then somebody will write the questions and lead the meditation. Then we’ll break into groups and discuss it.

Audience: For the winter, three-month retreat, what kind of retreats do you do?

VTC: The three-month retreat this year is on the four establishments of mindfulness. I think this topic is very important. People get into tantra too quickly. Before you even are aware of your present body and mind—their causes, nature, functions, and results—you’re taught to visualize yourself having a deity’s body. You have only a very fuzzy idea of emptiness, which is a crucial meditation that is a prerequisite to entering tantra and engaging tantric meditation properly; you haven’t thought much about the disadvantages of samsara, and think bodhicitta means just being nice to people, but you’re already visualizing yourself sending out light that enlightens all sentient beings. This isn’t how the tantric texts themselves say to approach tantra.

The four establishments of mindfulness is very good for putting people’s feet on the ground instead of people craving to hear about light, love, and bliss. In many previous years, the main meditation for winter retreat has been the practice of a kriya tantra deity combined with the lamrim.

Purification practice is also important for everyone to do. All the morning sessions, and usually evening sessions too, start with prostrations to the 35 Buddhas. Some people at the Abbey have taken highest class tantra empowerment. They have daily commitments and retreat commitments, so they may do their winter retreat together in another room.

Audience: Usually during these three months, the whole community is engaged in the retreat?

VTC: Yes, but like I said, there are two groups. The group that’s doing strict retreat still washes dishes. But they spend the rest of the day in meditation sessions or studying. They get some exercise too, often in the form of shoveling snow or taking a walk in the forest with snowshoes. Meanwhile, the second group attends half the meditation sessions, studies, and offers service to keep the monastery running.

Audience: I have another question. One is personal, and the other one is more general. You are someone who is in charge of a nunnery. Personally for you, what is the most challenging thing?

VTC: For me?

Audience: Yes, for you.

VTC: My own mind. My mind is the most challenging thing. It’s an incredible opportunity to learn, because you’ve studied the three kinds of generosity, the three (or four) types of ethical conduct; you know the antidotes that Shantideva taught, as well as the lists of mental factors, categories of duhkha, and so on. But when you’re in a position of responsibility, such as being an abbess or abbot or resident teacher, you have to practice it. Really practice it, because people come to you with all sorts of needs, ideas, problems, and aspirations. So you have to have some sensitivity to what and how they’re thinking and how to help them. In addition, when you’re in the position of responsibility, the buck stops with you. If you say okay to something that isn’t okay and it goes flat, then you’re in charge. You accept responsibility and do your best to fix it. Also, the person who is in a position of responsibility gets criticized a lot. Or people are mad at you because they think you said something you didn’t say. So you have to grow up and learn to see the people who are criticizing you as suffering sentient beings and cultivate compassion for them. But you also have to admit your own mistakes and foibles. Dealing with our own minds in all these situations is challenging.

To always be able to deal with my own mind and to remember that my job right now is to help this person in the Dharma, that’s my job. If I’m offended by something they said or did, that is my problem. I have to deal with it. But I have to help this person, whoever is coming to me right now.

Audience: And my last question, I promise.

VTC: You can ask as many questions as you like, it’s okay.

Audience: What do you think is the most successful aspect of the Abbey?

VTC: Successful? About the Abbey? I’ve never even thought about that. I don’t know, what do you think?

Sravasti Abbey male trainee: Transparency brought me to the Abbey. People are not pretending to be better than they are. They’re just really transparent about where they are in their practice, what they’re trying to accomplish, what they’re going through. This kind of transparency is really beautiful.

Also the way the people hold their precepts and the Vinaya. The posada, we do a lay “posada” as anagarikas and lay guests. We have a short ceremony. Before that, the anagarikas confess to the bhikshunis or bhikshus. I find this really powerful. It makes me trust the community very much.

Audience: But you have a level of transparency, there has to be a lot of trust.

Sravasti Abbey male trainee: It takes time. This is why we have the anagarika class and our discussions, and slowly people open up.

Audience: That trust and openness can only be created with good communication, right?

VTC: Yes. What would you say?

Sravasti Abbey nun: We have a healthy functioning community. I’ve learned a lot about compassion just through living together with other people—what it really means to hold someone through their practice and to have people hold me with their practice for years and years. We watch people go up and down. But as a community, we have the strength to hold people when that happens. That’s been very inspiring for me.

When people are in a dark place or stuck in their practice and you’re living together, it strengthens my faith in the Dharma to see how the community comes together to help. Everybody is practicing. There’s only so much we can discuss and in the end we both have to work with our minds. Then as we live together, it works out. People come and a few go, and we can hold that too as a community.

I’ve watched the community mature over the years. I came at year 10 and now 10 years have passed. I got to see the generation that helped to start the monastery and how they matured. I’ve watched them and the Abbey grow organically, with everyone always coming back to the Dharma and the Vinaya. Maybe that’s the biggest success, I think. No matter what, it’s not about who specifically is there. I don’t know how to say it, but no matter what, we always come back to the Vinaya.

For example, how do we organize our departments? How do we organize our kitchen? What does the Vinaya say? That’s why we’re not a for-profit enterprise. We’re not a corporate entity, trying to make money. We come back to the Vinaya for guidance.

VTC: Vinaya isn’t just a bunch of rules; there’s a lot of practical wisdom and compassion in it. We’re not strict and inflexible regarding Vinaya. We discuss, “Okay, this precept was made in a context that fit in ancient India, but maybe the context now is different, so the literal meaning of the precept doesn’t fit our society.” You have to study the origin stories for the precepts—what was the affliction that the Buddha was pointing out that made him set down this specific precept? What physical and verbal behavior was he restricting? Why? What was he encouraging in its stead? We’ll talk about that affliction, and how it relates to us nowadays in the society we live in.

Audience: Very interesting.

VTC: Yes. Vinaya and posadha become something alive for us.

Audience: Relevant, really relevant to each individual involved.

VTC: Yes.

Audience: Can I ask a cheeky question? How, especially for both of you, how do you feel when Venerable Chodron is not there? Does it change the energy of the environment? Do you feel that the Abbey continues everything or is there any difference? Because I hear so much about her personal input and practice as well, and this is very inspiring. How does it work when she’s not there?

VTC: Everyone goes wild! I want to go to the movies. Where’s the chocolate? [laughing]

Sravasti Abbey nun: Venerable used to travel at least twice a year. When she’s away, it’s a time where people have to step up and figure out how to keep the monastery running. In the early days people would say, “Help!” And she’s replied, “I’m traveling and I’m teaching. Figure it out yourself.” So you grow up. Now there’s enough seniority in the community to hold things together.

But even ten years ago when I joined, the community continued to function well when she was gone. Venerable emphasizes all the time that the monastery can’t be about her. It’s about what we do together; it’s about building a sangha. Of course, we’ve had discussions about how to hold the space. We had some recently after we listened to her talks to sangha members in other groups about how to establish community. We talked about what happens when the teacher dies. How do we make sure the sangha continues to run as it should? We’ve had those discussions, and they’re very frank.

Audience: So you’re discussing when Venerable Chodron passes away?

Sravasti Abbey nun: She’s been planning for that the whole time.

VTC: Yes. I talk about it because the Abbey can’t depend on one person for its continuity. It can’t depend on one person to make it grow. The Abbey won’t survive if people donate because one person is there. We want them to believe in the sangha and see the existence of the sangha as important for the existence of the Dharma.

Sravasti Abbey nun: A lot of that comes from doing the posadha (sojong) every two weeks. I’ll give an example. Once, there was a conflict in the community and someone didn’t want to come to posadha, but you can’t not come—Vinaya says that everyone who is healthy and who isn’t doing special work for the sangha must attend posadha. So someone went to get the person who didn’t want to come. I was very junior at the time. I saw the seniors go and tell them, you have to come, otherwise we can’t do posadha because everyone in the territory (sima) must come. So that person came, and the community worked out the issue at posadha.

Audience: Wow.

Sravasti Abbey nun: Yeah, their mind moved. Otherwise that person was going to hide in their room. So as a junior I saw that and thought, “Wow, that’s the power of the sangha structure the Buddha set up.” Now, in addition to posadha, we do the varsa (rainy season retreat) and the invitation for feedback (pravarana) at the end of varsa. We do kathina and the novice ordinations. All that has really helped the community to grow.

VTC: There’s real power in these Vinaya ceremonies and we do them in English. That makes a huge difference because you understand what you’re saying and what you’re doing. We’ll have a teaching about each of the ceremonies for people who haven’t done them before so people know what’s going on, why the Buddha set this up the way he did. There’s real power in these ceremonies. You’re doing something that the sangha has been doing for 2,500 years. You’re grateful to all the generations of monastics that came before you, and you know that it’s your responsibility to contribute to sustaining it for future generations.

Audience: Can I ask about the finances?

VTC: Okay.

Audience: If I can say, you were very bold when you decided to start the Abbey.

VTC: It was totally crazy. Totally nuts.

Audience: When you said that nobody has to pay to live here or to attend courses and retreats, how do you cover all your expenses—property taxes, electricity bills, petrol, and so forth?

VTC: We rely completely on donations. We call it an economy of generosity. An economy of generosity entails educating the lay people, telling them that we want to be able to give the Dharma freely, and we hope that people value what we do and will support us so we can continue to do that. In other words, teaching the Dharma is not a business; it is open without charge to everyone. That is how the Buddha taught. Similarly, staying at the Abbey is not like staying at a hotel where you’re a customer that pays for a service. We explain that we want to live a life of generosity and we want other people to do that as well.

At the beginning, people just let us know they were coming for a course. But people were canceling at the last minute and their place would go empty so we started to ask guests to give $100 dana (offering) to reserve their place. We tell them that we’ll return that money when they get here, unless they want the Abbey to keep it. So we found that that kept people on track and decreased last minute cancellations.

We also don’t use the word “fundraising.” We call it “inviting generosity.” Our philosophy is that people should give because they want to, because they believe in what we’re doing. We don’t want people to give because if they give a certain amount they’ll get a Buddhist statue that’s this big; if you give twice that much you get a Buddhist statue that’s twice as big. If you give five thousand dollars then you get to have lunch with the abbess, and if you give 10 thousand, the abbess will give you her mala. Nothing like that.

We recite the names of the people who have given in the last two weeks twice a month when we do tsog. But we don’t name rooms after people or put up lists of donors with how much they gave. We don’t do all this kind of stuff. No.

Audience: It’s been working fine so far.

VTC: We don’t have all the money for the Buddha Hall. We need just a mere two and a half million more. Actually, when we include all the things, maybe three million. But we’re hopeful. We’re constructing the Buddha Hall for sentient beings. If they want it, they’ll donate and it will be constructed. If they don’t want it, they won’t donate, in which case there’s no need to build it.

We had a debate regarding if we should try to take out a loan. At the beginning when we purchased the land, we couldn’t take out a loan. Banks don’t like to loan to religious organizations because it’s embarrassing for them to foreclose on a temple or church. Personally, I don’t feel good about taking out a bank loan and paying the interest with donors’ money. But it looks like we may have to.

I have my own unique ways to see inviting generosity, that not everyone agrees with. For example, Abbey friends in Singapore wanted to help us by fund raising the usual the way they do in Singapore. Each brick of the building costs $100. If you give the amount for one brick, you get to write your name on a brick that will be used in the temple. I vetoed that. It’s playing on people’s attachment to ego and I don’t want to participate in doing that. I feel strongly that when people donate to the Abbey, they do it because they believe in the value of what we’re doing and they want other people to benefit from the Dharma too. I want them to have a genuine heart of generosity. If you’re giving to get something like a Buddha statue or your name being displayed publicly, it’s not pure generosity.

Similarly, if we as sangha members give little prizes, donor rewards, and things like that, then we’re not coming from a mind of generosity. We’re giving a small gift to get a bigger one—that’s a form of wrong livelihood explained in the lamrim. The Buddha set up the interaction of the sangha and lay followers as a system of mutual generosity. I find that so beautiful. And inspiring too.

Audience: And the food was the same?

VTC: Regarding food, from the very beginning, I said, “We’re not buying food.” We can’t do it exactly the way the Buddha did before because we live in a rural area in the middle of nowhere. Plus asking people to cook food and bring it to us every day is too inconvenient for them—they work and can’t take off time to drive up to the Abbey. Also, most of our supporters are not super rich and cannot always buy food to feed 25 or 30 people. So when people come to stay with us, we request them to bring groceries. The local lay followers have organized a system whereby people from all over the world can send money for groceries, and they’ll buy the groceries and bring them to the Abbey. They are so kind—they bring food every week in the snow, in the hail, in the summer heat. The lay people will call us once a week and say, “We want to offer. What do you need?” Then we’ll tell them, and then they’ll use whatever funds they have to buy the groceries.

When I first started to live at the Abbey, we said, “We’re not buying food.” People said, “You’ll starve. No one will offer food.” But we haven’t starved yet and it’s been 20 years.

When I said that we’re not going to buy food, people said, “You’re going to starve.” I said, “Let’s try.” We live in a very non-Buddhist area. It’s a very redneck area. When people come to stay with us then, they usually offer some food when they come. At the very beginning, there were only a handful of Buddhists who brought food. Then someone from the Spokane newspaper came to interview us. We talked about just eating the food that is offered to us, and told them about Buddhism and the Abbey program—we introduced the Abbey to the local community.

The interview was published in the Sunday paper. The next day, or two or three days after that, somebody drove up to the Abbey with an SUV full of food. We don’t know her. She’d never been here before, she’s not a Buddhist, but she read the article in the paper and wanted to offer. We were flabbergasted. This is the kind of thing where you can bring out people’s generosity. They feel so good giving. When everything is about charging then it’s just business and no one creates merit.