Seniority in the sangha

The story of a new nun who found benefit in the seniority system

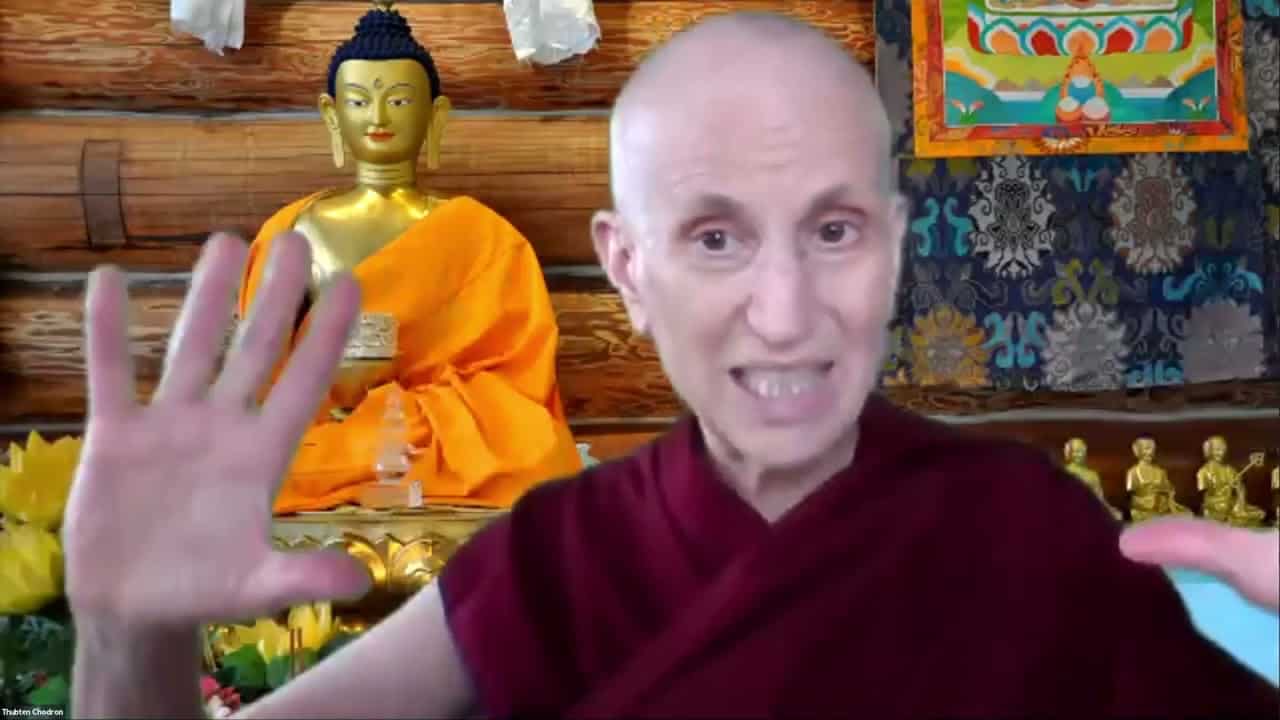

Venerable Thubten Pende is a fully ordained nun at Sravasti Abbey. She received novice ordination in her home country of Vietnam and, after coming to the US, joined Sravasti Abbey.

Today I would like to share my reflections about seniority in the sangha—what it means to me at the gross level, why misconceiving the meaning and notion of seniority caused me so much mental suffering in my early monastic life, and how understanding seniority has had a transformative effect on my personal growth and spiritual practice over the last one and a half years.

Like any workplace, organization, or institution, a monastery adopts a seniority system—a ranking or hierarchy among monastics based on the relative length of their full or novice ordination. At the gross and individual level, seniority refers to a position or status that a monastic holds relative to other monastics. Much to my surprise, my naive thought when I ordained was that my seniority in the ordination order would make me feel special and important. I had no idea what it entailed for a few years. Indeed, seniority does have several positive factors. First, it provides monastics a clear understanding of why certain roles, duties, and responsibilities are designated to seniors such as novice mentors, novice master, guides, and so on and what to expect from people in those roles. Second, it is used to assign monastics to specific tasks or responsibilities or to different roles in formal events based on their seniority. Finally, it makes it easy for people who are in charge of setting up for teachings, rituals, and formal events to know where to seat monastics properly.

But first, I would like to share my past personal experiences with you. By now most of you already know that I was trained in a nunnery of about 150 nuns in Vietnam for about six months after I ordained. As a “baby” nun in that nunnery, I felt left out because I was the last one in the long food line or in the last row during chanting and during confession ceremonies. I did not feel at ease sitting in the middle section of the big dining hall reserved for nuns with at least 20 years of seniority, when there were no seats available for the most junior nuns like myself when I showed up late for lunch. I didn’t feel that I belonged to that group at all.

Then a few months later, a group of 10 young lay women went forth and ordained. I was a little arrogant because I was more “senior” than them, especially I was no longer the last one in the long food line. But my misery about seniority continued when I went to Taiwan for full ordination in 2017. I remember feeling irritated and resentful over the seniority issue for quite a while. All sorts of negative thoughts kept popping up in my mind: who came up with the rule that allows the junior monks to stand or sit in front of the senior nuns? The Buddha or the ancient masters? Why do the nuns have to walk behind the monks? It was unfair that all the junior monks became senior to me overnight because they did not have to go through the dual sangha to receive full ordination. Fortunately, I was able to let go of my nagging complaints and rumination over that issue because I had to finally accept the philosophy, “when in Rome, do as the Romans do.” I had a great laugh at myself when recalling my initial motivation—I came to Taiwan to receive training for full ordination and not to protest over the seniority or gender inequality issue.

You might wonder why I struggled against the meaning and notion of seniority in my early monastic life, a struggle that triggered anger, jealousy, pride, competition, arrogance, irritation, and resentment. Let’s examine, explore, and investigate what the real troublemaker is. Indeed, what I call “seniority” is merely a convention. When I ordained, I was told my seniority or position in the ordination order. After being in that position for a while, I started to think that my seniority of “most junior,” “newly ordained,” “novice,” “training nun,” and eventually “bhiksuni” actually existed. Furthermore, I identified with my seniority and all that pertained to it—status, privilege, authority, title, role, and responsibility—as something I possessed or something that was actually who I am: I am more senior than you, I am behind this monk, I am ahead of this nun, I am a chant leader, I am a Pratimoksa reciter, this spot is mine, I am number 11 in the ordination order, and so on. Upon very close examination and reflective investigation, I realize that seniority is not who and what I am. Indeed, the sense of self and self-obsession are the real troublemakers. Because I was unable to recognize this perception of self, I kept wrapping myself up in that feeling or perception of self, giving weight to it, believing in it, and worst of all, buying into the I-making, my-making habit. As a result, I carried a useless burden due to my increased attachment to my seniority along with an unrealistic expectation about its fixed and unchanging nature. I completely ignored the fact that I might move up or down in the ordination order in different situations at any time. I am very happy that my mental misery related to the seniority issue has gradually becomes less troublesome over the years.

Last but not least, I would like to share how seniority has had a positive and transformative effect on me over the last one and a half years. Seniority has helped me develop a sense of respect for the seniors, seek guidance and advice from them when needed, and learn from their examples, knowledge and expertise, their skills, and their personal experiences. In addition, I feel the need and responsibility to take the initiative to explore suitable opportunities to learn more skills so that I can step up to many roles that a senior holds. Furthermore, it has also helped me overcome my shyness and passivity and become more engaged in more activities such as leading chanting or participating in discussion groups. Spiritually, each time I move up in the ordination order after a new nun is ordained, it is a perfect time for me to perform a self-evaluation by examining and asking myself: do I climb up the staircase to liberation or do I climb up the monastic career ladder? Am I a role model and a good example for the juniors? Are my virtues and good qualities growing? Am I becoming more stable, steady, and grounded in the Dharma? Am I getting a little more mature in my practices? These questions help me reflect back on my practice so that I can take firm and decisive steps to stay on track and to progress on the path.

Even though I have been ordained for a few years, I still consider myself a “baby” nun with so much to learn, to improve, and to grow. I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere and heartfelt gratitude to Venerable Chodron, Venerable Khadro, and all the seniors who have lifted me up with their unending kindness and support.

Venerable Thubten Pende

Ven. Thubten Pende was born in Hue, the Imperial city of Vietnam, in 1963. She visited Sravasti Abbey for a short time in June, 2016, and returned in September for a three-month stay. She was interested in further exploring how a traditional monastic setting could be adapted to present American culture, as well as how Dharma practice and teaching are explained in a Western context at the Abbey. After her first month at the Abbey, Ven. Pende extended her stay to include a three-month winter retreat. Just before the winter retreat began, she asked to join the community. She is deeply honored that Venerable Thubten Chodron accepted her request and gave her a new lineage name, Thubten Pende, on Chinese Lunar New Year, January 28, 2017. She received full ordination in Taiwan in 2017. She was a resident at Sravasti Abbey until 2024.